Tropical Cyclone Report for Hurricane Ivan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skywarn Storm Spotter Guide

Skywarn Storm Spotter Guide ...For Western Nevada and Eastern California... National Weather Service Reno, Nevada CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................... 3 A Note to Amateur Radio Operators..................................................................... 4 Who to Call........................................................................................................... 5 NWS Reno County Warning Area Map ................................................................ 6 What to Report -Tornadoes / Severe Thunderstorms ......................................................... 7 -Heavy Rain/Flooding ................................................................................ 8 -Winter Storms......................................................................................... 10 -Fog/Other ............................................................................................... 11 Estimating Precipitation Intensity........................................................................ 12 Beaufort Wind Scale........................................................................................... 13 Handy Dandy Hail Size Estimator....................................................................... 14 After the Storm ................................................................................................... 15 Watch/Warning/Advisory Criteria........................................................................ 16 Sources -

10R.3 the Tornado Outbreak Across the North Florida Panhandle in Association with Hurricane Ivan

10R.3 The Tornado Outbreak across the North Florida Panhandle in association with Hurricane Ivan Andrew I. Watson* Michael A. Jamski T.J. Turnage NOAA/National Weather Service Tallahassee, Florida Joshua R.Bowen Meteorology Department Florida State University Tallahassee, Florida Jason C. Kelley WJHG-TV Panama City, Florida 1. INTRODUCTION their mobile homes were destroyed near Blountstown, Florida. Hurricane Ivan made landfall early on the morning of 16 September 2004, just west of Overall, there were 24 tornadoes reported Gulf Shores, Alabama as a category 3 across the National Weather Service (NWS) hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Tallahassee forecast area. The office issued Scale. Approximately 117 tornadoes were 130 tornado warnings from the afternoon of 15 reported associated with Ivan across the September until just after daybreak on 16 southeast United States. Eight people were September. killed and 17 were injured by tornadoes (Storm Data 2004; Stewart 2004). The most The paper examines the convective cells significant tornadoes occurred as hurricane within the rain bands of hurricane Ivan, which Ivan approached the Florida Gulf coast on the produced these tornadoes across the Florida afternoon and evening of 15 September. Panhandle, Big Bend, and southwest Georgia. The structure of the tornadic and non-tornadic The intense outer rain bands of Ivan supercells is examined for clues on how to produced numerous supercells over portions better warn for these types of storms. This of the Florida Panhandle, Big Bend, southwest study will focus on the short-term predictability Georgia, and Gulf coastal waters. In turn, of these dangerous storms, and will these supercells spawned dozens of investigate the problem of how to reduce the tornadoes. -

The Critical Role of Cloud–Infrared Radiation Feedback in Tropical Cyclone Development

The critical role of cloud–infrared radiation feedback in tropical cyclone development James H. Ruppert Jra,b,1, Allison A. Wingc, Xiaodong Tangd, and Erika L. Durane aDepartment of Meteorology and Atmospheric Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; bCenter for Advanced Data Assimilation and Predictability Techniques, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; cDepartment of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306; dKey Laboratory of Mesoscale Severe Weather, Ministry of Education, and School of Atmospheric Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China; and eEarth System Science Center, University of Alabama in Huntsville/NASA Short-term Prediction Research and Transition (SPoRT) Center, Huntsville, AL 35805 Edited by Kerry A. Emanuel, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and approved September 21, 2020 (received for review June 29, 2020) The tall clouds that comprise tropical storms, hurricanes, and within an incipient storm locally increase the atmospheric trapping typhoons—or more generally, tropical cyclones (TCs)—are highly of infrared radiation, in turn locally warming the lower–middle effective at trapping the infrared radiation welling up from the sur- troposphere relative to the storm’s surroundings (35–39). This face. This cloud–infrared radiation feedback, referred to as the mechanism is a positive feedback to the incipient storm, as it “cloud greenhouse effect,” locally warms the lower–middle tropo- promotes its thermally direct transverse circulation (38, 39) sphere relative to a TC’s surroundings through all stages of its life (Fig. 1A). Herein, we examine the role of this feedback in the cycle. Here, we show that this effect is essential to promoting and context of TC development in nature. -

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & a Brief Look at the 18

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & A Brief Look At The 18 June 2010 Derecho Gino Izzi National Weather Service, Chicago IL Outline • Meteorology 301: Squall lines – Brief review of thunderstorm basics – Squall lines – Squall line tornadoes – Mesovorticies • Storm spotting for squall lines • Brief Case Study of 18 June 2010 Event Thunderstorm Ingredients • Moisture – Gulf of Mexico most common source locally Thunderstorm Ingredients • Lifting Mechanism(s) – Fronts – Jet Streams – “other” boundaries – topography Thunderstorm Ingredients • Instability – Measure of potential for air to accelerate upward – CAPE: common variable used to quantify magnitude of instability < 1000: weak 1000-2000: moderate 2000-4000: strong 4000+: extreme Thunderstorms Thunderstorms • Moisture + Instability + Lift = Thunderstorms • What kind of thunderstorms? – Single Cell – Multicell/Squall Line – Supercells Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? – Short/simplistic answer: CAPE vs Shear Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? (Longer/more complex answer) – Lot we don’t know, other factors (besides CAPE/shear) include • Strength of forcing • Strength of CAP • Shear WRT to boundary • Other stuff Thunderstorm Types • Multi-cell squall lines most common type of severe thunderstorm type locally • Most common type of severe weather is damaging winds • Hail and brief tornadoes can occur with most the intense squall lines Squall Lines & Spotting Squall Line Terminology • Squall Line : a relatively narrow line of thunderstorms, often -

ISAIAS (AL092020) 30 July–4 August 2020

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE ISAIAS (AL092020) 30 July–4 August 2020 Andy Latto, Andrew Hagen, and Robbie Berg National Hurricane Center 1 11 June 2021 GOES-16 10.3-µM INFRARED SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE ISAIAS AT 0310 UTC 04 AUGUST 2020 AS IT MADE LANDFALL NEAR OCEAN ISLE BEACH, NORTH CAROLINA. Isaias was a hurricane that formed in the eastern Caribbean Sea. The storm affected the Leeward Islands, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Cuba, the Bahamas, and a large portion of the eastern United States. 1 Original report date 30 March 2021. Second version on 15 April updated Figure 12. This version corrects a wind gust value in the Winds and Pressures section and the track length of a tornado in Delaware. Hurricane Isaias 2 Table of Contents SYNOPTIC HISTORY .......................................................................................... 3 METEOROLOGICAL STATISTICS ...................................................................... 5 Winds and Pressure ........................................................................................... 5 Caribbean Islands and Bahamas ..................................................................... 6 United States ................................................................................................... 6 Rainfall and Flooding ......................................................................................... 7 Storm Surge ....................................................................................................... 8 Tornadoes ....................................................................................................... -

Background Hurricane Katrina

PARTPART 33 IMPACTIMPACT OFOF HURRICANESHURRICANES ONON NEWNEW ORLEANSORLEANS ANDAND THETHE GULFGULF COASTCOAST 19001900--19981998 HURRICANEHURRICANE--CAUSEDCAUSED FLOODINGFLOODING OFOF NEWNEW ORLEANSORLEANS •• SinceSince 1559,1559, 172172 hurricaneshurricanes havehave struckstruck southernsouthern LouisianaLouisiana ((ShallatShallat,, 2000).2000). •• OfOf these,these, 3838 havehave causedcaused floodingflooding inin NewNew thethe OrleansOrleans area,area, usuallyusually viavia LakeLake PonchartrainPonchartrain.. •• SomeSome ofof thethe moremore notablenotable eventsevents havehave included:included: SomeSome ofof thethe moremore notablenotable eventsevents havehave included:included: 1812,1812, 1831,1831, 1860,1860, 1915,1915, 1947,1947, 1965,1965, 1969,1969, andand 20052005.. IsaacIsaac MonroeMonroe ClineCline USWS meteorologist Isaac Monroe Cline pioneered the study of tropical cyclones and hurricanes in the early 20th Century, by recording barometric pressures, storm surges, and wind velocities. •• Cline charted barometric gradients (right) and tracked the eyes of hurricanes as they approached landfall. This shows the event of Sept 29, 1915 hitting the New Orleans area. • Storm or tidal surges are caused by lifting of the oceanic surface by abnormal low atmospheric pressure beneath the eye of a hurricane. The faster the winds, the lower the pressure; and the greater the storm surge. At its peak, Hurricane Katrina caused a surge 53 feet high under its eye as it approached the Louisiana coast, triggering a storm surge advisory of 18 to 28 feet in New Orleans (image from USA Today). StormStorm SurgeSurge •• The surge effect is minimal in the open ocean, because the water falls back on itself •• As the storm makes landfall, water is lifted onto the continent, locally elevating the sea level, much like a tsunami, but with much higher winds Images from USA Today •• Cline showed that it was then northeast quadrant of a cyclonic event that produced the greatest storm surge, in accordance with the drop in barometric pressure. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

HURRICANE TEDDY (AL202020) 12–23 September 2020

r d NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE TEDDY (AL202020) 12–23 September 2020 Eric S. Blake National Hurricane Center 28 April 2021 NASA TERRA MODIS VISIBLE SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE TEDDY AT 1520 UTC 22 SEPTEMBER 2020. Teddy was a classic, long-lived Cape Verde category 4 hurricane on the Saffir- Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. It passed northeast of the Leeward Islands and became extremely large over the central Atlantic, eventually making landfall in Nova Scotia as a 55-kt extratropical cyclone. There were 3 direct deaths in the United States due to rip currents. Hurricane Teddy 2 Hurricane Teddy 12–23 SEPTEMBER 2020 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Teddy originated from a strong tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on 10 September, accompanied by a large area of deep convection. The wave was experiencing moderate northeasterly shear, but a broad area of low pressure and banding features still formed on 11 September a few hundred n mi southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. Convection decreased late that day, as typically happens in the evening diurnal minimum period, but increased early on 12 September. This convection led to the development of a well-defined surface center, confirmed by scatterometer data, and the formation of a tropical depression near 0600 UTC 12 September about 500 n mi southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. The “best track” chart of the tropical cyclone’s path is given in Fig. 1, with the wind and pressure histories shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The best track positions and intensities are listed in Table 1.1 After the depression formed, further development was slow during the next couple of days due to a combination of northeasterly shear, dry air in the mid-levels and the large size and radius of maximum winds of the system. -

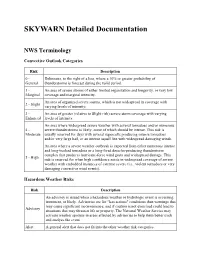

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation NWS Terminology Convective Outlook Categories Risk Description 0 - Delineates, to the right of a line, where a 10% or greater probability of General thunderstorms is forecast during the valid period. 1 - An area of severe storms of either limited organization and longevity, or very low Marginal coverage and marginal intensity. An area of organized severe storms, which is not widespread in coverage with 2 - Slight varying levels of intensity. 3 - An area of greater (relative to Slight risk) severe storm coverage with varying Enhanced levels of intensity. An area where widespread severe weather with several tornadoes and/or numerous 4 - severe thunderstorms is likely, some of which should be intense. This risk is Moderate usually reserved for days with several supercells producing intense tornadoes and/or very large hail, or an intense squall line with widespread damaging winds. An area where a severe weather outbreak is expected from either numerous intense and long-tracked tornadoes or a long-lived derecho-producing thunderstorm complex that produces hurricane-force wind gusts and widespread damage. This 5 - High risk is reserved for when high confidence exists in widespread coverage of severe weather with embedded instances of extreme severe (i.e., violent tornadoes or very damaging convective wind events). Hazardous Weather Risks Risk Description An advisory is issued when a hazardous weather or hydrologic event is occurring, imminent, or likely. Advisories are for "less serious" conditions than warnings that may cause significant inconvenience, and if caution is not exercised could lead to Advisory situations that may threaten life or property. The National Weather Service may activate weather spotters in areas affected by advisories to help them better track and analyze the event. -

Hurricane Eyewall Slope As Determined from Airborne Radar Reflectivity Data: Composites and Case Studies

368 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 28 Hurricane Eyewall Slope as Determined from Airborne Radar Reflectivity Data: Composites and Case Studies ANDREW T. HAZELTON AND ROBERT E. HART Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida (Manuscript received 19 April 2012, in final form 6 December 2012) ABSTRACT Understanding and predicting the evolution of the tropical cyclone (TC) inner core continues to be a major research focus in tropical meteorology. Eyewall slope and its relationship to intensity and intensity change is one example that has been insufficiently studied. Accordingly, in this study, radar reflectivity data are used to quantify and analyze the azimuthal average and variance of eyewall slopes from 124 flight legs among 15 Atlantic TCs from 2004 to 2011. The slopes from each flight leg are averaged into 6-h increments around the best-track times to allow for a comparison of slope and best-track intensity. A statistically significant re- lationship is found between both the azimuthal mean slope and pressure and between slope and wind. In addition, several individual TCs show higher correlation between slope and intensity, and TCs with both relatively high and low correlations are examined in case studies. In addition, a correlation is found between slope and radar-based eye size at 2 km, but size shows little correlation with intensity. There is also a tendency for the eyewall to tilt downshear by an average of approximately 108. In addition, the upper eyewall slopes more sharply than the lower eyewall in about three-quarters of the cases. Analysis of case studies discusses the potential effects on eyewall slope of both inner-core and environmental processes, such as vertical shear, ocean heat content, and eyewall replacement cycles. -

Comparison of Destructive Wind Forces of Hurricane Irma with Other Hurricanes Impacting NASA Kennedy Space Center, 2004-2017

Comparison of Destructive Wind Forces of Hurricane Irma with Other Hurricanes Impacting NASA Kennedy Space Center, 2004 - 2017 Presenter: Mrs. Kathy Rice Authors KSC Weather: Dr. Lisa Huddleston Ms. Launa Maier Dr. Kristin Smith Mrs. Kathy Rice NWS Melbourne: Mr. David Sharp NOT EXPORT CONTROLLED This document has been reviewed by the KSC Export Control Office and it has been determined that it does not meet the criteria for control under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) or Export Administration Regulations (EAR). Reference EDR Log #: 4657, NASA KSC Export Control Office, (321) 867-9209 1 Hurricanes Impacting KSC • In September 2017, Hurricane Irma produced sustained hurricane force winds resulting in facility damage at Kennedy Space Center (KSC). • In 2004, 2005, and 2016, hurricanes Charley, Frances, Jeanne, Wilma, and Matthew also caused damage at KSC. • Destructive energies from sustained wind speed were calculated to compare these hurricanes. • Emphasis is placed on persistent horizontal wind force rather than convective pulses. • Result: Although Hurricane Matthew (2016) provided the highest observed wind speed and greatest kinetic energy, the destructive force was greater from Hurricane Irma. 2 Powell & Reinhold’s Article 2007 • Purpose: “Broaden the scientific debate on how best to describe a hurricane’s destructive potential” • Names the following as poor indicators of a hurricane’s destructive potential • Intensity (Max Sustained Surface Winds): Provides a measure to compare storms, but does not measure destructive potential since it does not account for storm size. • The Saffir-Simpson scale: Useful for communicating risk to individuals and communities, but is only a measure of max sustained winds, again, not accounting for storm size. -

Hurricane Ivan Damage Survey

P 7.4 HURRICANE IVAN DAMAGE SURVEY Timothy P. Marshall* Haag Engineering Co. Dallas, Texas 1. INTRODUCTION The author conducted aerial and ground damage surveys along the Florida and Alabama coasts after Hurricane Ivan. The purpose of these surveys was to: 1) determine the height of the storm surge, 2) acquire wind velocity data, 3) determine the timing of each, and 4) assess the performance of buildings exposed to wind and water effects. Particular emphasis was placed on delineating wind and water damage. A similar study has just been published by FEMA (2005). The author rode out Hurricane Ivan near Pensacola, FL then conducted hundreds of site specific inspections the year following the hurricane. Most buildings examined were wood-framed structures. Remaining buildings consisted of concrete masonry as well as Figure 1. Enhanced color infrared satellite image of multi-story, steel-reinforced, concrete structures. Hurricane Ivan at landfall near Gulf Shores, AL around Various building failure modes were observed. 0700 UTC (2a.m.) on the morning of 16 September Typically, wind exploited poorly anchored or attached 2004. Arrow indicates location of author. Image roofs and vinyl siding whereas wave action courtesy of NOAA/NWS. undermined, collapsed and destroyed buildings near the coast. Wind damage generally began at roof levels Analysis of radar data revealed that Hurricane Ivan whereas wave damage attacked the bases of buildings. had a closed eyewall until it was about 100 km (62 Both lateral and uplift forces were applied to the miles) from the Alabama coast. According to Stewart buildings from wind and water and examples of such (2005), a combination of dry air from Louisiana, failures will be shown in this paper.