Making Conformance Work: Constructing Accessibility Standards Compliance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internet Explorer 9 Features

m National Institute of Information Technologies NIIT White Paper On “What is New in Internet Explorer 9” Submitted by: Md. Yusuf Hasan Student ID: S093022200027 Year: 1st Quarter: 2nd Program: M.M.S Date - 08 June 2010 Dhaka - Bangladesh Internet Explorer History Abstract: In the early 90s—the dawn of history as far as the World Wide Web is concerned—relatively few users were communicating across this Internet Explorer 9 (abbreviated as IE9) is the upcoming global network. They used an assortment of shareware and other version of the Internet Explorer web browser from software for Microsoft Windows operating system. In 1995, Microsoft Microsoft. It is currently in development, but developer hosted an Internet Strategy Day and announced its commitment to adding Internet capabilities to all its products. In fulfillment of that previews have been released. announcement, Microsoft Internet Explorer arrived as both a graphical Web browser and the name for a set of technologies. IE9 will have complete or nearly complete support for all 1995: Internet Explorer 1.0: In July 1995, Microsoft released the CSS 3 selectors, border-radius CSS 3 property, faster Windows 95 operating system, which included built-in support for JavaScript and embedded ICC v2 or v4 color profiles dial-up networking and TCP/IP (Transmission Control support via Windows Color System. IE9 will feature Protocol/Internet Protocol), key technologies for connecting to the hardware accelerated graphics rendering using Direct2D, Internet. In response to the growing public interest in the Internet, Microsoft created an add-on to the operating system called Internet hardware accelerated text rendering using Direct Write, Explorer 1.0. -

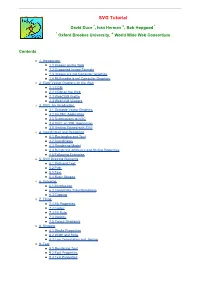

SVG Tutorial

SVG Tutorial David Duce *, Ivan Herman +, Bob Hopgood * * Oxford Brookes University, + World Wide Web Consortium Contents ¡ 1. Introduction n 1.1 Images on the Web n 1.2 Supported Image Formats n 1.3 Images are not Computer Graphics n 1.4 Multimedia is not Computer Graphics ¡ 2. Early Vector Graphics on the Web n 2.1 CGM n 2.2 CGM on the Web n 2.3 WebCGM Profile n 2.4 WebCGM Viewers ¡ 3. SVG: An Introduction n 3.1 Scalable Vector Graphics n 3.2 An XML Application n 3.3 Submissions to W3C n 3.4 SVG: an XML Application n 3.5 Getting Started with SVG ¡ 4. Coordinates and Rendering n 4.1 Rectangles and Text n 4.2 Coordinates n 4.3 Rendering Model n 4.4 Rendering Attributes and Styling Properties n 4.5 Following Examples ¡ 5. SVG Drawing Elements n 5.1 Path and Text n 5.2 Path n 5.3 Text n 5.4 Basic Shapes ¡ 6. Grouping n 6.1 Introduction n 6.2 Coordinate Transformations n 6.3 Clipping ¡ 7. Filling n 7.1 Fill Properties n 7.2 Colour n 7.3 Fill Rule n 7.4 Opacity n 7.5 Colour Gradients ¡ 8. Stroking n 8.1 Stroke Properties n 8.2 Width and Style n 8.3 Line Termination and Joining ¡ 9. Text n 9.1 Rendering Text n 9.2 Font Properties n 9.3 Text Properties -- ii -- ¡ 10. Animation n 10.1 Simple Animation n 10.2 How the Animation takes Place n 10.3 Animation along a Path n 10.4 When the Animation takes Place ¡ 11. -

SVG Programming: the Graphical Web

SVG Programming: The Graphical Web KURT CAGLE APress Media, LLC SVG Programming: The Graphical Web Copyright © 2002 by Kurt Cagle Originally published by Apress in 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copy right owner and the publisher. ISBN 978-1-59059-019-5 ISBN 978-1-4302-0840-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4302-0840-2 Trademarked names may appear in this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Technical Reviewer: Don Demcsak Editorial Directors: Dan Appleman, Peter Blackburn, Gary Cornell, Jason Gilmore, Karen Watterson, John Zukowski Project Manager: Tracy Brown Collins Copy Editor: Kim Wirnpsett Production Editor: Grace Wong Compositor: Impressions Book and Journal Services, Inc. Indexer: Ron Strauss Cover Designer: Kurt Krames Manufacturing Manager: Tom Debolski Marketing Manager: Stephanie Rodriguez In the United States, phone 1-800-SPRINGER, email orders@springer-ny. com, or visit http:llwww.springer-ny.com. Outside the United States, fax +49 6221 345229, email orders@springer. de, or visit http:llwww.springer.de. For information on translations, please contact Apress directly at 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 219, Berkeley, CA94710. Phone 510-549-5930, fax: 510-549-5939, email [email protected], or visit http: I lwww. -

Web 2D Graphics: State-Of-The-Art

Web 2D Graphics: State-of-the-Art © David Duce, Ivan Herman, Bob Hopgood 2001 Contents l 1. Introduction ¡ 1.1 Images on the Web ¡ 1.2 Supported Image Formats ¡ 1.3 Images are not Computer Graphics l 2. Early Vector Graphics on the Web ¡ 2.1 CGM ¡ 2.2 CGM on the Web ¡ 2.3 WebCGM Profile ¡ 2.4 WebCGM Viewers l 3. SVG: an Introduction ¡ 3.1 Arrival of XML ¡ 3.2 Submissions to W3C ¡ 3.3 SVG: an XML Application ¡ 3.4 An introduction to SVG ¡ 3.5 Coordinate Systems ¡ 3.6 Path Expressions ¡ 3.7 Other Drawing Elements l 4. Rendering the SVG Drawing ¡ 4.1 Visual Aspects ¡ 4.2 Text ¡ 4.3 Styling l 5. Filter Effects l 6. Animation ¡ 6.1 Introduction ¡ 6.2 What is Animated ¡ 6.3 How the Animation Takes Place ¡ 6.4 When the Animation Take Place l 7. Scripting and the DOM l 8. Current State and the Future ¡ 8.1 Implementations ¡ 8.2 Metadata ¡ 8.3 Extensions to SVG l A. Filter Primitives in SVG l References -- 1 -- © David Duce, Ivan Herman, Bob Hopgood 2001 1. Introduction l 1.1 Images on the Web l 1.2 Supported Image Formats l 1.3 Images are not Computer Graphics 1.1 Images on the Web The early browsers for the Web were predominantly aimed at retrieval of textual information. Tim Berners-Lee's original browser for the NeXT computer did allow images to be viewed but they popped up in a separate window and were not an integral part of the Web page. -

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.2

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.2 Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.2 W3C Working Draft 27 October 2004 This version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-SVG12-20041027/ Previous version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/WD-SVG12-20040510/ Latest version of SVG 1.2: http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG12/ Latest SVG Recommendation: http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG/ Editor: Dean Jackson, W3C, <[email protected]> Authors: See Author List Copyright ©2004 W3C® (MIT, ERCIM, Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark and document use rules apply. Abstract SVG is a modularized XML language for describing two-dimensional graphics with animation and interactivity, and a set of APIs upon which to build graphics- based applications. This document specifies version 1.2 of Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG). Status of this Document http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG12/ (1 of 10)30-Oct-2004 04:30:53 Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.2 This section describes the status of this document at the time of its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. A list of current W3C publications and the latest revision of this technical report can be found in the W3C technical reports index at http://www.w3.org/TR/. This is a W3C Last Call Working Draft of the Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.2 specification. The SVG Working Group plans to submit this specification for consideration as a W3C Candidate Recommendation after examining feedback to this draft. Comments for this specification should have a subject starting with the prefix 'SVG 1.2 Comment:'. Please send them to [email protected], the public email list for issues related to vector graphics on the Web. -

SVG for Graphics and Structure

Using SVG as the Rendering Model for Structured and Graphically Complex Web Material Julius C. Mong and David F. Brailsford Electronic Publishing Research Group School of Computer Science & IT University of Nottingham Nottingham NG8 1BB, UK {jxm,dfb}@cs.nott.ac.uk ABSTRACT resulting bitmap graphics are resolution-dependent. The World This paper reports some experiments in using SVG (Scalable Wide Web Consortium (W3C), aware of the need for a flexible Vector Graphics), rather than the browser default of vector graphics format for the Web, set up a working group in (X)HTML/CSS, as a potential Web-based rendering technology, 1998, charged with drawing up draft proposals for Scalable in an attempt to create an approach that integrates the structural Vector Graphics (SVG) to be expressed in XML-compliant and display aspects of a Web document in a single XML- syntax. The advantages of vector graphics in terms of graphical compliant envelope. precision and scalability become very apparent in material such as maps, line-diagrams and block schematics. The involvement of Although the syntax of SVG is XML based, the semantics of the Adobe Systems Inc on the SVG working group did much to primitive graphic operations more closely resemble those of page ensure that although SVG was syntactically XML-compliant the description languages such as PostScript or PDF. The principal actual graphical semantics of its behaviour resembled, fairly usage of SVG, so far, is for inserting complex graphic material closely, those of its PostScript and PDF page description into Web pages that are predominantly controlled via (X)HTML languages. -

Ethical Web Development

COMP-496: Ethical Web Development Cybersecurity & Networking Seminar It is difficult ot get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it. —Upton Sinclair, Oakland Tribune, December 11, 1934 The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them. —Ida B. Wells Institution Olivet Nazarene University School Martin D. Walker School of Engineering and Technology Department Computer Science and Emerging Technologies Term Spring 2020 Meeting Location Reed Hall of Science 212 Meeting Time Tuesdays 5:30 p.m.–8:00 p.m. Credit Hours 2 Instructor Rev. Reuben L. Lillie, MM, MDiv Office Reed Hall of Science 324A Office Hours Tuesdays 10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m. or by appointment 1 Lillie 2 1. Course Description This course introduces modern best practices for developing a more humane web. Students will explore the ethical ramifications behind ariousv software decisions, including web performance, security, and user/developer experience. The course simulates a team-based working environment in which students will build individual portfolios exhibiting job-ready, front-end skills. In the process, students will learn to leverage modern JavaScript, CSS, Markdown, Git, intrinsic design principles, and static site generation. No prior coding experience necessary. 2. Course Rationale In keeping with Olivet’s mission, this course provides a vital space for the University to explore “web development with a Christian purpose” together. Other courses in the curriculum are designed specifically for advanced computer science students who have met several prerequisites. By lowering the barrier to entry, however, this course invites students from a variety of fields to learn with and from one another. -

Web Standards.Pdf

BOOKS FOR PROFESSIONALS BY PROFESSIONALS® Sikos, Ph.D. RELATED Web Standards Web Standards: Mastering HTML5, CSS3, and XML gives you a deep understand- ing of how web standards can be applied to improve your website. You will also find solutions to some of the most common website problems. You will learn how to create fully standards-compliant websites and provide search engine-optimized Web documents with faster download times, accurate rendering, lower development costs, and easy maintenance. Web Standards: Mastering HTML5, CSS3, and XML describes how you can make the most of web standards, through technology discussions as well as practical sam- ple code. As a web developer, you’ll have seen problems with inconsistent appearance and behavior of the same site in different browsers. Web standards can and should be used to completely eliminate these problems. With Web Standards, you’ll learn how to: • Hand code valid markup, styles, and news feeds • Provide meaningful semantics and machine-readable metadata • Restrict markup to semantics and provide reliable layout • Achieve full standards compliance Web standardization is not a sacrifice! By using this book, we can create and maintain a better, well-formed Web for everyone. CSS3, and XML CSS3, Mastering HTML5, US $49.99 Shelve in Web Development/General User level: Intermediate–Advanced SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com www.it-ebooks.info For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. Please use the Bookmarks and Contents at a Glance links to access them. www.it-ebooks.info Contents at a Glance About the Author................................................................................................ -

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.1 Specification

Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) 1.1 Specification W3C Recommendation 14 January 2003 This version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-SVG11-20030114/ Latest version: http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG11/ Previous version: http://www.w3.org/TR/2002/PR-SVG11-20021115/ Editors: Jon Ferraiolo, Adobe Systems <[email protected]> (version 1.0) •• • (FUJISAWA Jun), Canon <[email protected]> (modularization and DTD) Dean Jackson, W3C/CSIRO <[email protected]> (version 1.1) Authors: See author list Please refer to the errata for this document, which may include some normative corrections. This document is also available in these non-normative packages: zip archive of HTML (without external dependencies) and PDF. See also the translations of this document. Copyright © 2003 W3C® (MIT, ERCIM, Keio), All Rights Reserved. W3C liability, trademark, document use and software licensing rules apply. Abstract This specification defines the features and syntax for Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) Version 1.1, a modularized language for describing two-dimensional vector and mixed vector/raster graphics in XML. Status of this document This section describes the status of this document at the time of its publication. Other documents may supersede this document. The latest status of this document series is maintained at the W3C. This document is the 14 January 2003 Recommendation of the SVG 1.1 specification. SVG 1.1 serves two purposes: to provide a modularization of SVG based on SVG 1.0 and to include the errata found so far in SVG 1.0. The SVG Working Group believes SVG 1.1 has been widely reviewed by the community, developers and other W3C groups. -

Using Inkscape and Scribus to Increase Business Productivity

MultiSpectra Consultants White Paper Using Inkscape and Scribus to Increase Business Productivity Dr. Amartya Kumar Bhattacharya BCE (Hons.) ( Jadavpur ), MTech ( Civil ) ( IIT Kharagpur ), PhD ( Civil ) ( IIT Kharagpur ), Cert.MTERM ( AIT Bangkok ), CEng(I), FIE, FACCE(I), FISH, FIWRS, FIPHE, FIAH, FAE, MIGS, MIGS – Kolkata Chapter, MIGS – Chennai Chapter, MISTE, MAHI, MISCA, MIAHS, MISTAM, MNSFMFP, MIIBE, MICI, MIEES, MCITP, MISRS, MISRMTT, MAGGS, MCSI, MIAENG, MMBSI, MBMSM Chairman and Managing Director, MultiSpectra Consultants, 23, Biplabi Ambika Chakraborty Sarani, Kolkata – 700029, West Bengal, INDIA. E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://multispectraconsultants.com Businesses are under continuous pressure to cut costs and increase productivity. In modern businesses, computer hardware and software and ancillaries are a major cost factor. It is worthwhile for every business to investigate how best it can leverage the power of open source software to reduce expenses and increase revenues. Businesses that restrict themselves to proprietary software like Microsoft Office get a raw deal. Not only do they have to pay for the software but they have to factor-in the cost incurred in every instance the software becomes corrupt. This includes the fee required to be paid to the computer technician to re-install the software. All this creates a vicious environment where cost and delays keep mounting. It should be a primary aim of every business to develop a system where maintenance becomes automated to the maximum possible extent. This is where open source software like LibreOffice, Apache OpenOffice, Scribus, GIMP, Inkscape, Firefox, Thunderbird, WordPress, VLC media player, etc. come in. My company, MultiSpectra Consultants, uses open source software to the maximum possible extent thereby streamlining business processes. -

Workshop HTML5 & SVG in Cartography

Workshop HTML5 & SVG in Cartography Version 2 Table of Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................................1 Instructions...............................................................................................................................................1 Files..........................................................................................................................................................2 Step-by-step Tutorial................................................................................................................................2 Basic HTML document and its structure.............................................................................................2 SVG Basics – First Map Symbols.......................................................................................................3 Interactivity & Gradients.....................................................................................................................4 SVG Advanced....................................................................................................................................7 Back to HTML (Styles, Multimedia).................................................................................................12 Local Storage.....................................................................................................................................16 Navigation.........................................................................................................................................19 -

Making Conformance Work: Constructing Accessibility Standards Compliance

Making Conformance Work: Constructing Accessibility Standards Compliance by Alison Benjamin A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Information Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Alison Benjamin Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-72518-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-72518-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. without the author’s permission.