Building the New Libya: Lessons to Learn and to Unlearn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 ! ! ! TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 ESSAY ONE COMPETING JIHADIST ORGANISATIONS AND NETWORKS 6 Islamic State, Al-Qaeda, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar al-Sharia in Libya Stefano Torelli and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY TWO POLITICAL PARTY OR ARMED FACTION? 31 The Future of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood Valentina Colombo, Giuseppe Dentice and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY THREE MAPPING RADICAL ISLAMIST MILITIAS IN LIBYA 53 Wolfgang Pusztai and Arturo Varvelli ESSAY FOUR THE EXPLOITATION OF MIGRATION ROUTES TO EUROPE 73 Human Trafficking Through Areas of Libya Affected by Fundamentalism Nancy Porsia ABOUT THE AUTHORS 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 2 LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL 3 DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS FOREWORD ! ! This publication is a compilation of four different essays, edited by Dr. Arturo Varvelli PhD, which from part of a series of studies undertaken by EFD to analyse the nature and spread of the phenomenon of radicalisation in the European Eastern and Southern neighbourhoods. It focuses on Libya and assesses the current situation on the ground through a number of diverse and varied prisms. It identifies patterns and trends as well as specific local and regional developments in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the situation of radicalisation in post-Ghadaffi Libya and the extent to which this may be contributing to regional as well as international instability Months of acute political turmoil in Libya following the fall of the Qaddafi regime, compounded by a weak national identity as well as legacies from the civil war in 2011 which ended Qaddafi’s 42-year rule, have resulted in Libya becoming a failed state with a strong radical Islamist presence. -

Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy

Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Christopher M. Blanchard Acting Section Research Manager June 6, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33142 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Libya: Unrest and U.S. Policy Summary Over 40 years ago, Muammar al Qadhafi led a revolt against the Libyan monarchy in the name of nationalism, self-determination, and popular sovereignty. Opposition groups citing the same principles are now revolting against Qadhafi to bring an end to the authoritarian political system he has controlled in Libya for the last four decades. The Libyan government’s use of force against civilians and opposition forces seeking Qadhafi’s overthrow sparked an international outcry and led the United Nations Security Council to adopt Resolution 1973, which authorizes “all necessary measures” to protect Libyan civilians. The United States military is participating in Operation Unified Protector, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military operation to enforce the resolution. Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan and other partner governments also are participating. Qadhafi and his supporters have described the uprising as a foreign and Islamist conspiracy and are attempting to outlast their opponents. Qadhafi remains defiant amid coalition air strikes and defections. His forces continue to attack opposition-held areas. Some opposition figures have formed an Interim Transitional National Council (TNC), which claims to represent all areas of the country. They seek foreign political recognition and material support. Resolution 1973 calls for an immediate cease-fire and dialogue, declares a no-fly zone in Libyan airspace, and authorizes robust enforcement measures for the arms embargo on Libya established by Resolution 1970 of February 26. -

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy Updated April 13, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33142 SUMMARY RL33142 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy April 13, 2020 Libya’s political transition has been disrupted by armed non-state groups and threatened by the indecision and infighting of interim leaders. After a uprising ended the 40-plus-year rule of Christopher M. Blanchard Muammar al Qadhafi in 2011, interim authorities proved unable to form a stable government, Specialist in Middle address security issues, reshape the country’s finances, or create a viable framework for post- Eastern Affairs conflict justice and reconciliation. Insecurity spread as local armed groups competed for influence and resources. Qadhafi compounded stabilization challenges by depriving Libyans of experience in self-government, stifling civil society, and leaving state institutions weak. Militias, local leaders, and coalitions of national figures with competing foreign patrons remain the most powerful arbiters of public affairs. An atmosphere of persistent lawlessness has enabled militias, criminals, and Islamist terrorist groups to operate with impunity, while recurrent conflict has endangered civilians’ rights and safety. Issues of dispute have included governance, military command, national finances, and control of oil infrastructure. Key Issues and Actors in Libya. After a previous round of conflict in 2014, the country’s transitional institutions fragmented. A Government of National Accord (GNA) based in the capital, Tripoli, took power under the 2015 U.N.- brokered Libyan Political Agreement. Leaders of the House of Representatives (HOR) that were elected in 2014 declined to endorse the GNA, and they and a rival interim government based in eastern Libya have challenged the GNA’s authority with support from the Libyan National Army/Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LNA/LAAF) movement. -

The Political Role of Libyan Youth During and After the Revolution

Youth, Revolt, Recognition The Young Generation during and after the “Arab Spring” Edited by Isabel Schäfer From The Core To The Fringe? The Political Role of Libyan Youth During And After The Revolution by Anna Lührmann MIB-Edited Volume Berlin 2015 Projekt „Mittelmeer Institut Berlin (MIB)“ Project „Mediterranean Institute Berlin (MIB)“ Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin Dr. Isabel Schäfer Mail: [email protected] The MIB publication series is available online at https://www.mib.hu-berlin.de/ © 2015, MIB/HU, the author(s): Inken Bartels Charlotte Biegler-König Gözde Böcu Daniel Farrell Bachir Hamdouch Valeska Henze Wai Mun Hong Anna Lührmann Isabel Schäfer Carolina Silveira Layout: Jannis Grimm Maher El-Zayat Schäfer, Isabel, ed. (2015): Youth, Revolt, Recognition – The Young Generation during and after the "Arab Spring". Berlin: Mediterranean Institute Berlin (MIB)/HU Berlin. MIB Edited Volume | March 2015 Project “Mediterranean Institute Berlin”, Humboldt University Berlin; www.mib.hu-berlin.de HU Online Publikation, Open Access Programm der HU. To link to this article: urn:nbn:de:kobv:11-100228053 www.mib.hu-berlin.de/publikationen Table of Contents Introduction - Isabel Schäfer 1 Part I – Theoretical Perspectives 5 On the Concept of Youth – Some Reflections on Theory - Valeska Henze 5 Part II – Youth and Politics in the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean 17 Youth as Political Actors after the “Arab Spring”: The Case of Tunisia - Carolina Silveira 17 From The Core -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Libya Country Report Matteo Capasso, Jędrzej Czerep, Andrea Dessì, Gabriella Sanchez

Libya Country Report Matteo Capasso, Jędrzej Czerep, Andrea Dessì, Gabriella Sanchez This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 769886 DOCUMENT INFORMATION Project Project acronym: EU-LISTCO Project full title: Europe’s External Action and the Dual Challenges of Limited Statehood and Contested Order Grant agreement no.: 769886 Funding scheme: H2020 Project start date: 01/03/2018 Project duration: 36 months Call topic: ENG-GLOBALLY-02-2017 Shifting global geopolitics and Europe’s preparedness for managing risks, mitigation actions and fostering peace Project website: https://www.eu-listco.net/ Document Deliverable number: XX Deliverable title: Libya: A Country Report Due date of deliverable: XX Actual submission date: XXX Editors: XXX Authors: Matteo Capasso, Jędrzej Czerep, Andrea Dessì, Gabriella Sanchez Reviewers: XXX Participating beneficiaries: XXX Work Package no.: WP4 Work Package title: Risks and Threats in Areas of Limited Statehood and Contested Order in the EU’s Eastern and Southern Surroundings Work Package leader: EUI Work Package participants: FUB, PSR, Bilkent, CIDOB, EUI, Sciences Po, GIP, IDC, IAI, PISM, UIPP, CED Dissemination level: Public Nature: Report Version: 1 Draft/Final: Final No of pages (including cover): 38 2 “More than ever, Libyans are now fighting the wars of other countries, which appear content to fight to the last Libyan and to see the country entirely destroyed in order to settle their own scores”1 1. INTRODUCTION This study on Libya is one of a series of reports prepared within the framework of the EU- LISTCO project, funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme. -

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYIA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 About the European Foundation for Democracy The European Foundation for Democracy is a Brussels-based policy institute dedicated to upholding Europe’s fundamental values of freedom and equality, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion. Today these principles are being challenged by a number of factors, among them rapid social change as a result of high levels of immigration from cultures with different customs, a rise in intolerance on all sides, an increasing sense of a conflict of civilisations and the growing influence of radical, extremist ideologies worldwide. We work with grassroots activists, media, policy experts and government officials throughout Europe to identify constructive approaches to addressing these challenges. Our goal is to ensure that the universal values of the Enlightenment –religious tolerance, political pluralism, individual liberty and government by demo- cracy – remain the core foundation of Europe’s prosperity and welfare, and the basis on which diverse cultures and opinions can interact peacefully. About the Counter Extremism Project The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) is a not-for-profit, non-partisan, international policy organization formed to address the threat from extremist ideology. It does so by pressuring financial support networks, countering the narrative of extremists and their online recruitment, and advocating for effective laws, policies and regula- tions. CEP uses its research and analytical expertise to build a global movement against the threat to pluralism, peace and tolerance posed by extremism of all types. In the United States, CEP is based in New York City with a team in Washington, D.C. -

Libya's Fight for Survival

LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 LIBYA’S FIGHTLIBYA’S FOR SURVIVAL: DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS About the European Foundation for Democracy The European Foundation for Democracy is a Brussels-based policy institute dedicated to upholding Europe’s fundamental values of freedom and equality, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion. We work with grassroots activists, media, policy experts and government officials throughout Europe to identify constructive approaches to addressing these challenges. Our goal is to ensure that the universal values of the Enlightenment – political pluralism, individual liberty and government by democracy and religious tolerance – remain the core foundation of Europe’s prosperity and welfare, and the basis on which diverse cultures and opinions can interact peacefully. About the Counter Extremism Project The Counter Extremism Project is a not-for-profit, non-partisan, international policy organi- sation formed to address the threat from extremist ideology. It does so by pressuring financial support networks, countering the narrative of extremists and their online recruitment, and advo- cating for effective laws, policies and regulations. CEP uses its research and analytical expertise to build a global movement against the threat to pluralism, peace and tolerance posed by extremism of all types. In the United States, CEP is based in New York City with a team in Washington, D.C. LIBYA’S FIGHT FOR SURVIVAL DEFEATING JIHADIST NETWORKS September 2015 Edited by Arturo Varvelli -

Did the R2P Foster Violence in Libya?

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13 Issue 2 Rethinking Genocide, Mass Atrocities, and Political Violence in Africa: New Directions, Article 7 New Inquiries, and Global Perspectives 6-2019 Did the R2P Foster Violence in Libya? Alan Kuperman University of Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Kuperman, Alan (2019) "Did the R2P Foster Violence in Libya?," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 2: 38-57. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.13.2.1705 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol13/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Did the R2P Foster Violence in Libya? Alan Kuperman University of Texas Austin, Texas, USA In the early 1990s, the relationship between genocidal violence and international humanitarian intervention was understood simplistically. Such intervention was viewed as always a response to, and never a cause of, inter-group violence. Well-intentioned intervention was expected reliably to reduce harm to civilians. Thus, the only obstacle to saving lives was believed to be inadequate political will for intervention. This quaint notion was popularized in mass-market books,1 and it later gave rise to the “Responsibility to Protect” norm.2 By the mid-1990s, however, scholars had discovered that the causal relationship between intervention and genocidal violence was more complicated. -

Ansar Al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) Type Of

Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) Type of Organization: insurgent, non-state actor, religious, social services provider, terrorist, violent Ideologies and Affiliations: Islamist, jihadist, Qutbist, Salafist, Sunni, Takfiri Place(s) of Origin: Libya Year of Origin: 2012 Founder(s): Abu Sufyan Bin Qumu (founder of Ansar al-Sharia in Derna);1 Mohamed al-Zahawi, Nasser al-Tarshani, and other Libyan Islamists (founders of Ansar al-Sharia Benghazi) Place(s) of Operation: Libya Also Known As: • Ansar al-Charia in Libya 2 • Katibat Ansar al-Charia 3 • Katibat Ansar al-Sharia 4 • Partisans of Islamic Law in Libya5 • Partisans of Sharia in Libya 6 • Supporters of Islamic Law in Libya7 • Supporters of Sharia in Libya 8 Executive Summary: Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) is a violent jihadist group that seeks to implement sharia (Islamic law) in Libya. ASL is the union of two smaller groups, the Ansar al-Sharia Brigade in Benghazi (ASB) and Ansar al-Sharia Derna (ASD), each formed in 2011 after the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. In 2012, ASB and ASD, 1 Aaron Y. Zelin, “Know Your Ansar Al-Sharia,” Foreign Policy, September 21, 2012, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/09/21/know_your_ansar_al_sharia. 2 “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Two Entities to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, November 19, 2014, http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11659.doc.htm. 3 “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Two Entities to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, November 19, 2014, http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11659.doc.htm. 4 “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Two Entities to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, November 19, 2014, http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11659.doc.htm. -

Citizenship Rights and the Arab Uprisings: Towards a New Political Order

CITIZENSHIP RIGHTS AND THE ARAB UPRISINGS: TOWARDS A NEW POLITICAL ORDER January 2015 Report written by Dr. Roel Meijer in consultation with Laila al-Zwaini Clients of Policy and Operations Evaluations Department (IOB) Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Netherlands I. Table of Contents I. Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 1 II. Biographical information authors ................................................................................................... 4 III. List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 5 Figures Figure 1. Overlapping consensus of political currents in the Arab world ........................................... 38 Figure 2. Virtuous circle of citizenship ................................................................................................ 41 Figure 3. Index of the results of the Arab uprisings ............................................................................ 72 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1 FACTORS AND ACTORS BLOCKING A DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION ................................................. 8 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 8 1.1 Islam ................................................................................................................................... -

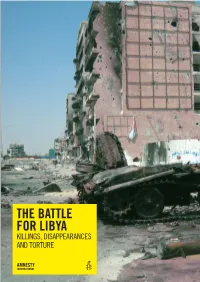

The Battle for Libya

THE BATTLE FOR LIBYA KILLINGS, DISAPPEARANCES AND TORTURE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2011 Index: MDE 19/025/2011 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : Misratah, Libya, May 2011 © Amnesty International amnesty.org CONTENTS Abbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5 Introduction .................................................................................................................7 1. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution”.................................13 2. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................23 3. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................34 4.