The Second Recovery of Bison Credit: U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Faster Registration Form

/ & NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior - - National Park Service - •- -' f\VM;OMAl NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES FASTER REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Hornaday Camp other name/site number: 246F362 2. Location street & number: Montana Highway 200 not for publication: n/a vicinity: n/a city/town: Sand Springs state: Montana code: MT county: Gar field code: 033 zip code: 59077 3. Classification Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: site Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing ____ ____ building(s) 1 ____ sites ____ ____ structures ____ ____ objects Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: n/a 4. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. ____ See continuation sheet. Signature of certifying official U 0 Date 0 State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. __ See continuation sheet. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 5. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: v/ entered in the National Register (LuJfflWfftyjL,(I ' MU.hD __ See continuation sheet. -

5Th American Bison Society Meeting and Workshop

5th American Bison Society Meeting and Workshop Banff, Alberta September 26-29, 2016 Cover photos: Bison photos: © Kent Redford; Treaty signing: © Stephen Legault h Message from the Governor General I am delighted to extend my warmest regards to all those gathered for the 2016 American Bison Society Meeting. Over a century ago, long before the advent of ‘green’ living, a passionate group of individuals banded together to revitalize the dwindling North American bison population. These magnificent animals had been ravaged by human greed, almost to the point of extinction. Yet, through the efforts of the American Bison Society, the bison have returned to the wild in great numbers. The Society continues to play an important role in ensuring the survival of the bison. Its members have adopted the values of preservation and conservation, and are sharing this knowledge with the next generation, so that they may carry on this essential task. I commend the Society on its achievements and I wish everyone a most enjoyable celebration. David Johnston September 2016 5th American Bison Society Meeting and Workshop H American Bison Society h Welcome from WCS Dear colleagues, Welcome to the fifth bi-annual American Bison Society meeting and workshop. For the first time, we are hosting this meeting of bison enthusiasts, managers, producers, advocates, philanthropists, and artists in Canada. Not only is Banff a beautiful setting, it also plays a crucial role in the history of bison in North America. Over the next three days we will come together to share stories, learn about our work across North America and, finally, celebrate the second anniversary of the Buffalo Treaty. -

Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BUFFALO HUNT: INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND THE VIRTUAL EXTINCTION OF THE NORTH AMERICAN BISON M. Scott Taylor Working Paper 12969 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12969 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2007 I am grateful to seminar participants at the University of British Columbia, the University of Calgary, the Environmental Economics workshop at the NBER Summer Institute 2006, the fall 2006 meetings of the NBER ITI group, and participants at the SURED II conference in Ascona Switzerland. Thanks also to Chris Auld, Ed Barbier, John Boyce, Ann Carlos, Charlie Kolstad, Herb Emery, Mukesh Eswaran, Francisco Gonzalez, Keith Head, Frank Lewis, Mike McKee, and Sjak Smulders for comments; to Michael Ferrantino for access to the International Trade Commission's library; and to Margarita Gres, Amanda McKee, Jeffrey Swartz, Judy Hasse of Buffalo Horn Ranch and Andy Strangeman of Investra Ltd. for research assistance. Funding for this research was provided by the SSHRC. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by M. Scott Taylor. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison M. Scott Taylor NBER Working Paper No. 12969 March 2007 JEL No. F1,Q2,Q5,Q56 ABSTRACT In the 16th century, North America contained 25-30 million buffalo; by the late 19th century less than 100 remained. -

Sky Island Grassland Assessment: Identifying and Evaluating Priority Grassland Landscapes for Conservation and Restoration in the Borderlands

Sky Island Grassland Assessment: Identifying and Evaluating Priority Grassland Landscapes for Conservation and Restoration in the Borderlands David Gori, Gitanjali S. Bodner, Karla Sartor, Peter Warren and Steven Bassett September 2012 Animas Valley, New Mexico Photo: TNC Preferred Citation: Gori, D., G. S. Bodner, K. Sartor, P. Warren, and S. Bassett. 2012. Sky Island Grassland Assessment: Identifying and Evaluating Priority Grassland Landscapes for Conservation and Restoration in the Borderlands. Report prepared by The Nature Conservancy in New Mexico and Arizona. 85 p. i Executive Summary Sky Island grasslands of central and southern Arizona, southern New Mexico and northern Mexico form the “grassland seas” that surround small forested mountain ranges in the borderlands. Their unique biogeographical setting and the ecological gradients associated with “Sky Island mountains” add tremendous floral and faunal diversity to these grasslands and the region as a whole. Sky Island grasslands have undergone dramatic vegetation changes over the last 130 years including encroachment by shrubs, loss of perennial grass cover and spread of non-native species. Changes in grassland composition and structure have not occurred uniformly across the region and they are dynamic and ongoing. In 2009, The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) launched its Sky Island Grassland Initiative, a 10-year plan to protect and restore grasslands and embedded wetland and riparian habitats in the Sky Island region. The objective of this assessment is to identify a network of priority grassland landscapes where investment by the Foundation and others will yield the greatest returns in terms of restoring grassland health and recovering target wildlife species across the region. -

Bison and Biodiversity: History of a Keystone Species

Spring/Summer 2020 MONTANA NTO PROMOTE ANDa CULTIVATE THEt APPRECIATION,u UNDERSTANDINGr AND STEWARDSHIPa OFli NATURE THROUGHs EDUCATIONt Bison and Biodiversity: History of a Keystone Species Heartbeats & Hibernation | All About Antlions | Birding in Spain and Montana | Visions of Earth MONTANA Naturalist Spring/Summer 2020 inside Features 4 BISON AND BIODIVERSITY: A CASE STUDY Exploring the history of North America’s keystone herbivore BY GIL GALE 8 HEARTBEATS AND HIBERNATION 4 8 IN THE ROCKIES Getting at the heart of surviving winter in Montana Departments BY HEATHER MCKEE 3 TIDINGS 10 NATURALIST NOTES Antlions: A Conversation of Observations 22 12 GET OUTSIDE GUIDE Book review: The Lost Words; 10 nature writing activity; phenology scavenger hunt; Kids’ Corner: tree painting by Lila Farrell; Pablo 4th-grade science projects 17 IMPRINTS Farewell to Lisa Bickell; upcoming exhibits; new summer 24 camp offerings; welcome to 24 Jennifer Robinson; Drop in with a FAR AFIELD Naturalist; As To The Mission; Birding in Spain 2019 auction thank yous BY PEGGY CORDELL 17 19 26 VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT MAGPIE MARKET Cover – A Bullock’s Oriole (Icterus bullockii) Alyssa Giffin perches on a branch above Pauline Creek at the National Bison Range on a gorgeous June 27 22 REFLECTIONS day. Bullock’s Orioles are summer residents COMMUNITY FOCUS Visions of Earth in Montana. Photo by Merle Ann Loman, Working for Wilderness: amontanaview.com. The Great Burn Conservation No material appearing in Montana Naturalist Alliance may be reproduced in part or in whole without the BY ALLISON DE JONG written consent of the publisher. All contents © 2020 The Montana Natural History Center. -

Initial Layout

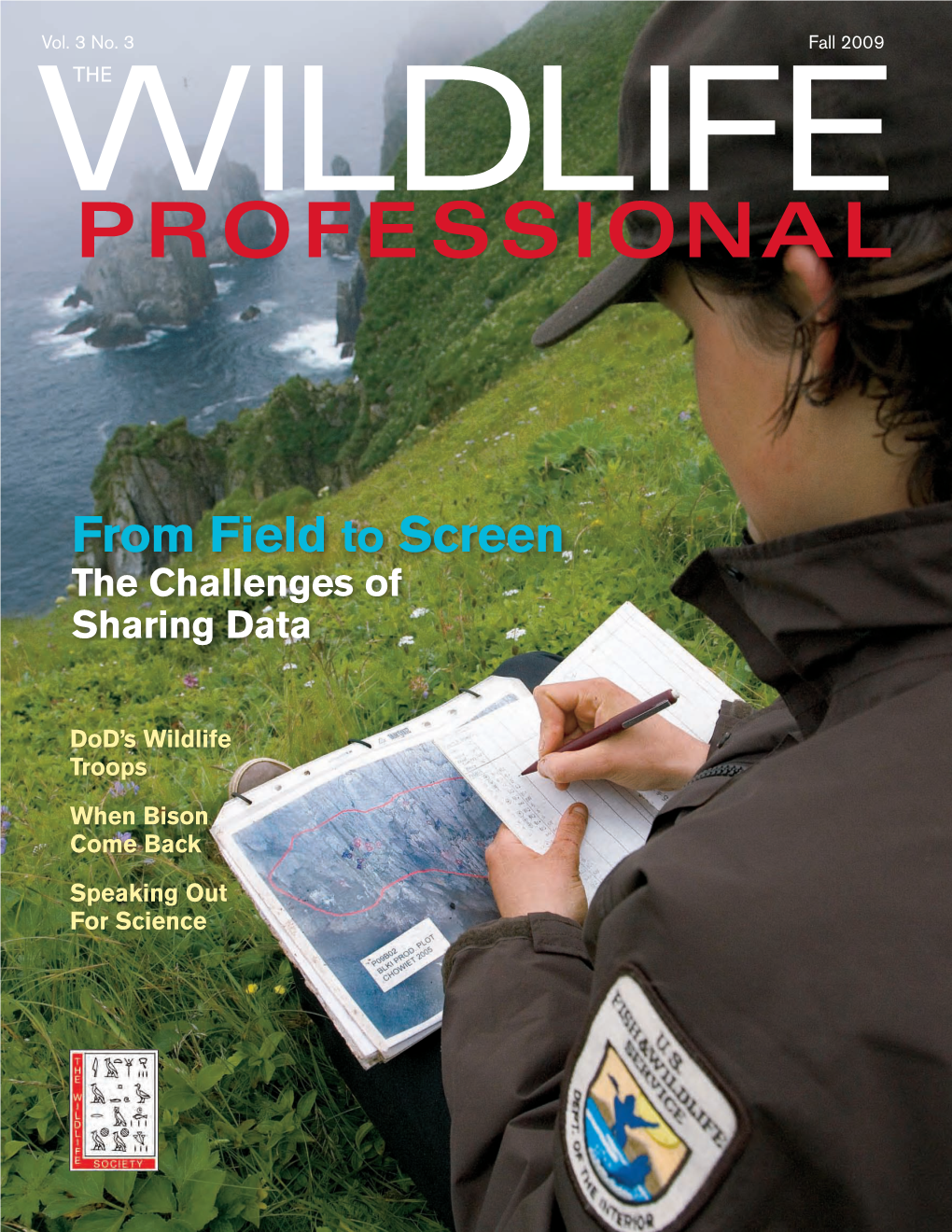

ison are wild animals. Although pearance of once numerous herds. A By 1888, when C. J. they are now raised commer- demand from the eastern United States Bcially—the Kansas Buffalo Asso- for bison products, both meat and hides, “Buffalo” Jones went ciation currently has 107 members raising coupled with the arrival in western Kan- 8,600 animals—bison do not have the sas of railroad lines that provided the searching in this region for same temperament as their domesticated means for cheaply and efficiently trans- cattle relatives. Bison, or buffalo, appear porting those products, led to a massive bison to capture alive, he docile when grazing and ruminating, but killing of bison. The killing was unregu- the mind behind the massive forehead and lated and thorough and was condoned by found a total of 37 animals. curved horns still thinks the way its an- the U.S. and state governments, anxious cestors thought. It is an animal that pre- to subdue free-roaming Indian tribes who and Bison athabascae), skeletal remains fers to run, but it is ready to fight when depended upon buffalo for food, materi- of extinct forms (such as Bison latifrons, threatened. als for shelter, and numerous other neces- Bison alleni, and Bison antiquus) can be Humans and bison have interacted sities, as well as for spiritual needs. recognized primarily by their continued for thousands of years in North America, Small remnant herds of bison remained diminution in overall size and smaller but that interaction until recent times has after the departure of the hide-hunters, horn cores, which also change in shape. -

Special Activities

59th Annual International Conference of the Wildlife Disease Association Abstracts & Program May 30 - June 4, 2010 Puerto Iguazú Misiones, Argentina Iguazú, Argentina. 59th Annual International Conference of the Wildlife Disease Association WDA 2010 OFFICERS AND COUNCIL MEMBERS OFFICERS President…………………………….…………………...………..………..Lynn Creekmore Vice-President………………………………...…………………..….Dolores Gavier-Widén Treasurer………………………………………..……..……….….……..…….Laurie Baeten Secretary……………………………………………..………..……………….…Pauline Nol Past President…………………………………………………..………Charles van Riper III COUNCIL MEMBERS AT LARGE Thierry Work Samantha Gibbs Wayne Boardman Christine Kreuder Johnson Kristin Mansfield Colin Gillin STUDENT COUNCIL MEMBER Terra Kelly SECTION CHAIRS Australasian Section…………………………..……………………….......Jenny McLelland European Section……………………..………………………………..……….….Paul Duff Nordic Section………………………..………………………………..………….Erik Ågren Wildlife Veterinarian Section……..…………………………………..…………Colin Gillin JOURNAL EDITOR Jim Mills NEWSLETTER EDITOR Jenny Powers WEBSITE EDITOR Bridget Schuler BUSINESS MANAGER Kay Rose EXECUTIVE MANAGER Ed Addison ii Iguazú, Argentina. 59th Annual International Conference of the Wildlife Disease Association ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Executive President and Press, media and On-site Volunteers Conference Chair publicity Judy Uhart Marcela Uhart Miguel Saggese Marcela Orozco Carlos Sanchez Maria Palamar General Secretary and Flavia Miranda Program Chair Registrations Elizabeth Chang Reissig Pablo Beldomenico Management Patricia Mendoza Hebe Ferreyra -

The Destruction of the Bison an Environmental History, –

front.qxd 1/28/00 10:59 AM Page v The Destruction of the Bison An Environmental History, 1750–1920 ANDREW C. ISENBERG Princeton University front.qxd 1/28/00 10:59 AM Page vi published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Andrew C. Isenberg 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Ehrhardt 10/12 pt. System QuarkXPress [tw] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Isenberg, Andrew C. (Andrew Christian) The destruction of the bison : an environmental history, 1750–1920 / Andrew C. Isenberg. p. cm. – (Studies in environment and history) Includes index. isbn 0-521-77172-2 1. American bison. 2. American bison hunting – History. 3. Nature – Effect of human beings on – North America. I. Title. ql737.u53i834 2000 333.95´9643´0978 – dc21 99-37543 cip isbn 0 521 77172 2 hardback front.qxd 1/28/00 10:59 AM Page ix Contents Acknowledgments page xi Introduction 1 1 The Grassland Environment 13 2 The Genesis of the Nomads 31 3 The Nomadic Experiment 63 4 The Ascendancy of the Market 93 5 The Wild and the Tamed 123 6 The Returns of the Bison 164 Conclusion 193 Index 199 ix intro.qxd 1/28/00 11:00 AM Page 1 Introduction Before Europeans brought the horse to the New World, Native Americans in the Great Plains hunted bison from foot. -

Second Chance for the Plains Bison

ARTICLE IN PRESS BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION xxx (2007) xxx– xxx available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Review Second chance for the plains bison Curtis H. Freesea,*, Keith E. Auneb, Delaney P. Boydc, James N. Derrd, Steve C. Forresta, C. Cormack Gatese, Peter J.P. Goganf, Shaun M. Grasselg, Natalie D. Halbertd, Kyran Kunkelh, Kent H. Redfordi aNorthern Great Plains Program, World Wildlife Fund, P.O. Box 7276, Bozeman, MT 59771, USA bMontana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, 1420 E 6th Avenue, Helena, MT 59620, USA cP.O. Box 1101, Redcliff, AB, Canada T0J 2P0 dDepartment of Veterinary Pathobiology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-4467, USA eFaculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada T6G 2E1 fUSGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, P.O. Box 173492, Bozeman, MT 59717-3492, USA gLower Brule Sioux Tribe, Department of Wildlife, Fish and Recreation, P.O. Box 246, Lower Brule, SD 57548, USA hNorthern Great Plains Program, World Wildlife Fund, 1875 Gateway South, Gallatin Gateway, MT 59730, USA iWCS Institute, Wildlife Conservation Society, 2300 Southern Blvd., Bronx, NY 10460, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Before European settlement the plains bison (Bison bison bison) numbered in the tens of mil- Received 30 July 2006 lions across most of the temperate region of North America. Within the span of a few dec- Received in revised form ades during the mid- to late-1800s its numbers were reduced by hunting and other factors 12 November 2006 to a few hundred. The plight of the plains bison led to one of the first major movements in Accepted 27 November 2006 North America to save an endangered species. -

Species of Common Conservation Concern (SCCCWT)

XXIII Meeting of the Canada/Mexico/U.S. Trilateral Committee for Wildlife and Ecosystem Conservation and Management National Conservation Training Center, Shepherdstown, West Virginia April 8 – 13, 2018 Working Table Agenda: Species of Common Conservation Concern (SCCCWT) Co-Chairs: • Melida T. Tajbakhsh, Chief, Western Hemisphere Branch, International Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), United States • Jose Francisco Bernal Stoopen, Director de Especies Prioritarias para la Conservación, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP), México • Mary Jane Roberts, Species at Risk Management, Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), Canada Facilitator: • Maricela Constantino, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [email protected], 571.969-9804 (cell) Remote Access: Remote connection is available for presenters and participants. For audio access use the information below (Please note we are limited to 20 lines – please advise the Facilitator, Maricela Constantino, [email protected] if you plan to participate and for what items): Toll Free Conference Call: Mexico +001-866-295-6360 USA and Canada 866-692-3582 Participant Passcode: 34281388# Remote access to view or present a powerpoint is available through the internet using the Webex platform. Please contact [email protected] directly to obtain instructions for connection via Webex. Trilateral Committee Priorities 2014-2017 • Climate Change with a Focus on Adaptation SCCCWT • Landscape and Seascape Conservation Including Connectivity and Area Based Conservation Partnerships • Wildlife Trafficking • Monarch Butterfly Conservation Working Table Priorities for 2017-2018 • Landscape and Seascape Conservation Including Connectivity and Area Based Conservation Partnerships • Wildlife Trafficking Monday, April 9, 2018 Room: Instructional East –114. (8:45 – 9 am Eastern) AGENDA ITEM 1 : Welcome, Introductions, and Adoption of the Agenda; 2017-18 Action Items Report; and Country Updates COLLABORATORS & CONTACTS: Co-chairs and Facilitator – Melida T. -

William T. Hornaday Papers

William T. Hornaday Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Ruth Wennersten and Mary Wolfskill Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2013 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms013033 Collection Summary Title: William T. Hornaday Papers Span Dates: 1866-1975 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1906-1936) ID No.: MSS52126 Creator: Hornaday, William T. (William Temple), 1854-1937 Extent: 39,000 items ; 111 containers plus 4 oversize ; 44.8 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Conservationist, zoologist, and taxidermist. Correspondence, diaries and journals, production materials for articles and books, notebooks, financial papers, clippings, scrapbooks, memorabilia, and other papers reflecting Hornaday's career, particularly as director of New York Zoological Park, 1896-1926. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Akeley, Carl Ethan, 1864-1926--Correspondence. Andrews, Roy Chapman, 1884-1960--Correspondence. Baker, Newton Diehl, 1871-1937--Correspondence. Beard, Daniel Carter, 1850-1941--Correspondence. Beebe, William, 1877-1962--Correspondence. Bessey, Charles E. (Charles Edwin), 1845-1915--Correspondence. Buck, Frank, 1884-1950--Correspondence. Burroughs, John, 1837-1921--Correspondence. Carnegie, Andrew, 1835-1919--Correspondence. Coues, Elliott, 1842-1899--Correspondence. Ditmars, Raymond Lee, 1876-1942--Correspondence. -

First Insights Into the Fecal Bacterial Microbiota of the Black–Tailed Prairie Dog (Cynomys Ludovicianus) in Janos, Mexico I

Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 42.1 (2019) 127 First insights into the fecal bacterial microbiota of the black–tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) in Janos, Mexico I. Pacheco–Torres, C. García–De la Peña, D. R. Aguillón–Gutiérrez, C. A. Meza–Herrera, F. Vaca–Paniagua, C. E. Díaz–Velásquez, L. M. Valenzuela–Núñez, V. Ávila–Rodríguez Pacheco–Torres, I., García–De la Peña, C., Aguillón–Gutiérrez, D. R., Meza–Herrera, C. A., Vaca–Paniagua, F., Díaz–Velásquez, C. E., Valenzuela–Núñez, L. M., Ávila–Rodríguez, V., 2019. First insights into the fecal bacte- rial microbiota of the black–tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) in Janos, Mexico. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 42.1: 127–134, Doi: https://doi.org/10.32800/abc.2019.42.0127 Abstract First insights into the fecal bacterial microbiota of the black–tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) in Janos, Mexico. Intestinal bacteria are an important indicator of the health of their host. Incorporating periodic assess- ment of the taxonomic composition of these microorganisms into management and conservation plans can be a valuable tool to detect changes that may jeopardize the survival of threatened populations. Here we describe the diversity and abundance of fecal bacteria for the black–tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), a threat- ened species, in the Janos Biosphere Reserve, Chihuahua, Mexico. We analyzed fecal samples through next generation massive sequencing and amplified the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using Illumina technology. The results were analyzed with QIIME based on the EzBioCloud reference. We identified 12 phyla, 22 classes, 33 orders, 54 families and 263 genera.