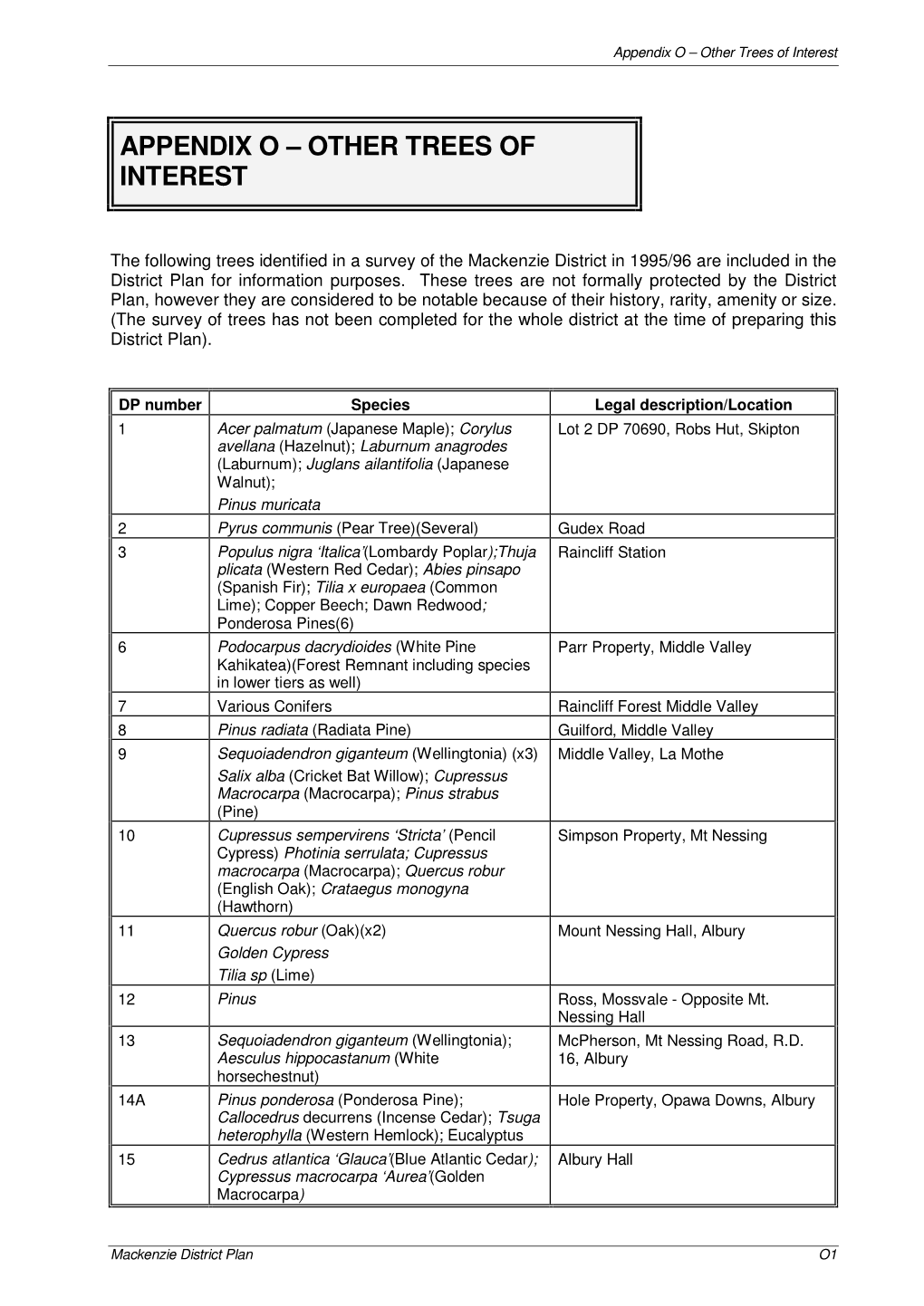

Appendix O – Other Trees of Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying Species and Hybrids in the Genus Juglans by Biochemical Profiling of Bark

ISSN 2226-3063 e-ISSN 2227-9555 Modern Phytomorphology 14: 27–34, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.200108 RESEARCH ARTICLE Identifying species and hybrids in the genus juglans by biochemical profiling of bark А. F. Likhanov *, R. I. Burda, S. N. Koniakin, M. S. Kozyr Institute for Evolutionary Ecology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 37, Lebedeva Str., Kyiv 03143, Ukraine; * likhanov. [email protected] Received: 30. 11. 2019 | Accepted: 23. 12. 2019 | Published: 02. 01. 2020 Abstract The biochemical profiling of flavonoids in the bark of winter shoots was conducted with the purpose of ecological management of implicit environmental threats of invasions of the species of the genus Juglans and their hybrids under naturalization. Six species of Juglans, introduced into forests and parks of Kyiv, were studied, namely, J. ailantifolia Carrière, J. cinerea L., J. mandshurica Maxim., J. nigra L., J. regia L., and J. subcordiformis Dode, cultivar J. regia var. maxima DC. ′Dessert′ and four probable hybrids (♀J. subcordiformis × ♂J. ailantifolia; ♀J. nigra × ♂J. mandshurica; ♀J. cinerea × ♂J. regia and ♀J. regia × ♂J. mandshurica). Due to the targeted introduction of different duration, the invasive species are at the beginning stage of forming their populations, sometimes amounting to naturalization. The species-wise specificity of introduced representatives of different ages (from one-year-old seedlings to generative trees), belonging to the genus Juglans, was determined. J. regia and J. nigra are the richest in the content of secondary metabolites; J. cinerea and J. mandshurica have a medium level, and J. ailantifolia and J. subcordiformis-a low level. On the contrary, the representatives of J. -

Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids

Purdue University Purdue extension FNR-420-W & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Identification of Butternuts and Butternut Hybrids Lenny Farlee1,3, Keith Woeste1, Michael Ostry2, James McKenna1 and Sally Weeks3 1 USDA Forest Service Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY 2 USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, 1561 Lindig Ave. St. Paul, MN 55108 3 Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, 715 W. State Street, West Lafayette, IN, 47907 Introduction Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as white walnut, is a native hardwood related to black walnut (Juglans nigra) and other members of the walnut family. Butternut is a medium-sized tree with alternate, pinnately compound leaves that bears large, sharply ridged and corrugated, elongated, cylindrical nuts born inside sticky green hulls that earned it the nickname lemon-nut (Rink, 1990). The nuts are a preferred food of squirrels and other wildlife. Butternuts were collected and eaten by Native Americans (Waugh, 1916; Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975) and early settlers, who also valued butternut for its workable, medium brown-colored wood (Kellogg, 1919), and as a source of medicine (Johnson, 1884), dyes (Hamel and Chiltoskey, 1975), and sap sugar. Butternut’s native range extends over the entire north- eastern quarter of the United States, including many states immediately west of the Mississippi River, and into Canada. Butternut is more cold-tolerant than black walnut, and it grows as far north as the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and Figure 1. -

Podocarpus Totara

Mike Marden and Chris Phillips [email protected] TTotaraotara Podocarpus totara INTRODUCTION AND METHODS Reasons for planting native trees include the enhancement of plant and animal biodiversity for conservation, establishment of a native cover on erosion-prone sites, improvement of water quality by revegetation of riparian areas and management for production of high quality timber. Signifi cant areas of the New Zealand landscape, both urban and rural, are being re-vegetated using native species. Many such plantings are on open sites where the aim is to quickly achieve canopy closure and often includes the planting of a mixture of shrubs and tree species concurrently. Previously, data have been presented showing the potential above- and below-ground growth performance of eleven native plant species considered typical early colonisers of bare ground, particularly in riparian areas (http://icm.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/land/Trial1results.asp). In this current series of posters we present data on the growth performance of six native conifer (kauri, rimu, totara, matai, miro, kahikatea) and two broadleaved hardwood (puriri, titoki) species most likely to succeed the early colonising species to become a major component in mature stands of indigenous forest (http://icm.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/land/ Trial2.asp). Data on the potential above- and below-ground early growth performance of colonising shrubby species together with that of conifer and broadleaved species will help land managers and community groups involved in re-vegetation projects in deciding the plant spacing and species mix most appropriate for the scale of planting and best suited to site conditions. Data are from a trial established in 2006 to assess the relative growth performance of native conifer and broadleaved hardwood tree species. -

The New Zealand Beeches : Establishment, Growth and Management / Mark Smale, David Bergin and Greg Steward, Photography by Ian Platt

Mark Smale, David K ....,.,. and Greg ~t:~·wa11.r Photography by lan P Reproduction of material in this Bulletin for non-commercial purposes is welcomed, providing there is appropriate acknowledgment of its source. To obtain further copies of this publication, or for information about other publications, please contact: Publications Officer Private Bag 3020 Rotorua New Zealand Telephone: +64 7 343 5899 Fac.rimile: +64 7 348 0952 E-nraif. publications@scionresearch .com !Pebsite: www.scionresearch.com National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication data The New Zealand beeches : establishment, growth and management / Mark Smale, David Bergin and Greg Steward, Photography by Ian Platt. (New Zealand Indigenous Tree Bulletin, 1176-2632; no.6) Includes bibliographic references. 978-0-478-11018-0 1. trees. 2. Forest management-New Zealand. 3. Forests and forestry-New Zealand. 1. Smale, Mark, 1954- ll. Bergin, David, 1954- ill. Steward, Greg, 1961- IV. Series. V. New Zealand Forese Research Institute. 634.90993-dc 22 lSSN 1176-2632 ISBN 978-0-478-11038-3 ©New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited 2012 Production Team Teresa McConcbie, Natural Talent Design - design and layout Ian Platt- photography Sarah Davies, Richard Moberly, Scion - printing and production Paul Charters - editing DISCLAIMER In producing this Bulletin reasonable care has been taAren lo mmre tbat all statements represent the best infornJation available. Ht~~vever, tbe contents of this pt1blicatio11 are not i11tended to be a substitute for s,Pecific specialist advice on at!} matter and should not be relied on for that pury~ose. NEW ZEALAND FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE L!JWJTED mtd its emplqyees shall not be liable on at.ry ground for a'!)l lost, damage, or liabili!J inrorred as a direct or indirect result of at!J reliance l{y a'!)l person upon informatiou contained or opinions expressed in this tvork. -

Acceptable Replacement Trees

October 2000 BUILDING DIVISION Bulletin No. T-2 Acceptable Replacement Trees Acceptable Replacement Trees (other than Boulevard Replacement Trees) The following table lists acceptable replacement tree species and sizes. All plant material and planting techniques must comply with the latest edition of the BCSLA/BCNTA "Landscape Standard" City of Surrey Planning & Development Department, 14245 - 56 Avenue, Surrey, B.C. V3X 3A2 Telephone: 591-4441 City of Surrey Planning & Development Department REPLACEMENT TREES NOTES TO THE TABLE: (1) IN THE MINIMUM SIZE COLUMN, REFERENCE TO A FIGURE IN CENTIMETRES (cm) IS A MEASUREMENT OF TRUNK DIAMETER 15 cm ABOVE THE GROUND. REFERENCE TO A FIGURE IN METRES (m) IS A MEA- SUREMENT OF HEIGHT ABOVE THE GROUND. (2) THE COLUMN HEADING TYPE, L = LARGE, M = MEDIUM, S = SMALL AND F = FASTIGIATE (OR COLUMNAR) AND REFERS TO THE SIZE OF TREE AT MATURITY, NOT THE SIZE WHEN PLANTED. COMMON NAME BOTANICAL NAME PLANTING SIZE TYPE Hedge MapleAcer campestre Queen Elizabeth5 cm caliperS Vine Maple Acer circinatum 5 cm caliper S Amur Maple Acer ginnala 5 cm caliper S Bloodgood Japanese Maple Acer palmatum Bloodgood 5 cm caliper S Globe Maple Acer platanoides Globosum 5 cm caliper S Youngs Weeping Birch Betula pendula Youngii 5 cm caliper S Hackberry Celtis occidentalis 5 cm caliper S Eastern Redbud Cercis canadensis 5 cm caliper S Eddies White Wonder Dogwood Cornus Eddies White Wonder 5 cm caliper S Chinese Dogwood Cornus chinensis 5 cm caliper S Kousa Dogwood Cornus kousa 3 m height S Cornelian Cherry Cornus mas 3 m height -

Here Before We Humans Were and Their Relatives Will Probably Be Here When We Are Gone

The ‘mighty tōtara’ is one of our most extraordinary trees. Among the biggest and oldest trees in the New Zealand forest, the heart of Māori carving and culture, trailing no. 8 wire as fence posts on settler farms, clambered up in the Pureora protests of the 1980s: the story of New Zealand can be told through tōtara. Simpson tells that story like nobody else could. In words and pictures, through waka and leaves, farmers and carvers, he takes us deep inside the trees: their botany and evolution, their role in Māori life and lore, their uses by Pākehā, and their current status in our environment and culture. By doing so, Simpson illuminates the natural world and the story of Māori and Pākehā in this country. Our largest trees, the kauri Tāne Mahuta and the tōtara Pouakani, are both thought to be around 1000 years old. They were here before we humans were and their relatives will probably be here when we are gone. Tōtara has been central to life in this country for thousands of years. This book tells a great tree’s story, and that is our story too. Philip Simpson is a botanist and author of Dancing Leaves: The Story of New Zealand’s Cabbage Tree, Tī Kōuka (Canterbury University Press, 2000) and Pōhutukawa and Rātā: New Zealand’s Iron-hearted Trees (Te Papa Press, 2005). Both books won Montana Book Awards in the Environment category and Pōhutukawa and Rātā also won the Montana Medal for best non-fiction book. Simpson is unique in his ability to combine the scientific expertise of the trained botanist with a writer’s ability to understand the history of Māori and Pākehā interactions with the environment. -

An Economic Assessment of Radiata Pine, Rimu, and Mānuka

Pizzirani et al. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science (2019) 49:5 https://doi.org/10.33494/nzjfs492019x44x E-ISSN: 1179-5395 Published on-line: 20 June 2019 Research Article Open Access New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science Exploring forestry options with Māori landowners: an economic assessment of radiata pine, rimu, and mānuka Stefania Pizzirani*1,2,3, Juan J. Monge1, Peter Hall1, Gregory A. Steward1, Les Dowling1, Phil Caskey4, Sarah J. McLaren2,3 1 Scion, 49 Sala Street, Rotorua, 3046, New Zealand 2 Massey University, Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 3 New Zealand Life Cycle Management Centre, Massey University, Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 4 New Zealand Mānuka Group, 525b State Highway 30, Awakeri, Whakatane, 3191, New Zealand *corresponding author: Stefania Pizzirani: [email protected] (Received for publication 9 November 2017; accepted in revised form 6 May 2019) Abstract Background: A quarter of New Zealand’s land area is currently covered in indigenous forest although only indigenous forests on private land can be harvested. In addition, planted exotic forests (~90% Pinus radiata D.Don) cover a further 7% of the land, and these form the main basis of New Zealand’s forestry industry. However, some landowners are seeking to plant a more diverse range of species (including New Zealand indigenous species) that can be managed in different ways to produce a range of products. Methods: A “cradle-to-gate” life cycle-based economic assessment of three forestry scenarios was undertaken in (i.e. intensive management of radiata pine); (2) continuous-cover forestry management of the indigenous coniferous tree speciescollaboration rimu ( withDacrydium members cupressinum of Ngāti Porou, Lamb.); an and indigenous (3) intensive Māori production-scale tribe. -

An Updated List of Species Used in Tree-Ring Research

TREE-RING BULLETIN, Vol. 53, 1993 AN UPDATED LIST OF SPECIES USED IN TREE-RING RESEARCH HENRI D. GRISSINO-MAYER Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721, U.S.A. ABSTRACT During the past 100 years, researchers have investigated the potential of hundreds of tree and shrub species for use in applications of tree-ring research. Although several lists of species known to crossdate have been published, investigated species that do not crossdate are rarely included despite the usefulness of this infonnation for future research. This paper provides a list of the Latin and common names of 573 species that have been investigated in tree-ring research, infor mation on species known to crossdate, and information on species with measurement and/or chronology data in the International Tree-Ring Data Bank. In addition, a measure of the suitability of a species for future tree-ring applications, the Crossdating Index (CDI), is developed and pro posed for standard usage. 1n den letzten hundert J ahren haben Forscher das Potential von hunderten von Baum- und Buscharten fi.ir die Anwendung in der Jahresring-Forschung untersucht. Zahlreiche Listen mit Arten, von denen man wei~, da~ sie zeitlich korrespondieren, sind bereits veroffentlicht worden, dagegen sind untersuchte Arten, die nicht zeitlich korresponclieren, selten in Publikationen beriick sichtigt worden, obwohl diese Informationen fi.ir die kiinftige Forschung nutzvoll sein konnten. Dieser Artikel legt eine Liste der lateinischen und der gemeinen Narnen von 573 Arten vor, die im Rahmen der Jahresring-Forschung untersucht worden sind, Inforrnationen Uber Arten, die bekan nterweise zeitlich korrespondieren sowie Informationen iiber Arten mit Ma~- und/oder Chronologiedaten in der intemationalen Jahresring-Datenbank (International Tree-Ring Data Bank). -

Heartnut Farming for Profit

Heartnut Farming for Profit Planning Your Orchard Regardless if you are looking for land to plant heartnut trees, Juglans ailantifolia var. cordiformis or you already own land, you need to be aware of the climate, soil and the conditions and where heartnut trees will flourish. You must focus on the hardiness and suitability requirements of your climatic region. Heartnut trees are originally from Japan, a humid, temperate maritime climate, so they will do best in a similar North American climatic region. That characteristic places them in a zone 6-7, near a large body of water, where moderated winter conditions and a degree of spring frost protection exist. Over the millennia the heartnut’s cousin, the native black walnut has adapted to the North American climate extremes. The heartnut in its gentler maritime climate has never needed to adapt with a thick outer bark to resist cold and south-west injury. All walnut species bear their female flowers in the terminal buds. The terminal buds leaf out first in the spring ahead of the lateral buds, exposing them to injury from late spring frosts. Black walnut has survived because it has evolved the practise of leafing out 2-3 weeks later than most other wild trees, including the Japanese heartnut, and so avoiding damage to flower buds. We generally recommend planting seedling Chinese chestnut trees (grown from seed and not cloned). The heartnut is an exception. The more usual Japanese walnut Juglans ailantifolia, has a nut shaped more like a black walnut, round and poor cracking. Occasionally, this species has evolved off-spring that produces a more flattened nut that takes on the shape of a valentine heart and so the name, heartnut. -

Totara Cover Front

DISCLAIMER In producing this Bulletin reasonable care has been taken to ensure that all statements represent the best information available. However, the contents of this publication are not intended to be a substitute for specific specialist advice on any matter and should not be relied on for that purpose. NEW ZEALAND FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE LIMITED and its employees shall not be liable on any ground for any loss, damage, or liability incurred as a direct or indirect result of any reliance by any person upon information contained or opinions expressed in this work. To obtain further copies of this publication, or for information about Forest Research publications, please contact: Publications Officer Forest Research Private Bag 3020 Rotorua New Zealand telephone: +64 7 343 5899 facsimile: +64 7 343 5897 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.forestresearch.co.nz National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication data Bergin, D.O. (David O.) Totara establishment, growth, and management / David Bergin. (New Zealand Indigenous Tree Bulletin, 1176-2632; No.1) Includes bibliographic references. ISBN 0-478-11008-1 1. Podocarpus—New Zealand. 2. Forest management—New Zealand. I. New Zealand Forest Research Institute. II. Title. 585.3—dc 21 Production Team Jonathan Barran — photography Teresa McConchie — layout design John Smith — graphics Ruth Gadgil — technical editing Judy Griffith — editing and layout ISSN 1176-2632 ISBN 0-478-11008-1 © New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited 2003 Front cover insert: Emergent totara and younger trees along the forest edge in Pureora Forest Park, with mixed shrub species edging the picnic area in the foreground. -

Juglans Cinerea L

R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E ABSTRACT: To mitigate the loss of native tree species threatened by non-native pathogens, managers need to better understand the conservation status of remaining populations and the conditions that favor successful regeneration. Populations of Juglans cinerea L. (butternut), a wide-ranging riparian species, • have been devastated by butternut canker, a disease caused by a non-native fungal pathogen. We as- sessed J. cinerea within Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP) to determine post-disease survivorship and health, recruitment history, environmental conditions associated with survival, and the Conservation Status extent of hybridization with a non-native congener. Monitoring records were used to locate and collect data for 207 J. cinerea trees in 19 watersheds. Tree cores were collected from a subset of individuals to of a Threatened Tree assess recruitment history. We sampled vegetation plots within areas that contained J. cinerea to assess site conditions and overstory species composition of characteristic habitat. We collected leaf samples for Species: Establishing genetic analysis to determine the frequency of hybridization. Our reassessment of monitoring records suggests that J. cinerea abundance in GSMNP has declined due to butternut canker and thirty years of a Baseline for poor regeneration. Populations displayed continuous recruitment following Park establishment (1934) until around 1980, after which regeneration declined drastically. Ordination analysis revealed that J. Restoration of Juglans cinerea in the contemporary forest was associated with greater distance from homesites and reduced basal area of competing species. Hybrids comprised a small portion of sampled trees. The presence of cinerea L. -

An Investigation Into the Viability of Small-Scale Heartnut (Juglans Ailantifolia Var. Cordifomis) Production in the United Kingdom

An investigation into the viability of small-scale heartnut (Juglans ailantifolia var. cordifomis) production in the United Kingdom Elizabeth Mary Crossland Student number: 23511028 Word count: 9,986 Date: April 2013 BSc in Environmental Science Faculty of Engineering and the Environment University of Southampton Abstract Increasing global average temperature and population highlight the need for agricultural methods that are both productive and address climate change. Pressure to find sustainable food systems has led to increased research into agroforestry; an agricultural practice where trees, crops and livestock are integrated to produce multiple outputs and ecological benefits. Nut trees are often used within agroforestry systems and yield a protein-rich, high value crop. The heartnut (Juglans ailantifolia var. cordifomis) belonging to the walnut family, Juglandaceae, originates from Japan. Due to its quick growth, disease resistance and large yields, the heartnut may prove better adapted to the UK than currently grown nut trees. However, little is known about the climate suitability, grower adoption and consumer opinion of the heartnut. This study identifies the optimal areas for heartnut establishment with consideration of climate scenarios for 2080 using climatic mapping, the difficulties and benefits to nut crop adoption through nut grower interviews, and potential markets for the heartnut through consumer surveys. Coastal regions in mid to southern Scotland, western inland areas of Ireland, east Wales and mid areas of England, were found to be most suitable for heartnut establishment. The main factors in nut crop adoption were identified to be access to technical and financial resources, pests, farm structure, cost and diversification. Although no overall consumer preference for the heartnut was identified, the heartnut received a positive response from participants.