Strengthening the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act. Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Multi-Functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces

MULTI-FUNCTIONALITY OF THE IFUGAO RICE TERRACES Rogelio N. Concepcion Project Leader Director, Bureau of Soils and Water Management Multi-functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces Phase 1. Country paper for the ASEAN- Japan Multi-Functionality of Paddy Farming and its Impacts in ASEAN Countries Multi-functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces Participating Countries Brunei, Cambodia, Lao-PDR, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines Duration Phase 1: April 2001 – November 2003 Phase II: December 2003 – March 2006 Funding Source – MAF, Japan Multi-functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces Project Phase 1 Objectives 1. To establish common understanding on the importance of multi-functionality through analytical work in ASEAN member countries 2. To create appreciation on the contribution on multi-functionality to the ASEAN countries long term policy making for further development of sustainable agriculture in the rural areas. Operational Framework of Multi-functionality Groentfledt, 2003 Multi-functionality concept was first articulated in the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio De Janeiro in the context of discussion of contribution of agriculture to environmentally Sustainable Development. Matsumoto, 2002 Agricultural activities not only produce tangible products in the form of food and fiber, but also create non-tangible values, which are referred as the multi-functionality of agriculture. Multi-functionality is not tradable and cannot be reflected in the food prices. The tradable or marketable products of farming provide direct -

Proceedingsof the 2Nd Palawan Research Symposium 2015 I

Proceedingsof the 2nd Palawan Research Symposium 2015 i Science, Technology and Innovation for Sustainable Development nd Proceedings of the 2 Palawan Research Symposium 2015 National Research Forum on Palawan Sustainable Development 9-10 December 2015 Puerto Princesa City, Philippines Short extracts from this publication may be reproduced for individual use, even without permission, provided that this source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes is however prohibited without the written consent of the publisher. Electronic copy is also available in www.pcsd.gov.ph and www.pkp.pcsd.gov.ph. Editorial Board: Director Josephine S. Matulac, Planning Director, PCSDS Engr. Madrono P.Cabrestante Jr, Knowledge Management Division Head, PCSDS Prof. Mildred P. Palon, Research Director, HTU Dr. Patrick A. Regoniel, Research Director, PSU Dr. Benjamin J. Gonzales, Vice President for Research, Development & Extension, WPU Exec. Dir. Nelson P. Devanadera, Executive Director, PCSDS Editorial Staff: Celso Quiling Bernard F. Mendoza Lyn S. Valdez Jenevieve P. Hara Published by: Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff-ECAN Knowledge Management PCSD Building, Sports Complex Road, Brgy. Sta. Monica,Puerto Princesa City Palawan, Philippines Tel. No. +63 48 434-4235, Telefax: +63 48 434-4234 www.pkp.pcsd.gov.ph Philippine Copyright ©2016 by PCSDS Palawan, Philippines ISBN: ___________ Suggested Citation: Matulac, J.L.S, M.P. Cabrestante, M.P. Palon, P.A. Regoniel, B.J. Gonzales, and N.P. Devanadera. Eds. 2016. Proceedings of the 2nd Palawan Research Symposium 2015. National Research Forum on Palawan Sustainable Development, “Science, Technology & Innovation. Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines. Proceedingsof the 2nd Palawan Research Symposium 2015 ii Acknowledgement The PCSDS and the symposium-workshop collaborators would like to acknowledge the following: For serving as secretariat, documenters, and facilitating the symposium, concurrent sessions and workshops: Prof. -

3.5.4.2 Final Report of Kankana-Ey Besao Size

Ethnomedical documentation of selected Philippine ethnolinguistic groups: the Busaos Kankana-ey people of Barangay Catengan, Besao, Mountain Province A collaborative project of Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care, Department of Health, Sta Cruz, Manila University of the Philippines Manila, Ermita, Manila 2000 August Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We wish to thank the Provincial Health Office of Mountain Province for the assistance and suggestions given during the initial phase of the study, and Dr Penelope Domogo for the suggestions and referrals on the study sites. We also thank the people of Besao especially Hon Johnson N Bantog for the permission to conduct the study in his locality, and Ms Joyce Callisen for the guidance and help in the coordination in the study site. And lastly, we would like to give our deepest thanks to the people of Brgy Catengan, Brgy Captain Dondie Babake for allowing us to conduct our study in their community, the family of Mrs Vergie Sagampod for the warm acceptance and accommodation given the researcher during the study period, and the healers, mothers, youth members and children for the information that they shared. Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary Background of the study Objectives Methodology Review of literature Results Recommendations References Appendices Page 3 Ethnomedical documentation of selected Philippine ethnolinguistic groups: the Busaos Kankana-ey people of Besao, Mountain Province EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An ethnomedical documentation of the Busaos people in Mountain Province was conducted in March to July 2000. The five-month study focused on the indigenous healers present in the community. The study included the documentation of the health perceptions, beliefs and practices of the Busaos, including the ethnopharmacological knowledge of the community. -

Lo Fil) 2Ozo by and Between

* Contract ID 20Proo41 Contract Name Convergence and Specia! Support Program - Construction/ Improvement of Access Roads leading to Declared Tourism Destinations, Tadian-sagada Via Besao Road leading to Tirad Pass View, Fidelisan Falls, Sumaguing Cave, Balangagan Cave, Ayyuweng di lambak ed Tadian Festival, Kiltepan Sunrise, Besao Sunset Hanging Coffins, Echo Valley, Tadian, Mountain Province Location of the .Tadian, Mountain Province Contract CONTRACT AGREEMENT KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS: This CONTRACT AGREEMENT, made this lo fil) 2ozo by and between: The GOVERNMENT irr THE REPUBLTC OF THE PHILTPPTNES through the Department of Public Works and Highways-Mountain Province First District Engineering Office (DPWH-MPFDEO) represented herein by ALEXANDER C. CASTAfrEDA, District Engineer, duly authorized for this purpose, with main office address at Lower Caluttit, Bontoc, Mountain Province, hereinafter referred to as the "PROCURING ENTITY"; GENERAL CONSTRUCTION, a single proprietorship organized and existing and by virtue of laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with main office address at POBLACION, TADIAN, MOUNTAIN PROVINCE, represented herein by REYNALDO S. DEL AMOR, duly authorized for this purpose, hereinafter referred to as the *CONTRACTOR; WITNESSETH: WHEREAS, the PROCURING ENTITY is desirous that the CONTRACTOR execute the Works under 20PI0041 - Convergence and Special Support Program Construction/ Improvement of Access Roads leading to Declared Tourism Destinations, Tadian-Sagada via Besao Road leading to Tirad Pass View, 6 -

2278-6236 Inayan: the Tenet for Peace Among Igorots

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 INAYAN: THE TENET FOR PEACE AMONG IGOROTS Rhonda Vail G. Leyaley* Abstract: This research study was conducted to determine the meaning of Inayan and how this principle is used by the Igorots as a peaceful means of solving issues that involves untoward killings, accidents, theft and land grabbing. The descriptive method was used in this study. Key informants were interviewed using a prepared questionnaire. Foremost, the meaning of Inayan among Igorots is, it is the summary of the Ten Commandments. For more peaceful means, they’d rather do the rituals like the “Daw-es” to appease their pain and anger. This is letting the Supreme Being which they call Kabunyan take the course of action in “punishing” those who have committed wrong towards them. It is recommended that the principles of Inayan be disseminated to the younger generation through the curriculum; that the practices and rituals will be fully documented to be used as references; and to develop instructional materials that will advocate the principle of Inayan; Keywords: Inayan, Peace, Igorots, Rituals, Kankanaey *Bulanao, Tabuk City, Kalinga Vol. 5 | No. 2 | February 2016 www.garph.co.uk IJARMSS | 239 International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 I. INTRODUCTION In a society where tribal conflicts are very evident, a group of individuals has a very distinguishable practice in maintaining the culture of peace among themselves. They are the Igorots. The Cordillera region of Northern Philippines is the ancestral domain of the Igorots. -

ASIA-PACIFIC APRIL 2010 VOLUME 59 Focus Asia-Pacific Newsletter of the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center (HURIGHTS OSAKA) December 2010 Vol

FOCUS ASIA-PACIFIC APRIL 2010 VOLUME 59 Focus Asia-Pacific Newsletter of the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center (HURIGHTS OSAKA) December 2010 Vol. 62 Contents Editorial Indigenous Peoples of Thailand This is a short introduction of the indigenous peoples of Thailand and a discussion of their problems. - Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand Being Indigenous Page 2 Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines: Continuing Struggle Land is an important part of the survival of the indigenous This is a discussion on the causes of marginalization of the indigenous peoples peoples, be it in Asia, Pacific or elsewhere. Land is not simply in the Philippines, including the role of land necessary for physical existence but for the spiritual, social, laws in facilitating dispossession of land. - Rey Ty and cultural survival of indigenous peoples and the Page 6 continuation of their historical memory. Marriage Brokerage and Human Rights Issues Marginalization, displacement and other forms of oppression This is a presentation on the continuing are experienced by indigenous peoples. Laws and entry of non-Japanese women into Japan with the help of the unregulated marriage development programs displace indigenous peoples from brokerage industry. Suspicion arises on their land. Many indigenous peoples have died because of the industry’s role in human trafficking. - Nobuki Fujimoto them. Discriminatory national security measures as well as Page 10 unwise environmental programs equally displace them. Human Rights Events in the Asia-Pacific Page 14 Modernization lures many young members of indigenous communities to change their indigenous existence; while Announcement traditional wisdom, skills and systems slowly lose their role as English Website Renewed the elders of the indigenous communities quietly die. -

Pagdiwata Festival

Pagdiwata Festival Date: December 8 Location: Puerto Princesa, Palawan Celebrated by the Tagbanua people of Palawan, the Pagdiwata Ritual Festival is an annual event of acknowledgement and expression of Palawan people to the deities same time seeking for the deitiesí help in healing the sick and in need and offer prayers for departed loved ones. People who are in serious health conditions also come to join the event, treated by their family being the medium of healing. The town proper of Aborlan in Palawan is host to the Pagdiwata Tribal Ritual held every month of December on a full moon. Aborlan is a small municipality that has the mountains and the Sulu Sea surrounding it. It has about 19 barangays and a population of no more than 30,000 people. To get to Aborlan to see the Pagdiwata Tribal Ritual which is about 75 kilometers away from Puerto Princesa, one can either hop on a bus or ride a jeepney which departs from the capital city daily. The ride should be about 2 hours. If one is booked at a hotel in Aborlan, transportation becomes much easier because the hotel picks up its guests upon their arrival at the Puerto Princesa Airport. The celebration of Pagdiwata is also an opportunity to celebrate bountiful harvest or succesful hunting trip. The Babaylan, or the high priest, lead the ritual, since he is considered the most powerful and influential among the people of Tagbanua. They strongly believe that disrespecting the Babaylan faces severe punishment by the supernaturals. The festivity includes offering of wine, nuts, wax, food, and many others. -

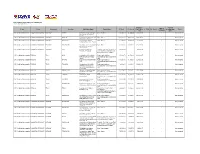

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

Tagbanwa Grammar.Vp Tuesday, December 08, 2009 2:45:26 PM Color Profile: Generic CMYK Printer Profile Composite Default Screen

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen Linguistic Society of the Philippines Special Monograph Issue, Number 48 The Philippine Journal of Linguistics (PJL) is the official publication of the Linguistic Society of the Philippines. It publishes studies in descriptive, comparative, historical, and areal linguistics. Although its primary interest is in linguistic theory, it also publishes papers on the application of theory to language teaching, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, anthropological principles, etc. Such papers should, however, be chiefly concerned with the principles which underlie specific techniques rather than with the mechanical aspects of such techniques. Articles are published in English, although papers written in Filipino, an official language of the Philippines, will occasionally appear. Since the Linguistic Society of the Philippines is composed of members whose paramount interests are the Philippine languages, papers on these and related languages are given priority in publication. This does not mean, however, that the journal will limit its scope to the Austronesian language family. Studies on any aspect of language structure are welcome. The Special Monograph Series publishes longer studies in the same areas of interest as the PJL, or collections of articles on a single theme. Manuscripts for publication, exchange journals, and books for review or listing should be sent to the Editor, Ma. Lourdes S. Bautista, De La Salle University, 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines. Manuscripts from the United States and Europe should be sent to Dr. Lawrence A. Reid, Pacific and Asia Linguistics Institute, University of Hawaii, 1890 East-West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, U.S.A. Editorial Board Editor: Ma. Lourdes S. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

The Lumad Equation 6

KêtindêgISSN 2345-8461 Volume 3 Issue 2 * January, 2015 *56pages An official publication of the IPDEV Project, Empowering Indigenous Peoples in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao WHAT’S INSIDE? 3 - The Lumad equation 6 - Soldiers plant trees for IPs 8 - 2014 State of the IP Address 11 - Does the BBL offer more than the IPRA? 14 - Celebration, Solidarity & Hope 17 - Group eyes IPs’ peace agenda 18 - Already hurt and confused 20 - Awards for awesome wards 26 - Reliving and enriching Sulagad 28 - A return to those old ideal ways 30 - Festival in the truest sense 32 - Who are protecting the IP children and youth in the ARMM? 38 - Mining equates to IPs’ extinction 43 - “Don’t leave us” 44 - Prayer and ritual on World IP Day 50 - 10th Project Sounding Board 51 - Salamat po! Development Consultants Inc. D E V C O N THIS PROJECT IS SUPPORTED Recognition of the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao for BY THE EUROPEAN UNION Empowerment and Sustainable Development (IPDEV) is a project implemented by the consortium: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung e.V., Institute for Autonomy and Governance (IAG) and DEVCON Development Consultants Inc. Kêtindêg, in Teduray roughly means standing up for something, making one be seen and be felt among the many. The word is not far from the Cebuano, Tagalog or Maguindanao variations of tindog, tindig and tindeg respectively. It is a fitting title for a The Lumad regular publication that attempts to capture the experiences gathered in this journey of recognizing the rights of the Lumad in the ARMM.