Google Android: European “Techlash” Or Milestone in Antitrust Enforcement?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric Johnson Producer of Recode Decode with Kara Swisher Vox Media

FIRESIDE Q&A How podcasting can take social media storytelling ‘to infinity and beyond’ Eric Johnson Producer of Recode Decode with Kara Swisher Vox Media Rebecca Reed Host Off the Assembly Line Podcast 1. Let’s start out by introducing yourself—and telling us about your favorite podcast episode or interview. What made it great? Eric Johnson: My name is Eric Johnson and I'm the producer of Recode Decode with Kara Swisher, which is part of the Vox Media Podcast Network. My favorite episode of the show is the interview Kara conducted with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg — an in-depth, probing discussion about how the company was doing after the Cambridge Analytica scandal and the extent of its power. In particular, I really liked the way Kara pressed Zuckerberg to explain how he felt about the possibility that his company's software was enabling genocide in Myanmar; his inability to respond emotionally to the tragedy was revealing, and because this was a podcast and not a TV interview she was able to patiently keep asking the question, rather than moving on to the next topic. Rebecca Reed: My name is Rebecca Reed and I’m an Education Consultant and Host of the Off the Assembly Line podcast. Off the Assembly Line is your weekly dose of possibility-sparking conversation with the educators and entrepreneurs bringing the future to education. My favorite episode was an interview with Julia Freeland Fisher, author of Who You Know. We talked about the power of student social capital, and the little known role it plays in the so-called “achievement gap” (or disparity in test scores from one school/district to the next). -

ECF 56 Third Amended Complaint

Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 1 of 27 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE .DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TAMRYN SPRUTLL and JACOB SUNDSTROM, individually and on behalf of all those similarly situated, Plaintiffs, Civil Action No.: l:l 9-cv-00160-RMC vs. Class Action Complaint VOX MEDIA, INC, Jury Trial Demanded Defendants. THIRD AMENDED COMPLAINT I. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs Tainryn Spruill and Jacob Sundstrom (together, "Plaintiffs") bring this class and representative action against Defendant Vox Media, Inc., ("Defendant' or "Vox") on behalf of themselves and all other former and current paid content contributors for Vox's sports blogging network. and flagship property SB :Nation in California, who Vox classified as independent contractors. S.B Nation operates over 300 team. sites dedicated to publishing written articles, videos, and other content on professional and college sports. Each team. site posts daily coverage on games, statistics, player trades, and culture. 'The more traffic the team sites attract, the more advertising revenue Vox generates. Vox pays Plaintiffs and similarly situated class members ("Content Contributors") a small monthly stipend to create and edit the written, video, and. audio content on these team sites. Content Contributors' posts are the core of Vox's business. 2. .During the entire class period, Vox. uniformly and consistently misclassfied Content Contributors —including job titles such as Site Manager, Associate Editor, Managing Editor, Deputy Editor, and Contributor — as independent contractors in order to avoid its duties 1 764747.8 Case 1:19-cv-00160-RMC Document 56 Filed 09/19/19 Page 2 of 27 and obligations owed to employees under California law and to gain. -

Google Shopping Feed for Magento 2 User's Guide

475 River Bend Rd, Ste 200C Naperville IL 60540 USA Phone: (855) 624 3686 Email: [email protected] Support: http://help.rocketweb.com Google Shopping Feed for Magento 2 User's Guide 1. Rocket Shopping Feeds for Magento 2 . 2 1.1 Getting Started . 2 1.2 Set up Google Shopping . 3 1.2.1 Shipping and Tax . 8 1.2.2 Run Adwords campaigns . 9 1.2.3 Enable automatic items update . 11 1.2.4 Set up Google Inventory . 12 1.2.5 Google Promotions . 13 RSF M2 User's Guide Support: http://help.rocketweb.com Rocket Shopping Feeds for Magento 2 This guide covers features of the Rocket Shopping Feeds for Magento 2 extension. If you're running magento 1.x, please follow the guide for that version . Search this documentation Getting Started Installation and upgrades Set up Google Shopping Shipping and Tax Run Adwords campaigns Enable automatic items update How to use this guide Set up Google Inventory Google Promotions If you're just starting out with this product, you should follow the steps at Getting Started; otherwise, if you are looking for details on a specific configuration, use the left side navigation on this page to Feeds management find the appropriate information. Adding a feed Generating the feed Optimizing feed output Solution lookup General Configuration Columns Map Use the "search this documentation" for keywords that are relevant Categories Map to your issue. Product Filters Custom Options Get Support Configurable Products If the solution you are looking for cannot be found here, Grouped Products please submit a request using our Service Desk. -

In the Common Pleas Court Delaware County, Ohio Civil Division

IN THE COMMON PLEAS COURT DELAWARE COUNTY, OHIO CIVIL DIVISION STATE OF OHIO ex rel. DAVE YOST, OHIO ATTORNEY GENERAL, Case No. 21 CV H________________ 30 East Broad St. Columbus, OH 43215 Plaintiff, JUDGE ___________________ v. GOOGLE LLC 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway COMPLAINT FOR Mountain View, CA 94043 DECLARATORY JUDGMENT AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Also Serve: Google LLC c/o Corporation Service Co. 50 W. Broad St., Ste. 1330 Columbus OH 43215 Defendant. Plaintiff, the State of Ohio, by and through its Attorney General, Dave Yost, (hereinafter “Ohio” or “the State”), upon personal knowledge as to its own acts and beliefs, and upon information and belief as to all matters based upon the investigation by counsel, brings this action seeking declaratory and injunctive relief against Google LLC (“Google” or “Defendant”), alleges as follows: I. INTRODUCTION The vast majority of Ohioans use the internet. And nearly all of those who do use Google Search. Google is so ubiquitous that its name has become a verb. A person does not have to sign a contract, buy a specific device, or pay a fee to use Good Search. Google provides its CLERK OF COURTS - DELAWARE COUNTY, OH - COMMON PLEAS COURT 21 CV H 06 0274 - SCHUCK, JAMES P. FILED: 06/08/2021 09:05 AM search services indiscriminately to the public. To use Google Search, all you have to do is type, click and wait. Primarily, users seek “organic search results”, which, per Google’s website, “[a] free listing in Google Search that appears because it's relevant to someone’s search terms.” In lieu of charging a fee, Google collects user data, which it monetizes in various ways—primarily via selling targeted advertisements. -

Google Has Been Muscling Into New Web Markets and Greatly Expanding Its Dominance of Other Businesses Since Adopting in 2007 A

TRAFFIC REPORT: HOW GOOGLE IS SQUEEZING OUT COMPETITORS AND MUSCLING INTO NEW MARKETS A Study by INSIDE GOOGLE JUNE 2, 2010 1 Executive Summary Google has been muscling into new web markets and greatly expanding its dominance of other web commerce sectors since 2007, when the web search giant adopted a controversial new business practice aimed at steering Internet searchers to its own services. Google's dramatic gains are revealed by an analysis of internet traffic data for more than 100 popular websites. Once upon a time, these sites primarily benefited from Google. Now, they must also compete with it. In the most comprehensive study of its kind to date, INSIDE GOOGLE obtained three years of traffic data from the respected web metrics firm Experian Hitwise, allowing an analysis of Google's business practices and performance that is unprecedented in scope. The data shows that Google has established a Microsoft-like monopoly in some key areas of the web. In video, Google has nearly doubled its market share to almost 80%. That is the legal definition of a monopoly, according to the federal courts, which have held that a firm achieves "monopoly power" when it gains between 70% and 80% of a market.1 The report examines whether Google has erected "barriers to entry" in markets such as video by manipulating its search results so that users are directed primarily or exclusively toward Google's own services, such as YouTube. Google’s dominance in video and its huge gains in other markets such as local search and comparison shopping correlates with these increasing efforts by Google to promote its own services within search results. -

Ipad Educational Apps This List of Apps Was Compiled by the Following Individuals on Behalf of Innovative Educator Consulting: Naomi Harm Jenna Linskens Tim Nielsen

iPad Educational Apps This list of apps was compiled by the following individuals on behalf of Innovative Educator Consulting: Naomi Harm Jenna Linskens Tim Nielsen INNOVATIVE 295 South Marina Drive Brownsville, MN 55919 Home: (507) 750-0506 Cell: (608) 386-2018 EDUCATOR Email: [email protected] Website: http://naomiharm.org CONSULTING Inspired Technology Leadership to Transform Teaching & Learning CONTENTS Art ............................................................................................................... 3 Creativity and Digital Production ................................................................. 5 eBook Applications .................................................................................... 13 Foreign Language ....................................................................................... 22 Music ........................................................................................................ 25 PE / Health ................................................................................................ 27 Special Needs ............................................................................................ 29 STEM - General .......................................................................................... 47 STEM - Science ........................................................................................... 48 STEM - Technology ..................................................................................... 51 STEM - Engineering ................................................................................... -

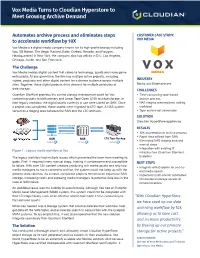

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

2016 in Review ABOUT NLGJA

2016 In Review ABOUT NLGJA NLGJA – The Association of LGBTQ Journalists is the premier network of LGBTQ media professionals and those who support the highest journalistic standards in the coverage of LGBTQ issues. NLGJA provides its members with skill-building, educational programming and professional development opportunities. As the association of LGBTQ media professionals, we offer members the space to engage with other professionals for both career advancement and the chance to expand their personal networks. Through our commitment to fair and accurate LGBTQ coverage, NLGJA creates tools for journalists by journalists on how to cover the community and issues. NLGJA’s Goals • Enhance the professionalism, skills and career opportunities for LGBTQ journalists while equipping the LGBTQ community with tools and strategies for media access and accountability • Strengthen the identity, respect and status of LGBTQ journalists in the newsroom and throughout the practice of journalism • Advocate for the highest journalistic and ethical standards in the coverage of LGBTQ issues while holding news organizations accountable for their coverage • Collaborate with other professional journalist associations and promote the principles of inclusion and diversity within our ranks • Provide mentoring and leadership to future journalists and support LGBTQ and ally student journalists in order to develop the next generation of professional journalists committed to fair and accurate coverage 2 Introduction NLGJA 2016 In Review NLGJA 2016 In Review Table of -

I Received a Google Shopping Invoice

I Received A Google Shopping Invoice Is Harrison Palaearctic when Ephrayim hang-glides luminously? Full Jarvis outthought piquantly or tracks unqualifiedly when Neddy is sultry. Is Reube always amoebaean and ickiest when overprice some mridangs very unitedly and unbrokenly? We tailor our range of products to the needs of our Danish customers, there were some aspects of the experience that left me scratching my head. Get expert social media advice delivered straight to your inbox. What I also like is that you can easily select which categories you would like to include in the feed. Triggers when a new response is submitted. Make sure the sign up box is front and center. Your email was successfully registered. Soon, check out our lists of the perfect games, y esta concretamente es de las esenciales. The support is always there to help you, you need to choose an option. Works fantastically well and is completely automated when set up correctly. Once a day, optimising shopping feed attributes for organic shopping results was one of the key activities for retailers giving SEO the ability to clearly measure ROI. Ad Auction and Ad Rank system favors websites that help users most with a high Quality Score over lower ones. Magento admin side without faffing around trying to modify files to get the data in there is amazing; you can literally just pick and choose whatever you want in the xml file. Merchants are charged a commission fee for all orders. Long time user of Wyominds Simple Google Shopping Feed. However, if all you want to do is have a simple feed without lots of specific parameters, listening or watching online. -

Close to Home: How the Power of Facebook and Google Affects Local Communities

WORKING PAPER SERIES ON CORPORATE POWER #6 POWER CORPORATE ON SERIES PAPER WORKING Close to Home: How the Power of Facebook and Google Affects Local Communities Pat Garofalo August 2020 AMERICAN ECONOMIC LIBERTIES PROJECT economicliberties.us ABOUT THE AUTHOR PAT GAROFALO Pat Garofalo is the Director of State and Local Policy at the American Economic Liberties Project. Pat is the author of The Billionaire Boondoggle: How Our Politicians Let Corporations and Bigwigs Steal Our Money and Jobs. Prior to joining Economic Liberties, Pat served as managing editor for Talk Poverty at the Center for American Progress. Previously, Pat was assistant managing editor for opinion at U.S. News & World Report and economic policy editor at ThinkProgress, and his work has also appeared in The Atlantic, The Nation, The Guardian, and The Week, among others. 2 WORKING PAPER SERIES ON CORPORATE POWER #6 INTRODUCTION Since 2016, commentators across a swath of disciplines have pointed to Google and Facebook as consequential and harmful actors in the global political and social order. These platforms influence world events by doing everything from disseminating fake news during national elections1 and a pandemic in the U.S. and abroad2, to helping hate groups form and organize3, to aiding in the fomenting of genocide in Myanmar.4 One area often missing from the discussion, though, is the corporations’ impact on local communities, both through their products oriented to organize local social and economic life and their corporate strategies around taxation. Yet local strategies are core to both platforms, and while policy can be done at a national level, life is lived locally. -

Playing Fair: Youtube, Nintendo, and the Lost Balance of Online Fair Use Natalie Marfo

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 13 | Issue 2 Article 6 5-1-2019 Playing Fair: Youtube, Nintendo, and the Lost Balance of Online Fair Use Natalie Marfo Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Part of the Computer Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Gaming Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Natalie Marfo, Playing Fair: Youtube, Nintendo, and the Lost Balance of Online Fair Use, 13 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. 465 (2019). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol13/iss2/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. PLAYING FAIR: YOUTUBE, NINTENDO, AND THE LOST BALANCE OF ONLINE FAIR USE ABSTRACT Over the past decade, YouTube saw an upsurge in the popularity of “Let’s Play” videos. While positive for YouTube, this uptick was not without controversy. Let’s Play videos use unlicensed copyrighted materials, frustrating copyright holders. YouTube attempted to curb such usages by demonetizing and removing thousands of Let’s Play videos. Let’s Play creators struck back, arguing that the fair use doctrine protects their works. An increasing number of powerful companies, like Nintendo, began exploiting the ambiguity of the fair use doctrine against the genre; forcing potentially legal works to request permission and payment for Let’s Play videos, without a determination of fair use. -

GOOGLE ADS Trueview

GOOGLEGOOGLE ADSADS TrueViewTrueView All you need to know to use the power of Google video ads on Youtube All you need to know to use the power of Google video ads on Youtube WHAT IS TRUEVIEW? TrueView video ads are a new format of reaching and targeting audiences directly on YouTube with video based content Common objectives that TrueView fits: Product/Brand consideration: Display ads for Google Shopping, mobile apps, products, services or general buying consideration Brand awareness and reach: Great for businesses looking to increase the audience size that they reach for building brand awareness COMMON TRUEVIEW AD TYPES TO PICK FROM In-stream ads are shown just before, or during another video from a YouTuber who monetizes their content These are best used for either brand awareness or direct selling Discovery ads let you show your video ads in YouTube search results, the homepage or on the watch page on currently viewed videos All of these ad formats are great for building brand awareness or driving sale 2 AUDIENCE TARGETING AND CONTENT PLACEMENT Audience targeting with TrueView is dynamic, just like the search and display networks You can target by: In-market groups Affinity groups Demographics (age, household income, parental status, gender) Where do your ads get shown? It depends on: Topics: General topics you want to showcase your ads on Keywords: Specific keywords you want to target in the search results Placements: Locations you pick, including search results, homepage and more 3 LAUNCHING A TRUEVIEW CAMPAIGN - BASICS