Tarot‟S Fascination with Egypt Helen S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tarot De Marseille – Type 2

The International Playing-Card Society PATTERN SHEET 002 Suit System IT Other Classification Recommended name: According to Depaulis (2013) the distinguishing Tarot de Marseille, Type II cards for the Type II of the Tarot de Marseille Alternative name: Tarot of Marseille(s) are: The Fool is called ‘LE MAT’, Trump IIII (Emperor) has no Arabic figure, Trump V History (Pope) has a papal cross, Trump VI (Love): In The Game of Tarot (1980) Michael Dummett Cupid flies from left to right, he has open eyes, has outlined three variant traditions for Tarot in and curly hair, Trump VII (Chariot): the canopy Italy, that differ in the order of the highest is topped with a kind of stage curtain, Trump trumps, and in grouping the virtues together or VIII (Justice): the wings have become the back not. He has called these three traditions A, B, and of the throne, Trump XV (Devil): the Devil’s C. A is centered on Florence and Bologna, B on belly is empty, his wings are smaller, Trump Ferrara, and C on Milan. It is from Milan that the XVI (Tower): the flames go from the Sun to the so-called Tarot de Marseille stems. This standard tower, Trump XVIII (Moon) is seen in profile, pattern seems to have flourished in France in the as a crescent, Trump XXI (World): the central 17th and 18th centuries, perhaps first in Lyon figure is a young naked dancing female, just (not Marseille!), before spreading to large parts dressed with a floating (red) scarf, her breast and of France, Switzerland, and later to Northern hips are rounded, her left leg tucked up. -

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival I first encountered the evocative images of the tarot, as no doubt many others have done, in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. This led to Pamela Coleman Smith’s tarot deck, and from there to the idiosyncratic writings of A.E. Waite with its musings on the Grail, on ‘secret doctrines’ and on the nature of mystical experience. Revival of interest in the tarot and the proliferation of tarot decks attests to the vibrancy of this phenomenon which appeared in the context of the eighteenth century occult revival. The subject is extensive, but my topic for now is the development of the tarot cards as a secret tradition legend in Britain from the late 1880’s to the 1930’s. (1) During this period, ideas about the nature of culture drawn from folklore and anthropological theory combined with ideas about the origins of Arthurian literature and with speculations about the occult nature of the tarot. These factors working together created an esoteric and pseudo-academic legend about the tarot as secret tradition. The most recent scholarly work indicates that tarot cards first appeared in Italy in the fifteenth century, while speculations about their occult meaning formed part of the French occult revival in the late eighteenth century. (Dummett 1980, 1996 ) The most authoritative historian of tarot cards, the philosopher Michael Dummett, is dismissive of occult and divinatory interpretations. Undoubtedly, as this excellent works points out, ideas about the antiquity of tarot cards are dependent on assumptions made at a later period, and there is a tendency among popular books to repeat each other rather than use primary sources. -

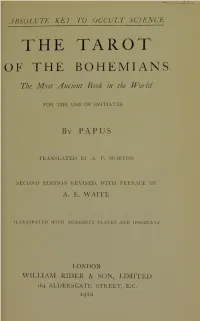

The Tarot of the Bohemians : the Most Ancient Book in the World

IBSOLUTE KET TO OCCULT SCIENCE THE TAROT ÜF THE BOHEMIANS The Most Ancient Book in the World FOR THE USE OF INITIATES By papus TRANSLATED BY A. P. MORTON SECOND EDITION REVISED, WITH PREFACE B Y A. E. WAITE ILLUSTRATED WITH N UMEROU S PLATES AND WOODCUTS LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LIMITED 164 ALDERSGATE STREET, E.C. 1910 Absolute Key to Oocult Science Frontispicce 2) BVÜ W Wellcome Libraty i forthe Histôry standing Il and ififcteï -, of Medi Printed by Ballantyne, HANSON &* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION An assumption of some kind being of common con- venience, that the line of least résistance may be pursued thereafter, I will open the présent considéra- tion by assuming that those who are quite unversed in the subject hâve referred to the pages which follow, and hâve thus become aware that the Tarot, on its external of that, side, is the probable progenitor playing-cards ; like these, it has been used for divination and for ail but that behind that is understood by fortune-telling ; this it is held to hâve a higher interest and another quality of importance. On a simple understanding, it is of allegory; it is of symbolism, on a higher plane; and, in fine, it is of se.cret doctrine very curiously veiled. The justification of these views is a different question; I am concerned wit>h ihe statement of fact are and this being said, I can that such views held ; pass to my real business, which" is in part critical and in part also explanatory, though not exactly on the elementary side. -

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

Tarot Reading Style: Healer Tarot Reading Style: Healing

Tarot Reading Style: Healer Tarot Reading Style: Healing USING YOUR NATURAL GIFTS & ABILITIES... You help people connect with the core energy of their obstacles and shift them into opportunities. You help them find tools to heal from the pain carried around from past relationships and situations. YOUR GREATEST TOOL IN TAROT READING IS... Resolving Past Issues In your readings, you bring focus and awareness to bringing harmony, balance, and alignment to all levels of being (mind, body, & spirit) and help your clients move through past blocks and baggage. Major Arcana Archetype Temperance Temperance reminds us that real change takes time ,A person's ability to exercise patience, balance, and self-control are infinite virtues. Temperance represents someone who has a patient, harmonious approach to life and understands the value of compromise. A READER WITH THIS ARCHETYPE: ... is able to guide people into a place of healing, where they begin to release the past. Because of their natural gift for diplomacy, they tend to be excellent communicators who bring out the best in their clients and friends. They could be holistic healers or have other psychic abilities and are able to combine different aspects of any modality in order to create something new and fresh. Your Strengths Healing HEALERS HAVE A NATURAL TALENT FOR SEEING 'CAUSE & EFFECT' ... Highlighting Connecting Patterns & Symptoms Limiting to Beliefs Experiences Easily See How It Plays Out In Clients Lives ... You focus on creating balance and harmony in your clients lives. ... You help them move out of the past by helping them revise and reframe it. ... You honor your clients pain and create the space for them to move through it. -

Genii Session 2007-12 Brief Updated History Of

Genii Session By Roberto Giobbi A Brief Updated History of Playing Cards When I published the German version of Card College Volume 1 in 1992, I included a short essay on the history of playing cards. In later editions I expanded on it and made a few corrections, among other smaller things I had committed a bigger mistake, namely that of assuming that today’s playing cards originated from tarot cards. The truth, as so often, is exactly the opposite, because playing cards were already in use in Europe in the second half of the 14th century whereas the game of Tarocchi and with it the Tarot cards was only invented in the first part of the 15th century in Italy. These mistakes were corrected in later editions of Card College and I’m therefore publishing this updated version of my essay for the benefit of all those who have the first few editions (we now have about 19,000 copies of Card College Volume 1 in the market). At the end of the essay I have also added a small annotated bibliography for all who would like to obtain more information about playing cards, their history, use, symbolism etc., a most fascinating subject. Rather than calling playing cards a prop, as it is often done in the literature, I would like to consider them to be an instrument of the card conjurer, like the piano or the violin is an instrument to a musician, and I would even dare saying that cards are the most important and most widely used instrument in all of conjuring. -

Witch Hunting

LE TAROT- ISTITUTO GRAF p resen t WITCH HUNTING C U R A T O R S FRANCO CARDINI - ANDREA VITALI GUGLIELMO INVERNIZZI - GIORDANO BERTI 1 HISTORICAL PRESENTATION “The sleep of reason produces monsters" this is the title of a work of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya. He portrayed a man sleeping on a large stone, while around him there were all kinds of nightmares, who become living beings. With this allegory, Goya was referring to tragedies that involved Europe in his time, the end of the eighteenth century. But the same image can be the emblem of other tragedies closer to our days, nightmares born from intolerance, incomprehension of different people, from the illusion of intellectual, religious or racial superiority. The history of the witch hunting is an example of how an ancient nightmare is recurring over the centuries in different forms. In times of crisis, it is seeking a scapegoat for the evils that afflict society. So "the other", the incarnation of evil, must be isolated and eliminated. This irrational attitude common to primitive cultures to the so-called "civilization" modern and post-modern. The witch hunting was break out in different locations of Western Europe, between the Middle Ages and the Baroque age. The most affected areas were still dominated by particular cultures or on the border between nations in conflict for religious reasons or for political interests. Subtly, the rulers of this or that nation shake the specter of invisible and diabolical enemy to unleash fear and consequent reaction: the denunciation, persecution, extermination of witches. -

Wayward Dark Tarot Book.Pdf

Wayward Dark Tarot “Your vision will become clear only when you can look into your own heart. Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.” -Carl Jung In the imagery of the Wayward Dark Tarot are the archetypes and symbolism of Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Tarot deck, mirrored and modified into a chthonic afterlife evoking the beautiful and the macabre. Familiarity with the Thoth Tarot will give you additional insight (and likely, additional critiques) of the Wayward Dark Tarot. Yet it should read on its own strengths as well. As it may be considered a fun house mirror of the Thoth deck, it is the same for your own inner thoughts and imagination. Look to the cards and you might discover a path to your subconscious paved through the archetypes of the Tarot. “Let the inner god that is in each one of us speak. The temple is your body, and the priest is your heart: it is from here that every awareness must begin.” -Alejandro Jodorowsky There are many ways to use a Tarot Deck. It can be for card games like tarocchini, occult purposes like divination, and in pursuing improvement through self-reflection and self-work. There is no right and wrong way to use your deck, just so long as the way you use it is a way that works for you. This book provides card keywords and meanings for your own clarity. If you have a stronger association with a card that contradicts the meanings given here, then go by your own interpretation. Above all, this book is meant to be a helpful guide, not a dictator. -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1915

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIQK FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY .GEORGE OTIS SMITH,' Director Water-Supply Paper 414 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1915 PAET XII. NORTH PACIFIC DRAINAGE BASINS C. LOWJEE COLUMBIA EIYEE AND PACIFIC DEAETAGE BATONS IN OEEGON NATHAN C. GROVER, Chief Hydraulic Engineer F. F. HENSHAW and G. L. PARKER, District Engineers Prepared in cooperation with the States of OREGON AND WASHINGTON WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 1918 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION' MAY BE PBOCURED FEOM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVEENMENT FEINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 20 CENTS PER COPY V CONTENTS. Page. Authorization and scope of work........................................... 7 Definition of terms. .........................................*............. 8 Convenient equivalents.................................................. 9 Explanation of data.................................................... 11 Accuracy of field data and computed results................................ 13 Cooperation.............................................................. 14 Division of work........................................................... 15 GagingHStation records. ....... .«....................-.................:... 15 Columbia River at The Dalles, Oreg................................... , 15 Tributaries of Columbia River below mouth of Snake River............ 17 Walla Walla River basin........................................... 17 South Fork of Walla Walla River near Milton, Oreg............. -

Spirit Keeper's Tarot, Marseille, RWS, and Thoth Correspondences

SKT, TDM, RWS, AND THOTH TAROT KEY CORRESPONDENCES (By Standardized Order) Major Arcana 22 Keys Spirit Keeper’s Tarot Tarot de Marseilles Rider-Waite-Smith Thoth (SKT) (TdM) (RWS) 0: The Initiate 0: The Fool 0: The Fool 0: The Fool 0: The Seeker 0: The Keeper 1: The Magus I: The Magician I: The Magician I: The Magus (or The Juggler) (or The Juggler) 2: The Priestess II: The Popess II: The High Priestess II: The Priestess (or The High Priestess) 3: The Empress III: The Empress III: The Empress III: The Empress 4: The Emperor IV: The Emperor IV: The Emperor IV: The Emperor 5: The Holy See V: The Pope V: The Hierophant V: The Hierophant 6: The Lovers VI: The Lovers VI: The Lovers VI: The Lovers (or The Brothers) 7: The Chariot VII: The Chariot VII: The Chariot VII: The Chariot 8: The Force VIII: Justice VIII: Strength VIII: Adjustment [XI: Strength] [XI: Lust] 9: The Erudite IX: The Hermit IX: The Hermit IX: The Hermit 10: Wheel of Life X: The Wheel of X: Wheel of Fortune X: Fortune Fortune 11: The Chancellor XI: Strength XI: Justice XI: Lust [VIII: Justice] [VIII: Adjustment] Page 1 of 12 SKT: TdM, RWS, and Thoth Key Correspondences By Standardized Order Spirit Keeper’s Tarot Tarot de Marseilles Rider-Waite-Smith Thoth (SKT) (TdM) (RWS) 12: The Outlaw XII: The Hanged Man XII: The Hanged Man XII: The Hanged Man 13: The Reaper XIII: Death XIII: Death XIII: Death (Untitled) 14: The Angel XIV: Temperance XIV: Temperance XIV: Art 15: The Demon XV: The Devil XV: The Devil XV: The Devil 16: The Tower XVI: The Tower XVI: The Tower XVI: The Tower -

Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.) Ellen P

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-13-2014 Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.) Ellen P. Randolph Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14110766 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Randolph, Ellen P., "Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.)" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1686. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1686 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida GNOSTICISM, TRANSFORMATION, AND THE ROLE OF THE FEMININE IN THE GNOSTIC MASS OF THE ECCLESIA GNOSTICA CATHOLICA (E.G.C.) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Ellen P. Randolph 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Ellen P. Randolph, and entitled Gnosticism, Transformation, and the Role of the Feminine in the Gnostic Mass of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (E.G.C.), having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

An Essay Upon Number

An Essay Upon Number by Frater Hoor Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. CONTENTS Page 1. The Great Undefined 11 2. “Thelemic” Mathematics 5 3. The Enochian System and the English Alphabet 8 4. A Brief Analysis of The Book of the Law 11 Chapter One 11 Chapter Two 23 Chapter Three 28 1. The Great Undefined Top There is one essential problem with mathematics as it stands: the fact that it is based entirely on the concept of division. That is, all of its formulae and theorems are founded on the idea of the number one, which is divided (has separation) from zero by some amount only knowable as itself, the number one. Repeated division produces 2, and 3, etc. There is a system of mathematical shorthand called “Typographical Number Theory”, from which it should theoretically be possible to write any conceivable mathematical formula or theorem, using only five basic axioms. These axioms are the basis of the current model of mathematics in its entirety. However, Kurt Gödel showed that it is possible to create any number of theorems using that system which could neither be proved to be true, nor ultimately denied, within the rules of the system;1 and this is done by positing a theorem in T.N.T. which reads: “Sentence G: This theorem is not a part of T.N.T.” The actual formulation of this theorem within the rules of T.N.T. is theoretically possible; and it has been taken as proof that all possible systems of logic are necessarily incomplete.2 There is an obvious point to be made here, which is that in every respect the “G-sentence” is equivalent in its unknowability to the number zero.