Color Bind Jacob N. Shapiro and Dara Kay Cohen Lessons from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

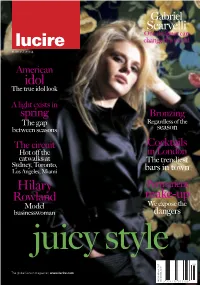

Lucire August 2004

Gabriel Scarvelli One designer can change the world august 2004 American idol The true idol look A light exists in spring Bronzing The gap Regardless of the between seasons season The circuit Cocktails Hot o\ the in London catwalks at The trendiest Sydney, Toronto, Los Angeles, Miami bars in town Hilary Permanent Rowland make-up Model We expose the businesswoman dangers juicy style 0 8 GST The global fashion magazine | www.lucire.com incl. http://lucire.com 1175-7515 1 $9·45 NZ ISSN 9 7 7 1 1 7 5 5 7 5 1 0 0 THIS MONTH THIS Volante travel now | feature Sail of the century You had the spring to spend time with the family. Now it’s the northern summer, the cruise lines are banking on self-indulgence being the order of the day compiled by Jack Yan far left: Fine dining aboard the Holland American Line. above left and above: Sophia Loren, godmother to the MSC Opera, accompanied by Capts Giuseppe Cocurullo and Gianluigi Aponte. left: The new KarView monitor. hold as many as 1,756 guests. The two pools, two hydro-massages and internet café are worthy of mention. Meanwhile, Crystal Cruises is announc- ing theme cruises for those who wish to ast month, it was about families. This ready amazing menu offering. Other signature indulge their passion while getting away. The month, it’s about luxurious self-indulgence entrées include chicken marsala with Wash- company highlights: ‘Garden Design sailings as the summer sailing season begins. As ington cherries and cedar planked halibut with through the British Isles; a Fashion & Style Cunard’s Queen Mary 2 sailed in to New Alaskan king crab. -

Loreto-Chronicle-June-2013

Print Post Approved No. PP 451 207/00 220 ChronicleLoreto Volume 26 No.1 June 2013 From the Principal n this our 85th Anniversary IYear, it gives me great pleasure as a past pupil, a past The Year staff member and now as the Principal of this fine school to “unveil” the much anticipated This is an edited extract from the College Master Plan. ofaddress Justice by College Captains, Laura Sclavos and Emmeline-Kate Ball, at This is a pivotal time in our the Opening Assembly. (L-R) Laura Sclavos & Emmeline-Kate Ball history as we look to further develop the school in exciting ways to cater new year – an entire year’s worth true, Justice is more than that. It is about not only for our increase in enrolment when Aof wonderful opportunities! Many of choosing to do what is right, even when it is we introduce Year 7’s in 2015, but to seize the the moments in the year ahead will be the most difficult option. It is about being able opportunity, as the custodians of Loreto’s future, disguised as ordinary days, but each one to recognise the prejudice that is in our world to do this in a way that maximises the great of us has the chance to make something and respond with compassion to make a potential of this beautiful campus. extraordinary out of them. The year difference. To be Just is to have courage and Vitally important elements of the Master Planning ahead will no doubt be overwhelming wisdom to give a voice to the voiceless and process, which has been conducted for the and challenging at times. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

An early photo of the Gippsland Standard production room. The newspaper—initially called the Gippsland Standard and Alberton, Foster, Port Albert, Tarraville, Woodside, Woranga and Yarram Representative— began at Port Albert, Victoria, on 5 March 1875. It later moved to Yarram and continued publication until 29 September 1971. It amalgamated with the Yarram News and became the Yarram Standard News. In 2009, it became the Yarram Standard. It ceased publication, during COVID-19, in March 2020. The photo shows John Rossiter (white beard), and a son, Augustus John (centre), with two employees. Some of the old type cases, make-up benches and machinery remained in the office in 1975. This image was featured in publicity material at the centenary celebration of the Victorian Country Press Association in 2010. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 112 May 2021 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, F. R. Hist. S. Q., of U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected]/ Published in memory of Victor Mark Isaacs (1949-2019), founding editor. Back copies of the Newsletter and copies of some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 15 July 2021. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000; the Newsletter has appeared five times a year since 2001. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 112.1.1 Shift in Fairfax emphasis on Nine board, and new CEO Board: Fairfax Media’s influence in the Nine Entertainment Co boardroom is close to ending with the resignation of a key director and uncertainty over the future of two other directors with ties to the historic publisher (Sydney Morning Herald, 1 March 2021). -

Issue No. 860 | March 2021

________________________________________________________________________________________________________ - THE RHSQ Bulletin 78 years of continuous publication MARCH 2021 No. 860 The newsletter of The Royal Historical Society of Queensland Patron: His Excellency the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Governor of Queensland President: Dr Denver Beanland AM Website: www.queenslandhistory.org ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ MARCH 31, 2021: 100 YEARS OF SERVICE BY THE ROYAL AUSTRALIAN AIR FORCE RAAF Museum Photo An Avro 504 trainer On 31 March 1921 the RAAF became a separate service. Aircraft flown at that time mainly con- sisted of aircraft received as part of the Imperial Gift. The Avro 504K, 20 of which were ordered in 1918 and another 35 received as part of the Imperial Gift, became an important part of the newly-formed RAAF's operational capability throughout the 1920s. The Imperial Gift was Britain's donation of aero- planes and equipment to the Dominions in 1919 to establish air forces. The only original surviving Impe- rial Gift aircraft in Australia are Avro 504K A3-4/H2174, stored at the Treloar Technology Centre (Can- berra) and S.E.5a A2-4/C1916, exhibited in the ANZAC Hall of the main Australian War Memorial dis- plays in the Australian War Memorial. PER ARDUA AD ASTRA ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The RHSQ Bulletin, March 2021 – Page 2 President’s Report Your Society held its first function of the year on Friday 12 February with the successful launch of the Dig Tree Blazes Exhibition by the Assistant Minister to the Attorney-General Senator the Honourable Amanda Stoker. The social occasion took the form of a wine and cheese with orange juice for those that prefer something lighter. -

8695.5 Tables

Saturday, March 17, 2007 Volume 50, Number 9 Daily Bulletin 50th Spring North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Dave Smith Defenses to 1NT Brogeland, Del Monte New partners take Ask a group of capture IMP Pairs Women’s Pairs experts about their favorite methods of Irina Ladyzhensky and Kamla Chawla, who competing when an had never played in person before the Whitehead opponent opens a Women’s Pairs, parlayed a 65% game in the first strong 1NT (15— final session to victory in the event. It was the first 17), and you will North American championship for each. receive a variety of They finished just ahead of Valerie Westheimer answers. The Daily and Migry Zur-Campanile. Bulletin has featured Ladyzhensky is a math teacher in Ellenton FL, one method each day Continued on page 7 during the NABC. Boye Brogeland and Ishmael Delmonte. Note: Players should be aware that several of Boye Brogeland and Ishmael Delmonte, who the systems described in this series use Mid-Chart play together only at NABCs, are used to leading conventions and are not permited in events that in the late stages of ACBL pairs events, but until are restricted to the General Convention Chart. Friday they had not had the experience of The director in charge can provide the information winning. you need. That changed when they had a monster first Today’s expert is Jerry Helms from Charlotte final session in the Lebhar IMP Pairs and won the NC. event going away, more than 17 IMPs ahead of the Helms, like many top players, loves to runners-up, Jonathan Weinstein of Evanston IL compete over the opponents’ opening 1NT. -

Lucire August 2004 on the Web Read the Full Story and Reviews At

Gabriel Scarvelli One designer can change the world august 2004 American idol The true idol look A light exists in spring Bronzing The gap Regardless of the between seasons season The circuit Cocktails Hot o\ the in London catwalks at The trendiest Sydney, Toronto, Los Angeles, Miami bars in town Hilary Permanent Rowland make-up Model We expose the businesswoman dangers juicy style 0 8 GST The global fashion magazine | www.lucire.com incl. http://lucire.com 1175-7515 1 $9·45 NZ ISSN 9 7 7 1 1 7 5 5 7 5 1 0 0 FASHION THE CIRCUIT Australian teenager Abbey Lee, 16, pictured here at the Lisa Ho (right) and Willow (above) shows made her modelling debut at Mercedes Australian Fashion Week 2004. Until then she had never worn make- up or high heels, yet she not only carried off the whole week with aplomb, but dealt with a broken heel at the Sunjoo Moon show without so much as a wobble. above left: One Teaspoon staged a lavish “Alannah Hill rip-off- style show” to promote its tank tops and tiny frocks. above: Surprise of the week: Wayne Cooper took his inspiration from ’50s Hollywood, while the Beckhams’ hairdresser Tyler Johnson for Schwarzkopf did the coiffs. above right and right: It seems the waistline is rising according to many designers, including Jayson Brunsdon. left: Sass in Bide dominated the front papers of the Sydney dailies with an unofficial off-schedule show the day before MAFW. Not the way of all flesh Gwendolynne designer Gwendolynne Burkin obviously had a hard time trying to edit her favourite Fortunately, enough of the local designers steered clear of “tits garments, staging an hour-long show. -

OHAA QLD Newsletter, December 2002 (Brisbane State Conference)

December 2002 Editor: Suzanne Mulligan 17 Pallinup Street approach to presenting an oral history RIVERHILLS QLD 4074 project in DVD format. Elisabeth Gondwe Email: [email protected] and Tracy Ryan gave a delightful presentation on their North Stradbroke Seasons Greetings Fellow Members! Island Oral History Project which involves the whole community. Dr Greg Mallory The last few months have been very busy discussed his views on Brisbane rugby for our committee, particularly for league’s decline mirrored by the decline in Secretary, Lesley Jenkins, as she organised local community spirit. Norman Sheridan our State Conference held at the State gave a presentation on Institution of Library on 16-17 November 2002. Engineers’ project. Kay Cohen asked Congratulations to Lesley on a very whether there was a difference between successful conference! interviewing powerful people and “ordinary” people. Leith Barter presented More than 50 people attended our a very interesting paper/video on his conference which was formally opened by ongoing Pine Rivers project where an State Librarian Lea Giles-Peters who enlightened Council has recognised the introduced our keynote speaker, Robin value of oral history in documenting the Hughes. Robin gave a fascinating and history of that area. Margaret Klaassen informative presentation. She was a very entertained us with a challenge to improve approachable and easy-going person who our voice quality to make our interviewing was happy to field questions and share her more effective. experiences throughout the weekend. All who attended her presentation and This newsletter contains most of the papers workshop greatly benefited from the presented at the conference or summaries obvious passion she has for her craft. -

J. R Kemp, the "Grand Pooh-Bah"

THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Accepte—r-—d fo,wr, thi,,ce dwarawarda OoTf ^<^-^^-..<?L/i/^fi.i J. R KEMP, on.TH' E "GRAND POOH-BAH": A STUDY OF TECHNOCRACY AND STATE DEVELOPMENT IN QUEENSLAND, 1920 -1955 A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Queensland Kay Cohen B. A.(Fr.),B. Soc.Stud.,M.A(Govt.) School of Political Science and International Studies University of Queensland Brisbane, Queensland March 2002 Statement of Originality The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and behef, original, except as acknowledged in the text. The material has not been submitted in whole or in part for a degree at this or any other University. Kay Teresa Cohen March, 2002 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to many colleagues and friends for their patience and helpful advice during the long process of writing this thesis. Thanks also to the staff and members of various archives, Ubraries and associations for vviiom no request of mine was too much trouble, and departmental support staff and post-graduate students who were always cheerfully supportive. I owe a great deal to my supervisor. Dr. Paul Reynolds, for helping me realise a long- held ambition. His reassurances kept me going when I might have given in and given up. Finally, to my family, Jon, Samantha, Ben, Toby and Sally, I will always be grateful for your constant encouragement and loving support through what were difficult times for all of us. J. R. KEMP, THE "GRAND POOH-BAH": A STUDY OF TECHNOCRACY AND STATE DEVELOPMENT IN QUEENSLAND, 1920 -1955. -

Fade to Black

BRIDGET INDIA IN FASHION FOLEY’S Lakme Fashion Week saw a slew of new designers on DIARY: the runways as the market continues to soar. PAGE 8 The Case for Marc at Dior. PAGE 12 THE B-T-S UNIFORM Denim Sales Surge On Price Cuts, Color By ARNOLD J. KARR DENIM IS BATTLING the calendar, the economy and the rest of fashion to maintain its status as teen- agers’ favorite back-to-school wear. And thanks in part to aggressive price promotions, it ap- WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 24, 2011 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 pears to be winning as b-t-s selling enters its home stretch. The b-t-s season got off to a strong start before hit- WWD ting a bit of a midsummer lull and jeans sales, a criti- cal component of the season, generally have followed suit. While the remaining b-t-s dollars are being held onto tightly by cautious consumers, colored denim has continued to show notable strength, in many cases outstripping relatively modest supplies, and skinny and even skin-tight silhouettes, often in stretch denim, are quickly gaining favor with female teens and young adults. Retailers, vendors and ana- lysts have also reported positive reactions to darker washes and cropped-bottom jeans but were less en- thusiastic about fl ared-bottom models. Despite price increases brought on by the higher cost of cotton, jeans continue to serve as an impor- Fade tant promotional lure for stores. Observers give Abercrombie & Fitch Co. high marks for the “reen- gineering” of its denim assortment to incorporate different fi ts, silhouettes and fabrics, but just as im- portant to the recent success of its jeans offering has been its aggressive pricing policy, at both the fl agship To and Hollister divisions, which in many cases has seen prices cut by 50 percent. -

Loreto Reunions

Print Post Approved No. PP 451 207/00 220 ChronicleLoreto Volume 28 No.2 December 2014 From the Principal This Chronicle brings news n a beautiful afternoon in October, of the retirement of five much OOpeningLoreto connections past andof present ‘Cruci’ loved, long standing members gathered for the opening and blessing of staff who between them of Cruci, our striking new building at the have given 142 years of Cavendish Road entrance to the College. loyal and committed service Cruci was opened by to Loreto College. Each of Margaret Mary Flynn ibvm, Loreto Province Leader, these fine educators has and blessed by Fr Paul contributed greatly to the Sireh, Mt Carmel Parish education of thousands of young women Priest. The name Cruci in the Mary Ward tradition. At year’s means Cross and is a (L-R) Mrs Diane Bukowski - Chair of Council, end, the students and staff took great reference to the Loreto motto ‘Cruci dum Margaret Mary Flynn ibvm, Fr Paul Sireh delight in awarding each of them “Honour spiro fido’ which translates as ‘While I live Pockets” in recognition of their outstanding I trust in the Cross’. This central symbol of commitment, generous service and Christianity is incorporated in the design of the building with a cross clearly visible leadership. Their Honour Pockets along in the wall facing onto Cavendish Road. with the year each one began teaching at The name Cruci is also a reference to Loreto are as follows: what has become the College hymn, • Dr Raimund Irmer (1983) – Academic ‘Cruci dum Spiro Fido’, written by Excellence & Service to Science Deirde Browne ibvm while she was Community Leader at Coorparoo. -

How a Reddit Army Brought an Australian Lingerie Icon Back from the Dead

Advertisement Investigation Companies Retail Mergers & acquisitions How a Reddit army brought an Australian lingerie icon back from the dead Elle Macpherson in 1998 with models dressed in her eponymous underwear range. Her break with Bendon in 2014 marked the start of the company’s financial woes. CarrieCarrieCarrie LaF LaFLaFrenzrenzrenz and JJJesesessicasicasica Sier SierSier Jul 2, 2021 – 11.16am emperatures were near freezing in January and the strict COVID-19 T lockdowns in Anna’s European hometown meant the 30-something retail investor was spending hours glued to her screens. Anna works in education by day but often spends extra hours searching for penny stocks worth betting on. In the days after Christmas her screen, and those of countless others around the globe, had started to hum with activity. A movement of retail traders was coalescing around the idea that money could be made from taking down Wall Street hedge funds. All they needed to do was pile into some of the worst companies on the market in sufficient numbers that the short-selling hedge funds would be caught out. American video game retailer GameStopGameStopGameStop and theatre chain AMCAMCAMC EntertainmentEntertainmentEntertainment were the early movers, and within days traders on Reddit forums like r/wallstreetbets were reporting tidy profits as share prices began to climb. Chairman of Naked Brand Group Justin Davis-Rice. Rhett Wyman Anna was looking for the next big thing when she noticed one little-known stock being mentioned more often. Redditors were posting excitedly about the possibility of sending Naked Brand (NAKD) shares “to the moon” and “making the hedge funds cry”. -

Issue No. 864 | July 2021

________________________________________________________________________________________________________ - THE RHSQ Bulletin 79 years of continuous publication JULY 2021 No. 864 The newsletter of The Royal Historical Society of Queensland Patron: His Excellency the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Governor of Queensland President: Dr Denver Beanland AM Website: www.queenslandhistory.org ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ HENRY MARJORIBANKS CHESTER QUEENSLAND PIONEER RHSQ Photo Collection PD – 25 Henry Majoribanks Chester was born in London in 1832. He saw service in the Indian navy, including actions against pirates in the Persian Gulf, followed by a period as political agent to the court of Oman. In ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The RHSQ Bulletin, July 2021 – Page 2 1862, he migrated to Queensland. He held various positions in the then Department of Public Lands, and acted briefly as police magistrate for the Cape York town of Somerset. Between 1875 and 1903 he was appointed police magistrate at a number of remote and often ‘troublesome’ settlements. He returned to Somerset in this role in 1875, moving his headquarters to Thursday Island in 1877. He became a notable figure when the Queensland Premier, perceiving a threat from German expansionist intentions, asked him to take possession of unoccupied eastern New Guinea, in Queensland’s name. This annexation was not recognised by the British government until 1884. Chester retired in 1903 and died in Brisbane in 1914. (Ref: G. Bolton, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 3, (MUP), 1969). The RHSQ Library Archives holds the H M Chester collection which includes letters, diaries and certificates. President’s Report Your Society will be undertaking a major Book Fair, between the hours of 10.00 am and 3.00 pm, at the Commissariat Store, 115 William Street, City, on Saturday 14 August for Society members.