Part One an Overview of China Chapter 1 the Land and the People 地理条件与人文概况

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

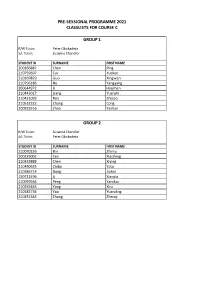

Classlists for C by Group

PRE-SESSIONAL PROGRAMME 2021 CLASSLISTS FOR COURSE C GROUP 1 R/W Tutor: Peter Obukadeta S/L Tutor: Suzanne Chandler STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200166887 Chen Ping 210759697 Cui Yuekun 210169829 Guo Xingwen 210796186 Hu Yangyang 200644972 Li Haozhan 210443017 Liang Yuanzhi 210421093 Ren Zhijiao 210532322 Zhang Cong 200925516 Zhao Yashan GROUP 2 R/W Tutor: Suzanne Chandler S/L Tutor: Peter Obukadeta STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210070226 Bin Zhimu 200329002 Cen Xiaofeng 210333888 Chen Xiying 210450635 Chiba Yota 210386714 Dong Jiahui 190711496 Li Xiaoxia 210059564 Peng Yanduo 210255465 Yang Xiru 210182736 Yao Yuanding 210252383 Zhang Zhenqi GROUP 3 R/W Tutor: Mark Heffernan S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210154386 Cai Zhenping 210462580 Ge Xiaodan 210648276 Hirunkhajonrote Kullanut 210182714 Huang Siwei 200141563 Kung Tzu-Ning 200305176 Punsri Punnatorn 200664774 Sayin Humeyra 210186446 Shehata Omar 171003323 Tutberidze Tea 200134624 Wang Shuo 200136019 Xu Ming 200278696 Yan Jiaxin 210357851 Yuan Lai 210029165 Zhang Anru 210219777 Zhang Jiasheng GROUP 4 R/W Tutor: Sherin White S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200247588 Chen Chong 200349343 Li Cheng 210622933 Liang Wenxuan 210219618 Liu Huiyuan 210376298 Liu Zeyu 210237531 Mei Lyuke 200132620 Qi Shuyu 210681907 Wang Handuo 200015356 Wu Zhuoyue 200071994 Xie Kaijun GROUP 5 R/W Tutor: Chukwudi Dozie S/L Tutor: Nora Mikso STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210563304 Almalek Ahmed 210186309 Altamimi Saud 210251102 Cheng Han-Yu 210349823 Guo Wenyuan 210239409 -

French Names Noeline Bridge

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 13:00 Page 8 The hundred surnames Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Zang Tsang Zang Lin Zhu Chu Gee Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhu Xi Zeng Tseng Tsang, Zeng Cai, Zeng Gong Zhu Chu Zhu Danian Dong, Zhu Chu Zhu Zhishan, Zhu Weihao Jeng Zhu Chu Zhu jin, Zhu Sheng Zha Cha Zha Yihuang, Zhuang Chuang Zhuang Zhou, Zhuang Zi Zha Shenxing Zhuansun Chuansun Zhuansun Shi Zhai Chai Zhai Jin, Zhai Shan Zhuge Chuko Zhuge Liang, Zhan Chan Zhan Ruoshui Zhuge Kongming Zhan Chan Chaim Zhan Xiyuan Zhuo Cho Zhuo Mao Zhang Chang Zhang Yuxi Zi Tzu Zi Rudao Zhang Chang Cheung, Zhang Heng, Ziche Tzuch’e Ziche Zhongxing Chiang Zhang Chunqiao Zong Tsung Tsung, Zong Xihua, Zhang Chang Zhang Shengyi, Dung Zong Yuanding Zhang Xuecheng Zongzheng Tsungcheng Zongzheng Zhensun Zhangsun Changsun Zhangsun Wuji Zou Tsou Zou Yang, Zou Liang, Zhao Chao Chew, Zhao Kuangyin, Zou Yan Chieu, Zhao Mingcheng Zu Tsu Zu Chongzhi Chiu Zuo Tso Zuo Si Zhen Chen Zhen Hui, Zhen Yong Zuoqiu Tsoch’iu Zuoqiu Ming Zheng Cheng Cheng, Zheng Qiao, Zheng He, Chung Zheng Banqiao The hundred surnames is one of the most popular reference Zhi Chih Zhi Dake, Zhi Shucai sources for the Han surnames. It was originally compiled by an Zhong Chung Zhong Heqing unknown author in the 10th century and later recompiled many Zhong Chung Zhong Shensi times. The current widely used version includes 503 surnames. Zhong Chung Zhong Sicheng, Zhong Xing The Pinyin index of the 503 Chinese surnames provides an access Zhongli Chungli Zhongli Zi to this great work for Western people. -

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

Cha Zhang, Chang−Shui Zhang, Chengcui Zhang, Dengsheng Zhang, Dong Zhang, Dongming Zhang, Hong−Jiang Zhang, Jiang Zhang, Jianning Zhang, Keqi Zhang, Lei Zhang, Li

Z Zeng, Wenjun Zeng, Zhihong Zhai, Yun Zhang, Benyu Zhang, Cha Zhang, Chang−Shui Zhang, Chengcui Zhang, Dengsheng Zhang, Dong Zhang, Dongming Zhang, Hong−Jiang Zhang, Jiang Zhang, Jianning Zhang, Keqi Zhang, Lei Zhang, Li Menu Next Z Zhang, Like Zhang, Meng Zhang, Mingju Zhang, Rong Zhang, Ruofei Zhang, Weigang Zhang, Yongdong Zhang, Yun−Gang Zhang, Zhengyou Zhang, Zhenping Zhang, Zhenqiu Zhang, Zhishou Zhang, Zhongfei (Mark) Zhao, Frank Zhao, Li Zhao, Na Prev Menu Next Z Zheng, Changxi Zheng, Yizhan Zhi, Yang Zhong, Yuzhuo Zhou, Jin Zhu, Jiajun Zhu, Xiaoqing Zhu, Yongwei Zhuang, Yueting Zimmerman, John Zoric, Goranka Zou, Dekun Prev Menu Wenjun Zeng Organization : University of Missouri−Columbia, United States of America Paper(s) : ON THE RATE−DISTORTION PERFORMANCE OF DYNAMIC BITSTREAM SWITCHING MECHANISMS (Abstract) Letter−Z Menu Zhihong Zeng Organization : University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign, United States of America Paper(s) : AUDIO−VISUAL AFFECT RECOGNITION IN ACTIVATION−EVALUATION SPACE (Abstract) Letter−Z Menu Yun Zhai Organization : University of Central Florida, United States of America Paper(s) : AUTOMATIC SEGMENTATION OF HOME VIDEOS (Abstract) Letter−Z Menu Benyu Zhang Organization : Microsoft Research Asia, China Paper(s) : SUPERVISED SEMI−DEFINITE EMBEDING FOR IMAGE MANIFOLDS (Abstract) Letter−Z Menu Cha Zhang Organization : Microsoft Research, United States of America Paper(s) : HYBRID SPEAKER TRACKING IN AN AUTOMATED LECTURE ROOM (Abstract) Letter−Z Menu Chang−Shui Zhang Organization : Tsinghua University, China -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: a Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: A Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012 The dragon begets dragon, the phoenix begets phoenix, and the son of the rat digs holes in the ground (traditional saying). This paper estimates the rate of intergenerational social mobility in Late Imperial, Republican and Communist China by examining the changing social status of originally elite surnames over time. It finds much lower rates of mobility in all eras than previous studies have suggested, though there is some increase in mobility in the Republican and Communist eras. But even in the Communist era social mobility rates are much lower than are conventionally estimated for China, Scandinavia, the UK or USA. These findings are consistent with the hypotheses of Campbell and Lee (2011) of the importance of kin networks in the intergenerational transmission of status. But we argue more likely it reflects mainly a systematic tendency of standard mobility studies to overestimate rates of social mobility. This paper estimates intergenerational social mobility rates in China across three eras: the Late Imperial Era, 1644-1911, the Republican Era, 1912-49 and the Communist Era, 1949-2012. Was the economic stagnation of the late Qing era associated with low intergenerational mobility rates? Did the short lived Republic achieve greater social mobility after the demise of the centuries long Imperial exam system, and the creation of modern Westernized education? The exam system was abolished in 1905, just before the advent of the Republic. Exam titles brought high status, but taking the traditional exams required huge investment in a form of “human capital” that was unsuitable to modern growth (Yuchtman 2010). -

Self-Study Syllabus on Chinese Foreign Policy

Self-Study Syllabus on Chinese Foreign Policy www.mandarinsociety.org PrefaceAbout this syllabus with China’s rapid economic policymakers in Washington, Tokyo, Canberra as the scale and scope of China’s current growth, increasing military and other capitals think about responding to involvement in Africa, China’s first overseas power,Along and expanding influence, Chinese the challenge of China’s rising power. military facility in Djibouti, or Beijing’s foreign policy is becoming a more salient establishment of the Asian Infrastructure concern for the United States, its allies This syllabus is organized to build Investment Bank (AIIB). One of the challenges and partners, and other countries in Asia understanding of Chinese foreign policy in that this has created for observers of China’s and around the world. As China’s interests a step-by-step fashion based on one hour foreign policy is that so much is going on become increasingly global, China is of reading five nights a week for four weeks. every day it is no longer possible to find transitioning from a foreign policy that was In total, the key readings add up to roughly one book on Chinese foreign policy that once concerned principally with dealing 800 pages, rarely more than 40–50 pages will provide a clear-eyed assessment of with the superpowers, protecting China’s for a night. We assume no prior knowledge everything that a China analyst should know. regional interests, and positioning China of Chinese foreign policy, only an interest in as a champion of developing countries, to developing a clearer sense of how China is To understanding China’s diplomatic history one with a more varied and global agenda. -

The Outlaws of the Marsh

The Outlaws of the Marsh Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong The Outlaws of the Marsh Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong • Chapter 1 Zhang the Divine Teacher Prays to Dispel a Plague Marshal Hong Releases Demons by Mistake • Chapter 2 Arms Instructor Wang Goes Secretly to Yanan Prefecture Nine Dragons Shi Jin Wreaks Havoc in Shi Family Village • Chapter 3 Master Shi Leaves Huayin County at Night Major Lu Pummels the Lord of the West • Chapter 4 Sagacious Lu Puts Mount Wutai in an Uproar Squire Zhao Repairs Wenshu Monastery • Chapter 5 Drunk, the Little King Raises the Gold−Spangled Bed Curtains Lu the Tattooed Monk Throws Peach Blossom Village into Confusion • Chapter 6 Nine Dragons Shi Jin Robs in Red Pine Forest Sagacious Lu Burns Down Waguan Monastery • Chapter 7 The Tattooed Monk Uproots a Willow Tree Lin Chong Enters White Tiger Inner Sanctum by Mistake • Chapter 8 Arms Instructor Lin Is Tattooed and Exiled to Cangzhou Sagacious Lu Makes a Shambles of Wild Boar Forest • Chapter 9 Chai Jin Keeps Open House for All Bold Men Lin Chong Defeats Instructor Hong in a Bout with Staves • Chapter 10 Lin Chong Shelters from the Snowstorm in the Mountain Spirit Temple Captain Lu Qian Sets Fire to the Fodder Depot • Chapter 11 Zhu Gui Shoots a Signal Arrow from the Lakeside Pavilion Lin Chong Climbs Mount Liangshan in the Snowy Night • Chapter 12 Lin Chong Joins the Bandits in Liangshan Marsh Yang Zhi Sells His Sword in the Eastern Capital • Chapter 13 The Blue−Faced Beast Battles in the Northern Capital Urgent Vanguard Vies for Honors on the Training Field -

Professional Identity, Learning Experience and Teaching Culture Zhang, Chun

Aalborg Universitet Becoming a 'good' Chinese language teacher Professional identity, learning experience and teaching culture Zhang, Chun DOI (link to publication from Publisher): 10.5278/vbn.phd.hum.00040 Publication date: 2016 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Zhang, C. (2016). Becoming a 'good' Chinese language teacher: Professional identity, learning experience and teaching culture. Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Ph.d.-serien for Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Aalborg Universitet https://doi.org/10.5278/vbn.phd.hum.00040 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 26, 2021 BECOMING A ‘GOOD’ CHINESE LANGUAGE TEACHER ‘GOOD’ A BECOMING BECOMING A ‘GOOD’ CHINESE LANGUAGE TEACHER PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY, LEARNING EXPERIENCE AND TEACHING CULTURE BY CHÚN ZHĀNG DISSERTATION SUBMITTED 2016 CHÚN ZHĀNG BECOMING A ‘GOOD’ CHINESE LANGUAGE TEACHER: PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY, LEARNING EXPERIENCE AND TEACHING CULTURE by Chún Zhāng Dissertation submitted . -

Persistent Misconceptions About Chinese “Legalism” Paul R

Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese “Legalism” Paul R. Goldin The reasons for avoiding the term “legalism” in the study of classical Chinese philosophy were summarized years ago by Herrlee G. Creel, 1 and most scholars would probably agree, if pressed, that the term is flawed, and yet one continues to find it deployed in published books and articles—almost as though no one is prepared to admit that it has to be abandoned. 2 I believe that “legalism” is virtually useless as a hermeneutic lens; indeed, in many contexts it obscures more than it clarifies. Even as a bibliographical category, as it was frequently used in imperial times, its value is questionable. In the following pages, I shall first review the weaknesses of the term “legalism,” then ask why scholars persist in adopting it even though they can hardly be unaware of its defects, and finally suggest a better approach to the material that is conventionally categorized as “legalist.” * * * “Legalism” is an imprecise Sinological translation of the Chinese term fajia 法家 . 1 “The fa-chia : ‘Legalists’ or ‘Administrators’?” (1961), reprinted in Creel’s What Is Taoism? and Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 92-120. It should be noted that in his earlier publications, such as Chinese Thought from Confucius to Mao Tse-tung (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), Creel seemed comfortable with the term. 2 Lest readers suppose that I am arguing against a straw man, consider the following titles, published just since 2000, using the term “Legalism” (or some cognate): Roger Boesche, “Han Feizi’s Legalism versus Kautilya’s Arthashastra ,” Asian Philosophy 15.2 (2005), 157-72; idem , “Kautilya’s Arthashastra and the Legalism of Lord Shang,” Journal of Asian History 42.1 (2008), 64-90; Hans van Ess, “Éducation classique, éducation légiste sous les Han,” in Education et instruction en Chine , ed. -

An Introduction to Hanfei's Political Philosophy

An Introduction to Hanfei’s Political Philosophy An Introduction to Hanfei’s Political Philosophy: The Way of the Ruler By Henrique Schneider An Introduction to Hanfei’s Political Philosophy: The Way of the Ruler By Henrique Schneider This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Henrique Schneider All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0812-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0812-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction – Hanfei, Legalism, Chinese Philosophy Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 27 Methodology – Reading Hanfei as a “Social Scientist”? Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 43 History – If Unimportant, Why Look at the Past? Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 65