Introduction to Journalism and Mass Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Davis Instruments 2656606 08/01/2014 Cole-Parmer Instrument Company Llc, 625 East Bunker Court, Vernon Hills, Illinois 60061, United States of America

Trade Marks Journal No: 1948 , 18/05/2020 Class 35 DAVIS INSTRUMENTS 2656606 08/01/2014 COLE-PARMER INSTRUMENT COMPANY LLC, 625 EAST BUNKER COURT, VERNON HILLS, ILLINOIS 60061, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Service Providers An Illinois Limited Liability Company Address for service in India/Attorney address: RNA, IP ATTORNEYS 401-402, 4TH FLOOR, SUNCITY SUCCESS TOWER, SEC-65, GOLF COURSE EXTENSION ROAD, GURGAON-122005 NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (HARYANA) Used Since :30/04/2001 DELHI Distribution services, namely, distributing the goods of others in the field of test, measurement, control and calibration equipment and instruments 5101 Trade Marks Journal No: 1948 , 18/05/2020 Class 35 2714032 07/04/2014 RAJUBHAI M. TRIVEDI trading as ;M/S. SAGAR ENTERPRISE 1ST FLOOR, SHOP NO - 1,2,3, NR. SWAGAT HALL, CANAL CHOWKDI, RAVAPAR ROAD, MORBI - 363 641. GUJARAT - INDIA. SERVICE PROVIDER NIL Used Since :29/08/2009 AHMEDABAD SERVICES RELATED TO SHOWROOM AND TRADING OF WALL PAPER, CURTAINS, KOREAN BLINDS, MATTRESSES AND MOSQUITO NETS INCLUDED IN CLASS - 35. 5102 Trade Marks Journal No: 1948 , 18/05/2020 Class 35 2824042 09/10/2014 M K JOKAI AGRI PLANTATIONS PRIVATE LIMITED VRAJ,62/13 PROMOTESH BARUA SARANI (FORMERLY BALLYGUNGE CIRCULAR ROAD),KOLKATA 700019,WEST BENGAL,INDIA SERVICE PROVIDERS AND MERCHANTS A COMPANY REGISTERED IN INDIA. Address for service in India/Agents address: ARJUN T. BHAGAT & CO. 6/B SHAHEEN APARTMENT,132 / 1, MODI STREET, POST BOX NO. 1865, FORT, MUMBAI - 400 001. Proposed to be Used KOLKATA Services relating to export, wholesale & retail of tea, the bringing together for the benefit of others of a variety of such goods as aforementioned thereby enabling customers to conveniently view & purchase those goods in a retail outlet, store; retail services relating to aforementioned goods sold, through web sites or television shopping programmes; presentation of goods on communication media for retail purposes; advertising services included in class 35. -

471-Media Relations.Pdf

9'\ .1 ........- -.! I I I Media Relations I I I I I I I I I I Jnani I ---------------------------------------------------------- I M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation I I I .1 I I Publication Details» I Media Relations I November 2000 I MSSRF/MAlOO/01 Tamil I M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (Project ACCESS) I Funded by Bemard van. Leer Foundation Print A.M.M. Screens I Illustrations Mr. Shyam I Cover design Mr. Jeevamani I I I I M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation 3rd Cross Street Taramani Institutional Area I Taramani" Chennai 600 11:3. I Telephone 91-44-235 ~1229,235 1698 Fax 91-44-235 '1319 I E-mail [email protected] Website htlp://www.rnssrf.org I I I I II dCIIII I I Contents I Why this book? . 1 I Preface . 2 I What is Media? . 3 I Let us understand the media. 11 Why do we need Media? . I 15 Media Strategies . 17 I Our Strategies . 23 I Conclusion . 47 I I I I I ,I I I I I II II I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I Why this book? I Media has become an inalienable part of our lives today. It has become as essential as school, I office, food, clothing and shelter. Among the forces that shape our thoughts and opinions, media plays a key role. Hence NGOs who I are constantly in touch with the general public can neither ignore nor neglect the media. Project ACCESS of M.S. -

Samples of Newspaper Cuttings Regarding ACMEC TRUST's Social

Omsakthi UN PUBLIC SERVICE AWARDS EVIDENCES IN PRINT MEDIA FOR ACMEC TRUST Samples of Newspaper Cuttings (1999 – 2019) Regarding ACMEC TRUST’S Social Welfare Endeavor FIG. – 1A – TAMIL MURASU - Tamil language Newspaper - 7-12-1999 His. Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends Relief materials worth INR.10 Lakhs by train to people affected by flood in Orissa, India. Distribution through 108 volunteers of Adhiparasakthi Worshipping Centres of ACMEC Trust FIG. – 1B. December 9, 1999 –– DINAKARAN – Tamil language Newspaper - His Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends Rs.10 Lakh worth of relief materials sent by Lorry to Cyclone affected Orissa. A team of doctors and 108 volunteers also journey to Orissa to take part in the relief work FIG – 1C. December 12, 1999 –– DINAKARAN - Tamil language Newspaper - His Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends Rs.10 Lakh worth of relief materials sent by Lorry to Cyclone affected Orissa. A team of doctors and 108 volunteers also journey to Orissa to take part in the relief work FIG. – 5B. 9.12.1999 –– MALAI MALAR - His Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends 504 bags of rice, medicines sent to flood affected districts of Trichy &Karur in Tamil Nadu, India. FIG. – 2A. January 28, 2001 –– DHINABOOMI – Tamil Language Newspaper - His Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends Rs.25 Lakh worth of relief materials being sent with volunteers to aid quake-affected Gujarat FIG. – 2B- January 28, 2001 –– DHINABOOMI – Tamil Language Newspaper - His Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends Rs.25 Lakh worth of relief materials being sent with volunteers to aid those affected by earthquake in Gujarat, India FIG. – 2C- January 28, 2001 –– DHINATHANTHI – Tamil Language Newspaper – His Holiness Bangaru Adigalar sends Rs.25 Lakh worth of relief materials being sent with volunteers to aid those affected by earthquake in Gujarat, India. -

To Get the File

Business of Culture in India S. Ananth Research Fellow Krisani Knowledge Resources Hyderabad Project Commissioned by Culture: Industries and Diversity in Asia (CIDASIA) Research Programme Centre for the Study of Culture and Society Bangalore May 2008 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Newspaper Industry in India 3. Filmed Entertainment Market in India 4. Film Distribution – Multiplex Phenomenon 5. Funding the Film Business 6. Overseas Market for Indian Films 7. Home Video Market 8. Television Market in India 9. Cable TV Market in India 10. DTH Market in India 11. IPTV Market in India 12. Radio Market in India 13. Music Market in India 14. Internet Usage in India 15. Gaming Market in India Global Gaming Market 16. Animation Sector in India 17. Amusement Parks in India 18. Retail Market in India 19. Luxury Market in India Luxury Watch Segment in India Luxury Car Segment in India 20. Wedding Market in India 21. Gambling Market in India 22. Advertising Market in India 23. Out of Home Advertising Market in India 24. Art Market in India 25. Sports Market in India Horse Racing In India 26. Entertainment Companies in India 27. Emerging Trends in the Culture Industry 28. Select Bibliography 3 Business of Culture in Contemporary India Introduction This report titled the ‘Business of Culture in India’ attempts to compile statistical information as well as analyse the most important business trends in Culture Industry of contemporary India. The report is meant to provide a snapshot of the major components of the culture industry, the economics of the various components as well as a brief sketch of the regulatory environment in the industry. -

Cabot Sanmar's Fumed Silica Expansion At

1 The Sanmar Group 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. Tel.: + 91 44 2812 8500 Fax.: + 91 44 2811 1902 Sanmar Holdings Ltd Sanmar Consolidations Ltd Chemplast Sanmar Ltd Sanmar Shipping Ltd TCI Sanmar Chemicals S.A.E. Cabot Sanmar Ltd Sanmar Speciality Chemicals Ltd Sanmar Engineering Technologies Ltd - Products Divn. Flowserve Sanmar Ltd BS&B Safety Systems (India) Ltd Xomox Sanmar Ltd Xomox Valves Divn. Pacific Valves Divn. Pentair Sanmar Ltd - Steel Castings Divn. Sanmar Foundries Ltd Matrix Metals LLC 2 In this issue... 4 10 13 The KS Narayanan Oration National Safety Council 2017 recognises Sanmar for 19 safety management 4 Deepak Parekh in conversation with Shekhar practices Gupta The Tenth Annual India Chemplast Sanmar meets Chemical Industry Outlook the Press 20 Conference on Innovation 15 8 Golden Jubilee and Disruption celebrations in the offing; expansion plans unveiled Business Seminar at Cairo by the Embassy of India in Cabot Sanmar’s fumed Egypt silica expansion at Mettur 10 PS Jayaraman a main 25 21 speaker KCP Platinum Jubilee Visit of CII Indian 12 N Sankar recalls Sanmar- Delegation to Cairo KCP family ties Students from Odense, Chemplast organises Denmark in India on a 22 mega medical camps for 14 study tour rural populace Annual Day and Sports Nordic Ambassadors to Chemplast provides Meet at Madhuram India on a week-long financial aid for education 25 Narayanan Centre for 15 tour of Tamil Nadu and 23 and environment upkeep Exceptional Children Puducherry Legends from the South Indian Space Research Donation to Ellen Organisation: Sharma School, 26 Swati Tirunal 16 Pride of Modern India 24 Karapakkam (1813 - 1846) Matrix can be viewed at www.sanmargroup.com Designed and edited by Kalamkriya Limited, 9, Cathedral Road, Chennai 600 086. -

Answered On:19.12.2001 Pm`S Foreign Trips Priya Ranjan Dasmunsi;Uttamrao Deorao Patil

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA EXTERNAL AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:4446 ANSWERED ON:19.12.2001 PM`S FOREIGN TRIPS PRIYA RANJAN DASMUNSI;UTTAMRAO DEORAO PATIL Will the Minister of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) the number of foreign trips our Prime Minister has undertaken since the inception of 13th Lok Sabha till November 15, 2001 including the date and period of stay etc.; (b) the composition of Media contingent-both print and electronic media-including the names of media personnel, electronics media, crew etc. and the names of the newspapers in each trip; (c) whether the media personnel have been looked after at Government cost or they had to pay their telephone and news transmitting charges like Fax, Telex, E-mail or Internet services; and (d) If so, the details thereof Answer THE MINISTER OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (SHRI JASWAT SINGH) (a): The information is placed at Annexure I (b): The information is placed at Annexure II-IX (c & d): The Government does not provide for the boarding and lodging of the media delegation accompanying the Prime Minister on visits abroad. This expenditure, including any on telephone calls and faxes made from respective hotel rooms, are paid for by the media delegates themselves. To facilitate reporting from places visited, the Government arranges a media center with limited communication facilities especially computers with e-mail. Annexure I The Prime Minister had undertaken 8 (eight) trips abroad since the inception of 13th Lok Sabha till November 15, 2001. The details are as under: S.No. Countries Visited Date 1. South Africa November 11-18, 1999 2. -

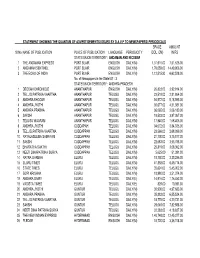

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00 -

Lok Sabha Q No. 2209

STATE WISE PENDENCY SINCE 2015-2016 PENDENCY (Rupees in Cr.) STATE/UT NAME 2015-2016 2016-2017 2017-2018 2018-2019 2019-2020 2020-2021 ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 0.00 0.02 0.01 0.04 0.02 0.02 ANDHRA PRADESH 0.05 0.18 0.18 0.36 0.21 0.35 ARUNACHAL PRADESH 0.01 0.05 0.08 0.07 0.06 0.06 ASSAM 0.04 0.13 0.20 0.33 0.18 0.28 BIHAR 0.12 1.07 1.01 1.21 0.65 0.87 CHANDIGARH 0.07 0.31 0.32 0.39 0.28 0.25 CHHATTISGARH 0.08 0.42 0.28 0.78 0.48 0.55 DADRA AND NAGAR HAVELI 0.01 0.03 0.03 0.07 0.03 0.06 DAMAN AND DIU 0.00 0.03 0.02 0.05 0.03 0.04 DELHI 3.60 9.92 5.31 8.58 6.61 3.77 GOA 0.03 0.07 0.04 0.05 0.05 0.05 GUJARAT 0.27 0.99 0.99 1.20 0.64 0.99 HARYANA 0.08 0.44 0.33 0.30 0.24 0.31 HIMACHAL PRADESH 0.03 0.09 0.06 0.15 0.07 0.09 JAMMU AND KASHMIR 0.09 0.29 0.33 0.69 0.49 0.61 JHARKHAND 0.05 0.34 0.35 0.50 0.33 0.43 KARNATAKA 0.34 0.95 0.61 0.96 0.63 0.69 KERALA 0.07 0.46 0.43 0.56 0.46 0.58 MADHYA PRADESH 0.18 1.27 0.76 1.48 0.90 1.57 MAHARASHTRA 1.04 3.10 2.20 3.72 2.49 2.62 MANIPUR 0.01 0.04 0.04 0.08 0.07 0.10 MEGHALAYA 0.01 0.04 0.04 0.07 0.04 0.06 MIZORAM 0.01 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.05 0.05 NAGALAND 0.01 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.05 0.03 ORISSA 0.12 0.48 0.44 0.99 0.42 0.74 PUDUCHERRY 0.00 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.02 0.02 PUNJAB 0.12 0.45 0.43 0.75 0.39 0.46 RAJASTHAN 0.27 2.25 0.85 1.75 0.93 1.53 SIKKIM 0.02 0.06 0.07 0.06 0.06 0.10 TAMIL NADU 0.20 1.01 0.78 1.11 0.70 0.52 TELANGANA 0.25 0.75 0.72 0.90 0.77 0.70 TRIPURA 0.01 0.06 0.09 0.11 0.09 0.13 UTTAR PRADESH 0.43 2.39 1.52 3.85 1.56 2.40 UTTARAKHAND 0.07 0.31 0.23 0.40 0.26 0.35 WEST BENGAL 0.37 1.69 1.07 1.69 -

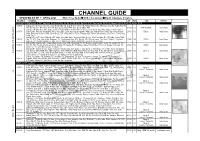

Channel Guide

CHANNEL GUIDE UPDATED AS OF 1ST APRIL 2021 FTA = Free To Air SCR = Scrambled Radio Channels in Italics FREQ/POL CHANNEL SR FEC CAS NOTES INTELSAT-38/AzerSpace2 at 45.1 deg East: Bom Az 238 El 51, Blr Az 250 El 49, Del 232 El 41, Chennai Az 252 El 46, Bhopal Az 238 El 44 Cal Az 248 El 35 11475 V Dialog DTH: Sony Six HD, Discovery World India HD, Star Movies Select HD, Animal Planet HD, AXN East Asia HD, Rugby PassTV S A HD, Star Sports 1 HD, Sony Ten2 HD, Star Sports select HD1, Star Sports Select HD2 32000 2/3 DVB-S2/8PSK India Beam T Dialog DTH: CBeebies Asia, Pogo, Cartoon Network HD+, A Plus Kids TV, Nickelodeon South East Asia, Baby TV Asia, Disney E 11515 V Junior India, National Geographic India, Sony BBC Earth, National Geographic Wild Asia, Animal Planet India, Discovery Channel 23700 5/6 DVB-S India Beam L L India, Discovery Science India, Tech Storm, TLC India, History TV 18, Travelxp HD, Travel Channel Asia, Sony Ten 1, Ten Cricket, I T Sony Ten 2 E Dialog DTH: HGTV Asia, Makeful, SET India, Sony Max India, Star Gold India, Colors, Star Plus India, Zee TV India, Colors Tamil, & 11555 V Sun TV, KTV, Star Vijay India, Kalaignar TV, Zee Cinema Asia, UTV Movies, B4U Movies India, Zee Tamil, Sirippoli, Zing Asia, 27690 3/5 DVB-S India Beam C Supreme TV, DTamil, Fashion TV Asia, Hi TV, NHK World Japan,, WakuWaku Japan South East Asia A Dialog DTH: Channel One, Rupavahini, Channel Eye, ITN, Vasantham TV, TV Derana, Swarnavahini, Sirasa TV, Shakthi TV, TV 1, B 11595 V Hiru TV, TNL TV, Art, Ada Derana 24x7, Siyatha TV, Haritha TV, -

Advisory170910.Pdf

List Of Publishers Who Submitt Their Bills Manually SL.No. NP_CODE NP_NAME PUB_CITY CIRC_ACCEPTED 1 120201 AAJ KA ANAND PUNE 75000 2 127910 AAJ KI REPORT BARABANKI 21077 3 125966 AAKANSHA SAMVAD KANPUR 5300 4 128217 AALLA SANDESH DELHI 41401 5 123559 AAP TAK SAMASTIPUR 55200 6 200238 AAPLA MAHANAGAR MUMBAI 52028 7 210289 AATUR AHMEDABAD 3362 8 121730 ACHARAN SAGAR 27595 9 121952 AFKAR BHOPAL 19500 10 200063 AIKYA SATARA 36691 11 180214 AJ-DI-AWAZ JALANDHAR 75000 12 122494 AJKAL DELHI 6051 13 310624 AJKER FARIAD AGARTALA 43389 14 120281 AKASH MARG DEORIA 31490 15 210027 AKILA RAJKOT 48906 16 160739 AL-YAUM DELHI 44233 17 120052 ALOK REWA 35110 18 160082 AMAL KANPUR 53037 19 123193 AMAR PRAVAKTA BHOPAL 15617 20 320206 AMARI KATHA BHUBANESWAR 9000 21 124727 ANAMIKA SIKAR 6350 22 123416 ANGAD BUNDI 36925 23 124465 APNI RANCHI RANCHI 32145 24 126672 APRANHA TIMES UDAIPUR 27142 25 120065 ARANYACHAL AMBIKAPUR 18203 26 123276 ARTH PARKASH CHANDIGARH 37220 27 580002 AVAKASH PATRIKA JODHPUR 27000 28 120174 AWAZ DHANBAD 32309 29 161274 AWAZ-E-DOST HYDERABAD 12500 30 160411 AZIMABAD MAIL PATNA 46000 31 126957 B.R.TIMES ALLAHABAD 14700 32 125587 BAAT CHAKRA GORAKHPUR 28117 33 127874 BAHUJAN VIKAS DELHI 11950 34 121030 BAL BHARTI DELHI 8667 35 161322 BALRAMPUR EXPRESS LUCKNOW 25500 36 129106 BALRAMPUR TARANG BALRAMPUR 25941 37 120189 BANDEMATARAM DELHI 30807 38 160634 BARQI DUNIA JAMMU 47457 39 300094 BATORI KAKAT GUWAHATI 24515 40 120200 BEROJGAR PATNA 64500 41 120904 BHABHAK AJMER 2700 42 200371 BHAIRAO TIMES RATNAGIRI 25111 43 120194 BHARAT BHAVNA -

UNIT – I– Media Culture and Entertainment– SVCA5201

SCHOOL OF SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF VISUAL COMMUNICATION UNIT – I– Media Culture and Entertainment– SVCA5201 1 UNIT- I 1. Culture: The term “culture‟ refers to the complex collection of knowledge, folklore, language, rules, rituals, habits, lifestyles, attitudes, beliefs and customs that link and give a common identity to a particular group of people at a specific point in time. Ethnic Culture: The term „Ethnic culture‟ refers to the characteristics of a people, sharing a common and distinctive racial, national, religious, linguistic or cultural heritage (For example, the Toda peoples are known as the son of the land in Nilgiris; live in a specific territory, speak their own language and have a social organization distinct from other groups living in that region). Social Culture: All social units develop a culture, even in two- person relationships, a culture is developed, for example in friendship and romantic relationships, the partners develop their own language patterns, rituals, habits and customs that give the relationship a special character, which differentiates it in various ways from other relationships. Group Culture: When a group traditionally meets, whether the meetings begin on time or not, what topics are discussed, how decisions are made and how the group socializes are the elements that define and differentiates group culture. A group that shares a geographic region, a sense of identity and a culture is called a society. Characteristics of Culture: Cultures are complex and complicated „structures‟ that consist of a wide array of characteristics. If other cultures whether of relationships, groups, organizations or societies look different; those differences are often considered to be negative, illogical and sometimes nonsensical.