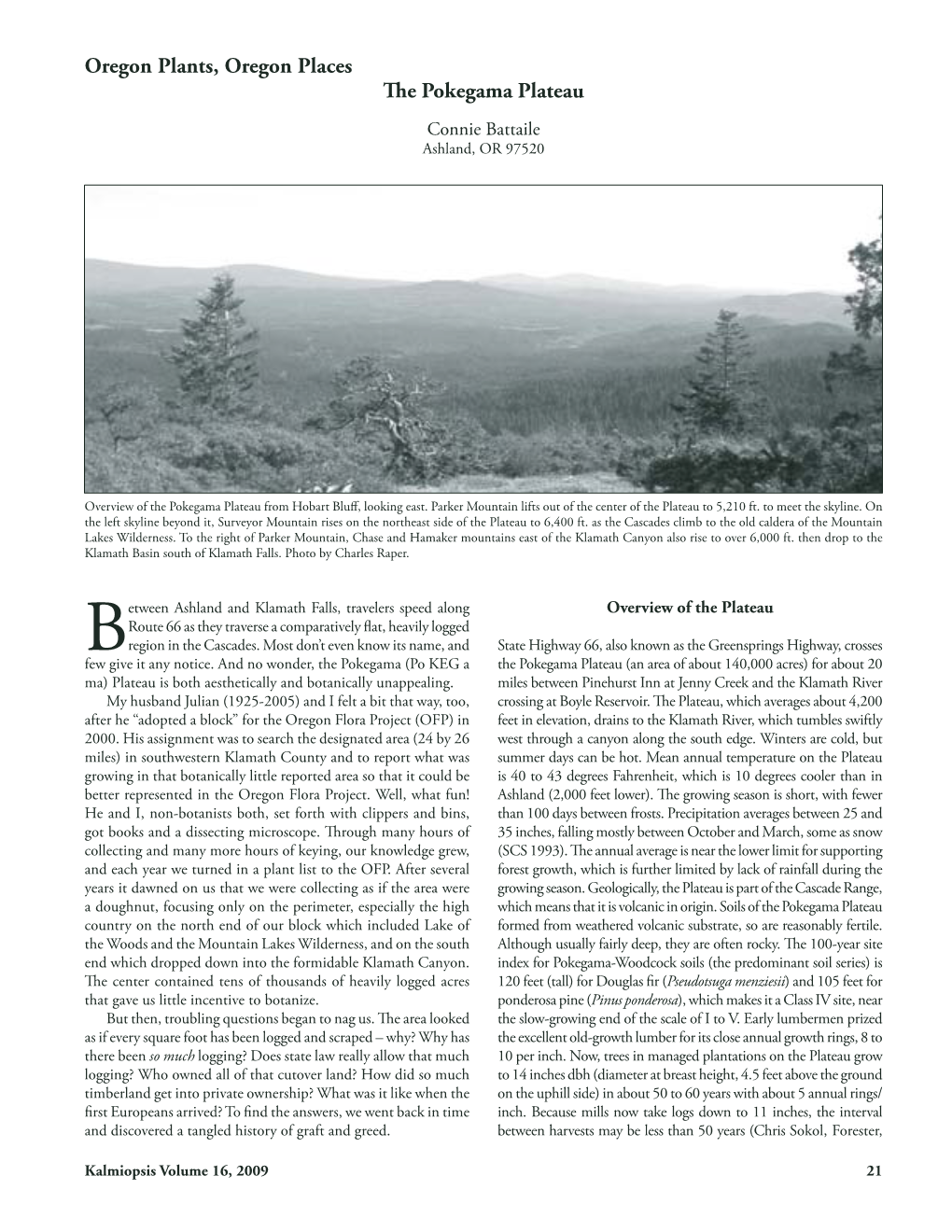

The Pokegama Plateau from Hobart Bluff , Looking East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perilous Last Leg of the Oregon Trail Down the Columbia River

Emigrant Lake County Park California National Historic Trail Hugo Neighborhood Association and Historical Society Jackson County Parks National Park Service The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon The perilous last leg of the Oregon Trail down the “Father and Uncle Jesse, seeing their children drowning, were seized with ‘ Columbia River rapids took lives, including the sons frenzy, and dropping their oars, sprang from their seats and were about to make a desperate attempt to swim to them. But Mother and Aunt Cynthia of Jesse and Lindsay Applegate in 1843. The Applegate cried out, ‘Men, don't quit your oars! If you do, we'll all be lost!’” brothers along with others vowed to look for an all- -Lindsay Applegate’s son Jesse land route into Oregon from Idaho for future settlers. “Our hearts are broken. As soon as our families are settled and time can be spared we must look for another way that avoids the river.” -Lindsay Applegate In 1846 Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and 13 others from near Dallas, Oregon, headed south following old trapper trails into a remote region of Oregon Country. An Umpqua Indian showed them a foot trail that crossed the Calapooya Mountains, then on to Umpqua Valley, Canyon Creek, and the Rogue Valley. They next turned east and went over the Cascade Mountains to the Klamath Basin. The party devised pathways through canyons and mountain passes, connecting the trail south from the Willamette Valley with the existing California Trail to Fort Hall, Idaho. In August 1846, the first emigrants to trek the new southern road left Fort Hall. -

1 Applegate Emigrants to Oregon in 1843

http://www.oregonpioneers.com/1843.htm 1 Applegate Emigrants to Oregon In 1843 Albert APPLEGATE was actually born in the Oregon Territory December 6, 1843 at the abandoned Willamette Mission where his parents, Charles Applegate and Melinda Miller, wintered. While not enumerated as an emigrant of that year he can certainly be considered a pioneer of that time period. Albert married January 17, 1869 at Drain, Douglas County, Oregon to Nancy Johnson. His adult years were spent in the Douglas Co area. It was here that he raised his family: Mercy D. (1870), Nellie M. (1871), Jesse Grant (1873), Fred (1875) and Lulu (1878). Albert died March 18, 1888. After his death his wife, Nancy Johnson Applegate, married James Shelley and was residing at Eugene, Lane County, Oregon in the 1900 census. Alexander McClelland APPLEGATE was born Mar 11, 1838 in St. Clair County, Missouri, the son of Jesse Applegate and Cynthia Parker. He was five years old at the time the Applegates crossed the plains to Oregon in 1843. With his family he settled in Polk County in 1844 and in 1850 was living in Benton County. By 1860 the family had moved to Yoncalla, Douglas County, OR. Shortly after arriving, Alex went to the Idaho gold fields with Henry Lane, son of the famous Joseph Lane, who lived in nearby Roseburg. He and Henry and Alex's cousin John Applegate enjoyed playing the fiddle together. They often played at dances as "The Fiddlers Three." Henry Lane had been a suitor of Alex’s cousin, Harriet. When the young men received the news in Idaho of the death of Harriet Applegate, Alex wrote home: "Your dream that some of us who parted last spring would no longer meet again in this life has been fulfilled. -

THE SIGNERS of the OREGON MEMORIAL of 1838 the Present Year, 1933, Is One of Unrest and Anxiety

THE SIGNERS OF THE OREGON MEMORIAL OF 1838 The present year, 1933, is one of unrest and anxiety. But a period of economic crisis is not a new experience in the history of our nation. The year 1837 marked the beginning of a real panic which, with its after-effects lasted well into 1844. This panic of 1837 created a restless population. Small wonder, then, that an appeal for an American Oregon from a handful of American settlers in a little log mission-house, on the banks of the distant Willamette River, should have cast its spell over the depression-striken residents of the Middle Western and Eastern sections of the United States. The Memorial itself, the events which led to its inception, and the detailed story o~ how it was carried across a vast contin ent by the pioneer Methodist missioinary, Jason Lee, have already been published by the present writer.* An article entitled The Oregon Memorial of 1838" in the Oregon Historical Quarterly for March, 1933, also by the writer, constitutes the first docu mented study of the Memorial. Present-day citizens of the "New Oregon" will continue to have an abiding interest in the life stories of the rugged men who signed this historiq first settlers' petition in the gray dawn of Old Oregon's history. The following article represents the first attempt to present formal biographical sketches of the thirty-six signers of this pioneer document. The signers of the Oregon Memorial of 1838 belonged to three distinct groups who resided in the Upper Willamette Valley and whose American headquarters were the Methodist Mission house. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Grandma Rock Emigrants

Manzanita Rest Area California National Historic Trail Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians National Park Service Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Hugo Neighborhood Association Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians and Historical Society The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon The perilous last leg of the Oregon Trail down the ‘ Columbia River rapids took lives, including the sons of Jesse and Lindsay Applegate in 1843. The Applegate brothers and others vowed to look for an all-land route into Oregon from Fort Hall (in present-day Idaho) for future settlers. Additionally, It was important to have a way by such we could leave the country without running the gauntlet of the Hudson’s Bay Co.’s forts and falling prey to Indians which were under British influence. -Lindsay Applegate In 1846 Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and 13 others Father and Uncle Jesse, seeing their children from near Dallas, Oregon, headed south following old drowning, were seized with frenzy, and dropping their oars, sprang from their seats trapper trails into a remote region of Oregon Country. and were about to make a desperate attempt First they crossed the Calapooya Mountains, then the to swim to them. But Mother and Aunt Cynthia Umpqua Valley, Canyon Creek, and the Rogue Valley. cried out, ‘Men, don't quit your oars! If you do, we'll all be lost!’ They next turned east and went over the Cascade -Lindsay Applegate’s son Jesse Mountains to the lakes of the Klamath Basin. The party detoured around the lakes and located the Our hearts are broken. -

Sucentenji REV

suCENTENjI REV. A. F.VALLER. 1q84. 4( 4 >)) 1834. A TEN NIAL toTIlE 1\4EMI3ERS AND FRIENDS OF TIIR Methodist Episcopal Church, SALEN'L. OREGON. NIRS. \V. H. ODELL. "Hitherto the Lord hat/i helped US." INTRODUCTION. HE year of grace A.D. l8S-, was not only the Centennialyear of the Methodist Episcopal Church, but the semi-centennial of the work of the same church in Oregon. In the year 1834 Jason Lee organized, near where the city of Salem now stands, the first Protestant mission west of the Rockies. The WillametteUniversity and the church in Salem are twin children of that mission.Like Chang and Eng their lives are inseparable. In that centennial, and semi-centennial, period, after a struggle of many years, as narrated in these pages, the Salem M. E. Church became free from debt.The writer of this "Introduction" being at that time pastor thereof, found hiniself making this inquiry: How can we best set up a memorial of this glad consummation, which shall at once express our gratitude to Him who has brought deliver- ance to our Israel, and also keep the memory thereof fresh in the minds of our children and successors? This little volume is sent out as a suitable answer to that question. In casting about to find some one who could be safely entrusted with its preparation, my thought turned toward Mrs. Gen. W. H. Odell, who reluctantly but kindly consented to undertake the task. This accomplished lady whose former husband, Hon. Samuel R. Thurston, was the first delegate to Congress from the Territory of Oregon, and who herself was early, and for some time, a teacher in the "Oregon Institute," as the Willamette University was then called, brought rare qualifications to this undertaking.Jier work which has been done con am ore, will be useful long after she has entered the pearly gates. -

The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon ‘

Emigrant Lake County Park California National Historic Trail Hugo Neighborhood Association and Historical Society Jackson County Parks National Park Service The 1846 Applegate Trail—Southern Route to Oregon ‘ The perilous last leg of the Oregon Trail down the “Father and Uncle Jesse, seeing their children drowning, were seized with Columbia River rapids took lives, including the sons frenzy, and dropping their oars, sprang from their seats and were about to make a desperate attempt to swim to them. But Mother and Aunt Cynthia of Jesse and Lindsay Applegate in 1843. The Applegate cried out, ‘Men, don't quit your oars! If you do, we'll all be lost!’” brothers along with others vowed to look for an all- -Lindsay Applegate’s son Jesse land route into Oregon from Idaho for future settlers. “Our hearts are broken. As soon as our families are settled and time can be spared we must look for another way that avoids the river.” -Lindsay Applegate In 1846 Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and 13 others from near Dallas, Oregon, headed south following old trapper trails into a remote region of Oregon Country. An Umpqua Indian showed them a foot trail that crossed the Calapooya Mountains, then on to Umpqua Valley, Canyon Creek, and the Rogue Valley. They next turned east and went over the Cascade Mountains to the Klamath Basin. The party devised pathways through canyons and mountain passes, connecting the trail south from the Willamette Valley with the existing California Trail to Fort Hall, Idaho. In August 1846, the first emigrants to trek the new southern road left Fort Hall. -

Southern Route

Chapter Eight Southern Route Capt. Levi Scott was the epitome of a self-made man of the American frontier – a bona fide “frontiersman.” Born February 8. 1797, and raised without benefit of loving parents on the edge of the frontier, the fiercely independent Scott had migrated west over the Oregon Trail in 1844, upon the untimely loss of his wife of twenty-five years. Scott was seizing what was to be his last chance to start life anew, on the new American frontier which was moving to distant Oregon. Owing to the excessive rains in 1844, the entire migration got underway late on the Oregon Trail. But halfway through the journey Capt. Scott demonstrated the leadership qualities he had developed while commanding a company in the Black Hawk Wars in Illinois against the Sac Indians from 1831 to 1833. According to his account, Scott was elected to assume the leadership of half of Nathaniel Ford’s trail followers, when they grew dissatisfied with their former leader. By the time Scott’s party reached Ft. Hall in early September, they traded their team and wagon with the proprietor of the fort for horses and pack-rigging, and proceeded on horseback for the remainder of the journey. Scott explained that their work oxen had become exhausted, and it was getting so late in the season that his party feared they might be caught by the winter snows in the mountains. Upon reaching the Dalles of the Columbia River late in October, the travelers had arrived at the point where most all emigrants sought out means to transport their families and equipment down this treacherous stretch in the journey. -

Bistorical Society Quarterly DIRECTOR JOHN TOWNLEY

NEVADA Bistorical Society Quarterly DIRECTOR JOHN TOWNLEY BOARD OF TRUSTEES The Nevada Historical Society was founded in 1904 for the purpose of investigating topics JOHN WRIGHT pertaining to the early history of Nevada and Chairman of collecting relics for a museum at its Reno facility where historical materials of many EDNA PATTERSON kinds are on display to the public and are av- Vice Chairman ailable to students and scholars. ELBERT EDWARDS Membership dues are: annual, S7.50; student, S3; sustaining, $25; life, $100; and patron, RUSSELL ELLIOTT $250. Membership applications and dues should be sent to the director. RUS-SELL McDONALD MARY ELLEN SADOVICH The Nevada Historical Society Quarterly pub- lishes articles, interpretive essays , and docu- WILBU R SHIPPERSON ments which deal with the history of Nevada . and of the Great Basin area. Particularly wef- come are manuscripts which examne the polit- ical, economic, cultural, and constitutional aspects of the history of this region. Material submitted for publication should be sent to the N. H .5. Quarterly, 4582 Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, Nevada 89109. Footnotes should be placed at the end of the manuscript, \vhich should be typed double spaced. The evalua- tion process will take approximately six to ten weeks. lassaere - Lakes "',,' , /\...y' ////f/, : //T;V; :.r// " . /, , . , f''''" . " ''///: ':/ /' / ,: / / , /" ,/,/ //'/ . ' -' . " . /r,///, '//. /// /", This portrayal of the 1850 Massacre was drawn by Paul Nyland as one of a series of historically oriented newspaper advertisements for Harold's Club of Reno, Massacre! What Massacre? An Inquiry into the Massacre of 1850 by Thomas N. Layton MASSACRE LAKE (Washoe County, Nevada) Some small lakes, or dry sinks, also called Massacre Lakes, east of Vya in the northern portion of the county... -

2019-20 General Catalog Was Produced by the Registrar's Office: Wendy Ivie, University Registrar, and Allison Baker, Administrative Program Specialist

Oregon Tech • University Catalog 2019-2020 1 Oregon Institute of Technology University Catalog © 2019-2020 www.oit.edu (541) 885-1000 3201 Campus Drive, Klamath Falls, OR 97601-8801 Hands-on education for real-world achievement. Oregon Tech • University Catalog 2019-2020 2 Welcome to Oregon Tech General Information The Oregon Tech Admissions Office is located on the first floor of the College Union on the Klamath Falls campus. It is open weekdays from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. to serve prospective students, applicants and their families, as well as high school guidance counselors, college-transfer advisors and teachers. If you are interested in seeing the Klamath Falls campus, the Admissions Office's visit coordinator can arrange for you to meet with a faculty member and an admissions counselor, tour the residence halls and the rest of the campus, sit in on a class and/ or talk with one of our coaches. To set up a campus visit, call (800) 422-2017 or (541) 885-1150. Hearing-impaired persons may call the TTY number: (541) 885-1072. You also can request a campus visit at www.oit.edu or by emailing [email protected]. If you wish to visit one of Oregon Tech's other campuses, the Admissions Office can provide you with a contact person who can make arrangements for you. Non-Discrimination Policy Non-Discrimination Policy Oregon Institute of Technology does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, ethnicity, national origin, gender, disability, age, religion, marital status, sexual orientation or gender identity in its programs and activities. -

Oregon Pioneer Wa-Wa: a Compilation of Addresses of Charles B. Moores Relating to Oregon Pioneer History

OREGON PIONEER WA-WA A COMPILATION OF ADDRESSES OF CHARLES B. MOORES RELATING TO OREGON PIONEER HISTORY PREFACE The within compilation of addresses represents an accumulation of years. Being reluctant to destroy them we are moved for our own personalsatisfaction, to preserve theni in printed form.They contain much that is commonplace, and much that is purely personal and local in character.There is a great surplus of rhetoric. There is possibly an excess of eulogy. There is considerable repetition.There are probably inaccuracies. Thereisnothing, however, included in the compilation that does not have some bearing on Oregon Pioneer History, and this, at least, gives it sonic value.As but a limited nuniber of copies are to be printed, and these arc solely for gratuitous distribution among a few friends, and others, having some interest in the subjects treated, we send the volume adrift, just as it is, without apology and without elimination. Portland, Oregon, March 10, 1923. CHAS. B. MOOnJiS. ADDRESSES Page Chenieketa Lodge No. 1, I. 0. 0. F I Completion of Building of the First M. E. Church of Salem, Oregon 12 Printers' Picnic, Salem, Oregon, 1881 19 Dedication of the Odd Fellows' Temple in Salem, Ore.,190L26 Fiftieth Anniversary Celebration Chemeketa Lodge,I. 0. 0. F. No. 1, Salem, Oregon 34 I)onatjon Land LawFiftieth Anniversary Portland Daily Oregonian 44 Annual Reunion Pioneer Association, Yambill County, Oregon50 Unveiling Marble Tablet, Rev. Alvin F. Wailer 62 Thirty-second Annual Reunion, Oregon State Pioneer Asso- ciation, 1904 69 Laying Cornerstone Eaton Hall, Willarnette University,De- cember 16, 1908 87 Champoeg, May 1911 94 Dedication Jason Lee Memorial Church, Salem, June, 1912 100 Memorial Address, Champocg, Oregon, May 2nd, 1914 107 Oregon M. -

MEN of CHAMPOEG Fly.Vtr,I:Ii.' F

MEN OF CHAMPOEG fly.vtr,I:ii.' f. I)oI,I,s 7_ / The Oregon Society of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution is proud to reissue this volume in honor of all revolutionaryancestors, this bicentennialyear. We rededicate ourselves to theideals of our country and ofour society, historical, educational andpatriotic. Mrs. Herbert W. White, Jr. State Regent Mrs. Albert H. Powers State Bicentennial Chairman (r)tn of (]jjainpog A RECORD OF THE LIVES OF THE PIONEERS WHO FOUNDED THE OREGON GOVERNMENT By CAROLINE C. DOBBS With Illustrations /4iCLk L:#) ° COLD. / BEAVER-MONEY. COINED AT OREGON CITY, 1849 1932 METROPOLITAN PRESS. PUBLISHERS PORTLAND, OREGON REPRINTED, 1975 EMERALD VALLEY CRAFTSMEN COTTAGE GROVE, OREGON ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS MANY VOLUMES have been written on the history of the Oregon Country. The founding of the provisional government in 1843 has been regarded as the most sig- nificant event in the development of the Pacific North- west, but the individuals who conceived and carried out that great project have too long been ignored, with the result that the memory of their deeds is fast fading away. The author, as historian of Multnomah Chapter in Portland of the Daughters of the American Revolution under the regency of Mrs. John Y. Richardson began writing the lives of these founders of the provisional government, devoting three years to research, studying original sources and histories and holding many inter- views with pioneers and descendants, that a knowledge of the lives of these patriotic and far-sighted men might be preserved for all time. The work was completed under the regency of Mrs.