The Baphomet a Discourse Analysis of the Symbol in Three Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bible of the Adversary

THE BIBLE OF THE ADVERSARY MICHAEL W. FORD 1 THE BIBLE OF THE ADVERSARY MICHAEL W. FORD 2 Dedicated to ARASKH Who brought the wisdom of Ahriman to Humanity, who recognized “As Above, So Below” 3 THE BIBLE OF THE ADVERSARY By Michael W. Ford Copyright © 2007 by Michael W. Ford All rights reserved. No part of this book, in part or in whole, may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized, in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical articles, books and reviews. Illustrations by Various medieval sources and Gustave Dore. Sigils, Seals and Yatukih designs by Michael W. Ford Qlippothic Sigils illustrated by Michael W. Ford First edition 2007 Succubus Productions EBOOK EDITION 2009 Information: Succubus Productions PO Box 926344 Houston, TX 77292 USA Website: http://www.luciferianwitchcraft.com email: [email protected] 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction pg 6 The Adversarial Doctrine pg 8 THE BOOK OF ANDAR (fire) pg 9 Beginning Questions pg 10 The Precepts of Lucifer pg 13 Samaelian Diatribe pg 22 THE BOOK OF AKOMAN (Air) pg 27 Definitions of Magick pg 28 Luciferian Ideology pg 30 Luciferian Laws pg 40 Ahriman – Darkness embodied: Symbolism pg 52 Luciferian Religious Holidays pg 68 Liber Legion – Infernal Names pg 71 The Qlippoth – pg 96 Summoning Qlippothic Forces pg 112 Tiamat – the Primal Abyss pg 130 Drujo Demana – Book of Dead Names pg 134 THE BOOK OF TAROMAT (Earth) pg 145 Mastery of the Earth – Controlling your Destiny pg 146 Symbols and Meaning pg 160 Three Types of Luciferian Magick pg 174 Banishing Rituals and Preparation pg 176 THE BOOK OF ZAIRICH (Water) RITUAL MAGICK pg 186 Yatukih Sorcery – Way-i-vatar pg 187 Yatukih Ritual Steps pg 195 THE BOOK OF AZAL’UCEL (Spirit) pg 287 BIBLIOGRAPHY pg 316 GLOSSARY pg 317 5 INTRODUCTION To attempt to define a faith can be a difficult task. -

The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor Lavey

The Rites of Lucifer On the altar of the Devil up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity. The Satanic ritual cham- ber is die ideal setting for the entertainment of unspoken thoughts or a veritable palace of perversity. Now one of the Devil's most devoted disciples gives a detailed account of all the traditional Satanic rituals. Here are the actual texts of such forbidden rites as the Black Mass and Satanic Baptisms for both adults and children. The Satanic Rituals Anton Szandor LaVey The ultimate effect of shielding men from the effects of folly is to fill the world with fools. -Herbert Spencer - CONTENTS - INTRODUCTION 11 CONCERNING THE RITUALS 15 THE ORIGINAL PSYCHODRAMA-Le Messe Noir 31 L'AIR EPAIS-The Ceremony of the Stifling Air 54 THE SEVENTH SATANIC STATEMENT- Das Tierdrama 76 THE LAW OF THE TRAPEZOID-Die elektrischen Vorspiele 106 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTAIN-Homage to Tchort 131 PILGRIMS OF THE AGE OF FIRE- The Statement of Shaitan 151 THE METAPHYSICS OF LOVECRAFT- The Ceremony of the Nine Angles and The Call to Cthulhu 173 THE SATANIC BAPTISMS-Adult Rite and Children's Ceremony 203 THE UNKNOWN KNOWN 219 The Satanic Rituals INTRODUCTION The rituals contained herein represent a degree of candor not usually found in a magical curriculum. They all have one thing in common-homage to the elements truly representative of the other side. The Devil and his works have long assumed many forms. Until recently, to Catholics, Protestants were devils. To Protes- tants, Catholics were devils. -

The Illustration and the Meanings It Produces

The Illustration and the meanings it produces The loose chains, the satanic symbols, the ugly horned creature squatting on the pedestal, the nude couple with the woman sporting grapes (wine) on her tail and the man’s tail on fire: Rider Waite’s devil is the one of Christian culture. Note that this couple seems to be copied from Adam and Eve in Lovers (by the artwork). Devil, Lovers, and Two of Cups are three Rider Waite Tarot cards that show a couple with a figure above them interfering in their story. In each of these, the figure above is an interfering influence: a malefic (bad, adverse) influence in Devil and Two of Cups, and a (angry?) supervision in Lovers. Is that the angel that evicted them from the Garden? - because the terrain isn’t a garden. Nevertheless, it appears as a guardian angel at times. And in case you’re thinking Hierophant also has the three figures in its illustration: We are talking about a couple (not two male monks). Hierophant’s middle figure, the pope, isn’t interfering in the lives of the monks who also serve in the rituals. The reason I selected ‘bound’ to represent the title to call Devil in the back of your mind is that the chains, of course, are binding or are bonds; but also Devil is all about obligation, being bound to. That concept births most of the positive words for Devil. Yes, there are positive words for Devil! 1 The chains play varied roles in the concepts Devil lends itself to. -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival

Secret Traditions in the Modern Tarot: Folklore and the Occult Revival I first encountered the evocative images of the tarot, as no doubt many others have done, in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. This led to Pamela Coleman Smith’s tarot deck, and from there to the idiosyncratic writings of A.E. Waite with its musings on the Grail, on ‘secret doctrines’ and on the nature of mystical experience. Revival of interest in the tarot and the proliferation of tarot decks attests to the vibrancy of this phenomenon which appeared in the context of the eighteenth century occult revival. The subject is extensive, but my topic for now is the development of the tarot cards as a secret tradition legend in Britain from the late 1880’s to the 1930’s. (1) During this period, ideas about the nature of culture drawn from folklore and anthropological theory combined with ideas about the origins of Arthurian literature and with speculations about the occult nature of the tarot. These factors working together created an esoteric and pseudo-academic legend about the tarot as secret tradition. The most recent scholarly work indicates that tarot cards first appeared in Italy in the fifteenth century, while speculations about their occult meaning formed part of the French occult revival in the late eighteenth century. (Dummett 1980, 1996 ) The most authoritative historian of tarot cards, the philosopher Michael Dummett, is dismissive of occult and divinatory interpretations. Undoubtedly, as this excellent works points out, ideas about the antiquity of tarot cards are dependent on assumptions made at a later period, and there is a tendency among popular books to repeat each other rather than use primary sources. -

Metal Extremo: Estética “Pesada” No Black Metal

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS – ICH PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS LUANA CRISTINA SEIXAS METAL EXTREMO: ESTÉTICA “PESADA” NO BLACK METAL Juiz de Fora 2018 LUANA CRISTINA SEIXAS METAL EXTREMO: ESTÉTICA “PESADA” NO BLACK METAL ORIENTADORA: Elizabeth de Paula Pissolato Juiz de Fora 2018 LUANA CRISTINA SEIXAS METAL EXTREMO: ESTÉTICA “PESADA” NO BLACK METAL Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Ciências Sociais do Instituto de Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências Sociais. Orientadora: Prof.ª Drª. Elizabeth de Paula Pissolato Juiz de Fora 2018 Fiiha iatalográfia elaboraaa através ao "rograma ae geração automátia aa Biblioteia Universitária aa UFJF, iom os aaaos forneiiaos "elo(a) autor(a) SEIXAS, Luana Cristnaa Metal extremo: : estétia "esaaa no Blaik Metal / Luana Cristna SEIXASa -- 2018a 75 "a : ila Orientaaora: Elizabeth ae Paula Pissolato Dissertação (mestraao aiaaêmiio) - Universiaaae Feaeral ae Juiz ae Fora, Insttuto ae Ciêniias Humanasa Programa ae Pós Graauação em Ciêniias Soiiais, 2018a 1a Est1a Estétiaa 2a Blaik Metala 3a Juiz ae Foraa Ia Pissolato, Elizabeth ae Paula, orienta IIa Títuloa AGRADECIMENTOS Este trabalho apenas se tornou possível devido à contribuição e compreensão de várias pessoas. Agradeço aos meus pais, que no início da faculdade, quando nem compreendiam a minha área de atuação e me deram todo o apoio e que hoje explicam com orgulho o que sua filha estuda, até mesmo para os desconhecidos. Por me apresentar ao Rock quando ainda criança, e quando a situação se inverteu e eu apresentei o Metal, eles estavam abertos a conhecer. -

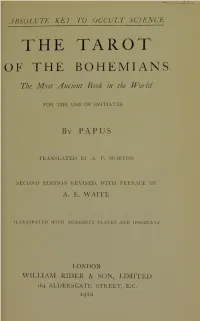

The Tarot of the Bohemians : the Most Ancient Book in the World

IBSOLUTE KET TO OCCULT SCIENCE THE TAROT ÜF THE BOHEMIANS The Most Ancient Book in the World FOR THE USE OF INITIATES By papus TRANSLATED BY A. P. MORTON SECOND EDITION REVISED, WITH PREFACE B Y A. E. WAITE ILLUSTRATED WITH N UMEROU S PLATES AND WOODCUTS LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LIMITED 164 ALDERSGATE STREET, E.C. 1910 Absolute Key to Oocult Science Frontispicce 2) BVÜ W Wellcome Libraty i forthe Histôry standing Il and ififcteï -, of Medi Printed by Ballantyne, HANSON &* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION An assumption of some kind being of common con- venience, that the line of least résistance may be pursued thereafter, I will open the présent considéra- tion by assuming that those who are quite unversed in the subject hâve referred to the pages which follow, and hâve thus become aware that the Tarot, on its external of that, side, is the probable progenitor playing-cards ; like these, it has been used for divination and for ail but that behind that is understood by fortune-telling ; this it is held to hâve a higher interest and another quality of importance. On a simple understanding, it is of allegory; it is of symbolism, on a higher plane; and, in fine, it is of se.cret doctrine very curiously veiled. The justification of these views is a different question; I am concerned wit>h ihe statement of fact are and this being said, I can that such views held ; pass to my real business, which" is in part critical and in part also explanatory, though not exactly on the elementary side. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Pronunciation of Samael

Pronunciation of Samael http://www.omnilexica.com/pronunciation/?q=Samael How is Samael hyphenated? British usage: Samael (no hyphenation) American usage: Sa -mael Sorry, no pronunciation of Samael yet. Content is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License ; ad- ditional terms may apply. See Copyright for details. Keyword Tool | Romanian-English Dictionary Privacy Policy 1 of 1 6/14/2014 9:16 PM Samael definition/meaning http://www.omnilexica.com/?q=Samael On this page: Group Miscellanea Printed encyclopedias and other books with definitions for SAMAEL Online dictionaries and encyclopedias with entries for SAMAEL Photos about SAMAEL Scrabble value of S A M A E L 1 1 3 1 1 1 Anagrams of SAMAEL Share this page Samael is a industrial black metal band formed in 1987 in Sion, Switzerland. also known as Samaël members: Xytras since 1987 Vorph since 1987 Christophe Mermod since 1992 Makro since 2002 Kaos between 1996 and 2002 (6 years) Rodolphe between 1993 and 1996 (3 years) Christophe Mermod since 1991 Pat Charvet between 1987 and 1988 genres: Black metal, Dark metal, Industrial metal, Heavy metal , Symphonic metal, European industrial metal, Grindcore , 1 of 7 6/14/2014 9:17 PM Samael definition/meaning http://www.omnilexica.com/?q=Samael Symphonic black metal albums: "Into the Infernal Storm of Evil", "Macabre Operetta", "From Dark to Black", "Medieval Prophecy", "Worship Him", "Blood Ritual", "After the Sepulture", "1987–1992", "Ceremony of Opposites", "Rebel- lion", "Passage", "Exodus", "Eternal", "Black Trip", "Telepath", "Reign of Light", "On Earth", "Lessons in Magic #1", "Ceremony of Opposites / Re- bellion", "Aeonics: An Anthology", "Solar Soul", "Above", "Antigod", "Lux Mundi", "A Decade in Hell" official website: www.samael.info Samael is an important archangel in Talmudic and post-Talmudic lore, a figure who is accuser, seducer and destroyer, and has been regarded as both good and evil. -

The Philosopher's Stone

The Philosopher’s Stone Dennis William Hauck, Ph.D., FRC Dennis William Hauck is the Project Curator of the new Alchemy Museum, to be built at Rosicrucian Park in San Jose, California. He is an author and alchemist working to facilitate personal and planetary transformation through the application of the ancient principles of alchemy. Frater Hauck has translated a number of important alchemy manuscripts dating back to the fourteenth century and has published dozens of books on the subject. He is the founder of the International Alchemy Conference (AlchemyConference.com), an instructor in alchemy (AlchemyStudy.com), and is president of the International Alchemy Guild (AlchemyGuild. org). His websites are AlchemyLab.com and DWHauck.com. Frater Hauck was a presenter at the “Hidden in Plain Sight” esoteric conference held at Rosicrucian Park. His paper based on that presentation entitled “Materia Prima: The Nature of the First Matter in the Esoteric and Scientific Traditions” can be found in Volume 8 of the Rose+Croix Journal - http://rosecroixjournal.org/issues/2011/articles/vol8_72_88_hauck.pdf. he Philosopher’s Stone was the base metal into incorruptible gold, it could key to success in alchemy and similarly transform humans from mortal Thad many uses. Not only could (corruptible) beings into immortal (incor- it instantly transmute any metal into ruptible) beings. gold, but it was the alkahest or universal However, it is important to remember solvent, which dissolved every substance that the Stone was not just a philosophical immersed in it and immediately extracted possibility or symbol to alchemists. Both its Quintessence or active essence. The Eastern and Western alchemists believed it Stone was also used in the preparation was a tangible physical object they could of the Grand Elixir and aurum potabile create in their laboratories. -

Goodbye Consett

GOODBYE CONSETT Excerpts from STORIES FROM A SONGWRITERS LIFE by Steve Thompson Cover image: Mark Mylchreest. Proof reading: Jim Harle (who still calls me Stevie). © 2020 Steve Thompson. All rights reserved. FOREWORD INTO THE UNKOWN By Trev Teasdel (Poet, author and historian) We almost thought of giving in Searching for that distant dream” Steve Thompson, Journey’s End. For a working-class man born in Consett, County Durham, UK apprenticed to the steel industry, with expectations only of the inevitable, Steve Thompson has managed to weld together, over 50 years, an amazing career as hit songwriter, musician, rock band leader, record producer, ideas man, raconteur, radio producer, community media mogul, workshop leader and much more. The world is full of unsung heroes, the people behind the scenes who pull the strings, spark ideas, write the material for others to sing and while Steve may be one of them, his songs at least have been well sung by some of the top artists in show business, and he’s worked alongside some of the top producers of the time. This is what this book is about – those songs that will be familiar to you even if you never knew who wrote them, the stories that lie behind them; the highs and lows, told with honesty, clarity and humour. There’s nothing highfalutin about Steve Thompson, he’s pulled himself up by his own bootstraps, achieved his dream, despite setbacks, and through it remains humble (if a little boastful – as you will see!), a staunchly people’s man with a wicked sense of humour (and I do mean wicked!). -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”.