Spatial and Historical Determinants of Separatism and Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistisch Jaarboek 2003

Statistisch Jaarboek 2003 Statistisch Jaarboek 2003 - 1 - Statistisch Jaarboek 2003 Colofon Titel Statistisch Jaarboek 2003 Redactie Dick Bartelson Michel Franssen Antoon de Groot Ton de Kleijn Wilmar Kortleever Philip Krul Marjilde Prins Remko Riebeek Eindredactie en vormgeving Remko Riebeek Foto Omslag Soenar Chamid Koninklijke Nederlandse Atletiek Unie Floridalaan 2, 3404 WV IJsselstein Postbus 230, 3400 AE IJsselstein Telefoon (030) 6087300 Fax (030) 6043044 Internet: www.knau.nl E-mail KNAU: [email protected] E-mail werkgroep statistiek: [email protected] (voor correcties en aanvullingen) - 2 - Statistisch Jaarboek 2003 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave ............................................................................................................................... 3 Voorwoord ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Kroniek van het seizoen 2003 ........................................................................................................ 5 Een vergelijking ............................................................................................................................ 24 Nationale records gevestigd in 2003 ........................................................................................... 26 Nederlanders in de wereldranglijsten 2003 ................................................................................ 29 Kampioenschappen, interlands en (inter)nationale wedstrijden in Nederland ...................... -

9TOIDC COL 01R2.QXD (Page 1)

*TOID90603/ /01/K/1*/01/Y/1*/01/M/1*/01/C/1* New Delhi, Monday,June 9, 2003www.timesofindia.com Capital 42 pages* Invitation Price Rs. 1.50 International City Report Times Sport The Clintons sought If you’re chasing the Lara fails to marriage counselling good life, the suburbs save Windies after Monica affair are the place for you against Lanka Page 12 Page 2 Page 17 WIN WITH THE TIMES Down Under, Indians thunder Good news US looks to Monsoon arrives, many Established 1838 AP Kerala areas get good rainfall Bennett, Coleman & Co., Ltd. Dust haze blows over but Peace, prosperity, liberty Delhi rain only by month-end and morals have an intimate Coming connection. cash in on Rain over some southern soon and eastern states — Thomas Jefferson Advani visit Breathe easy, the rain has landed Focus on Iraq, military bases and is moving up By Chidanand Rajghatta Also on the table will be TIMES NEWS NETWORK TIMES NEWS NETWORK the issue of Indian military bases and training facilities New Delhi: The rain gods finally relent- Washington: A meeting for the US, amid a burgeon- ed, with the south-west monsoon hitting with the high priests of Pen- ing defence relationship that Kerala on Sunday, a week behind sched- tagon precedes one with the has already seen joint exer- ule. Several parts of the state reported pandas of Washington’s Dur- cises of the kind Washington ‘‘good rainfall’’. The advent of the mon- ga Temple for Deputy Prime usually reserves for its allies soon over Kerala seems to have brought Minister L K Advani, who ar- like Japan and South Korea. -

10Th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki (FIN) - Saturday, Aug 06, 2005 Shot Put - M QUALIFICATION Qual

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki (FIN) - Saturday, Aug 06, 2005 Shot Put - M QUALIFICATION Qual. rule: qualification standard 20.25m or at least best 12 qualified. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Group A 06 August 2005 - 10:00 Position Bib Athlete Country Mark . 1 971 Christian Cantwell USA 21.11 Q . 2 200 Joachim Olsen DEN 20.85 Q . 3 75 Andrei Mikhnevich BLR 20.54 Q . 4 1012Adam Nelson USA 20.35 Q . 5 304 Tepa Reinikainen FIN 20.19 q . 6 727 Tomasz Majewski POL 20.12 q . 7 363 Carl Myerscough GBR 20.07 q . 8 774 Gheorghe Guset ROU 19.83 . 9 239 Manuel Martínez ESP 19.55 . 10 194 Petr Stehlík CZE 19.48 . 11 853 Miran Vodovnik SLO 19.28 . 12 838 Ivan Yushkov RUS 18.98 . 13 143 Marco Antonio Verni CHI 18.60 . 14 509 Dorian Scott JAM 18.33 . 840 Shaka Sola SAM DNS . Athlete 1st 2nd 3rd Christian Cantwell 21.11 Joachim Olsen 20.16 19.82 20.85 Andrei Mikhnevich 20.54 Adam Nelson X 20.35 Tepa Reinikainen 19.87 20.19 20.06 Tomasz Majewski 20.04 20.12 20.09 Carl Myerscough 19.88 20.07 19.68 Gheorghe Guset 19.44 19.60 19.83 Manuel Martínez 19.49 19.55 19.28 Petr Stehlík 18.98 19.48 X Miran Vodovnik 18.60 18.58 19.28 Ivan Yushkov 18.77 18.98 X Marco Antonio Verni X X 18.60 Dorian Scott 18.10 X 18.33 Shaka Sola Group B 06 August 2005 - 10:00 Position Bib Athlete Country Mark . -

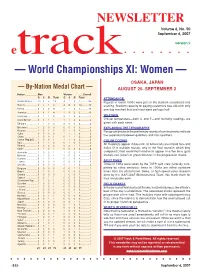

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No. 50 September 6, 2007 version ii etrack — World Championships XI: Women — OSAKA, JAPAN — By-Nation Medal Chart — AUGUST 25–SEPTEMBER 2 Nation ..................Men Women ......Overall G S B Total G S B Total ATTENDANCE United States .......10 3 6 19 4 1 2 7 ............26 Figures in round 1000s were put on the stadium scoreboard one Russia ..................0 1 1 2 4 8 2 14 ..........16 evening. Stadium capacity for paying customers was c36,000; only Kenya ..................3 2 3 8 2 1 2 5 ............13 one day reached that and most were perhaps half. Jamaica ...............0 3 1 4 1 3 2 6 ............10 Germany ..............0 1 1 2 2 1 2 5 ..............7 WEATHER Great Britain .........0 0 1 1 1 1 2 4 ..............5 Official temperature—both C and F—and humidity readings are Ethiopia ................1 1 0 2 2 0 0 2 ..............4 given with each event. Bahamas ..............1 2 0 3 0 0 0 0 ..............3 EXPLAINING THE TYPOGRAPHY Belarus ................1 0 1 2 0 1 0 1 ..............3 Paragraph breaks in the preliminary rounds of running events indicate Cuba ....................0 0 0 0 1 1 1 3 ..............3 the separation between qualifiers and non-qualifiers. China ...................1 0 0 1 0 1 1 2 ..............3 Czech Republic ....1 0 0 1 1 1 0 2 ..............3 COLOR CODING Italy ......................0 1 1 2 0 1 0 1 ..............3 All medalists appear in blue ink; all Americans are in bold face and Poland .................0 0 2 2 0 0 1 1 ..............3 Spain ...................0 1 0 1 0 0 2 2 ..............3 italics (if in multiple rounds, only in the final round in which they Australia ...............1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 ..............2 competed); field-event/multi medalists appear in either blue (gold Bahrain ................0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 ..............2 medal), red (silver) or green (bronze) in the progression charts. -

Qualification START LIST Hammer Throw WOMEN Karsintakilpailu

10th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki From Saturday 6 August to Sunday 14 August 2005 Hammer Throw WOMEN Moukarinheitto NAISET ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHL Qualification START LIST Karsintakilpailu OSANOTTAJALUETTELO ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETI Qualification standard 70.00 or at least best 12 qualified 1 2 Group A 10 August 2005 14:00 Ryhmä A START BIB COMPETITOR NAT YEAR Personal Best 2005 Best 1 567 Kamila SKOLIMOWSKA POL 82 74.27 74.27 2 300 Betty HEIDLER GER 83 72.73 72.19 3 7 Jennifer DAHLGREN ARG 84 67.07 67.07 4 231 Sini PÖYRY FIN 80 69.16 68.90 5 594 Mihaela MELINTE ROM 75 76.07 71.95 6 711 Cecilia NILSSON SWE 79 68.44 68.44 7 56 Darya PCHELNIK BLR 81 71.08 71.08 8 796 Bethany HART USA 77 69.65 69.65 9 122 Wenxiu ZHANG CHN 86 73.24 73.24 10 306 Kathrin KLAAS GER 84 70.91 70.91 11 648 Tatyana LYSENKO RUS 83 77.06 77.06 12 155 Yipsi MORENO CUB 80 75.18 73.88 13 350 Éva ORBÁN HUN 84 68.70 68.70 14 181 Berta CASTELLS ESP 84 68.87 68.31 15 770 Nataliya ZOLOTUKHINA UKR 85 69.73 67.75 16 638 Yekaterina KHOROSHIKH RUS 83 73.08 73.08 17 373 Clarissa CLARETTI ITA 80 70.59 70.59 Issued Tuesday, 09 August 2005 at 11:01 Timing and Measurement by SEIKO Data processing -

2014 European Championships Statistics – Women's 100M

2014 European Championships Statistics – Women’s 100m by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the European Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 10.73 2.0 Christine Arron FRA 1 Budapest 1998 2 10.81 1.3 Christine Arron 1sf1 Budapest 1998 3 2 10.83 2.0 Irina Privalova RUS 2 Budapest 1998 4 3 10.87 2.0 Ekaterini Thanou GRE 3 Budapest 1998 5 4 10.89 1.8 Katrin Krabbe GDR 1 Split 1990 6 5 10.91 0.8 Marlies Göhr GDR 1 Stuttgart 1986 7 10.92 0.9 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf2 Budapest 1998 7 6 10.92 2.0 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block UKR 4 Budapest 1998 9 10.98 1.2 Marlies Göhr 1sf2 Stuttgart 1986 10 11.00 1.3 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 2sf1 Budapest 1998 11 11.01 -0.5 Marlies Göhr 1 Athinai 1982 11 11.01 0.9 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 1h2 Helsinki 1994 13 11.02 0.6 Irina Privalova 1 Helsinki 1994 13 11.02 0.9 Irina Privalova 2sf2 Budapest 1998 15 7 11.04 0.8 Anelia Nuneva BUL 2 Stuttgart 1986 15 11.04 0.6 Ekaterini Thanou 1h4 Budapest 1998 17 8 11.05 1.2 Silke Gladisch -Möller GDR 2sf2 Stuttgart 1986 17 11.05 0.3 Ekaterini Thanou 1sf2 München 2002 19 11.06 -0.1 Marlies Göhr 1h2 Stuttgart 1986 19 11.06 -0.8 Zhanna Pintusevich -Block 1h1 Budapest 1998 19 9 11.06 1.8 Kim Gevaert BEL 1 Göteborg 2006 22 10 11.06 1.7 Ivet Lalova BUL 1h2 Helsinki 2012 22 11.07 0.0 Katrin Krabbe 1h1 Split 1990 22 11 11.07 2.0 Melanie Paschke GER 5 Budapest 1998 25 11.07 0.3 Ekaterini Thanou 1h4 München 2002 25 11.08 1.2 Anelia Nuneva 3sf2 Stuttga rt 1986 27 12 11.08 0.8 Nelli Cooman NED 3 Stuttgart 1986 28 11.09 0.8 Silke Gladisch -Möller -

Oliver Dietz Spurtet Zum Titel Tauchen Ab N Auftakt Der 104

Ihr Mitsubishi- Ansprechpartner in der Region Auto Schrader GmbH Mitsubishi-Vertragshändler Salzdahlumer Str. 74, BS Telefon 05 31/1 21 91-0 www.mitsubishi-braunschweig.de Anzeigen: 3 90 07 60 · Kleinanzeigen: 23 88 20 · Telefax: 3 90 07 53 · Redaktion: 3 90 07 50 H 48439 SONNTAG, 11. JULI 2004 AUFLAGE: 168 668 NR. 28 · 42. JAHRGANG Lange Nacht Judo: Heute Epoche voller im Jolly Joker geht es weiter Sinnlichkeit Mit mehreren hundert Gästen Mit Dimitri Peters startet „Barocke Leidenschaften“ heißt und Live-Musik (im Bild „Bos- heute ein weiterer BJC- das Festival zur Rubens-Ausstel- se“) feierte das Stadtmagazin Kämpfer bei den Internatio- lung. Bis Oktober gibt es Kultu- Subway die 200. Ausgabe. Die nalen Deutschen Judo-Ein- relles mit Bezug zum Braun- nB feierte mit. Mehr darüber zelmeisterschaften. Wie es schweiger Barock. Wir berich- auf Seite 24. Foto: Agentur T.A. gestern lief, steht im Sport. ten auf Seite 16. Foto: Museum FiBS: Kinder Oliver Dietz spurtet zum Titel tauchen ab n Auftakt der 104. Deutschen Leichtathletik-Meisterschaften gestern in Braunschweig (c). Kinder, die B Von Martina Jurk Braunschweig NEWS ihre Ferien zu Hause verbringen, können im Juli und August an Braunschweig. Am Ende mehreren Tauchschnupperkursen des ersten Wettkampftages des FiBS-Programms teilnehmen. Händler haben Mitmachen können alle Kinder ab mehr Freiheit war die Sensation perfekt: zehn Jahren. Bedingung ist, dass Oliver Dietz von der Leicht- sie schwimmen und eine ärztliche Die Zeiten eines einheitli- athletik-Gemeinschaft Bescheinigung über ihre Tauch- chen Sommerschlussverkau- Braunschweig wurde Deut- tauglichkeit vorweisen können. fes sind passé. „Der Handel scher Meister auf der Die Kurse kosten zehn Euro. -

2013 Shaping Change Imprint Published By: the President Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University of Applied Sciences

Shaping Change The University Addresses Society‘s Probing Challenges Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University of Applied Sciences Annual Report 2013 The University Addresses Society‘s Probing Challenges Society‘sProbing The UniversityAddresses 2013 Shaping Change Imprint Published by: The President Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University of Applied Sciences Editor (responsible): Eva Tritschler Executive Department of Marketing and Communications Content design and editing: Katja Spross, Nele van Leeuwen Trio MedienService, Bonn Translation: Marta Schuman en:comms, Bonn Layout and design: Bosse und Meinhard GbR Wissenschaftskommunikation, Bonn Printing: f & m Satz und Druckerei GmbH & Co. KG, Sankt Augustin Paper: BVS matt, FSC-certified Print run / Date: 1,400 / July 2014 Shaping Change The University Addresses Society’s Probing Challenges 4 Contents StudiumDialogue & Lehre Studies and Teaching Research Campus 6 12 24 38 Hartmut Ihne, President of Lecture series on technology DLR/NASA: Flying observatory Campus holds fi rst-ever Day Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University and environmental ethics • • Biology: Exploring the causes of Research • Coaching and of Applied Sciences, and Ralf Progressive learning in the of arthritis • Institute of Visual training for foreign students Stemmer, member of Post- Biochemical Science Master’s Computing receives research and graduates • Tips and bank’s Board of Management, programme • Learning English funding • IMEA and TREE: workshops for new students talk about digitalisation, through mock trade fairs New research institutes • women in -

Japão 25 De Agosto a 03 De Setembro De 2007

11º Campeonatos Mundiais de Atletismo Adulto Osaka – Japão 25 de agosto a 03 de setembro de 2007 Official Results - Marathon - M - Final 25 august 2007 - 7:00 Pos Bib Athlete Country Mark 1 15 Luke Kibet KEN 2:15:59 2 4 Mubarak Hassan Shami QAT 2:17:18 3 9 Viktor Röthlin SUI 2:17:25 4 73 Yared Asmerom ERI 2:17:41 5 29 Tsuyoshi Ogata JPN 2:17:42 (SB) 6 30 Satoshi Osaki JPN 2:18:06 (SB) 7 14 Toshinari Suwa JPN 2:18:35 (SB) 8 10 William Kiplagat KEN 2:19:21 9 49 Janne Holmén FIN 2:19:36 10 22 José Manuel Martínez ESP 2:20:25 11 59 Dan Robinson GBR 2:20:30 12 47 Alex Malinga UGA 2:20:36 13 33 Tomoyuki Sato JPN 2:20:53 14 8 Gashaw Asfaw ETH 2:20:58 15 79 Ju-Young Park KOR 2:21:49 16 56 Mike Fokoroni ZIM 2:21:52 17 18 José Ríos ESP 2:22:21 (SB) 18 60 José de Souza BRA 2:22:24 19 81 Seteng Ayele ISR 2:22:27 (SB) 20 66 Ali Mabrouk El Zaidi LBA 2:22:50 21 45 Mbarak Kipkorir Hussein USA 2:23:04 (SB) 22 50 Alberto Chaíça POR 2:23:22 (SB) 23 70 Mike Morgan USA 2:23:28 (SB) 24 76 Young Chun Kim KOR 2:24:25 25 27 Samson Ramadhani TAN 2:25:51 26 65 Myongseung Lee KOR 2:25:54 27 2 Hendrick Ramaala RSA 2:26:00 28 82 Chia-Che Chang TPE 2:26:22 29 75 Khalid Kamal Yaseen BRN 2:26:32 (SB) 30 28 Getuli Bayo TAN 2:26:56 31 12 Dejene Birhanu ETH 2:27:50 (SB) 32 72 Kyle O'Brien USA 2:28:28 (SB) 33 64 Wei Su CHN 2:28:41 (SB) 34 85 Wodage Zvadya ISR 2:29:21 35 54 Luís Feiteira POR 2:29:34 36 32 Haiyang Deng CHN 2:29:37 (SB) 37 86 Ulrich Steidl GER 2:30:03 38 17 Ambesse Tolosa ETH 2:30:20 39 78 Michael Tluway Mislay TAN 2:30:33 40 83 Asaf Bimro ISR 2:31:34 41 53 -

2002 V1.1 Statistisch Jaarboek.Pdf

Statistisch Jaarboek 2002 Statistisch Jaarboek 2002 - 1 - Statistisch Jaarboek 2002 Colofon Titel Statistisch Jaarboek 2002 Redactie Antoon de Groot Ton de Kleijn Wilmar Kortleever Philip Krul Remko Riebeek Anton Smeets Eindredactie en vormgeving Remko Riebeek Foto Soenar Chamid Koninklijke Nederlandse Atletiek Unie Floridalaan 2, 3404 WV IJsselstein Postbus 230, 3400 AE IJsselstein Telefoon (030) 6087300 Fax (030) 6043044 Internet: www.knau.nl E-mail KNAU: [email protected] E-mail Werkgroep Statistiek: [email protected] (voor correcties en aanvullingen) - 2 - Statistisch Jaarboek 2002 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave ............................................................................................................................... 3 Voorwoord ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Kroniek van het seizoen 2002 ........................................................................................................ 5 Nationale records gevestigd in 2002 ........................................................................................... 16 Nederlanders in de wereldranglijsten ......................................................................................... 19 Kampioenschappen, interlands en internationale wedstrijden ................................................ 21 Nederlandse Records ................................................................................................................... 64 Beste Prestaties ........................................................................................................................... -

2018 European Championships Statistics – Women’S HT by K Ken Nakamura

2018 European Championships Statistics – Women’s HT by K Ken Nakamura Summary All time Performance List at the European Championships Performance Performer Distance Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 78.76 Anit a Wlodarczyk POL 1 Zürich 2014 2 78.14 Anita Wlodarczyk 1 Amsterdam 2016 3 2 76.67 Tatyana Lysenko RUS 1 Göteborg 2006 4 3 76.38 Betty Heidler GER 1 Barcelona 2010 5 75.77 Betty Heidler 2 Amsterdam 2016 6 75.73 An it a Wlodarczxyk Q Zürich 2014 7 75.65 Tatyana Lysenko RUS 2 Barcelona 2010 8 4 74.66 Martina Hrasnova SVK 2 Zürich 2014 9 5 74.50 Gulfiya Khanafeyeva RUS 2 Göteborg 2006 10 74.29 Anita Wlodarczyk 1 Helsinki 2012 Margin of Victory Difference Distance Name Nat Venue Year Max 4.10m 78.76 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Zürich 2014 2.37m 78.14 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Amsterdam 2016 2.17m 76.67 Tatyana Lysenko RUS Göteborg 2006 Min 48cm 72.94 Olga Kuzenkova RUS München 2002 Best Marks for Places in the European Championships Pos Distance Name Nat Venue Year 1 78. 76 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Zürich 2014 78.14 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Amsterdam 2016 76.67 Tatyana Lysenko RUS Göteborg 2006 2 75.77 Betty Heidler GER Amsterdam 2016 75.65 Tatyana Lysenko RUS Barcelona 2010 3 73.83 Hanna Skydan AZE Amsterdam 2016 73.67 Joanna Fidorow POL Zürich 2014 73.56 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Barcelona 2010 4 72.89 Kathrin Klaas GER Zürich 2014 71.87 Maryna Smalyachkova BLR Göteborg 2006 Longest non-qualifier for the final Distance Position Name Nat Venue Year 67.78 13q Merja Korpela FIN Amsterdam 2016 66.51 6qA Katerina Safrankova CZE Helsinki 2012 66.45 7qA Susanne Keil GER -

Presse - Arbeitsblatt

118. Deutsche Meisterschaften 21./22. Juli 2018 in Nürnberg Presse - Arbeitsblatt Frauen - 800 m (Vorläufe Samstag 13.25 ; Endlauf Sonntag 18.05 Uhr) Die Teilnehmerinnen Rekorde, Bestleistungen, Normen Startnr. Name Jahrg. Verein Meldeleistung Rekorde: 314 Hering, Christina 1994 LG Sta. München 02:00,5 740 Schmidt, Sarah 1996 Bayer Leverkusen 02:02,2 Welt 1:53,28 Jarmila Kratochvilova 1983 794 Spill, Tanja 1995 Bayer Uerdingen/Do 02:02,3 Europa 1:53,28 Jarmila Kratochvilova 1983 1289 Klein, Hanna 1993 SG Schorndorf 02:02,4 Deutschland 1:55,26 Sigrun Wodars (Neubra.) 1987 335 Trost, Katharina 1995 LG Sta. München 02:02,6 DLV - U23: 1:55,26 Sigrun Wodars (Neubra.) 1987 665 Ackers, Rebekka 1990 Bayer Leverkusen 02:04,6 Meist.-Bestleist. 1:58,45 Hildegard Falck (Wolfsb.)1971 140 Granz, Caterina 1994 LG Nord Berlin 02:04,7 Stadionrekord 1:58,47 Hasna Benhassi (MAR) 2000 310 Gess, Christine 1994 LG Sta. München 02:04,8 31 Reinert, Jana 1998 LG Region Karlsruhe 02:05,1 Jahresbestleistungen: 611 Hoffmann, Vera 1996 ASV Köln 02:06,0 Welt 1:54,25 Caster Semenya (Südafrika) 284 Kohlmann, Corinne 1994 LG Karlstadt/G./L. 02:06,6 Europa 1:59,09 Laura Muir (Großbritannien) 182 Weßel, Nele 1999 SCC Berlin 02:06,7 Deutschland 2:00,48 Christina Hering (München) 315 Kalis, Mareen 1997 LG Sta. München 02:07,2 699 Klaassen, Lena 1991 Bayer Leverkusen 02:07,4 148 Kuhn, Isabella 1996 LG Nord Berlin 02:08,6 Normen / Qualifikationsleistungen: 940 Noack, Celine 1998 Dresdner SC 02:08,9 EM-Norm 2:01,50 min 1056 Hansen, Laura 1990 LG Oly.