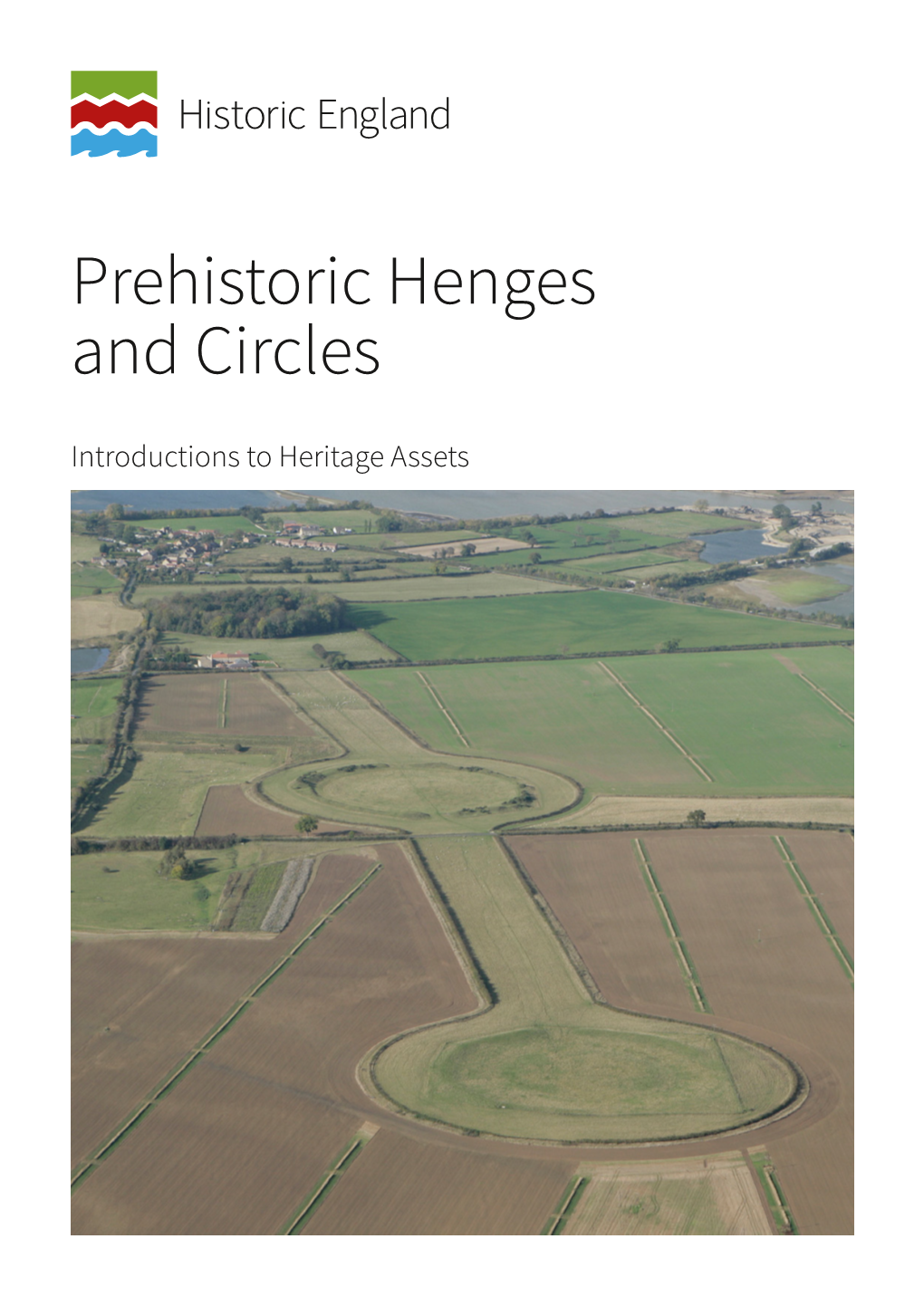

Prehistoric Henges and Circles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

November 2019

November 2019 Published by Fyfield, West Overton and East Kennett View from the Rectory Parochial Church Council for By the time you read this, one and young people. Our schools and the Upper Kennet Benefice way or another, the issue that has churches can be a place of balance dominated the news, parliament and and sanctuary for our children, who politics for over 3 years will be may be feeling upset and anxious. resolved and the future relationship The Mental Health Foundation has Please note the Upper Kennet between the UK and the wider excellent advice on talking to Benefice now has a new website world set on one particular course of children about scary world news. access link www.kennet8.org.uk action. Whatever our personal Think about the needs of political viewpoint, these changes particular groups in your area. A new email address for the Benefice will impact all of us, and are likely What are the local challenges for us Office: to have the greatest impact on the in the countryside? How are the [email protected] vulnerable, as new trading farmers and local business feeling? arrangements come into force. We Shop local, spend a few minutes have been given some indications of listening to those on the checkouts what to expect and there will be or at the markets. Kennet Valley Lottery Club more government guidance in due Have a Forward Together meal course - there might be a temptation or coffee morning - encouraging draw winners for some to ‘batten down the endless discussion about the rights £100 Number 47 Jeremy Horder hatches’ and adopt a ‘me first’ and wrongs of Brexit is unlikely to £75 Number 87 Caro & James Simper stance. -

A Pilgrimage to Avebury Stone Circles in Wiltshire

BEST OF BRITAIN A pilgrimage to Avebury stone circles in Wiltshire ere are famous religious pilgrimages, there are also the pilgrimages that one does for oneself. It doesn't have to be on foot or by any particular mode of transport. It is nothing more than the journey of getting to the desired destination, in any way or form. For me, that desired destination was the stone circles of Avebury in Wiltshire, for years I’ve been yearning to sit in stone circles and visit the sacred sites of Europe. So, why visit Avebury, a place that is often sold to us as the poor cousin of the ever-famous Stonehenge? In real - ity, it is not less but much more. Why Avebury? is sacred Neolithic site is the largest set of stone circles out of the thousands in the United Kingdom and in the world. It is older than other sites, although the dating is sketchy. I've heard everything from 2600BC to 4500BC and it’s still up for discussion. Despite being a World Heritage site, Avebury is fully open to the public. Unlike Stonehenge, you can walk in and around the stones. It is accessible by public transport, buses stop in the middle of the village, and the entrance is free. As well as the stone cir - cles, there is also an avenue of stones that take you down to the West Kennet Long Barrow and Silbury Hill. Onsite for a small fee you can visit the museum and manor that are run by the National Trust. -

Concrete Prehistories: the Making of Megalithic Modernism 1901-1939

Concrete Prehistories: The Making of Megalithic Modernism Abstract After water, concrete is the most consumed substance on earth. Every year enough cement is produced to manufacture around six billion cubic metres of concrete1. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern prehistories. We present an archaeology of concrete in the prehistoric landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury, where concrete is a major component of megalithic sites restored between 1901 and 1964. We explore how concreting changed between 1901 and the Second World War, and the implications of this for constructions of prehistory. We discuss the role of concrete in debates surrounding restoration, analyze the semiotics of concrete equivalents for the megaliths, and investigate the significance of concreting to interpretations of prehistoric building. A technology that mixes ancient and modern, concrete helped build the modern archaeological imagination. Concrete is the substance of the modern –”Talking about concrete means talking about modernity” (Forty 2012:14). It is the material most closely associated with the origins and development of modern architecture, but in the modern era, concrete has also been widely deployed in the preservation and display of heritage. In fact its ubiquity means that concrete can justifiably claim to be the single most dominant substance of heritage conservation practice between 1900 and 1945. This paper investigates how concrete has been built into the construction of modern pasts, and in particular, modern prehistories. As the pre-eminent marker of modernity, concrete was used to separate ancient from modern, but efforts to preserve and display prehistoric megaliths saw concrete and megaliths become entangled. -

BA0063 2013-001 Radial Leaded Capacitor Assembly Location Change Notification Jan 13 Final

Syfer Technology Limited Old Stoke Road Arminghall, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 8SQ England Tel: +44 (0)1603 723347 Fax +44 (0)1603 723301 Email: [email protected] Web: www.syfer.com Anglia Sandall Road Wisbech Cambridgeshire PE13 2PS United Kingdom BA0063 February 2013 PCN reference: 2013/01 Subject: Radial Leaded Capacitor Assembly Location Change Dear Customer, Syfer Technology Ltd has been manufacturing radial leaded capacitors at our UK manufacturing facility from the early 1980s. Due to facility space requirements needed to develop and manufacture new products, it has been decided to sub-contract the radial assembly process. Ceramic Chip Capacitor Encapsulation Material Lead to Chip Capacitor Solder Joint Lead Fig. 1. Radial Capacitor Construction Diagram The critical part of the radial component (the ceramic chip capacitor) will still be manufactured, electrically tested and inspected by Syfer. Registered Office: Old Stoke Road Arminghall, Norwich NR14 8SQ England Registered in England: No 2092166 (FA4/971/1) The radial assembly process including soldering leads onto the chip capacitor, encapsulation, print and radial electrical test will be conducted by the sub-contractor. The sub-contractor is certified to ISO9001 and has a proven history of manufacturing and supplying radial leaded capacitors. Syfer has conducted reliability tests on components manufactured by the sub-contractor as part of qualification and ongoing monitoring requirements. The change in location for the radial leaded capacitor assembly does not affect component specifications (including dimensional, performance or reliability) and, as such, there is no change to the Syfer part number. Radial leaded capacitors manufactured by the sub-contractor will gradually be phased into customer supply from March 2013. -

Cuisine and Consumption at the Late Neolithic Site of Durrington Walls

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Feeding Stonehenge: cuisine and consumption at the Late Neolithic site of Durrington Walls Oliver E. Craiga, Lisa-Marie Shillitoa,b, Umberto Albarellac, Sarah Viner-Danielsc, Ben Chanc,d, Ros Cleale, Robert Ixerf, Mandy Jayg, Pete Marshallh., Ellen Simmonsc, Elizabeth Wrightc and Mike Parker Pearsonf aBioArCh, Department of Archaeology, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK. b School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh, UK cDepartment of Archaeology, University of Sheffield, UK d Laboratory for Artefact Studies, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, The Netherlands e Alexander Keiller Museum, Avebury, Wiltshire, UK f Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, UK g Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Department of Human Evolution, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany h English Heritage, 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, UK Introduction Henges are distinctive monuments of the Late Neolithic in Britain, defined as ditched enclosures in which a bank is constructed outside the ditch. The largest is Durrington Walls (Fig 1), a 17ha monument near Stonehenge. Excavations at Durringon Walls from 1966 to 1968 revealed the remains of two timber circles, the Northern and Southern Circles, within the henge enclosure (Wainwright and Longworth, 1971). More recent excavations (2004-2007) have identified a settlement that pre-dates the henge by a few decades and is concurrent with the main construction phase of Stonehenge (Parker Pearson et al., 2007, Parker Pearson, 2007, Thomas, 2007). Middens and pits, with substantial quantities of animal bones, broken Grooved Ware ceramics and other food-related debris, accumulated quickly since the settlement has an estimated start of 2535-2475 cal BC (95% probability) and a use of 0-55 years (95% probability). -

Stonehenge and Avebury WHS Management Plan 2015 Summary

Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Vision The Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site is universally important for its unique and dense concentration of outstanding prehistoric monuments and sites which together form a landscape without parallel. We will work together to care for and safeguard this special area and provide a tranquil, rural and ecologically diverse setting for it and its archaeology. This will allow present and future generations to explore and enjoy the monuments and their landscape setting more fully. We will also ensure that the special qualities of the World Heritage Site are presented, interpreted and enhanced where appropriate, so that visitors, the local community and the whole world can better understand and value the extraordinary achievements © K020791 Historic England © K020791 Historic of the prehistoric people who left us this rich legacy. Avebury Stone Circle We will realise the cultural, scientific and educational potential of the World Heritage Site as well as its social and economic benefits for the community. © N060499 Historic England © N060499 Historic Stonehenge in summer 2 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Management Plan Summary 2015 1 World Heritage Sites © K930754 Historic England © K930754 Historic Arable farming in the WHS below the Ridgeway, Avebury The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site is internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments. Stonehenge is the most architecturally sophisticated prehistoric stone circle in the world, while Avebury is Stonehenge and Avebury were inscribed as a single World Heritage Site in 1986 for their outstanding prehistoric monuments the largest. -

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

WRAP THESIS Shilliam 1986.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/34806 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. FOREIGN INFLUENCES ON AND INNOVATION IN ENGLISH TOMB SCULPTURE IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Nicola Jane Shilliam B.A. (Warwick) Ph.D. dissertation Warwick University History of Art September 1986 SUMMARY This study is an investigation of stylistic and iconographic innovation in English tomb sculpture from the accession of King Henry VIII through the first half of the sixteenth century, a period during which Tudor society and Tudor art were in transition as a result of greater interaction with continental Europe. The form of the tomb was moulded by contemporary cultural, temporal and spiritual innovations, as well as by the force of artistic personalities and the directives of patrons. Conversely, tomb sculpture is an inherently conservative art, and old traditions and practices were resistant to innovation. The early chapters examine different means of change as illustrated by a particular group of tombs. The most direct innovations were introduced by the royal tombs by Pietro Torrigiano in Westminster Abbey. The function of Italian merchants in England as intermediaries between Italian artists and English patrons is considered. Italian artists also introduced terracotta to England. -

4. Vocabulary Cards Rectificado

n. someone who studies the past by recovering and examining remaining material evidence, such archaeologist as graves, buildings, tools, bones and pottery. “ The archaeologist excavated the site.” n. the study of past human life and culture by the recovery and examination of remaining evidence, such archaeology as graves, buildings, bones and pottery. n. someone who lives in a cave. “Prehistoric man found cave dweller shelter in caves. They became cave dwellers.” n. representations of wild, animals, painted on the walls of caves by prehistoric people, using cave painting simple tools such as fingers, twigs and leaves and using colours found in nature such as brown, red, black and green. adj. relating to the period in human culture before the bronze age, characterised by the chalcolithic use of copper and stone. “The bones were dug up at a chalcolithic site. There were bronze tools there, too.” adj. early form of modern human inhabiting Europe in the late paleolithic period (40,000 – 10,000 years cro-magnon ago). Skeletal remains were first found in the Cro- Magnon cave in southern France. “Homo Sapiens is a cro.magnon man.” n. structure usually regarded as a tomb, dolmen consisting of two or more large upright stones set with a space between and capped by a horizontal stone. n. place where archaeologists dig to find evidence of how excavation site humans lived in the past. “The excavation site is full of interesting things we can use to find out about the past.” n. very hard fine- grained quartz that spark when struck. Prehistoric people used flint this to make tools and start fire.