The Revolt of the Upper Castes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A ,JUSTIFICATION of RESERVATION Forobcs (A CRI1''ique of SHO:URIE & ORS.)

GEN. EDITOR: DR. A. R. DESAI A ,JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATION FOROBCs (A CRI1''IQUE OF SHO:URIE & ORS.) MIHIRDESAI C.G. SHAll !\IE!\lORIAL TRUST PUBLICATION (20) C. G. Shah Memorial Trust Publication (20) A JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATIONS FOR OBCs by MIHIR DESAI Gen. EDITOR DR. A. R. DESAI. IN COLLABORATION WITH HUMAN RIGHTS & LAW NETWORK BOMBAY. DECEMBER 1990 C. G. Shah Memorial Trust, Bombay. · Distributors : ANTAR RASHTRIY A PRAKASHAN *Nambalkar Chambers, *Palme Place, Dr. A. R. DESAI, 2nd Floor, Calcutta-700 019 * Jaykutir, Jambhu Peth, (West Bengal) Taikalwadi Road, Dandia Bazar, · Mahim P.O., Baroda - 700 019 Bombay - 400 016 Gujarat State. * Mihir Desai Engineer House, 86, Appollo Street, Fort, Bom'Jay - 400 023. Price: Rs. 9 First Edition : 1990. Published by Dr. A. K. Desai for C. G. Shah Memorial Trust, Jaykutir, T.:;.ikaiwadi Road, Bombay - 400 072 Printed by : Sai Shakti(Offset Press) Opp. Gammon H::>ust·. Veer Savarkar Marg, Prabhadevi, Bombay - 400 025. L. A JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATIONS FOROOCs i' TABLE OF CONTENTS -.-. -.-....... -.-.-........ -.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-. S.No. Particulars Page Nos. -.- ..... -.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-. 1. Forward (i) - (v) 2. Preface (vi) - 3. Introduction 1 - 3 4. The N.J;. Government and 3 - 5' Mandai Report .5. Mandai Report 6 - 14 6. The need for Reservation 14 - 19 7. Is Reservation the Answer 19 - 27 8. The 10 Year time-limit .. 28 - 29 9. Backwardness of OBCs 29 - 39 10. Socia,l Backwardness and 39 - 40' Reservations 11. ·Criteria .for Backwardness 40 - 46 12. lnsti tutionalisa tion 47 - 50 of Caste 13. Economic Criteria 50 - 56 14. The Merit Myth .56 - 64 1.5. -

Aump Mun 3.0 All India Political Parties' Meet

AUMP MUN 3.0 ALL INDIA POLITICAL PARTIES’ MEET BACKGROUND GUIDE AGENDA : Comprehensively analysing the reservation system in the light of 21st century Letter from the Executive Board Greetings Members! It gives us immense pleasure to welcome you to this simulation of All India Political Parties’ Meet at Amity University Madhya Pradesh Model United Nations 3.0. We look forward to an enriching and rewarding experience. The agenda for the session being ‘Comprehensively analysing the reservation system in the light of 21st century’. This study guide is by no means the end of research, we would very much appreciate if the leaders are able to find new realms in the agenda and bring it forth in the committee. Such research combined with good argumentation and a solid representation of facts is what makes an excellent performance. In the session, the executive board will encourage you to speak as much as possible, as fluency, diction or oratory skills have very little importance as opposed to the content you deliver. So just research and speak and you are bound to make a lot of sense. We are certain that we will be learning from you immensely and we also hope that you all will have an equally enriching experience. In case of any queries feel free to contact us. We will try our best to answer the questions to the best of our abilities. We look forward to an exciting and interesting committee, which should certainly be helped by the all-pervasive nature of the issue. Hopefully we, as members of the Executive Board, do also have a chance to gain from being a part of this committee. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India Vani K. Borooah, Amaresh Dubey and Sriya Iyer ABSTRACT This article investigates the effect of jobs reservation on improving the eco- nomic opportunities of persons belonging to India’s Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Using employment data from the 55th NSS round, the authors estimate the probabilities of different social groups in India being in one of three categories of economic status: own account workers; regu- lar salaried or wage workers; casual wage labourers. These probabilities are then used to decompose the difference between a group X and forward caste Hindus in the proportions of their members in regular salaried or wage em- ployment. This decomposition allows us to distinguish between two forms of difference between group X and forward caste Hindus: ‘attribute’ differences and ‘coefficient’ differences. The authors measure the effects of positive dis- crimination in raising the proportions of ST/SC persons in regular salaried employment, and the discriminatory bias against Muslims who do not benefit from such policies. They conclude that the boost provided by jobs reservation policies was around 5 percentage points. They also conclude that an alterna- tive and more effective way of raising the proportion of men from the SC/ST groups in regular salaried or wage employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. INTRODUCTION In response to the burden of social stigma and economic backwardness borne by persons belonging to some of India’s castes, the Constitution of India allows for special provisions for members of these castes. -

In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism

“I recognized two people pulling away my daughter Shabana. My daughter was screaming in pain asking the men to leave her alone. My mind was seething with fear and fury. I could do nothing to help my daughter from being assaulted sexually and tortured to death. My daughter was like a flower, still to see life.Why did they have to do this to her? What kind of men are these? The monsters tore my beloved daughter to pieces.” Medina Mustafa Ismail Sheikh, then in Kalol refugee camp, Panchmahals District, Gujarat This report is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of Indians who have lost their homes, their loved ones or their lives because of the politics of hatred.We stand by those in India struggling for justice, and for a secular, democratic and tolerant future. 2 IN BAD FAITH? BRITISH CHARITY AND HINDU EXTREMISM INFORMATION FOR READERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A separate report summary is available from Any final conclusions of fact or expressions of www.awaazsaw.org. Each section of this opinion are the responsibility of Awaaz – South report also begins with a summary of main Asia Watch Limited alone. Awaaz – South Asia findings. Watch would like to thank numerous individuals and organizations in the UK, India and the US for Section 1 provides brief information on advice and assistance in the preparation of this Hindutva and shows Sewa International UK’s report. Awaaz – South Asia Watch would also like connections with the RSS. Readers familiar to acknowledge the insights of the report The with these areas can skip to: Foreign Exchange of Hate researched by groups in the US. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Draft Programme 1

India Summit 2015 India under Modi September 9th 2015 • Taj Palace Hotel • New Delhi One year after Narendra Modi became prime minister, much is changing in India. Mr Modi is a pre-eminent leader, the most dominant in decades: he wields an unusual degree of power over both his party and government, and his ability to guide reforms in India remains significant. Mr Modi has used his first year to make a series of grand, specific and welcome promises. He has pledged to deliver “good times”, meaning rapid economic recovery. He also promised strong national leadership, a high profile for India internationally, an end to the worst forms of corruption, the expansion of modern infrastructure and the creation of millions of new jobs. Mr Modi also created high expectations that he would deliver a more responsive bureaucracy, less red tape, a predictable tax regime and pro-business policies, especially to promote manufacturing. On many fronts, he has shown sharp improvements. India has made great economic gains since a downturn in 2013 under the previous government. As his government aims for an expansion of 7% to 8% annually, confidence is rising as a result of better monetary policy and improvements in general macroeconomic management. The IMF and other observers predict that India will shortly be growing faster than China. It is perhaps internationally that India has seen the most striking change. Mr Modi and his government have shown a new openness towards investors, and have tapped the increasingly influential Indian diaspora to promote closer diplomatic ties and more investment in India. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Ahom in India Aka in India Population: 1,341,000 Population: 11,000 World Popl: 1,341,000 World Popl: 11,400 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other Main Language: Assamese Main Language: Hruso Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 4.06% Chr Adherents: 26.74% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Translation Started www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Sairg - Wikimedia Source: Rev. T. Kampu "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arleng in India Arora (Sikh traditions) in India Population: 500,000 Population: 465,000 World Popl: 500,900 World Popl: 466,100 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other People Cluster: South Asia Sikh - other Main Language: Karbi Main Language: Punjabi, Eastern Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Other / Small Status: Minimally Reached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 19.74% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Mangal Rongphar Source: VikramRaghuvanshi - iStock "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for -

The Political Economy of Hindu Nationalism in India 1998-2004

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA 1998-2004 submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Politics and International Relations John Joseph Abraham Royal Holloway, University of London 1 2 Declaration of Authorship I John Joseph Abraham hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: John Joseph Abraham August 22, 2014 3 4 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to a number of people who have made this project possible. I thank my supervisors Dr. Yasmin Khan and Dr. Oliver Heath for their careful guidance, constant support and enthusiasm over these years. Thanks is also due to Dr. James Sloam for his insights at important stages of this project. Finally I would like to thank Dr. Tony Charles for his valuable support in the final stages of this work. I thank Dr. Nathan Widder under whose leadership the Department of Politics and International Relations has been a supportive environment and congenial forum for the development of ideas and Dr. Jay Mistry, Dr. Ben O'Loughlin, Dr. Sandra Halperin and Anne Uttley for the important roles they have played in my development as an academic scholar. Finally, thanks is due to my fellow researchers, Shyamal Kataria, Baris Gulmez, Didem Buhari, Celine Tschirhart, Ali Mosadegh Raad, Braham Prakash Guddu and Mark Pope for the many useful conversations and sympathetic understanding. This project would have not been possible but for the help of my family. I would like to thank my parents Abraham and Valsa Joseph as well as George and Annie Mathew for their constant encouragement and eager support. -

'A Battle Between Hindutva and Hinduism Is Coming' | the Indian

‘A battle between Hindutva and Hinduism is comingʼ | The Indian Express 8/28/18, 1217 PM ‘A battle between Hindutva and Hinduism is coming’ In a wide-ranging conversation, Walter Andersen speaks of the changing nature of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, how it was influenced by its different sarsangchalaks and the challenges that lie ahead of the organisation Walter Andersen is on the faculty of the Johns Hopkins University, Washington, and Tongji University, Shanghai. Walter Andersen is, perhaps, the only scholar to have observed, or studied, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) for nearly five decades. In intellectual circles, it is normally believed that as an organisation, the RSS is https://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/books/a-battle-between-hindutva-and-hinduism-is-coming-walter-andersen-rss-5301109/ Page 1 of 14 ‘A battle between Hindutva and Hinduism is comingʼ | The Indian Express 8/28/18, 1217 PM impervious and impenetrable. Its functioning is not available for scholarly scrutiny, unless one happens to be an insider or a firm sympathiser. That is why the publication of The RSS: A View to the Inside, a new book Andersen has co-written with Sridhar Damle, is a true intellectual event (The duo had also produced a book, Brotherhood in Saffron, three decades back). Andersen is on the faculty of the Johns Hopkins University, Washington, and Tongji University, Shanghai, and before that, he was a leading South Asia specialist of the US State Department for over two decades. At a Gurgaon hotel where he is staying, he recently spoke with Ashutosh Varshney, professor of Political Science, Brown University and contributing editor, The Indian Express. -

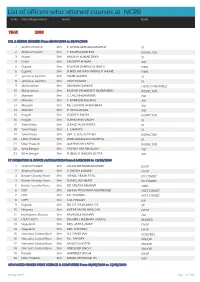

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Indigenist Mobilization

INDIGENIST MOBILIZATION: ‘IDENTITY’ VERSUS ‘CLASS’ AFTER THE KERALA MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT? LUISA STEUR CEU eTD Collection PHD DISSERTATION DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY (BUDAPEST) 2011 CEU eTD Collection Cover photo: AGMS activist and Paniya workers at Aralam Farm, Kerala ( Luisa Steur, 2006) INDIGENIST MOBILIZATION: ‘IDENTITY’ VERSUS ‘CLASS’ AFTER THE KERALA MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT? by Luisa Steur Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Judit Bodnar Professor Prem Kumar Rajaram Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection 2011 Statement STATEMENT I hereby state that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, 2011. CEU eTD Collection Indigenist mobilization: ‘Identity’ versus ‘class’ after the Kerala model of development? i Abstract ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the recent rise of "adivasi" (indigenous/tribal) identity politics in the South Indian state of Kerala. It discusses the complex historical baggage and the political risks attached to the notion of "indigeneity" in Kerala and poses the question why despite its draw- backs, a notion of indigenous belonging came to replace the discourse of class as the primary framework through which adivasi workers now struggle for their rights. The thesis answers this question through an analysis of two inter-linked processes: firstly, the cyclical social movement dynamics of increasing disillusionment with - and distantiation from - the class-based platforms that led earlier struggles for emancipation but could not, once in government, structurally alter existing relations of power.