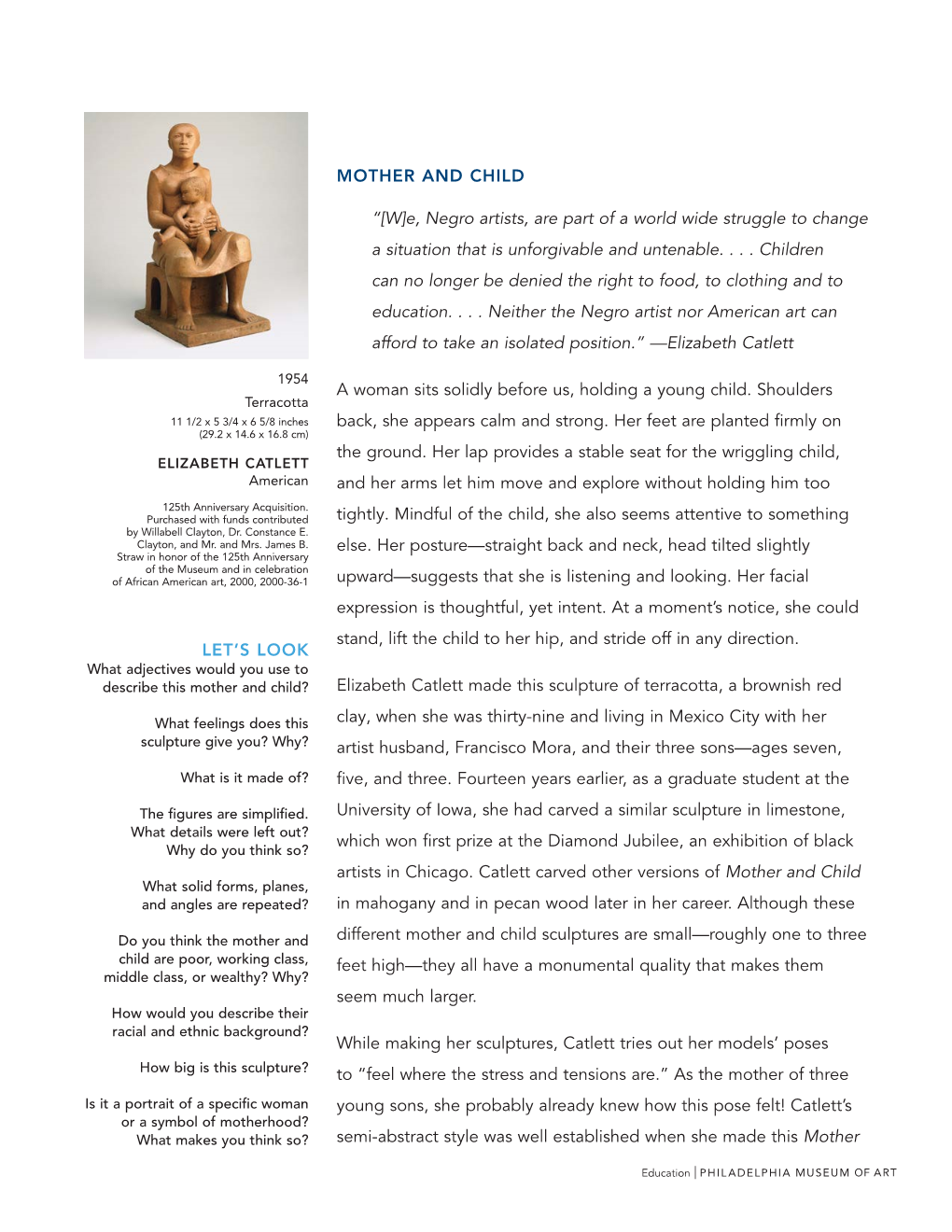

LET's LOOK MOTHER and CHILD “[W]E, Negro Artists, Are Part of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Huella Majistral for Divi

Majestic Impression La Huella Magistral September 22 through October 28, 2017 Curated by Nitza Tufiño Jaime Montiel Rini -Templeton This exhibition features the works of artists printmakers who are members of the ''Consejo Grafico '' (The Graphic Council), a national Latinx organization of ''Talleres'' printmaking workshops. The portfolio of prints is by selected artists, who have created original works honoring a master printmaker who has influenced him or her. The featured artists are Rene Arceo; Pepe Coronado; Francisco X Siqueiros; Marianne Sadowski; Kay Brown; Poli Marichal; Juan R Fuentes; Richard Xavier Serment; Ramiro Rodriguez; Joe Segura; Paul del Bosque; Sandra C Fernandez; Maceo Montoya; Lezlie Salkowitz Montoya; Malaquias Montoya; Loanda Lozano; Nitza Tufiño; Betty Cole; Eliezer Berrios; and Marcos Dimas. In addition, during this event, there will be an adjoining exhibit featuring the work from members of the Dominican York Proyecto GRAFICA (DYPG) and Taller Boricua’s Rafael Tufiño Printmaking Workshop. Since 2000, a group of independent printmaking workshops began to form a coalition, the CONSEJO GRÁFICO, to "advance Latino printmakers' capacity and legacy in the United States." This beautiful series of prints constitutes their third Portfolio Exchange. The Portfolio, an edition of 30, gathers 19 participating artists, each contributing to print MAJESTIC IMPRESIONS 2017 1 The Portfolio's title, LA HUELLA MAGISTRAL: HOMAGE TO MASTER PRINTMAKERS, reveals the charitable purpose of the participating artists: to honor their teachers — master printmakers who taught, mentored, or inspired them. These artists share moral values and social ideals with those who inspired them: the defense of poor and oppressed peoples, solidarity with workers, a commitment to public education. -

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

SCHEMA 2019 to 2020.Pdf

schema / 2019–2020 the year in review THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2019–2020 schema 2019–2020 THE YEAR IN REVIEW 4 SCMA100 \ the making of a museum From the Director Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion at SCMA Faculty Perspective: Matt Donovan 18 connecting people to art ON VIEW July 2019–June 2020 The smith college Younès Rahmoun: Scholarly Convening and Performance Defiant Vision: Prints & Poetry by Munio Makuuchi museum of art A Dust Bowl of Dog Soup: Picturing the Great Depression Buddhas | Buddhisms: Across and Beyond Asia cultivates inquiry Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem Museum Studies Course and reflection Program Highlights by connecting people to art, The Ancient World Gallery: A Reinstallation 36 connecting people to ideas ideas and each other A Place for Connection Academic Engagement: Teaching and Learning with the Collection Museums Concentration Museums Today Student Engagement: Remote Internship Program Student Perspective: Molly McGehee ‘21 Tryon Prizes for Writing and Art 2020 Student Perspective: Hannah Gates ‘22 Dancing the Museum Amanda Williams: 17th Annual Miller Lecturer in Art and Art History 50 connecting people to each other Member Engagement Membership Program Highlights Student Perspective: Emma Guyette ‘20 SCMA100 Gala Supporters Advisory Groups Gifts to the Museum Honoring Joan Lebold Cohen ‘54 66 art acquisition highlights 72 gifts and purchases of art 84 parting words and more Parting Words SCMA by the Numbers Museum Staff/Student Assistants the making of a museum from the director THE MAKING OF A MUSEUM is as layered as the works inside its walls. It raises questions about who we are and who we want to be; what we do and why we do it; who our audiences are and how best to serve them. -

La Célula Gráfica. Artistas Revolucionarios En México, 1919-1968, Muestra Que Aborda El Compromiso De Los Artistas Mexicanos Del Siglo XX

Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Ciudad de México, a 22 de noviembre de 2019 Boletín núm. 1800 La célula gráfica. Artistas revolucionarios en México, 1919-1968, muestra que aborda el compromiso de los artistas mexicanos del siglo XX • Las 180 piezas permanecerán en exposición del 22 de noviembre de 2019 al 23 de febrero de 2020 en el Museo Nacional de la Estampa El Museo Nacional de la Estampa (Munae) del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL) exhibirá a partir del 22 de noviembre la muestra La célula gráfica. Artistas revolucionarios en México, 1919-1968, cuyo objetivo es valorar la función del arte como compromiso social. Esta exposición, bajo la curaduría de Ana Carolina Abad, se centra en el trabajo de artistas que, a partir del fin de la Revolución Mexicana y hasta la década de 1960, asumieron la tarea de crear imágenes con mensajes generalmente de índole social. La célula gráfica es una gran oportunidad para conocer parte del acervo del Munae que pocas veces se ha exhibido, principalmente de grabadores reconocidos, como Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Luis Arenal, Xavier Guerrero, Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins, Raúl Anguiano, Ángel Bracho, Francisco Dosamantes, Alfredo Zalce, Arturo García Bustos, Francisco Mora y Francisco Moreno Capdevila. Igualmente contempla la obra de Andrea Gómez, Sarah Jiménez y Mariana Yampolsky. Paseo de la Reforma y Campo Marte s/n, Módulo A, 1.er Piso Col. Chapultepec Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo C.P. 11560, Ciudad de México, tel. (55) 1000 5600 Ext. 4086 [email protected] Para Emilio Payán, director del Munae, La célula gráfica. -

Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents

Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents Page Contents 3 Image List 5 Woman Holding a Child with an Apple in its Hand,, Angelica Kauffmann 6 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Bernadette Brown 7 Princess Eudocia Ivanovna Galitzine as Flora, Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun 8 Lesson Plan for Flora Written by Melissa Nickerson 10 Jeanette Wearing a Bonnet, Mary Cassatt 12 Lesson Plan for Jeanette Wearing a Bonnet Written by Zelda B. McAllister 14 Sturm (Riot), Käthe Kollwitz 15 Lesson Plan for Sturm Written by Susan Price 17 Illustration for "Le mois de la chevre," Marie Laurencin 18 Lesson Plan for Illustration for "Le mois de la chevre" Written by Bernadette Brown 19 Illustration for Juste Present, Sonia Delaunay 20 Lesson Plan for Illustration for Juste Present Written by Melissa Nickerson 22 Gunlock, Utah, Dorothea Lange 23 Lesson Plan for Gunlock, Utah Written by Louise Nickelson 28 Newsstand, Berenice Abbott 29 Lesson Plan for Newsstand Written by Louise Nickelson 33 Gold Stone, Lee Krasner 34 Lesson Plan for Gold Stone Written by Melissa Nickerson 36 I’m Harriet Tubman, I Helped Hundreds to Freedom, Elizabeth Catlett 38 Lesson Plan for I’m Harriet Tubman Written by Louise Nickelson Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership 1 Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents (continued) Page Contents 46 Untitled, Helen Frankenthaler 48 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Virginia Catherall 51 Fourth of July Still Life, Audrey Flack 53 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 55 Bibliography 2 Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Image List 1. -

LET's LOOK ZAPATA Diego Rivera Created This Print of Revolutionary

ZAPATA Diego Rivera created this print of revolutionary leader and land- reform champion Emiliano Zapata in 1932, twelve years after the end of the Mexican Revolution. Dressed in simple white peasant clothing, Zapata and his horse stand over the lifeless figure of a soldier. The farm workers for whose cause he fought gather behind him. In con- 1932 Lithograph trast to the soldier’s sword, Zapata and his followers carry farming Image: 16 1/4 × 13 1/8 inches (41.3 × 33.4 cm) tools as weapons, showing their close ties to the land. Sheet: 17 1/16 × 14 inches (43.4 × 35.5 cm) ABOUT THIS ARTIST JOSÉ DIEGO MARÍA RIVERA Mexican Diego Rivera (1886–1957) was born in Mexico to parents of Purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund from the Carl and Laura Zigrosser Collection, 1976, 1976-97-114 European and Mexican ancestry. Because of his amazing drawing ability, he was accepted to the Academia de San Carlos, a pres- tigious art school in Mexico City, at the age of twelve. When Rivera LET’S LOOK What do you think is was twenty-one, he received a government scholarship to travel in happening in this picture? Spain and France. There he met leading modern artists, including What happened before Pablo Picasso, and learned to paint in the Cubist style that was this moment? popular in Europe. What will happen next? In 1921 Rivera returned home. He and other Mexican artists began How is the main figure, Zapata, dressed? to look to pre-Columbian artifacts (made before the arrival of What is he holding? Columbus to the Americas) and native folk art for inspiration, hoping How are the people to create works that were uniquely Mexican. -

Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Opularp

Schmucker Art Catalogs Schmucker Art Gallery Fall 2020 Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica opularP Carolyn Hauk Gettysburg College Joy Zanghi Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs Part of the Book and Paper Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, and the Printmaking Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Hauk, Carolyn and Zanghi, Joy, "Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica opularP " (2020). Schmucker Art Catalogs. 35. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/artcatalogs/35 This open access art catalog is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mexico and the People: Revolutionary Printmaking and the Taller De Gráfica Popular Description During its most turbulent and formative years of the twentieth century, Mexico witnessed decades of political frustration, a major revolution, and two World Wars. By the late 1900s, it emerged as a modernized nation, thrust into an ever-growing global sphere. The revolutionary voices of Mexico’s people that echoed through time took root in the arts and emerged as a collective force to bring about a new self- awareness and change for their nation. Mexico’s most distinguished artists set out to challenge an overpowered government, propagate social-political advancement, and reimagine a stronger, unified national identity. Following in the footsteps of political printmaker José Guadalupe Posada and the work of the Stridentist Movement, artists Leopoldo Méndez and Pablo O’Higgins were among the founders who established two major art collectives in the 1930s: Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR) and El Taller de Gráfica opularP (TGP). -

July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 FY16: a LOOK BACK

Georgia Museum of Art Annual Report July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016 FY16: A LOOK BACK This fiscal year, running from July 1, 2015, a dramatic uptick in attendance during the to June 30, 2016, was, as usual, packed with course of the show. Heather Foster, an MFA activities at the Georgia Museum of Art. The student at UGA in painting and an intern in exhibition El Taller de Gráfica Popular: Vida y our education department, created a series of Arte kicked off our fiscal year, providing the Pokemon-inspired cards highlighting different inspiration for our summer Art Adventures objects in the exhibition. We also embarked programming in 2015 as well as lectures, upon our first Georgia Funder, using UGA’s films, family programs and much more. We crowd-funding platform to raise money for the engaged in large amounts of Spanish-language exhibition’s programming. Caroline Maddox, programming, and the community responded our director of development, left for a position positively. at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Laura Valeri, associate curator, for Georgetown In July, the Friends of the Georgia Museum University Press. of Art kicked off a three-month campaign to boost membership by 100 households. Through In November, we focused attention on three carefully crafted marketing emails and the first major gifts from the George and Helen Segal in a series of limited-edition mugs available only Foundation, devoting an entire exhibition to through membership, they did just that and them. Other major acquisitions included a more. painting by Frederick Carl Frieseke (due to the generosity of the Chu Family Foundation), one In August, with the beginning of the university’s by Anthony Van Dyck and studio (from Mr. -

La Revolución Mexicana

Media Contact Rachel Trevino, Head of Communications and Marketing (o) 210.805.1754 (c) 210.854.8889 [email protected] La Revolución Mexicana: 100 Years Later Marks Centennial of the Mexican Revolution with Works of Art From One of the Greatest Living Mexican Printmakers Exhibition on View at McNay Art Museum through November 24 San Antonio, TX (August 29, 2019) – Opening today at McNay Art Museum, La Revolución Mexicana: 100 Years Later marks the centennial of the end of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) with a spotlight on Michoacan printmaker Artemio Rodriguez. His portfolio of 18 linoleum block prints created in 2010 to mark the 100-year anniversary of the beginning of the Mexican Revolution is on view together for the first time at the McNay. The brilliantly contrasting black and white linocuts include portraits of prominent figures on both sides of the struggle. The artist’s portrait of dictator Porfirio Díaz and the Eurocentric nature of his rule strikingly contrasts the portrait of the great revolutionary leader, Emiliano Zapata, on horseback in rural Mexico with small farms and mountains in the background. “Many Mexican families fleeing the violence of the Revolution came to San Antonio and surrounding areas in search of safety,” said Lyle Williams, McNay Curator of Prints and Drawings. “San Antonio’s ties to the Mexican Revolution run very deep, and the exhibition is timed to be on view during the city’s Diez y Seis celebrations in September.” Complementing Rodriguez’s portfolio are prints from the McNay’s extensive collection of portraits of Zapata by Diego Rivera, Melanie Cervantes, Ignacio Aguirre, Sarah Jiménez, Francisco Mora, José Clemente Orozco, Luis "Teak" Rodriguez, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. -

Catalogo De Las Exposiciones De Arte En 1953

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1954.sup1.2475 JUSTINO FERNANDEZ CATALOGO DE LAS EXPOSICIONES DE ARTE EN 1953 SUPLEMENTO DEL NUM. 22 DE LOS ANALES DEL INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES ESTETICAS MEXICO 1 9 5 4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1954.sup1.2475 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1954.sup1.2475 Merece a todas luces el lugar de honor de las exposiciones capitalinas del afio de 1953 la Exposicion de Ayte Mesicano, instal ada en el Palacio de Bellas Artes por el Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y en 'la que colaboraron tanto el Insltituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, como el Instituto Nacional Indigenista. La instalaci6n, que ocupa practicamente todas las salas de exhibicion del edificio, es decir, 10 que constituye el Museo Nacional de Artes Plasticas, es excelente no obs tante su dificil realizacion, por 10 que merecen una felicitacion todos los encar gados de Ilevarla a cabo. En realidad no desmerece esta exposicion respecto a las que fueron presentadas en 1952 en Paris, Estocolmo y Londres; cierto que algunas piezas se suprimieron, mas, en carnbio se ha enriquecido con otras y, adernas, se ha contado con las obras murales de Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros y Tamayo que com pletan la seccion del arte contemporaneo, Alguna seccion resulta un poco exigua, me refiero a la de la pintura del siglo XIX, mas, en verdad, no era posible segura mente disponer de mayor espacio, Es de lamentar que no se haya publicado un ca talogo detallado de la exposicion cornpleta, pues la guia con que se cuenta no es suficiente para la visita ni para conmernorar tan magno suceso artistico. -

Josfi GUADALUPE POSADA, the CORRIDO, and the MEXICAN

37^ //$ I HOJAS VOLANTES: JOSfi GUADALUPE POSADA, THE CORRIDO, AND THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Melody Mock, B.F.A. Denton, Texas August, 1996 37^ //$ I HOJAS VOLANTES: JOSfi GUADALUPE POSADA, THE CORRIDO, AND THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Melody Mock, B.F.A. Denton, Texas August, 1996 Mock, Melody. Hojas Volantes: Jose Guadalupe Posada, the Corrido, and the Mexican Revolution. Master of Arts (Art History), August 1996, 101 pp., 26 illustrations, references, 138 titles. This thesis examines the imagery of Jose Guadalupe Posada in the context of the Mexican Revolution with particular reference to the corrido as a major manifestation of Mexican culture. Particular emphasis is given to three corridos: "La Cucaracha," "La Valentina," and "La Adelita." An investigation of Posada's background, style, and technique places him in the tradition of Mexican art. Using examples of works by Posada which illustrate Mexico's history, culture, and politics, this thesis puts Posada into the climate of the Porfiriato and Revolutionary Mexico. After a brief introduction to the corrido, a stylistic analysis of each image, research into the background of the song and subject matter, and comments on the music draw together the concepts of image, music, and text. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Posada's Background Statement of the Problem Methodology 2. -

Culture Shapes Community - January 5, 2006 the Mexican Fine Arts Ce

Culture Shapes Community - January 5, 2006 The Mexican Fine Arts Ce... http://www.cultureshapescommunity.org/index.php?option=com_conten... home about news resources forums tell your story home news press january 5, 2006 the mexican fine arts center museum presents "the african presence in mexico" Username January 5, 2006 The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum Password presents "The African Presence in Mexico" Remember me The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum organizes its most important exhibition to Login date: Password Help The African Presence in México: From Yanga to the Present February 11 – September 3, 2006 Hear the Voices Opportunities for community Chicago – The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum (MFACM) is showcasing The art at Mass MOCA by Rebecca Uchill African Presence in México, the most comprehensive project ever organized about African contributions to Mexican culture featuring three exhibitions: The African Nuestras Raíces TOP project Presence in Mexico: From Yanga to the Present, Roots, Resistance and Recognition, by Eric Toensmeier and Common Goals, Common Struggles, and Common Ground. The project also Rallying People Together by features numerous public and educational programs throughout the seven months Carol Bebelle that the exhibitions will be presented. The project examines the missing chapter in Mexican history that highlights the African contributions to Mexican culture over the past nearly 500 years. These groundbreaking exhibitions also attempt to stimulate Upcoming Events a better understanding of Mexican culture among Mexicans and non-Mexicans alike. No Latest Events The exhibitions will run from February 11 – September 3, 2006 and subsequently tour to at least four other museums in the U.S.