Human Rights Situation in Closed Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae, Tersilochinae)

Труды Русского энтомологического общества. С.-Петербург, 2004. Т. 75 (1): 46–63. Proceedings of the Russian Entomological Society. St. Petersburg, 2004. Vol. 75 (1): 46–63. A review of the Palaearctic species of the genera Barycnemis Först., Epistathmus Först. and Spinolochus Horstm. (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae, Tersilochinae) A.I. Khalaim Обзор палеарктических видов родов Barycnemis Först., Epistathmus Först. and Spinolochus Horstm. (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae, Tersilochinae) А.И. Халаим Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. Petersburg 199034, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Six new species of the genus Barycnemis are described: B. asiatica sp. n. (Eastern Kazakhstan, Russian Altai and Mongolia), B. suspecta sp. n. (Georgia), B. tarsator sp. n. (Kyrghyzstan), B. terminator sp. n. (Kyrghyzstan), B. tibetica sp. n. (Tibet) and B. tobiasi sp. n. (Buryatia and south of the Russian Far East). New data on distribution of the Palaearctic species of the genera Barycnemis Först., Epistathmus Först. and Spinolochus Horstm. are provided. A key to the Palaearctic species of the genus Barycnemis is given. Key words. Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Tersilochinae, Barycnemis, Epistathmus, Spinolochus, taxon- omy, new species, Palaearctic. Резюме. Описано шесть новых видов: Barycnemis asiatica sp. n. (Восточный Казахстан, Россий- ский Алтай и Монголия), B. suspecta sp. n. (Грузия), B. tarsator sp. n. (Киргизия), B. terminator sp. n. (Киргизия), B. tibetica sp. n. (Тибет) и B. tobiasi sp. n. (Бурятия и юг Дальнего Востока России). Представлены новые данные о распространении видов родов Barycnemis Först., Epistathmus Först. и Spinolochus Horstm. в Палеарктике. Дана определительная таблица палеарктических видов рода Barycnemis. Ключевые слова. Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Tersilochinae, Barycnemis, Epistathmus, Spinolo- chus, систематика, новые виды, Палеарктика. -

Economic Prosperity Initiative

USAID/GEORGIA DO2: Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth October 1, 2011 – September 31, 2012 Gagra Municipal (regional) Infrastructure Development (MID) ABKHAZIA # Municipality Region Project Title Gudauta Rehabilitation of Roads 1 Mtskheta 3.852 km; 11 streets : Mtskheta- : Mtanee Rehabilitation of Roads SOKHUMI : : 1$Mestia : 2 Dushet 2.240 km; 7 streets :: : ::: Rehabilitation of Pushkin Gulripshi : 3 Gori street 0.92 km : Chazhashi B l a c k S e a :%, Rehabilitaion of Gorijvari : 4 Gori Shida Kartli road 1.45 km : Lentekhi Rehabilitation of Nationwide Projects: Ochamchire SAMEGRELO- 5 Kareli Sagholasheni-Dvani 12 km : Highway - DCA Basisbank ZEMO SVANETI RACHA-LECHKHUMI rehabilitaiosn Roads in Oni Etseri - DCA Bank Republic Lia*#*# 6 Oni 2.452 km, 5 streets *#Sachino : KVEMO SVANETI Stepantsminda - DCA Alliance Group 1$ Gali *#Mukhuri Tsageri Shatili %, Racha- *#1$ Tsalenjikha Abari Rehabilitation of Headwork Khvanchkara #0#0 Lechkhumi - DCA Crystal Obuji*#*# *#Khabume # 7 Oni of Drinking Water on Oni for Nakipu 0 Likheti 3 400 individuals - Black Sea Regional Transmission ZUGDIDI1$ *# Chkhorotsku1$*# ]^!( Oni Planning Project (Phase 2) Chitatskaro 1$!( Letsurtsume Bareuli #0 - Georgia Education Management Project (EMP) Akhalkhibula AMBROLAURI %,Tsaishi ]^!( *#Lesichine Martvili - Georgia Primary Education Project (G-Pried) MTSKHETA- Khamiskuri%, Kheta Shua*#Zana 1$ - GNEWRC Partnership Program %, Khorshi Perevi SOUTH MTIANETI Khobi *# *#Eki Khoni Tskaltubo Khresili Tkibuli#0 #0 - HICD Plus #0 ]^1$ OSSETIA 1$ 1$!( Menji *#Dzveli -

ELECTION CODE of GEORGIA As of 24 July 2006

Strasbourg, 15 November 2006 CDL(2006)080 Engl. only Opinion No. 362 / 2005 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ELECTION CODE OF GEORGIA as of 24 July 2006 This is an unofficial translation of the Unified Election Code of Georgia (UEC) which has been produced as a reference document and has no legal authority. Only the Georgian language UEC has any legal standing. Incorporating Amendments adopted on: 28.11.2003 16.09.2004 Abkhazia and Adjara, Composition election admin; 12.10.2004 VL, Campaign funding, voting and counting procedures, observers’ rights, complaints and appeals, election cancellation and re-run 26.11.2004 Abolition of turnout requirement for mid-term elections and re-runs, drug certificate for MPs 24.12.2004 Rules for campaign and the media 22.04.2005 VL; CEC, DEC, PEC composition and functioning; 23.06.2005 Deadlines and procedures for filing complaints 09.12.2005 Election of Tbilisi Sacrebulo; plus miscellaneous minor changes 16.12.2005 Campaign fund; media outlets 23.12.2005 (1) Election System for Parliament, Multi-mandate Districts, Mid-term Elections, PEC, 23.12.2005 (2) Election of Sacrebulos (except Tbilisi) 06.2006 Changes pertaining to local elections; voting procedures, etc. 24.07.2006 Early convocation of PEC for 2006 local elections ORGANIC LAW OF GEORGIA Election Code of Georgia CONTENTS PART I............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Results of Mandarin Plantations Monitoring Damaged by Frost and Evaluation in Georgia

International Trends in Science and Technology AGRICULTURE RESULTS OF MANDARIN PLANTATIONS MONITORING DAMAGED BY FROST AND EVALUATION IN GEORGIA Khalvashi N., Chief scientist, Department of Biodiversity Monitoring and Conservation, Institute of Phytopathology and Biodiversity, Batumi Shota Rustaveli state university, Georgia Memarne G., Chief scientist, Institute of Phytopathology and Biodiversity, Batumi Shota Rustaveli state university, Georgia Baratashvili D., Professor, Department of biology, Batumi Shota Rustaveli state university, Georgia Kedelidze N., Senior scientist, Department of Biodiversity Monitoring and Conservation, Institute of Phytopathology and Biodiversity, Batumi Shota Rustaveli state university, Georgia Gabaidze M., Senior scientist, Department of Plant Diseases Monitoring, Molecular Biology, Institute of Phytopathology and Biodiversity, Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University, Georgia Gorjomeladze I., PhD student, Akaki Tsereteli State University, Kutaisi, Georgia DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_conf/30032021/7477 Abstract. In the paper is discussed the results of mandarin plantations monitoring damaged by frost in winter. Despite the centuries-old history of citrus production in Georgia, the danger of frost damage remains a major limiting factor for the spread of citrus. The monitoring revealed that although the temperature was quite critical for mandarin in February 2020 (-11-12°C, in some places -14°C), the frost damage to the plantations was not high, but was inhomogeneous. Observations revealed that the -

Georgia Primary Education Project

GEORGIA PRIMARY EDUCATION PROJECT BASELINE/IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Contract No. AID-114-C-09-00003 USAID COR: Medea Kakachia Chief of Party: Nancy Parks June 2013 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 1 Table of Contents The Context ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of Impact Baseline Study ............................................................................................................................. 3 Study Design ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Pilot and Control Group School Sampling and Selection Process ................................................................. 7 Selection of Students for Baseline Study ............................................................................................................. 10 Test Administration Manuals ................................................................................................................................... 10 Development of Reading and Math Diagnostic Assessment Tools .......................................................... -

Flash Floods

DREF final report Georgia: Flash Floods DREF operation n° MDRGE003 FF-2011-000071-GEO 22 December 2011 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Summary: CHF 59,960 has been allocated from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) on 25th of June 2011 to support the Georgia National Society in delivering immediate assistance to some 1,750 beneficiaries for a period of three months. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged In Western and Eastern Georgia many regions were affected by unceasing rains from 12 to 22 June 2011 with landslides that followed. Seven people lost their lives. Over 3,000 houses have been affected, with 1,500 of them badly damaged. The ground floors of 350 houses were made unsuitable for living due to water/ damage. Additionally, the mudslides and the water have damaged/ polluted farming soil, roads, bridges, canals, and water supply system and communication network. The residents of affected regions amounting to 70000 people have been cut off Affected population in Dusheti is receiving relief from the water and gas utility system. The water has items from DREF Operation. Photo: Georgian Red swept away several roads, leaving many settlements Cross Society isolated. -

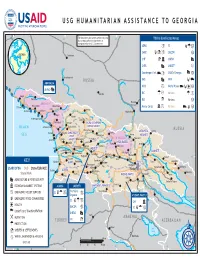

Georgia Program Maps 10/31/2008

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO GEORGIA 40° E 42° E The boundaries and names used on this map 44° E T'bilisi & Affected46° E Areas Majkop do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. ADRA a SC Ga I GEORGIA CARE a UMCOR a Cherkessk CHF IC UNFAO CaspianA Sea 44° CNFA A UNICEF J N 44° Kuban' Counterpart Int. Ea USAID/Georgia Aa N Karachayevsk RUSSIA FAO A WFP E ABKHAZIA E !0 Psou IOCC a World Vision Da !0 UNFAO A 0 Nal'chik IRC G J Various G a ! Gagra Bzyb' Groznyy RUSSIA 0 Pskhu IRD I Various a ! Nazran "ABKHAZIA" Novvy Afon Pitsunda 0 Omarishara Mercy Corps Ca Various E a ! Lata Sukhumi Mestia Gudauta!0 !0 Kodori Inguri Vladikavkaz Otap !0 Khaishi Kvemo-gulripsh Lentekhi !0 Tkvarcheli Dzhvari RACHA-LECHKHUMI-RACHA-LECHKHUMI- Terek BLACK Ochamchira Gali Tsalenjhikha KVEMOKVEMO SVANETISVANETI RUSSIA Khvanchkara Rioni MTSKHETA-MTSKHETA- Achilo Pichori Zugdidi SAMEGRELO-SAMEGRELO- Kvaisi Mleta SEA ZEMOZEMO Ambrolauri MTIANETIMTIANETI Pasanauri Alazani Khobi Tskhaltubo Tkibuli "SOUTH OSSETIA" Anaklia SVANETISVANETI Aragvi Qvirila SHIDASHIDA KARTLIKARTLI Senaki Kurta Artani Rioni Samtredia Kutaisi Chiatura Tskhinvali Poti IMERETIIMERETI Lanchkhuti Rioni !0 Akhalgori KAKHETIKAKHETI Chokhatauri Zestafoni Khashuri N Supsa Baghdati Dusheti N 42° Kareli Akhmeta Kvareli 42° Ozurgeti Gori Kaspi Borzhomi Lagodekhi KEY Kobuleti GURIAGURIA Bakhmaro Borjomi TBILISITBILISI Telavi Abastumani Mtskheta Gurdzhaani Belokany USAID/OFDA DoD State/EUR/ACE Atskuri T'bilisi Î! Batumi 0 AJARIAAJARIA Iori ! Vale Akhaltsikhe Zakataly State/PRM -

Restoration of Stepantsminda Museum (Kazbegi Municipality) Subproject Phase 2

Public Disclosure Authorized Restoration of Stepantsminda Museum (Kazbegi Municipality) Subproject Phase 2 Public Disclosure Authorized Sub-project Environmental and Social Screening and Environmental and Social Review Public Disclosure Authorized Third Regional Development Project Funded by the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized April, 2019 Subproject Description The Subproject (SP) considers restoration of three buildings of Alexander Kazbegi historical museum complex in the borough of Stepantsminda - historical museum building, Alexander Kazbegi Memorial House and Nikoloz Kazbegi (uncle of Alexander Kazbegi) house, as well as arrangement of the museum yard. Rehabilitation works for the complex were initiated in 2017, under the Regional Development Project III. The following works were completed under phase I of rehabilitation works: Al. Kazbegi House-Museum: - Wooden stairs, plaster and wood floor of the first story were removed in the interior. - Foundation was strengthened. - The vault existing on top of the access to southern balcony was rearranged. - The later period facing of northern part of the western façade of the building was removed. - Ceramic tile finishing of the balcony was removed. House of Nikoloz Kazbegi: - Plaster and wood floor of the first story were removed in the interior. - The old roof was removed and temporary roofing was arranged. - Two semi-circular staircases were removed. According to the new circumstances revealed during rehabilitation works, the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation -

GEORGIA Second Edition March 2010

WHO DOES WHAT WHERE IN DISASTER RISK REDUCTION IN GEORGIA Second edition March 2010 Georgian National Committee of Disaster Risk Reduction & Environment Sustainable Development FOREWORD Georgia is a highly disaster-prone country, which frequently experiences natural hazards (e.g. earthquakes, floods, landslides, mudflows, avalanches, and drought) as well as man-made emergencies (e.g. industrial accidents and traffic accidents). Compounding factors such as demographic change, unplanned urbanization, poorly maintained infrastructure, lax enforcement of safety standards, socio-economic inequities, epidemics, environmental degradation and climate variability amplify the frequency and intensity of disasters and call for a proactive and multi-hazard approach. Disaster risk reduction is a cross-cutting and complex development issue. It requires political and legal commitment, public understanding, scientific knowledge, careful development planning, responsible enforcement of policies and legislation, people-centred early warning systems, and effective disaster preparedness and response mechanisms. Close collaboration of policy-makers, scientists, urban planners, engineers, architects, development workers and civil society representatives is a precondition for adopting a comprehensive approach and inventing adequate solutions. Multi-stakeholder and inter-agency platforms can help provide and mobilize knowledge, skills and resources required for mainstreaming disaster risk reduction into development policies, for coordination of planning and programmes, -

(Upr) Mid-Term Progress Report of Georgia on Its Implementation of Recommendations Elaborated in January 2011

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia Human Rights Council UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW (UPR) MID-TERM PROGRESS REPORT OF GEORGIA ON ITS IMPLEMENTATION OF RECOMMENDATIONS ELABORATED IN JANUARY 2011 Tbilisi, December, 2013 UPR RECOMMENDATIONS Recommendation Rec. State Scope of the Competent Measures undertaken Recommendations and the obligation Body of the respective Rec. taken by treaty-based number Georgia bodies ACCESSION TO INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS 1. Consider accession to the remaining Brazil Ministry of At present, Georgia is a State Party to the core international human rights 105.1 Foreign Affairs various core international human rights instruments. instruments. Since 2011 Georgia has acceded to the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (in force for Georgia since March 22, 2012); Internal procedures necessary for ratification are in progress relating the following core international human rights instruments: UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol; Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness; International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families; Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse. 2. Consider the possibility of becoming a Argentina 1. Ministry of The process of ratification of the Convention party to the following international 105.2 Foreign Affairs on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is instruments: initiated and at present is going -

Realizing the Urban Potential in Georgia: National Urban Assessment

REALIZING THE URBAN POTENTIAL IN GEORGIA National Urban Assessment ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK REALIZING THE URBAN POTENTIAL IN GEORGIA NATIONAL URBAN ASSESSMENT ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2016 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2016. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9257-352-2 (Print), 978-92-9257-353-9 (e-ISBN) Publication Stock No. RPT168254 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Asian Development Bank. Realizing the urban potential in Georgia—National urban assessment. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2016. 1. Urban development.2. Georgia.3. National urban assessment, strategy, and road maps. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. This publication was finalized in November 2015 and statistical data used was from the National Statistics Office of Georgia as available at the time on http://www.geostat.ge The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Khulo Local Development Strategy 2018 - 2022

KHULO LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2018 - 2022 KHULO–PARADISE IN THE MOUNTAINS June 5, 2018 www.khulolag.ge KHULO LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2018-2012 Khulo Municipality Local Development Strategy was developed with financial support of European Union under the European Neighborhood Programme for Agriculture and Rural Development (ENPARD) and Czech republic development agency project: “Rural Development and Diversification in Khulo Municipality”. This project is implemented by Caritas Czech Republic in Georgia (CCRG) in partnership with Croatian rural development network – HMRR and PMC Research Center. The information and views set out in this document are those of the Czech Republic in Georgia (CCRG) and Khulo Local Action Group (LAG) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion and views of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 | P a g e KHULO LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2018-2012 Abbreviations LAG Local Action Group RDS Rural Development Strategy GEOSTAT Georgian National Statistics Office LDS Local Development Strategy DMP/DMO Destination Management Plan/Destination Management Organization MEPA Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture 3 | P a g e KHULO LOCAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 2018-2012 Contents Introduction and Summary .......................................................................................................................................................