74 Vieira Norman Angell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

The Problem of War Aims and the Treaty of Versailles Callaghan, JT

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository The problem of war aims and the Treaty of Versailles Callaghan, JT Titl e The problem of war aims and the Treaty of Versailles Aut h or s Callaghan, JT Typ e Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/46240/ Published Date 2 0 1 8 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non- commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected] . 13 The problem of war aims and the Treaty of Versailles John Callaghan Why did Britain go to war in 1914? The answer that generated popular approval concerned the defence of Belgian neutrality, defiled by German invasion in the execution of the Schlieffen Plan. Less appealing, and therefore less invoked for public consumption, but broadly consistent with this promoted justification, was Britain’s long-standing interest in maintaining a balance of power on the continent, which a German victory would not only disrupt, according to Foreign Office officials, but replace with a ‘political dictatorship’ inimical to political freedom.1 Yet only 6 days before the British declaration of war, on 30 July, the chairman of the Liberal Foreign Affairs Group, Arthur Ponsonby, informed Prime Minister Asquith that ‘nine tenths of the [Liberal] party’ supported neutrality. -

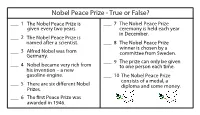

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

Sir Norman Angell Collection Correspondence Box 1 A. and C

Sir Norman Angell Collection Correspondence Box 1 A. and C. Black (Who's Who). 1911, 1963. A. Quick & Co., Ltd. 1934. A.T. Ferrell & Co. 1949. A.W. Gamage, Ltd. 1925. Aaron, Stanley. 1937. Aarons, Herbert. 1966. Abbey Press. 1964. Abbey Road Building Society. 1935. Abbott, F. Smith. 1930. Abbott, Hilda F. 1934. Abbott, William. 1897, 1929-1931, 1938, n.d. Abbott, William, Mrs. 1927. Abett, C.S. 1962. Abraham, Florence. n.d. Abrams, Alan. 1954. Abyssinia Association. 1936-1952, n.d. See also Beaufort-Palmer, Francis; Samuel, Herbert. Academie Diplomatique Internationale. 1935. Academy of Political Science. 1953. Acaland, F.A. 1929. Acaland, Richard. 1937-1939. Achilles, Theodore C. 1964. Achurch, G. Philip. 1927. See Parker, Winder, and Achurch. Ackland, G. 1937. Aclosoroff, C. (Dr.). 1930. Adams, Ernest. 1935. Adams, Leslie. 1947. Adams, M. Bridges (Mrs.). 1916. Adams, Mrs. n.d. Adamson, Vera. 1953. Addams, ?. n.d. Addams, Jane. 1932-1935. Addey, E. 1917. Addey and Stanhope School. 1935, 1950, 1959-1960, n.d. Addison, Christopher. 1930-1931, 1935. Aerofilms, Ltd. 1938. Agar, Herbert. 1941. Agar, William. 1943. Agence Litteraire Internationale. 1934-1937. Agent, Tom Nally. 1929. Agent General for India. 1942-1943. Agnew, John C. 1954-1964, n.d. Aguilera, J. de. 1950. Ahearne, Jean. 1954, n.d. Ahearne, Rosemary. 1953, 1961, n.d. Ahern, P. 1924. Ahler, C.N. 1937. Ahmed, S.M. 1942, n.d. Ahrens, E.H. 1944. Aid Refugee Chinese Intellectuals, Inc. 1952. Aid to Displaced Persons and Its European Villages. 1959. Aikenhead, Helen. 1942. Ainsworth, Felicity. 1952. Aire and Calder Navigation. 1929. Aistrop, Jack. -

A Peace Odyssey Commemorating the 100Th Anniversary of the Awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize

CALL FOR PAPERS HOFSTRA CULTURAL CENTER in cooperation with THE PEACE HISTORY SOCIETY presents 2001: A Peace Odyssey Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize AN INTERDISCIPLINARY CONFERENCE THURSDAY, FRIDAY, SATURDAY NOVEMBER 8, 9, 10, 2001 HEMPSTEAD, NEW YORK 11549 JEAN HENRI DUNANT, FRÉDÉRIC PASSY, ÉLIE RALPH BUNCHE, LÉON JOUHAUX, ALBERT SCHWEITZER, DUCOMMUN, CHARLES ALBERT GOBAT, SIR WILLIAM GEORGE CATLETT MARSHALL, THE OFFICE OF THE RANDAL CREMER, INSTITUT DE DROIT INTERNATIONAL, UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES, BARONESSPROBERTHAPACESOPHIE ETFELICITA VON SUTTNER, LESTER BOWLES PEARSON, GEORGES PIRE, PHILIP J. NÉEFCOUNTESSRATERNITATEKINSKY VON CHINIC UND TETTAU, NOEL-BAKER, ALBERT JOHN LUTULI, DAG HJALMAR THEODOREENTIUMROOSEVELT, ERNESTO TEODORO MONETA, AGNE CARL HAMMARSKJÖLD, LINUS CARL PAULING, LOUISGRENAULT, KLAS PONTUS ARNOLDSON, FREDRIK COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DE LA CROIX ROUGE, LIGUE BAJER(F, ORAUGUSTE THE PMEACEARIE FRANŸOIS AND BEERNAERT, PAUL DES SOCIÉTÉS DE LA CROIX-ROUGE, MARTIN LUTHER ROTHERHOOD OF EN HENRIB BENJAMIN BALLUET, BARONM D)E CONSTANT DE KING JR., UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN'S FUND, RENÉ REBECQUE D'ESTOURNELLE DE CONSTANT, THE CASSIN, THE INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION, PERMANENT INTERNATIONAL PEACE BUREAU, TOBIAS N ORMAN ERNEST BORLAUG, WILLY BRANDT, MICHAEL CAREL ASSER, ALFRED HERMANN FRIED, HENRY A. KISSINGER, LE DUC THO, SEÁN E LIHU ROOT, HENRI LA FONTAINE, MACBRIDE, EISAKU SATO, ANDREI COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DE LA DMITRIEVICH SAKHAROV, B ETTY CROIX ROUGE, THOMAS -

The Great Debate

The Great Debate ing that America seeks nuclear zero, Obama Is Nuclear Zero is simply reaffirming that we will follow our the Best Option? treaty commitments: states that joined the 1970 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (npt) agreed “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to Yes: Scott D. Sagan nuclear disarmament.” And since Article 6 of America’s Constitution says that a treaty com- very time Barack Obama announces mitment is “the supreme Law of the Land,” at that he is in favor of a world free of a basic level, Obama is simply saying that he E nuclear weapons, the nuclear hawks will follow U.S. law. descend. Soon after his inauguration, for- The abolition aspiration is not, however, mer–Reagan administration Pentagon of- based on such legal niceties. Instead, it is ficial Frank Gaffney proclaimed that the inspired by two important insights about the president “stands to transform the ‘world’s global nuclear future. First, the most dan- only superpower’ into a nuclear impotent.” gerous nuclear threats to the United States After Obama promised in his 2009 Prague today and on the horizon are from terrorists speech that “the United States will take con- and potential new nuclear powers, not from crete steps toward a world without nuclear our traditional Cold War adversaries in Rus- weapons,” former–Secretary of Defense James sia and China. Second, the spread of nuclear Schlesinger declared that “the notion that weapons to new states, and indirectly to ter- we can abolish nuclear weapons reflects on rorist organizations, will be made less likely a combination of American utopianism and if the United States and other nuclear-armed American parochialism.” And when the presi- nations are seen to be working in good faith dent won the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, in part toward disarmament. -

Debate on the 'Democratic Peace': a Review

DEBATE ON THE ‘D EMOCRATIC PEACE ’: A REVIEW STEVEN GEOFFREY GIESELER AMERICAN DIPLOMACY VOL . 9 NO. 1 MARCH 2004 Copyright © 2004 American Diplomacy Publishers Chapel Hill, NC www.americandiplomacy.org _________________________________________________ AMERICAN DIPLOMACY VOL . 9 NO. 1 MARCH 2004 'Democracies do not make war on each other, and the more democratic, the less violent nations are in general.' This theory of war avoidance is the subject of much peace literature published in recent years. The author provides an overview of the field and addresses the question of its continued validity in light of the war in Iraq. — Ed. "[T]he battle for minds and souls between democracies and those who hate them . is a battle that those who love freedom cannot afford to lose." INTRODUCTION The history of war is as old as history itself. 1 The annals of thought on war avoidance are nearly as ancient. At various times during our shared past, different movements and their leaders have thought they had found the key to eradicating the plague of combat between men. From the early writings of war theorists such as Thucydides 1 and Sun Tzu, 1 to Norman Angell's "great illusion" 1 and the toothless promise of Kellogg-Briand, all such hypotheses have failed the practical test of time. The war dilemma is very much still with us and in fact getting worse, for the twentieth century and the morally paradoxical utilization of technological progress brought with them the bloodiest hundred years in the annals of man. But there is hope still. Developments in human thought and governance do offer promise for the future. -

“Debate, Democracy, and the Politics of Panic: Norman Angell in the Edwardian Crisis”

“Debate, Democracy, and the Politics of Panic: Norman Angell in the Edwardian Crisis” by Ryan Anthony Joseph Vieira B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 12 July 2006 © copyright 2006 Ryan Vieira Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-23310-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-23310-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Efforts for Peace Before World War I

Illusion and Failure? Efforts for Peace before World War I HOUGH I was born in London and spent most of my childhood T and youth there, from May 1909 to July 1911 I was at a small private school in Walmer, Kent. I arrived there soon after my seventh birthday. Many memories of those distant years remain vividly with me .. One of them provides an introduction to this paper. Sometime early in 1910, I think it must have been, after an attack of whooping-cough, my father took me back to school. To look at in the train he bought for us a copy of the Strand Magazine, then a monthly journal with a wide circulation, thanks to contributions from some of the best-known story-tellers of the day. 1 Looking through the magazine, I came upon an exciting, illustrated article describing a possible sudden invasion of England by Germany. Both the text of the article and the drawings were very realistic. I can still almost see the pages. I have an even clearer remembrance of my father's dismay, when he found what I was reading, and the haste with which he took the magazine from me. This trivial incident belonged to the period of growing concern at the growth of the German Navy and its possible threat to British supremacy on the seas. War was beginning to be talked about as a dread, though hardly credible possibility. But there were also in those years serious efforts after international understanding and peace. It is about two of them that I want to speak, after this interval of seventy years. -

Nobel Prizes List from 1901

Nature and Science, 4(3), 2006, Ma, Nobel Prizes Nobel Prizes from 1901 Ma Hongbao East Lansing, Michigan, USA, Email: [email protected] The Nobel Prizes were set up by the final will of Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist, industrialist, and the inventor of dynamite on November 27, 1895 at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, which are awarding to people and organizations who have done outstanding research, invented groundbreaking techniques or equipment, or made outstanding contributions to society. The Nobel Prizes are generally awarded annually in the categories as following: 1. Chemistry, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 2. Economics, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 3. Literature, decided by the Swedish Academy 4. Peace, decided by the Norwegian Nobel Committee, appointed by the Norwegian Parliament, Stortinget 5. Physics, decided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 6. Physiology or Medicine, decided by Karolinska Institutet Nobel Prizes are widely regarded as the highest prize in the world today. As of November 2005, a total of 776 Nobel Prizes have been awarded, 758 to individuals and 18 to organizations. [Nature and Science. 2006;4(3):86- 94]. I. List of All Nobel Prize Winners (1901 – 2005): 31. Physics, Philipp Lenard 32. 1906 - Chemistry, Henri Moissan 1. 1901 - Chemistry, Jacobus H. van 't Hoff 33. Literature, Giosuè Carducci 2. Literature, Sully Prudhomme 34. Medicine, Camillo Golgi 3. Medicine, Emil von Behring 35. Medicine, Santiago Ramón y Cajal 4. Peace, Henry Dunant 36. Peace, Theodore Roosevelt 5. Peace, Frédéric Passy 37. Physics, J.J. Thomson 6. Physics, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen 38. -

Rondon, Einstein's Letter and the Nobel Peace Prize

Cienciaˆ e Sociedade, CBPF, v. 4, n. 1, p. 27-00, 2016 dx.doi.org/10.7437/CS2317-4595/2016.04.002 Rondon, Einstein’s Letter and the Nobel Peace Prize Rondon, a Carta de Einstein e o Premioˆ Nobel da Paz Marcio Luis Ferreira Nascimento∗ Institute of Humanities, Arts and Sciences, Federal University of Bahia, Rua Barao˜ de Jeremoabo s/n, Idioms Center Pavilion (PAF IV), Ondina University Campus, 40170-115 Salvador, Bahia, Brazil: www.lamav.ufba.br PROTEC / PEI — Graduate Program in Industrial Engineering, Department of Chemical Engineering, Polytechnic School, Federal University of Bahia, Rua Aristides Novis 2, Federac¸ao,˜ 40210-630 Salvador, Bahia, Brazil: www.protec.ufba.br Submetido: 2/05/2016 Aceito: 10/05/2106 Abstract: We briefly discuss a letter written by physicist of German origin Albert Einstein (1879-1955) to the Norwegian Nobel Committee nominating the Brazilian military officer, geographer, explorer and peacemaker Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon (1865-1958). Einstein nominated other eleven scientists, and all them were Nobel Prizes laureates. We also examine and discuss the Nobel Peace Prize Nominators and Nominees from 1901 to 1964. Just taking into account data up to the year of the Nobel Prize, the highest number of nom- inations was awarded to an organization, the Permanent International Peace Bureau in 1910, with a total of 103 nominations, followed by two women: Bertha von Suttner (101 nominations, 1905) and Jane Addams (91 nominations, 1931). Data show that the average number of nominations per Nobel Prize awarded was 17.7, and only 18 of the total 62 laureates exceed this average. -

Francia Bd. 40

Francia – Forschungen zur westeuropäischen Geschichte Bd. 40 2013 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online- Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung - Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Peter Farrugia FAILURE OF IMAGINATION? Rationalism, Pacifism, Memory, and the Writing of Jean de Bloch and Norman Angell (1898–1914) On July 31, 1914, with Europe teetering on the brink of war, much of the Parisian fourth estate could be found in the Café du Croissant, one of the establishments of choice among local jour- nalists. The tight knots of diners were anxiously discussing the thing on everyone’s mind: the likelihood of a European conflict. Around 9:30, heated conversations were interrupted by a se- ries of gunshots. At first, those present thought that unrest had erupted outside, in the rue Montmartre. However, it quickly became clear that the shots were intended for a specific tar- get. That target was the French socialist leader, Jean Jaurès who was assassinated by the young French nationalist, Raoul Villain. As one eyewitness put it, »[i]t is impossible to one who knew M. Jaurès [. .] to write about it calmly with the grief fresh upon one«1. Even amongst Jaurès’ political enemies, the import of the assassination was immediately rec- ognized.