Section 6 Potato (Solanum Tuberosum Subsp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

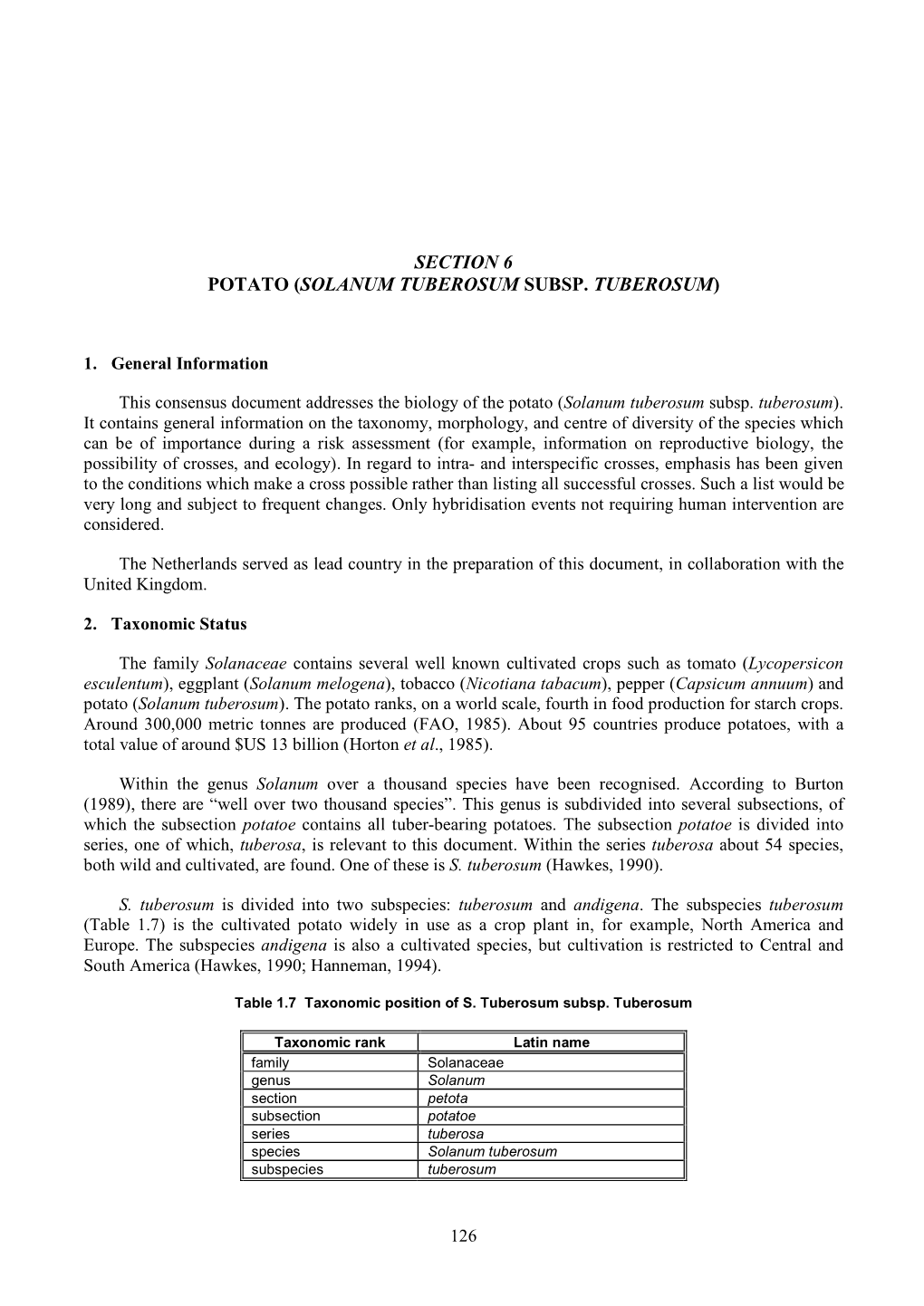

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition AKA exotic, alien, non-native, introduced, non-indigenous, or foreign sp. National Invasive Species Council definition: (1) “a non-native (alien) to the ecosystem” (2) “a species likely to cause economic or harm to human health or environment” Not all invasive species are foreign origin (Spartina, bullfrog) Not all foreign species are invasive (Most US ag species are not native) Definition increasingly includes exotic diseases (West Nile virus, anthrax etc.) Can include genetically modified/ engineered and transgenic organisms Executive Order 13112 (1999) Directed Federal agencies to make IS a priority, and: “Identify any actions which could affect the status of invasive species; use their respective programs & authorities to prevent introductions; detect & respond rapidly to invasions; monitor populations restore native species & habitats in invaded ecosystems conduct research; and promote public education.” Not authorize, fund, or carry out actions that cause/promote IS intro/spread Political, Social, Habitat, Ecological, Environmental, Economic, Health, Trade & Commerce, & Climate Change Considerations Historical Perspective Native Americans – Early explorers – Plant explorers in Europe Pioneers moving across the US Food - Plants – Stored products – Crops – renegade seed Animals – Insects – ants, slugs Travelers – gardeners exchanging plants with friends Invasive Species… …can also be moved by • Household goods • Vehicles -

The Natural History of Reproduction in Solanum and Lycianthes (Solanaceae) in a Subtropical Moist Forest

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 11-28-2002 The Natural History of Reproduction in Solanum and Lycianthes (Solanaceae) in a Subtropical Moist Forest Stacey DeWitt Smith University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Sandra Knapp Natural History Museum, London Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub Part of the Life Sciences Commons Smith, Stacey DeWitt and Knapp, Sandra, "The Natural History of Reproduction in Solanum and Lycianthes (Solanaceae) in a Subtropical Moist Forest" (2002). Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences. 104. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub/104 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Bull. nat. Hist. Mus. Lond. (Bot.) 32(2): 125–136 Issued 28 November 2002 The natural history of reproduction in Solanum and Lycianthes (Solanaceae) in a subtropical moist forest STACEY D. SMITH Department of Botany, 132 Birge Hall, 430 Lincoln Drive, University of Wisconsin, Madison WI 53706-1381, U.S.A. SANDRA KNAPP Department of Botany, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................ -

Of Physalis Longifolia in the U.S

The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review1 ,2 3 2 2 KELLY KINDSCHER* ,QUINN LONG ,STEVE CORBETT ,KIRSTEN BOSNAK , 2 4 5 HILLARY LORING ,MARK COHEN , AND BARBARA N. TIMMERMANN 2Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA 4Department of Surgery, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA 5Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review. The wild tomatillo, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related species have been important wild-harvested foods and medicinal plants. This paper reviews their traditional use as food and medicine; it also discusses taxonomic difficulties and provides information on recent medicinal chemistry discoveries within this and related species. Subtle morphological differences recognized by taxonomists to distinguish this species from closely related taxa can be confusing to botanists and ethnobotanists, and many of these differences are not considered to be important by indigenous people. Therefore, the food and medicinal uses reported here include information for P. longifolia, as well as uses for several related taxa found north of Mexico. The importance of wild Physalis species as food is reported by many tribes, and its long history of use is evidenced by frequent discovery in archaeological sites. These plants may have been cultivated, or “tended,” by Pueblo farmers and other tribes. The importance of this plant as medicine is made evident through its historical ethnobotanical use, information in recent literature on Physalis species pharmacology, and our Native Medicinal Plant Research Program’s recent discovery of 14 new natural products, some of which have potent anti-cancer activity. -

Nightshade”—A Hierarchical Classification Approach to T Identification of Hallucinogenic Solanaceae Spp

Talanta 204 (2019) 739–746 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Talanta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/talanta Call it a “nightshade”—A hierarchical classification approach to T identification of hallucinogenic Solanaceae spp. using DART-HRMS-derived chemical signatures ∗ Samira Beyramysoltan, Nana-Hawwa Abdul-Rahman, Rabi A. Musah Department of Chemistry, State University of New York at Albany, 1400 Washington Ave, Albany, NY, 12222, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Plants that produce atropine and scopolamine fall under several genera within the nightshade family. Both Hierarchical classification atropine and scopolamine are used clinically, but they are also important in a forensics context because they are Psychoactive plants abused recreationally for their psychoactive properties. The accurate species attribution of these plants, which Seed species identifiction are related taxonomically, and which all contain the same characteristic biomarkers, is a challenging problem in Metabolome profiling both forensics and horticulture, as the plants are not only mind-altering, but are also important in landscaping as Direct analysis in real time-mass spectrometry ornamentals. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry in combination with a hierarchical classification workflow Chemometrics is shown to enable species identification of these plants. The hierarchical classification simplifies the classifi- cation problem to primarily consider the subset of models that account for the hierarchy taxonomy, instead of having it be based on discrimination between species using a single flat classification model. Accordingly, the seeds of 24 nightshade plant species spanning 5 genera (i.e. Atropa, Brugmansia, Datura, Hyocyamus and Mandragora), were analyzed by direct analysis in real time-high resolution mass spectrometry (DART-HRMS) with minimal sample preparation required. -

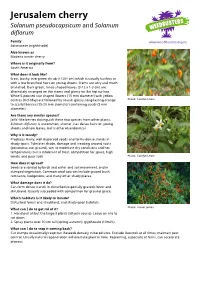

Solanum Pseudocapsicum

Solanum pseudocapsicum COMMON NAME Jerusalem cherry FAMILY Solanaceae AUTHORITY Solanum pseudocapsicum L. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE SOLPSE HABITAT Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. Terrestrial. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe FEATURES Erect, unarmed shrub, glabrous or sometimes with few branched hairs on very young shoots; stems wiry, 40~120cm tall. Petiole to 2cm long, slender. Lamina 3~12 x 1~3cm, lanceolate or elliptic-lanceolate, glossy above; margins usu. undulate; base narrowly attenuate; apex obtuse or acute. Flowers 1~several; peduncle 0~8mm long; pedicels 5~10mm long, erect at fruiting. Calyx 4~5mm long; lobes lanceolate to ovate, slightly accrescent. Corolla approx. 15mm diam., white, glabrous; lobes oblong- ovate to triangular. Anthers 2.5~3mm long. Berry 1.5~2cm diam., globose, glossy, orange to scarlet, long-persistent; stone cells 0. Seeds approx. Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. 3mm diam., suborbicular to reniform or obovoid, rather asymmetric; Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe margin thickened. (-Webb et. al., 1988) SIMILAR TAXA A plant with attractive glossy orange or red berries around 1-2 cm diameter (Department of Conservation 1996). FLOWERING October, November, December, January, February, March, April, May FLOWER COLOURS White, Yellow YEAR NATURALISED 1935 ORIGIN Eastern Sth America ETYMOLOGY solanum: Derivation uncertain - possibly from the Latin word sol, meaning “sun,” referring to its status as a plant of the sun. Another possibility is that the root was solare, meaning “to soothe,” or solamen, meaning “a comfort,” which would refer to the soothing effects of the plant upon ingestion. Reason For Introduction Ornamental Life Cycle Comments Perennial. Dispersal Seed is bird dispersed (Webb et al., 1988; Department of Conservation 1996). -

Morphological and Physiological Correlations in the Solanaceae David

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1923 Morphological and physiological correlations in the solanaceae David. Potter University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Potter, David., "Morphological and physiological correlations in the solanaceae" (1923). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1888. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1888 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASSACHUSETTS STATE COLLEGE I IRR ARV MORRILL LD 3234 iVi268 1923 P8664 MORPHOLOGICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL CORRELATIONS IN THE SOLANACEAE DaTid Potter Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Haster of Science Massachusetts Agricultural College Amherst, Mass. June 1923 ACHSrOWLEDGHENTS The writer wishes to express his sincere appreciation of the never failing kindness and assis- tance of all the members of the Department of Botany of the Massachusetts Agricultural College. Particular thanks are due to Miss Gladys I. Miner and Miss Anna M. Wallace for their help in typing and proof-reading; to Doctor W. H. Davis for his advice in the photographic work: to Professor 0. L. Clark for his helpful suggestions and criticisms of the physiological work and to Professor A. V. Osmun for his much valued assistance. Above all is the writer indebted to Doctor H. &• Torrey who has ever been an inspiration and through his helpful guidance has made this work possible. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 I. -

Biogeografía De Lycianthes (Capsiceae, Solanaceae) En México Maestro En Ciencias En Biosistemática Y Manejo De Recursos Natur

UNIVERSIDAD DE GUADALAJARA Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias Biogeografía de Lycianthes (Capsiceae, Solanaceae) en México Tesis Tesis que para obtener el grado de Maestro en Ciencias en Biosistemática y Manejo de Recursos Naturales y Agrícolas Presenta Marco Antonio Anguiano Constante Zapopan, Jalisco Noviembre de 2019 UNIVERSIDAD DE GUADALAJARA Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias Biogeografía de Lycianthes (Capsiceae, Solanaceae) en México Tesis que para obtener el grado de Maestro en Ciencias en Biosistemática y Manejo de Recursos Naturales y Agrícolas Presenta Marco Antonio Anguiano Constante Directora Guadalupe Munguía Lino Asesores María del Pilar Zamora Tavares Aarón Rodríguez Contreras Eduardo Ruiz Sánchez Zapopan, Jalisco Noviembre de 2019 In memoriam Miriam Anguiano Constante † Agradecimientos Agradezco al Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) por la beca de manutención número 855486/631102 y la beca de movilidad número 291250. A la Universidad de Guadalajara por permitirme realizar mis estudios de posgrado. A Guadalupe Munguía Lino por aceptar dirigir este trabajo y ser parte primordial durante mi carrera académica. A Aarón Rodríguez por guiarme durante mis estudios. La pasión que demuestras día a día en el herbario inspira. A mi comité conformado por Aarón Rodríguez, Eduardo Ruiz Sánchez, Pilar Zamora Tavares y Jessica Pérez Alquicira por dedicar tiempo para llevar a buen término esta responsabilidad. A mis profesores, especialmente a Dánae Cabrera Toledo, Mollie Harker, Ofelia Vargas Ponce, Jessica Pérez Alquicira, Gina Vargas Amado, Eduardo Ruiz Sánchez, Pablo Carrillo Reyes, Daniel Sánchez Carbajal y Miguel Muñiz Castro por trasmitir sus conocimientos. A Patricia Zarazúa Villaseñor por su desempeño como coordinadora y el resto del personal del programa de Maestría en Ciencias en Biosistemática y Manejo de Recursos Naturales y Agrícolas (BIMARENA). -

Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity

Natural Products Chemistry & Research Review Article Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity Morillo M1, Rojas J1, Lequart V2, Lamarti A 3 , Martin P2* 1Faculty of Pharmacy and Bioanalysis, Research Institute, University of Los Andes, Mérida P.C. 5101, Venezuela; 2University Artois, UniLasalle, Unité Transformations & Agroressources – ULR7519, F-62408 Béthune, France; 3Laboratory of Plant Biotechnology, Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tetouan, Morocco ABSTRACT Steroidal alkaloids are secondary metabolites mainly isolated from species of Solanaceae and Liliaceae families that occurs mostly as glycoalkaloids. α-chaconine, α-solanine, solamargine and solasonine are among the steroidal glycoalkaloids commonly isolated from Solanum species. A number of investigations have demonstrated that steroidal glycoalkaloids exhibit a variety of biological and pharmacological activities such as antitumor, teratogenic, antifungal, antiviral, among others. However, these are toxic to many organisms and are generally considered to be defensive allelochemicals. To date, over 200 alkaloids have been isolated from many Solanum species, all of these possess the C27 cholestane skeleton and have been divided into five structural types; solanidine, spirosolanes, solacongestidine, solanocapsine, and jurbidine. In this regard, the steroidal C27 solasodine type alkaloids are considered as significant target of synthetic derivatives and have been investigated -

Jerusalem Cherry Solanum Pseudocapsicum and Solanum Diflorum

Jerusalem cherry Solanum pseudocapsicum and Solanum diflorum Family Solanaceae (nightshade) Also known as Madeira winter cherry Where is it originally from? South America What does it look like? Erect, bushy, evergreen shrub (<120+ cm) which is usually hairless or with a few branched hairs on young shoots. Stems are wiry and much branched. Dark green, lance-shaped leaves (3-12 x 1-3 cm) are alternately arranged on the stems and glossy on the top surface. White 5-pointed star shaped flowers (15 mm diameter) with yellow centres (Oct-May) are followed by round, glossy, long-lasting orange Photo: Carolyn Lewis to scarlet berries (15-20 mm diameter) containing seeds (3 mm diameter). Are there any similar species? Jaffa'-like berries distinguish these two species from other plants. Solanum diflorum is uncommon, shorter, has dense hairs on young shoots and new leaves, but is otherwise identical. Why is it weedy? Produces many, well dispersed seeds and forms dense stands in shady spots. Tolerates shade, damage and treading around roots (poisonous, not grazed), wet to moderate dry conditions and hot temperatures but is intolerant of frost, competition for space, high winds, and poor soils. Photo: Carolyn Lewis How does it spread? Seeds are spread by birds and water and soil movement, and in dumped vegetation. Common seed sources include grazed bush remnants, hedgerows, and many other shady places. What damage does it do? Can form dense stands in disturbed (especially grazed) forest and shrubland. Usually succeeded with competition for ground space. Which habitats is it likely to invade? Disturbed forest and shrubland, and shady open habitats. -

Pollen Release Mechanisms and Androecium Structure in Solanum

Flora 224 (2016) 211–217 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Flora journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/flora Pollen release mechanisms and androecium structure in Solanum (Solanaceae): Does anther morphology predict pollination strategy? ∗ Bruno Fernandes Falcão , Clemens Schlindwein, João Renato Stehmann Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Departamento de Botânica, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, Caixa Postal 486, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, CEP 31270-901, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Most species of Solanum L. (Solanaceae) exhibit a floral morphology typical of the genus: Yellow poricidal Received 18 November 2015 anthers with rigid walls contrasting in color with the corolla. However, some species of Solanum sect. Received in revised form 22 July 2016 Cyphomandropsis differ from most of the other species of Solanum by having flowers without contrast- Accepted 4 August 2016 ing colors and large anthers with flexible walls. These features resemble those of some closely related Edited by Stefan Dötterl species belonging to Solanum sect. Pachyphylla that exhibit a bellows pollination mechanism whereby Available online 28 August 2016 male euglossine bees cause the compression of thin anther walls and trigger pneumatic pollen release without vibration. Herein we studied the reproductive and pollination biology of a population of Solanum Keywords: luridifuscescens (sect. Cyphomandropsis), a species with purple corolla and anthers, expecting to find a Atlantic forest Cyphomandropsis bellows mechanism of pollination. Both artificial mechanical stimuli applied with forceps and vibrations Buzz-pollination transmitted with an electric toothbrush resulted in the release of pollen from the anthers. -

An Introduction to Pepino (Solanum Muricatum Aiton)

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-1, Issue-2, July -Aug- 2016] ISSN: 2456-1878 An introduction to Pepino ( Solanum muricatum Aiton): Review S. K. Mahato, S. Gurung, S. Chakravarty, B. Chhetri, T. Khawas Regional Research Station (Hill Zone), Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India Abstract — During the past few decades there has been America, Morocco, Spain, Israel and the highlands of renewed interest in pepino cultivation both in the Andean Kenya, as the pepino is considered a crop with potential for region and in several other countries, as the pepino is diversification of horticultural production (Munoz et al, considered a crop with potential for diversification of 2014). In the United States the fruit is known to have been horticultural production. grown in San Diego before 1889 and in Santa Barbara by It a species of evergreen shrub and vegetative propagated 1897 but now a days, several hundred hectares of the fruit by stem cuttings and esteemed for its edible fruit. Fruits are are grown on a small scale in Hawaii and California. The juicy, scented, mild sweet and colour may be white, cream, plant is grown primarily in Chile, New yellow, maroon, or purplish, sometimes with purple stripes Zealand and Western Australia. In Chile, more than 400 at maturity, whilst the shape may be spherical, conical, hectares are planted in the Longotoma Valley with an heart-shaped or horn-shaped. Apart from its attractive increasing proportion of the harvest being exported. morphological features, the pepino fruit has been attributed Recently, the pepino has been common in markets antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and in Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Chile and grown antitumoral activities. -

Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa Decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives

insects Review Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives Martina Kadoi´cBalaško 1,* , Katarina M. Mikac 2 , Renata Bažok 1 and Darija Lemic 1 1 Department of Agricultural Zoology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.L.) 2 Centre for Sustainable Ecosystem Solutions, School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health, University of Wollongong, Wollongong 2522, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-239-3654 Received: 8 July 2020; Accepted: 22 August 2020; Published: 1 September 2020 Simple Summary: The Colorado potato beetle (CPB) is one of the most important potato pest worldwide. It is native to U.S. but during the 20th century it has dispersed through Europe, Asia and western China. It continues to expand in an east and southeast direction. Damages are caused by larvae and adults. Their feeding on potato plant leaves can cause complete defoliation and lead to a large yield loss. After the long period of using only chemical control measures, the emergence of resistance increased and some new and different methods come to the fore. The main focus of this review is on new approaches to the old CPB control problem. We describe the use of Bacillus thuringiensis and RNA interference (RNAi) as possible solutions for the future in CPB management. RNAi has proven successful in controlling many pests and shows great potential for CPB control. Better understanding of the mechanisms that affect efficiency will enable the development of this technology and boost potential of RNAi to become part of integrated plant protection in the future.