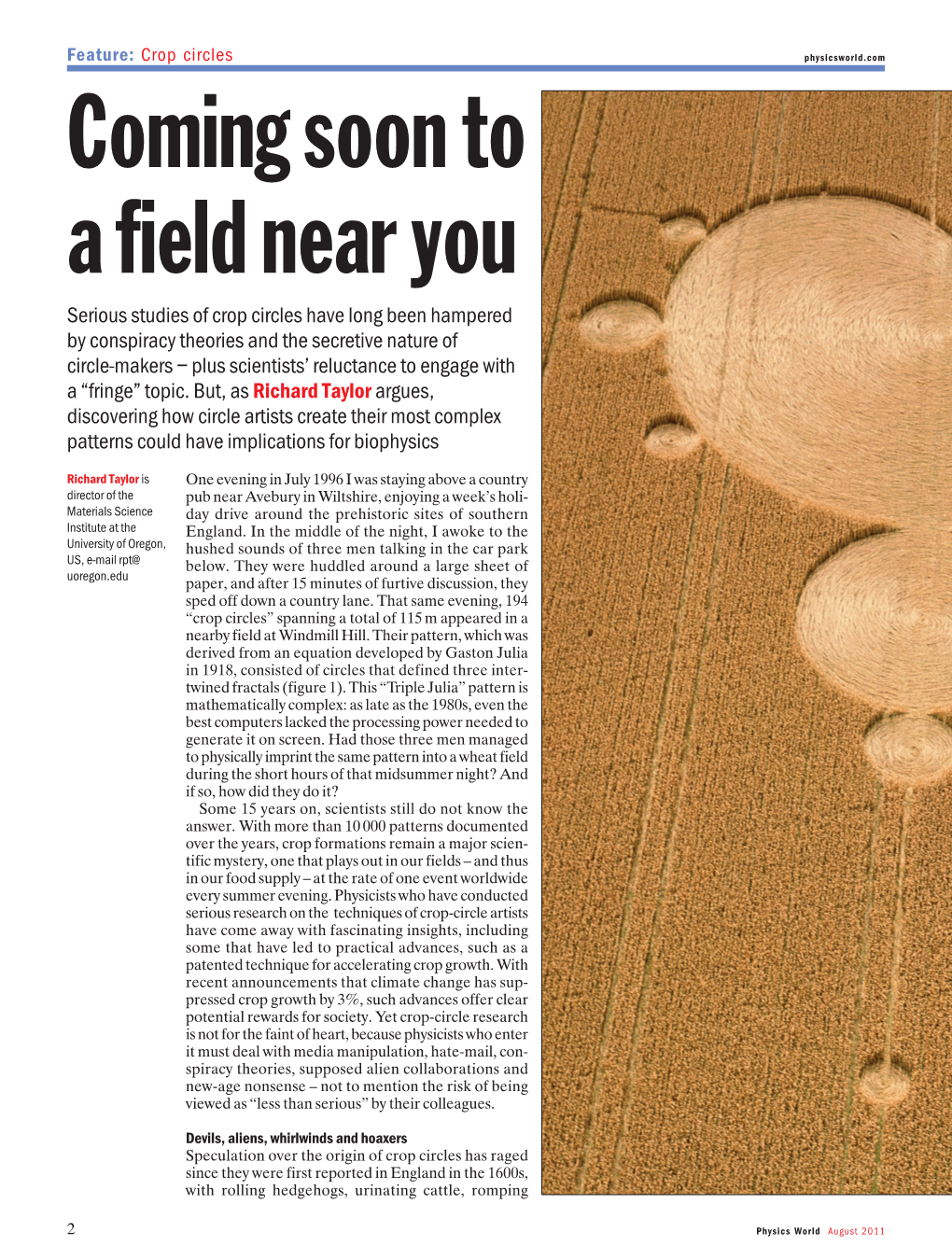

Coming Soon to a Field Near

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

So Now I²ll Count from Ìve to One and Bring You out of This

Media. Memory. Meme. Colin Bennett. Prime Time. ! !" #" $" #" %" &" '" ( =5#'5/# ">00# .56')# !"#$%#&'#$#($)*+(# ,+-+(+#.(&,&,#/&)*# )*+#$0&+',1#"#/&00# 8(5%# 2+#)$03&'4#)5#)*+%# )5'&4*)#$256)#%7# 86)6(+#$'9#/*$)# ?-+#)5# )*+7#/&00#5(#/&00# '5)#95#)5#%+1: 5'+# ;$-&9#<$.52, $'9# 2(&'4# 756# 56)#58# )*&,1 ")*("+,-(#."+/ 0!!#"1++-2 !"#$$%&'()*+ Vol. 24 No. 1 Issue # 154 !"#"$%&'()*+(,-./01** UFO Volume 24 • Number 1 columnists 6 Publisher’s Note: William J. Birnes 7 Saucers, Slips & Cigarettes: Dierdre O’Lavery 8 Rocket Scientist: Stanton T. Friedman 10 Outside the Box: Mike Good 12 Opinionated Oregonian: George W. Earley 14 Alien in the Attic: Farah Yurdözü 16 Coast to Coast AM: George Noory 17 An Alien View: Alfred Lehmberg 18 The Randle Report: Kevin D. Randle 20 21st Century News: Dr. Bob & Zohara Hieronimus 22 Truthseeking: Dennis Balthaser 24 Inner Space: Sri Ram Kaa and Kira Raa 26 View From A Brit: Nick Redfern 27 Bryant’s UFO View: Larry W. Bryant 28 The Orange Orb: Regan Lee 29 Beyond the Dial: Lesley Gunter 30 Mirror Images: Micah A. Hanks bits & bobs 32 Arlan’s Arcanae: Arlan Andrews, Sr. Say hello to Dierdre! She is a 74 Rick’s UFO Picks: Rick Troppman new columnist, she is on page 7, and she is sassy. To Alfred Lehmberg: A belated thank you for the great cover artwork of Richard toon Dolan in Issue #153. Thanks also must go to our 63 Bradley Peterson very very very patient readers. This issue has been a long time coming. Next one should be just a bit more prompt. UFO Issue 154 features 34 Aliens vs. -

The Ancient Aliens Guy, His Hair, and Extraterrestrial Imperialism

The Ancient Aliens Guy, His Hair, and Extraterrestrial Imperialism Proposal by Stephen Few, English 102 At some point during the past few years, you may have tuned into The History Channel in hopes of seeing Pawn Stars or a new documentary. Instead of finding what you were looking for, you may have come across a show called Ancient Aliens. When watching Ancient Aliens, it becomes evident very quickly that the show is trying to convince viewers that extraterrestrials have visited Earth in the past. It is obvious that many people begin watching the show for a good laugh once they realize this, because the show is continually made fun of on the Internet and in pop culture. Some people don’t watch long enough because Giorgio Tsoukalos and his crazy hair make the show appear silly and incredible. The odd thing is that some of the ideas are logically possible. The Ancient Astronaut Theory, for example, is a very interesting explanation to many historical mysteries, though it is not taken seriously as a scientific theory. Tsoukalos and his team’s theories on aliens visiting Earth in the past are theoretically possible, so we should consider the implications if their theory is true. What effects will alien visitors have on environmental issues, world religion and cultures, and political organizations around the world in the future? What kind of preparations need to be made by the world in order to prepare for the next alien visitation? Giorgio A. Tsoukalos doesn’t have the college credentials of a world-famous archeologist; as a matter of fact, his body building hobby and sports medicine degree are far from archeology. -

To Believe Or Not to Believe the Crop Circle Phenomenon in the Netherlands Õ.Ì

To believe or not to believe The crop circle phenomenon in The Netherlands õ.ì Th eo Meder är iE ËiE In ¡hc Summe¡ of 2001, I srarted my rcserrch find ley lines rvith their clowsing rods or rneas- of n¿r¡atives colrcerning crop circles ancl their ure the energy with cheir pendulums, some possibly supenutural, clivine, ecologic,rl or come to meditate. l'atmers are sclclom pleased extraterrescrial origin. I wâ[ted to focus ol-r with clop circlcs because of the h¡rves¡ loss rh( râlcs Jnd c,rnrcptions ìrt u lrich clop cir- involved - c¿usecl not only by thc fìattening cles ale interpretcd ¡s non-rr¡n-macle signs of of the crop, but also by the trampling of curi- <(9 the time"^. Furthermore, rny ¡escr¡ch involved ous visito¡s. Sceptic scientists hardly bother to oq the concemporary cult movement ¡hat sc¿r¡tccl con-re, buc csoteric ¡ese¡rchers come to rnves- 9+{ with ufos in ¡he 1950s as a kincl of'proto- tigate, measure, sample, film and photograph, New ;\ge rnovernent'. 1 Crop circles u'e thc for later analysis rnd interpretation. Journalìsts 5i most tangible element of this mode¡n New r isir ¡he lormltion" cìuring rhc silly scrsc'n in Agc convicrion, which eìso incorporatcs ufo sealch of a juicy stor¡ preferably on the mys- sightings, alien rbductions, cattle mutilation, tery of the unexplaincd, on the subject of licde govcrûment cover-ups, free energy, lcy Iines, grecn mqn. or un thË l¡ct thct thc cntire cr,'p mysterious orbs of light, alte¡native ¡heories on circle phenonenon is a huge man-macle ¡rracci ¡hc c¡e¿tion of man, conneccior-rs with ancient cal jokc.2 ancl prehistoric Íronuments (like tÌre Ììgyptian pymnids ¿nd Cel¡ic Stonehcngc), thc cosmìc Englancl: where the knowledge of lost civilizations (Adar.rtis, ìVlayas phenomenon stârted a likc othe¡- etc.), and the expectations of rhe coming of Although some people to believe I new crâ or cven ¡n Encl of l)ays. -

Mufon UFO Journal Official Publication of the Mutual UFO Network Since 1967 Number 295 November 1992 $3.00

Mufon UFO Journal Official Publication of the Mutual UFO Network Since 1967 Number 295 November 1992 $3.00 Confessions of a Crop Circle Spy Connecting by Computer ... An Open Letter to the United Nations ... Current Cases Book Reviews & More Mufon UFO Journal November 1992 Number 295 CONTENTS UFOLOGY: THE EMERGENCE OF A NEW SCIENCE Walter Andrus 3 CONFESSIONS OF A CROP CIRCLE SPY! James Schnabel 4 CONNECTING BY COMPUTER John Komar & Pete Theer 9 CONFLICT OR COLLABORATION? Fred Whiting 12 OPEN LETTER: UNITED NATIONS 14 THE UFO PRESS Dennis Stacy 15 NEW'N'VffiWS 17 NEW DEPUTY DIRECTOR, INVESTIGATIONS 18 CURRENT CASE LOG Robert Gribble 19 READERS' CLASSIFIEDS 19 OPEN LETTER TO UFO INVESTIGATORS J. Howard, J.D. 20 LETTERS Robert M. Bailey 21 THE DECEMBER NIGHT SKY Walter N. Webb 22 DIRECTOR'S MESSAGE Walter Andrus 24 COVER ARTWORK Vince Johnson SSSm*B«*S*S*SS8f^^ § EDITOR Copyright 1992 by the Mutual UFO Network. Dennis W. Stacy All Rights Reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form without the written permission ASSOCIATE EDITOR of the Copyright Owners. Permission is hereby granted to quote up to 200 words of any one article, provided the author is credited, and the statement, "Copyright 1992 by the Mutual Walter H. Andrus, Jr. UFO Network, 103 Oldtowne Rd., Seguin, Texas 78155," is included. COLUMNIST The contents of the MUFON UFO Journal are determined by the editors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Mutual UFO Network. Walter N. Webb The Mutual UFO Network, Inc. is exempt from Federal Income Tax under Section 501 (c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code. -

The Welsh Triangle 35 Charles J Hall

A BRAND NEW MAGAZINE ON UFOLOGY & ALTERNATIVE THINKING TOP 10 UFOLOGY MOMENTS Lazar, Arnold & Rendlesham ISSUE #1 NOV/DEC 2017 NICK POPE THE From civil servant to the WELSH MoD’s UFO investigator TO THE STARS TRIANGLE Rockstar Tom Delonge Celebrating the 40th is shaping our future Anniversary of the Pembrokeshire sightings DYATLOV PASS SNOW WHITE The mystery deaths of Does the beloved princess nine Russian hikers in 1959 have Egyptian origins? THE PIRI REIS MAP ENIGMA Could this medieval map really show an ice-free Antarctica? MICHAEL CREMO Why human origins may go back further than we thought S-4 DIGITAL PRESS Plus more great interviews and features inside! EDITOR’S LETTER WELCOME! “Something inside me has always been there… - then I was awake, and I need help.” he above quote was featured feeling your IQ drop in front of the in the trailer for the upcoming television and smartphone watching TStar Wars: The Last Jedi, mind numbing talk shows and the which finds our hero Rey searching endless plague of vacuous ‘reality’ for guidance in helping her make celebrities. And that’s what the sense of her recent ‘awakening’. title itself refers to, the dark hidden The line stuck in our minds as we corners of the subconscious that were compiling this very first issue recognises there is a vast amount of Shadows Of Your Mind magazine, of information hidden just out of and it seemed pretty apt as interest view. Our hope is that Shadows… in what were previously fringe topics will act as the catalyst that fires up is on the rise. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boli, John Working Paper Small planet in the vastness of space: Globalization and the proliferation of UFOs, aliens, and extraterrestrial threats to humanity WZB Discussion Paper, No. SP IV 2018-104 Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Boli, John (2018) : Small planet in the vastness of space: Globalization and the proliferation of UFOs, aliens, and extraterrestrial threats to humanity, WZB Discussion Paper, No. SP IV 2018-104, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/184650 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under -

Water Security – Opportunity for Development and Cooperation in the Aral Sea Area

PROCEEDINGS Water Security – Opportunity for Development and Cooperation in the Aral Sea Area A SIWI / RSAS / UNIFEM Seminar Stockholm, August 12, 2000 The seminar was organized by the Stockholm International Water Insitute (SIWI) in collaboration with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the United Nations Development Fund for Women SIWI Report 9 Published 2001 by Stockholm International Water Institute Sveavägen 59 SE-113 59 Stockholm Sweden Front cover: Quadrata HB Printed by Arkpressen ISBN 91-973359-8-3 ISSN 1404-2134 WATER SECURITY - OPPORTUNITY FOR DEVELOPMENT AND CO- OPERATION IN THE ARAL SEA AREA by Ulf Ehlin Introduction One of the most severe manmade environmental and ecological disasters of all time was created during the last decades of the 20th century due to the lack of consciousness regarding the consequences of the integrated effects of widespread deforestation and water withdrawal for large-scale irrigation. The increased water withdrawal for irrigation reduced the inflow of water from the Amu Darya and the Sur Darya rivers to the Aral Sea by 90% compared to mid- 20th century levels, and resulted in a large decrease in the water volume and surface area of the Aral Sea. Also, the water quality of both the in-flowing water and the Aral Sea itself has drastically changed. The altered land use and massive irrigation caused basin-wide soil and water salinization, desertification, poor quality drinking water and chronic health problems for the population. The aquatic ecosystem collapsed, destroying a fishery. The increasing environmental degradation and its effects on the living conditions and health for people in the region has been known for decades. -

Crop Circles: Windows of Perception Lucy Pringle the Following Text Is Based on a Lecture by Internationally Reviewed by Ellen R

forty-five.com / papers /144 Crop Circles: Windows of Perception Lucy Pringle The following text is based on a lecture by internationally Reviewed by Ellen R. Hartman renowned crop circle authority Lucy Pringle, delivered on October 28, 2015, at the Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Moderator: Ben Nicholson This series of three talks is by people who are working beyond the edge of design. The series is called Taboo Subjects, meaning subjects that are not really thought about very much within the design and the architecture and the arts community. This evening’s lecture is being given by Lucy Pringle. She was educated in England and France and Switzerland and is a member of the Center for Crop Circle Studies, and a pioneer researcher into the effects of electromagnetic fi e l d s o n l i v i n g s y s t e m s . T h i s i n c l u d e s t h e p h y s i o l o g i calnd psychological effects reported by people after visiting and being in the vicinity of a crop formation. She also studies animal behavior, remote effects, luminosities, mechanical failures and audio effects. Within our discipline of arts and design and architecture, these are things that we desire so much to have access to and yet know so little about. Lucy Pringle works with scientists from all over the world and was one of the speakers at the Institute of Science and Astrophysics in Sofia, Bulgaria. -

Ufos 21 Preliminary Concept Plan UFO Tourism 21 for the Embassy and Surroundings 11 Embassies for Extraterrestrials 22

An EMBASSY to Welcome an EXTRATERRESTRIAL CIVILIZATION to Earth The Most Lucrative Project of All Time awaits Your Decision ! 1 Executive Summary 4 The timeline & preliminary plan This can be your country ! 5 of actions 13 Benefits for the host country 6 Scientopolis: the world’s leading-edge scientific hub 14 1. Religious tourism, a major source of revenue 6 2. A unique and ambitious tourist opportunity! 6 Astronomical Evidence 15 The Embassy Project 8 Supporting Evidence 1. Construction of an embassy to welcome of Extraterrestrial Presence 16 an extraterrestrial civilization 8 1. Extraterrestrial evidence in ancient times 16 2. Specifications 8 2. UFO sightings today 17 3. Site plan 9 3. Crop circles 18 4. Architectural plan 9 4. Messages from extraterrestrials 19 5. Timing 9 Fast Facts 20 Preliminary site plan Public Opinion 20 for the embassy 10 Exoplanets 20 UFOs 21 Preliminary concept plan UFO Tourism 21 for the embassy and surroundings 11 Embassies for Extraterrestrials 22 Table of Contents Table Extraterrestrials require The promotor organization: special diplomatic status 12 The International Raëlian Movement 23 2 An Embassy For Extraterrestrials The Most Lucrative Project of All Time Awaits Your Decision ! 3 So, US astronaut L. Gordon Cooper Could your country benefit from Jr. (1927 – 2004), a veteran of both large amounts of additional revenue Executive Mercury and Gemini space missions, over the next decade? Could it use might have been ahead of his time the even greater sums that would when he said “ I believe that these accrue -

Nomor 10 INFO-UFO

Nomor 101 INFO-UFO INFO-UFO 2 Nomor 10 MAJALAH UFO INDONESIA ISSN : 1411-9676 Dari Redaksi Pada masa Perang Dunia II, ada sebuah fenomena aneh Penerbit: Yayasan INFO-UFO yang sering terlihat di angkasa. Mereka menyebutnya sebagai Pemimpin Redaksi Foo Fighter. Tak ada yang tahu Nur Agustinus pasti, milik siapakah benda terbang aneh tersebut. Baik pihak Sekutu maupun Jepang, keduanya sama- Staf Redaksi Leonardus T. sama menduga pesawat aneh itu adalah dari pihak lawan. Namun, dokumen dan analisa yang muncul belakangan menunjukkan dugaan bahwa pihak Jerman Sekretaris Redaksi di masa itu telah melakukan riset serta memproduki pesawat terbang berbentuk Maria Yuthi Anggraheni aneh, yang diduga kuat adalah Foo Fighter tersebut. Bagian Keuangan Tentu saja, hal ini membuat banyak pro dan kontra. Kalaupun seandainya Johana CR. Nazi Jerman sudah berhasil membuat piring terbang, mengapa mereka bisa kalah dalam perang tersebut? Ataukah riset mereka belum berhasil tuntas? Koresponden LN Atau, para ilmuwan yang dimiliki mereka keburu ditangkap atau membelot ke Endang Martina (USA) pihak sekutu? Ilustrator Pada tahun 1932, Adolf Hitler yang mengendalikan masyarakat Jerman Alfons Hendrata memaksa para ilmuwan untuk bekerja di Laboratorium untuk pengembangan rancangan-rancangan pesawat. Dibantu oleh teknologi pusaran air Viktor Bagian Umum Schauberger dan para ilmuwan ahli-ahli teknik seperti Schriever, Habermohl, Mochamad Sanusi Eko Kuswanto Ballenzo, dan Miethe, Jerman mulai menerbangkan pesawat pada awal tahun 1938. Terdapat juga beberapa bukti bahwa Jerman menemukan sebuah piring terbang alien yang terjatuh pada tahun 1837. Sebagai hasil dari seluruh teknologi Alamat Redaksi ini, usaha-usaha keilmuwan Jerman didorong semakin maju pesat, dan dilakukan Jl. Krembangan Barat 31-I pada beberapa fasilitas-fasilitas riset rahasia di Reinickendorf, Kummersdoef, Surabaya 60175, Indonesia Telp. -

Ufos and Popular Culture

UFOs and Popular Culture UFOs and Popular Culture An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Myth James R. Lewis B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by James R.Lewis All rights reserved.No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, James R. UFOs and popular culture : an encyclopedia of contemporary myth / James R.Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-265-7 (hard : alk.paper) 1. Unidentified flying objects. 2. Popular culture. I. Title. TL789 .L485 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-010925 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O.Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America H Contents h Foreword: UFOs—Folklore of the Space Age, Thomas E. Bullard, ix Introduction,xxvii List of Contributors, xxxix UFOs and Popular Culture: An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Myth Abductees, 1 Astral Projection (Out-of-Body Cape Canaveral Monsters, 59 Abraham, 4 Experience) and UFOs, 40 Captivity Tales and Abductions, 59 The Abyss, 4 Astrology, 41 Cargo Cults, 60 Adamski, George, 4 Atlantis, 42 Carr, Otis T., 63 Advertising, 6 Atmospheric Life-Forms, 44 The Cat from Outerspace, 63 Aetherius -

Images of the Mind and Images for the Eye

MIKAEL ROTHSTEIN Images of the Mind and Images for the Eye An Iconographical Approach to UFO-Mythology Introduction In the study of contemporary new religions and popular religious or meta- physical notions, the iconographical sources are often sadly overlooked. In this article it is the intention to present an iconographical approach to one single, although significantly versatile, aspect of modern, non-traditional mythology, namely the notion of "flying saucers" or UFOs (i.e. Unidentified Flying Objects). The actual UFO-religions may be insignificant in terms of adherence, but the very concept of UFOs holds a strong position in contemporary meta- physics and spirituality, as we find it in the so called New Age movement and elsewhere. Further, but often with no conscious religious or meta- physical aspects attached to it, the concept is known to almost every indi- vidual in modern society. This means that I shall consider the idea of "flying saucers" in very different contexts ranging from religious sects to contemporary folklore. The intention is to analyze some examples of how the notion of "flying saucers" or UFOs has been transformed into ico- nographical products. The examples, hopefully, demonstrate the extreme diversity of images and notions that have developed from the idea of the "flying saucers" within the last 40-50 years. Some Remarks on the Nature of Religious Imagery Religious texts, as well as narrations, are discursive. The message of the text or the narration is unfolded sequentially, one step followed by the next. Religious imagery displays its meaning in quite another way. The picture, sculpture or relief appears as a coherent, total manifestation of 270 MIKAEL ROTHSTEIN meaning, as the entire message is given simultaneously.