Storm Spotting and Public Awareness Since the First Tornado Forecasts of 1948

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

23 Public Reaction to Impact Based Warnings During an Extreme Hail Event in Abilene, Texas

23 PUBLIC REACTION TO IMPACT BASED WARNINGS DURING AN EXTREME HAIL EVENT IN ABILENE, TEXAS Mike Johnson, Joel Dunn, Hector Guerrero and Dr. Steve Lyons NOAA, National Weather Service, San Angelo, TX Dr. Laura Myers University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL Dr. Vankita Brown NOAA/National Weather Service Headquarters, Silver Spring, MD 1. INTRODUCTION 3. HOW THE PUBLIC REACTED TO THE WARNINGS A powerful, supercell thunderstorm with hail up to the Of the 324 respondents, 86% were impacted by the size of softballs (>10 cm in diameter) and damaging extreme hail event. Listed below are highlighted winds impacted Abilene, Texas, during the Children's responses to some survey questions. Art and Literacy Festival and parade on June 12, 2014. It caused several minor injuries. This storm produced 3.1 Survey question # 3 widespread damage to vehicles, homes, and businesses, costing an estimated $400 million. More People rely on various sources of information when than 200 city vehicles sustained significant damage and making a decision to prepare for hazardous weather Abilene Fire Station #4 was rendered uninhabitable. events. Please indicate the sources that influenced your Giant hail of this magnitude is a rare phenomenon decisions on how to prepare BEFORE this severe (Blair, et al., 2011), but is responsible for a thunderstorm event occurred. disproportionate amount of damage. 1) Local television In support of a larger National Weather Service 2) Websites/social media (NWS) effort, the San Angelo Texas Weather Forecast 3) Wireless alerts/cell phones -

Tropical Cyclone Report for Hurricane Ivan

Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Ivan 2-24 September 2004 Stacy R. Stewart National Hurricane Center 16 December 2004 Updated 27 May 2005 to revise damage estimate Updated 11 August 2011 to revise damage estimate Ivan was a classical, long-lived Cape Verde hurricane that reached Category 5 strength three times on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale (SSHS). It was also the strongest hurricane on record that far south east of the Lesser Antilles. Ivan caused considerable damage and loss of life as it passed through the Caribbean Sea. a. Synoptic History Ivan developed from a large tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on 31 August. Although the wave was accompanied by a surface pressure system and an impressive upper-level outflow pattern, associated convection was limited and not well organized. However, by early on 1 September, convective banding began to develop around the low-level center and Dvorak satellite classifications were initiated later that day. Favorable upper-level outflow and low shear environment was conducive for the formation of vigorous deep convection to develop and persist near the center, and it is estimated that a tropical depression formed around 1800 UTC 2 September. Figure 1 depicts the “best track” of the tropical cyclone’s path. The wind and pressure histories are shown in Figs. 2a and 3a, respectively. Table 1 is a listing of the best track positions and intensities. Despite a relatively low latitude (9.7o N), development continued and it is estimated that the cyclone became Tropical Storm Ivan just 12 h later at 0600 UTC 3 September. -

Article a Climatological Perspective on the 2011 Alabama Tornado

Chaney, P. L., J. Herbert, and A. Curtis, 2013: A climatological perspective on the 2011 Alabama tornado outbreak. J. Operational Meteor., 1 (3), 1925, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15191/nwajom.2013.0103. Journal of Operational Meteorology Article A Climatological Perspective on the 2011 Alabama Tornado Outbreak PHILIP L. CHANEY Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama JONATHAN HERBERT and AMY CURTIS Jacksonville State University, Jacksonville, Alabama (Manuscript received 23 January 2012; in final form 17 September 2012) ABSTRACT This paper presents a comparison of the recent 27 April 2011 tornado outbreak with a tornado climatology for the state of Alabama. The climatology for Alabama is based on tornadoes that affected the state during the 19812010 period. A county-level risk index is produced from this climatology. Tornado tracks from the 2011 outbreak are mapped and compared with the climatology and risk index. There were 62 tornadoes in Alabama on 27 April 2011, including many long-track and intense tornadoes. The event resulted in 248 deaths in the state. The 2011 outbreak is also compared with the April 1974 tornado outbreak in Alabama. 1. Introduction population density (Gagan et al. 2010; Dixon et al. 2011). Tornadoes have been documented in every state in Alabama is affected in the spring and fall by the United States and on every continent except midlatitude cyclones, often associated with severe Antarctica. The United States has by far the most weather and tornadoes. During summer and fall tornado reports annually of any country, averaging tornadoes also can be produced by tropical cyclones. A about 1,300 yr-1. -

Samantha Santeiu 02-15-09 Sec. 9, Dave Defina Chasing a Storm

Samantha Santeiu 02-15-09 Sec. 9, Dave DeFina Chasing a Storm Specific Purpose Statement : To inform my audience how meteorologists chase storms and about the importance of storm chasing in meteorological research. Central Idea : Storm chasing requires special tools and software; chases follow a general procedure on the chase day; and chasing has great importance in meteorological research. Pattern of Organization : topical. INTRODUCTION It’s September, 1900, in Galveston, Texas. Isaac Cline, a well-known climatologist, rides his horse and buggy along the beach. He’s here to observe the unusually high, gusting winds and huge waves crashing onshore. He orders the people of Galveston to evacuate. [VISUAL AID] Little did he know, he had just chased the massive Galveston hurricane of 1900 that would proceed to kill at least 6,000 people in the area. According to “A Brief History of Storm Chasing” on the National Association of Storm Chasers and Spotters website, this is one of the first accounts of storm chasing that we have. How about this: how many of you have seen the movie Twister ? [VISUAL AID] The basic storyline is that two people are storm chasers, and in the end they chase an epically huge tornado in the name of research. That is a more modern, albeit a bit inaccurate, account of storm chasing. I would like to inform you today about chasing storms, the way meteorologists do it. I plan to research severe storms as a career, so I have investigated the topic thoroughly and interviewed peers and professors on the subject. While storm chasing may seem like fun, there’s actually a lot involved. -

Riding the Storm

physicsworld.com Careers Riding the storm out A career in severe-weather research offers flexibility and plenty of opportunities to experience the fascinating physics of the rotating fluid called the atmosphere. Josh Wurman describes the science of storm-chasing and why hurricanes are scarier than tornadoes Take me to the weather Josh Wurman enjoys the freedom that being a freelance meteorologist affords him. I am standing on a bridge near the North thematical, essentially applied fluid dynam- mapped out the winds inside tornadoes, so Carolina coast. There is a light breeze, and I ics, and the real-world effects of these equa- no-one really knew how strong they were. am enjoying some hazy sunshine. But this tions can be seen every day. The equations After reading the relevant literature, I de- calm is an illusion: in a few minutes winds of of motion for the atmosphere cause trees to cided that a more ambitious technological up to 45 m s–1 (100 mph) will sweep in again. be blown down, hail to fall and snowdrifts and logistical approach could push back the The approaches to my section of the bridge to pile up – all things that I could witness veil of ignorance about these fascinating phe- are already drowned under 2.5 m of water, while growing up in Pennsylvania. nomena. So in 1994 I decided to shift focus, and my companions on this island are an I started out as a physics major at the Mas- leaving NCAR for a faculty position at the eclectic mix of traumatized animals, inclu- sachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Oklahoma, where I developed ding snakes, rats, wounded pelicans and but my real interest was meteorology, in a prototype mobile weather radar system frogs. -

Skywarn Storm Spotter Guide

Skywarn Storm Spotter Guide ...For Western Nevada and Eastern California... National Weather Service Reno, Nevada CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................... 3 A Note to Amateur Radio Operators..................................................................... 4 Who to Call........................................................................................................... 5 NWS Reno County Warning Area Map ................................................................ 6 What to Report -Tornadoes / Severe Thunderstorms ......................................................... 7 -Heavy Rain/Flooding ................................................................................ 8 -Winter Storms......................................................................................... 10 -Fog/Other ............................................................................................... 11 Estimating Precipitation Intensity........................................................................ 12 Beaufort Wind Scale........................................................................................... 13 Handy Dandy Hail Size Estimator....................................................................... 14 After the Storm ................................................................................................... 15 Watch/Warning/Advisory Criteria........................................................................ 16 Sources -

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & a Brief Look at the 18

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & A Brief Look At The 18 June 2010 Derecho Gino Izzi National Weather Service, Chicago IL Outline • Meteorology 301: Squall lines – Brief review of thunderstorm basics – Squall lines – Squall line tornadoes – Mesovorticies • Storm spotting for squall lines • Brief Case Study of 18 June 2010 Event Thunderstorm Ingredients • Moisture – Gulf of Mexico most common source locally Thunderstorm Ingredients • Lifting Mechanism(s) – Fronts – Jet Streams – “other” boundaries – topography Thunderstorm Ingredients • Instability – Measure of potential for air to accelerate upward – CAPE: common variable used to quantify magnitude of instability < 1000: weak 1000-2000: moderate 2000-4000: strong 4000+: extreme Thunderstorms Thunderstorms • Moisture + Instability + Lift = Thunderstorms • What kind of thunderstorms? – Single Cell – Multicell/Squall Line – Supercells Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? – Short/simplistic answer: CAPE vs Shear Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? (Longer/more complex answer) – Lot we don’t know, other factors (besides CAPE/shear) include • Strength of forcing • Strength of CAP • Shear WRT to boundary • Other stuff Thunderstorm Types • Multi-cell squall lines most common type of severe thunderstorm type locally • Most common type of severe weather is damaging winds • Hail and brief tornadoes can occur with most the intense squall lines Squall Lines & Spotting Squall Line Terminology • Squall Line : a relatively narrow line of thunderstorms, often -

Workshop on Weather Ready Nation: Science Imperatives for Severe Thunderstorm Research, Held 24-26 April, 2012 in Birmingham AL

Workshop on Weather Ready Nation: Science Imperatives for Severe Thunderstorm Research, Held 24-26 April, 2012 in Birmingham AL Sponsored by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Science Foundation Final Report Edited by Michael K. Lindell, Texas A&M University and Harold Brooks, National Severe Storms Laboratory Hazard Reduction & Recovery Center Texas A&M University College station TX 77843-3137 17 September 2012 Executive Summary The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) workshop sponsored a workshop entitled Weather Ready Nation: Science Imperatives for Severe Thunderstorm Research on 24-26 April, 2012 in Birmingham Alabama. Prior to the workshop, teams of authors completed eight white papers, which were read by workshop participants before arriving at the conference venue. The workshop’s 63 participants—representing the disciplines of civil engineering, communication, economics, emergency management, geography, meteorology, psychology, public health, public policy, sociology, and urban planning—participated in three sets of discussion groups. In the first set of discussion groups, participants were assigned to groups by discipline and asked to identify any research issues related to tornado hazard response that had been overlooked by the 2011 Norman Workshop report (UCAR, 2012) or the white papers (see Appendix A). In the second set of discussion groups, participants were distributed among interdisciplinary groups and asked to revisit the questions addressed in the disciplinary groups, identify any interdependencies across disciplines, and recommend criteria for evaluating prospective projects. In the third set of discussion groups, participants returned to their initial disciplinary groups and were asked to identify and describe at least three specific research projects within the research areas defined by their white paper(s) and to assess these research projects in terms of the evaluation criteria identified in the interdisciplinary groups. -

The Birth and Early Years of the Storm Prediction Center

AUGUST 1999 CORFIDI 507 The Birth and Early Years of the Storm Prediction Center STEPHEN F. C ORFIDI NOAA/NWS/NCEP/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 12 August 1998, in ®nal form 15 January 1999) ABSTRACT An overview of the birth and development of the National Weather Service's Storm Prediction Center, formerly known as the National Severe Storms Forecast Center, is presented. While the center's immediate history dates to the middle of the twentieth century, the nation's ®rst centralized severe weather forecast effort actually appeared much earlier with the pioneering work of Army Signal Corps of®cer J. P. Finley in the 1870s. Little progress was made in the understanding or forecasting of severe convective weather after Finley until the nascent aviation industry fostered an interest in meteorology in the 1920s. Despite the increased attention, forecasts for tornadoes remained a rarity until Air Force forecasters E. J. Fawbush and R. C. Miller gained notoriety by correctly forecasting the second tornado to strike Tinker Air Force Base in one week on 25 March 1948. The success of this and later Fawbush and Miller efforts led the Weather Bureau (predecessor to the National Weather Service) to establish its own severe weather unit on a temporary basis in the Weather Bureau± Army±Navy (WBAN) Analysis Center Washington, D.C., in March 1952. The WBAN severe weather unit became a permanent, ®ve-man operation under the direction of K. M. Barnett on 21 May 1952. The group was responsible for the issuance of ``bulletins'' (watches) for tornadoes, high winds, and/or damaging hail; outlooks for severe convective weather were inaugurated in January 1953. -

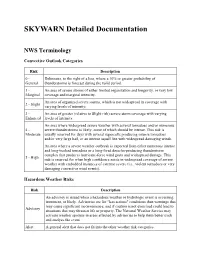

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation NWS Terminology Convective Outlook Categories Risk Description 0 - Delineates, to the right of a line, where a 10% or greater probability of General thunderstorms is forecast during the valid period. 1 - An area of severe storms of either limited organization and longevity, or very low Marginal coverage and marginal intensity. An area of organized severe storms, which is not widespread in coverage with 2 - Slight varying levels of intensity. 3 - An area of greater (relative to Slight risk) severe storm coverage with varying Enhanced levels of intensity. An area where widespread severe weather with several tornadoes and/or numerous 4 - severe thunderstorms is likely, some of which should be intense. This risk is Moderate usually reserved for days with several supercells producing intense tornadoes and/or very large hail, or an intense squall line with widespread damaging winds. An area where a severe weather outbreak is expected from either numerous intense and long-tracked tornadoes or a long-lived derecho-producing thunderstorm complex that produces hurricane-force wind gusts and widespread damage. This 5 - High risk is reserved for when high confidence exists in widespread coverage of severe weather with embedded instances of extreme severe (i.e., violent tornadoes or very damaging convective wind events). Hazardous Weather Risks Risk Description An advisory is issued when a hazardous weather or hydrologic event is occurring, imminent, or likely. Advisories are for "less serious" conditions than warnings that may cause significant inconvenience, and if caution is not exercised could lead to Advisory situations that may threaten life or property. The National Weather Service may activate weather spotters in areas affected by advisories to help them better track and analyze the event. -

Another Look at the 11 April 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak

Central Region Technical Attachment Number 15-02 December 2015 Another Look at the 11 April 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak JON CHAMBERLAIN National Weather Service, Rapid City, South Dakota ABSTRACT The 11 April 1965 tornado outbreak was one of the most devastating tornado outbreaks in recorded history, affecting six Midwestern states with significant loss of life and property. This storm system was particularly interesting for the number of discrete tornadic supercells in the southern Great Lakes, especially given the number of F3+ tornadoes. In addition, many supercells were observed to contain multiple funnels and multiple tornado cyclones (some occurring simultaneously). Dr. Theodore Fujita performed a comprehensive analysis of this event in the late 1960s, featuring a detailed analysis of both the meteorology and tornado damage paths. However, technology and science have progressed much between 1970 and 2015, with new forecast parameters and techniques available to forecasters. The Palm Sunday Outbreak of 1965 was re-examined using modern-day severe weather forecast parameters derived from observational data to help understand why this storm system produced such violent thunderstorms, particularly across extreme northern Indiana. In order to do this, approximately 200 handwritten surface observations were obtained from the National Climatic Data Center’s Electronic Digital Archive Data System web interface. Once these observations were put into a database, several surface weather maps, synthetic soundings, hodographs, and upper-level analyses were constructed. These data, along with archived upper-air data, were used to calculate several severe weather forecast parameters, which truly revealed the magnitude of the event. 1. Introduction The 11 April 1965 tornado outbreak was one of the most devastating tornado outbreaks in recorded history. -

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE of DUPAGE METEOROLOGY Focus on Anticipating and Spotting

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE OF DUPAGE METEOROLOGY HTTP://WEATHER.COD.EDU Focus on Anticipating and Spotting • What do you look for? • What will you actually see? • Can you identify what is going on with the storm? Is Gilbert married? Hmmmmm….rumor has it….. Its all about the updraft! Not that easy! • Various types of storms and storm structures. • A tornado is a “big sucky • Obscuration of important thing” and underneath the features make spotting updraft is where it forms. difficult. • So find the updraft! • The closer you are to a storm the more difficult it becomes to make these identifications. Conceptual models Reality is much harder. Basic Conceptual Model Sometimes its easy! North Central Illinois, 2-28-17 (Courtesy of Matt Piechota) Other times, not so much. Reality usually is far more complicated than our perfect pictures Rain Free Base Dusty Outflow More like reality SCUD Scattered Cumulus Under Deck Sigh...wall clouds! • Wall clouds help spotters identify where the updraft of a storm is • Wall clouds may or may not be present with tornadic storms • Wall clouds may be seen with any storm with an updraft • Wall clouds may or may not be rotating • Wall clouds may or may not result in tornadoes • Wall clouds should not be reported unless there is strong and easily observable rotation noted • When a clear slot is observed, a well written or transmitted report should say as much Characteristics of a Tornadic Wall Cloud • Surface-based inflow • Rapid vertical motion (scud-sucking) • Persistent • Persistent rotation Clear Slot • The key, however, is the development of a clear slot Prof.