Protection of Geographical Indication Under Intellectual Property Rights By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Published Under Section 4(1)(A) & (B) to Right to Information Act 2005

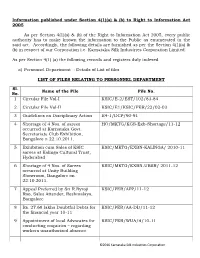

Information published under Section 4(1)(a) & (b) to Right to Information Act 2005 As per Section 4(1)(a) & (b) of the Right to Information Act 2005, every public authority has to make known the information to the Public as enumerated in the said act. Accordingly, the following details are furnished as per the Section 4(1)(a) & (b) in respect of our Corporation i.e. Karnataka Silk Industries Corporation Limited. As per Section 4(1) (a) the following records and registers duly indexed a) Personnel Department : Details of List of files LIST OF FILES RELATING TO PERSONNEL DEPARTMENT Sl. Name of the File File No. No. 1 Circular File Vol-I KSIC/E-2/EST/102/83-84 2 Circular File Vol-II KSIC/E1/KSIC/PER/22/02-03 3 Guidelines on Disciplinary Action E4-1/DCP/90-91 4 Shortage of 4 Nos. of sarees HO/MKTG/KGS-Exb-Shortage/11-12 occurred at Karnataka Govt. Secretariate Club Exhibition, Bangalore n 22.10.2011. 5 Exhibition cum Sales of KSIC KSIC/MKTG/EXBN-KALINGA/ 2010-11 sarees at Kalinga Cultural Trust, Hyderabad 6 Shortage of 4 Nos. of Sarees KSIC/MKTG/EXBN-UBSR/ 2011-12 occurred at Unity Building Showroom, Bangalore on 22.10.2011. 7 Appeal Preferred by Sri R.Byroji KSIC/PER/APP/11-12 Rao, Sales Attender, Reshmalaya, Bangalore 8 Rs. 27.68 lakhs Doubtful Debts for KSIC/PER/AA-DD/11-12 the financial year 10-11 9 Appointment of local Advocates for KSIC/PER/WUA/4/10-11 conducting enquiries – regarding workers unauthorized absence ©2016 Karnataka Silk Industries Corporation 10 Theft of 17 Nos. -

IBTEX No. 48 of 2016 March 04, 2016

IBTEX No. 48 of 2016 March 04, 2016 USD 67.29 | EUR 73.63 | GBP 95.26| JPY 0.59 Spot Prices of Overseas Ring Spun Yarn in Indicative Prices of Cotton Grey Fabrics in China Chinese Market Date: 3 Mar-2016 FOB Price Date:3 2-Mar-2016 Price (Post-Tax) (Pre-Tax) Description Prices Prices (USD/Kg.) (Domestic Production) (Yuan/Meter) Country C32Sx32S 130x70 63” 2/1 fine 20S 30S 7.20 Carded Carded twill India 2.10 2.30 C40Sx40S 133X72 63” 1/1 poplin 6.40 Indonesia 2.81 3.26 C40Sx40S 128X68 67” 2/1 twill 6.00-6.20 Pakistan 2.22 2.60 24Sx24S 72x60 54” 1/1 batik Turkey 2.60 2.80 4.60 Source CCF Group dyeing 20Sx20S 60x60 63” 1/1 plain cloth 6.20 Exhibit your company at www.texprocil.org at INR 990 per annum Please click here to register your Company’s name DISCLAIMER: The information in this message July be privileged. If you have received it by mistake please notify "the sender" by return e-mail and delete the message from "your system". Any unauthorized use or dissemination of this message in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Any "information" in this message that does not relate to "official business" shall be understood to be neither given nor endorsed by TEXPROCIL - The Cotton Textiles Export Promotion Council. Page 1 News Clippings NEWS CLIPPINGS INTERNATIONAL NEWS No Topics 1 Call to adopt BT cotton production 2 Pakistan: Govt importing 50 lac cotton bales to meet local demands 3 Hopes raised Turkey can save Nigeria textile industry 4 Cambodia Mulls Joining TPP to Boost Trade 5 Time to put the TPP out of its Misery? 6 Pakistan textile -

Use Style: Paper Title

Volume 6, Issue 7, July – 2021 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Impact of Traditional Textile on the Gross Domestic Product- GDP of Bangladesh 1*Engr. Md. Eanamul Haque Nizam, 1Sheikh Mohammad Rahat, 1*Assistant Professor. Department of Textile Engineering, 1Albert Loraence Sarker, Bangladesh University of Business and Technology 2Abhijit Kumar Asem, [BUBT], Rupnagar, Mirpur-2, Dhaka-1216, Bangladesh 2Rezwan Hossain, 3Rayek Ahmed, 3Mashrur Wasity 1,2,3Textile Graduate, Department of Textile Engineering, Bangladesh University of Business and Technology [BUBT], Rupnagar, Mirpur-2, Dhaka-1216, Bangladesh Abstract:- Bangladesh is a country loaded with share of GDP. Consultancy firm McKinsey and Company has craftsmanship, culture, and legacy. For the most part, the said Bangladesh could double its garments exports in the next specialty of attire or material is the most seasoned legacy 10 years. In Asia, Bangladesh is the one of the biggest largest that introduced the land to the external world since such exporter of textile products providing employment to a great countless years prior. Customary material is perhaps the share percent of the work force in the country [1]. Currently, main piece of its material area. Customary legacy is the textile industry accounts for 45% of all industrial covered up in each edge of Bangladesh where Jamdani, employment in the country and contributes 5% of the total Muslin, Tangail, Banarasi, Lungi, and so forth assume an national income. However, although the industry is one of the indispensable part. It is assessed that there are 64,100 largest in Bangladesh and is still expanding, it faces massive handlooms in the region. -

Expounding Design Act, 2000 in Context of Assam's Textile

EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR Dissertation submitted to National Law University, Assam in partial fulfillment for award of the degree of MASTER OF LAWS Supervised by, Submitted by, Dr. Topi Basar Anee Das Associate Professor of Law UID- SF0217002 National Law university, Assam 2nd semester Academic year- 2017-18 National Law University, Assam June, 2018 SUPERVISOR CERTIFICATE It is to certify that Miss Anee Das is pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam and has completed her dissertation titled “EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR” under my supervision. The research work is found to be original and suitable for submission. Dr. Topi Basar Date: June 30, 2018 Associate Professor of Law National Law University, Assam DECLARATION I, ANEE DAS, pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam, do hereby declare that the present Dissertation titled "EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR" is an original research work and has not been submitted, either in part or full anywhere else for any purpose, academic or otherwise, to the best of my knowledge. Dated: June 30, 2018 ANEE DAS UID- SF0217002 LLM 2017-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To succeed in my research endeavor, proper guidance has played a vital role. At the completion of the dissertation at the very onset, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research guide Dr. Topi Basar, Associate professor of Law who strengthen my knowledge in the field of Intellectual Property Rights and guided me throughout the dissertation work. -

Download Full Text

International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research ISSN: 2455-8834 Volume: 04, Issue: 04 "April 2019" GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATION IN INDIA: CURRENT SCENARIO AND THEIR PRODUCT DISTRIBUTION Swati Sharma Independent Researcher, Gohana, Distt. Sonipat, 131301. ABSTRACT Purpose- The main purpose of this paper is to discuss the concept of geographical indication in India. As geographical indication is an emerging trend and helps us to identify particular goods having special quality, reputation or features originating from a geographical territory. Research methodology- The main objective of the study is to analyze the current scenario and products registered under geographical indication in India during April 2004- March 2019 and discuss state wise, year wise and product wise distribution in India. Secondary data was used for the study and the data was collected from Geographical Indications Registry. Descriptive analysis was used for the purpose of analysis. Findings- The result of present study indicates that Karnataka has highest number of GI tagged products and maximum number of product was registered in the year 2008-09. Most popular product that is registered is handicraft. 202 handicrafts were registered till the date. Implications- The theoretical implications of the study is that it provides State wise distribution, year wise distribution and product wise distribution of GI products in India. This helps the customers as well as producers to make a brand name of that product through origin name. Originality/Value- This paper is one of its kinds which present statistical data of Geographical Indications products in India. Keywords: Geographical Indications, Products, GI tag and Place origin. INTRODUCTION Every geographical region has its own name and goodwill. -

July 2015–December 2015

ACUITAS-The Journal of Management ACUITAS The Journal of Management Research Volume VI Issue-II July 2015–December 2015 Vol VI, Issue-II, (July-December, 2015) Page 1 ACUITAS-The Journal of Management ACUITAS - The Journal of Management Research Volume VI Issue-I January 2015–June 2015 Patron: Bhadant Arya Nagarjuna Shurei Sasai Chairman, P.P. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Smarak Samiti, Deeksha Bhoomi, Nagpur Shri. S.J. Fulzele Secretary, P.P. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Smarak Samiti, Deeksha Bhoomi, Nagpur Advisory Board: Dr. Vilas Chopde, Vice-Principal, Dr. Ambedkar College, Nagpur Capt. C.M. Chitale, Dean, Faculty of management, Savitribai Phule Pune University Dr. Babanrao Taywade, Dean, Faculty of Commerce, RTM Nagpur, University, Nagpur Editorial Board: Dr. Sudhir Fulzele, Director, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Institute of Management Studies and Research, Nagpur Dr. S.G. Metre, Professor, Dr. BabasahebAmbedkar Institute of Management Studies and Research, Nagpur Dr. Charles Vincent, Professor, Centrum Catolica, Pontificia Universidad Catalica de Peru, South Africa Dr. S.S. Kaptan, Head of the Department and Research Centre, Savitribai Phule Pune University Dr. V.S. Deshpande, Professor, Department of Business Management, RTM Nagpur University, Dr. D.Y. Chacharkar, Reader, SGB Amravati University Dr. S.B. Sadar, Head of the Department, Department of Business Management, SGB Amravati University Dr. J.K. Nandi, Associate Dean, IBS, Nagpur Dr. Anil Pathak, Assistant Professor, MDI, Gurgaon Mr. Sangeet Gupta, Managing Director, Synapse World Wide, Canberra, Australia Ms. Sanchita Kumar, GM-HRD, Diffusion Engineering Ltd. Vol VI, Issue-II, (July-December, 2015) Page 2 ACUITAS-The Journal of Management Editorial Committee: Dr. Nirzar Kulkarni Executive Editor Dr. -

Journal 33.Pdf

1 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 33 APRIL 30, 2010 / VAISAKHA 2, SAKA 1932 2 INDEX Page S.No. Particulars No. 1. Official Notices 4 2. G.I Application Details 5 3. Public Notice 11 4. Sandur Lambani Embroidery 12 5. Hand Made Carpet of Bhadohi 31 6. Paithani Saree & Fabrics 43 7. Mahabaleshwar Strawberry 65 8. Hyderabad Haleem 71 9. General Information 77 10. Registration Process 81 3 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 33 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th April 2010 / Vaisakha 2, Saka 1932 has been made available to the public from 30th April 2010. 4 G.I. Geographical Indication Class Goods App.No. 1 Darjeeling Tea (word) 30 Agricultural 2 Darjeeling Tea (Logo) 30 Agricultural 3 Aranmula Kannadi 20 Handicraft 24, 25 & 4 Pochampalli Ikat Textile 27 5 Salem Fabric 24 Textile 6 Payyannur Pavithra Ring 14 Handicraft 7 Chanderi Fabric 24 Textile 8 Solapur Chaddar 24 Textile 9 Solapur Terry Towel 24 Textile 10 Kotpad Handloom fabric 24 Textile 24, 25 & 11 Mysore Silk Textile 26 12 Kota Doria 24 & 25 Textile 13 Mysore Agarbathi 3 Manufactured 14 Basmati Rice 30 Agricultural 15 Kancheepuram Silk 24 & 25 Textile 16 Bhavani Jamakkalam 24 Textile 17 Navara - The grain of Kerala 30 Agricultural 18 Mysore Agarbathi "Logo" 3 Manufactured 19 Kullu Shawl 24 Textile 20 Bidriware 6, 21 & 34 Handicraft 21 Madurai Sungudi Saree 24 & 25 -

'Development of Silk Industry, During the Rule of Princely Mysore

© 2018 IJRAR September 2018, Volume 5, Issue 3 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) ‘Development of Silk Industry, During the Rule of Princely Mysore State (1866-1947)’-- A Study Rekha HG Assistant Professor of History Government First Grade College Vijayanagar, Bangalore Abstract The Mysore Silk is synonymous with splendour and grandeur of Royal Mysore State. Mysore silk has been registered as Geographical Indicator under Intellectual Property Rights. Mysore state is the homeland of Mysore Silk has a history of more than 215yrs .By the turn of nineteenth century; Mysore was poised to take off into the skies of progress and development. In the industrial advancement of the country measured by its turn sericulture next to agriculture was the most important industry carried on in the Mysore state. Present study focus on the development of silk industry in Mysore State., Credit of introducing the Sericulture in Mysore state goes to Tippu Sultan, were Tippu sent delegation to South China to collect seed for silk farming. , Mysore State had set a noble example because of energetic initiative by Maharajas and Dewans, and also Mysore enjoyed certain natural facilities and mineral resources, which have been exploited with a foresight worthy of all sorts. Delegates of Italian and Japanese sericulturists played the crucial role in the development of silk industry. Factories and filatures were set up, good texture of silk were worn. World economic depression had a competition from imported silk and during the second half of the 20th century it was revived and Mysore State become the top multivoltine silk producer in India. -

Journal 45.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 45 September 11, 2012 / BHADRA 20, SAKA 1933 INDEX S.No. Particulars Page No. 1. Official Notices 4 2. New G.I Application Details 5 3. Public Notice 6 4. GI Applications Bhagalpur Silk Fabrics & Sarees – GI Application No. 180 7 Mangalagiri Sarees and Fabrics– GI Application No. 198 Madurai Malli – GI Application No. 238 Tequila – GI Application No. 243 5. General Information 6. Registration Process OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 45 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 11th September 2012 / Bhadra 20th, Saka 1933 has been made available to the public from 11th September 2012. NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS 371 Shaphee Lanphee 25 Manufactured 372 Wangkhei Phee 25 Manufactured 373 Moirang Pheejin 25 Manufactured 374 Naga Tree Tomato 31 Agricultural 375 Arunachal Orange 31 Agricultural 376 Sikkim Large Cardamom 30 Agricultural 377 Mizo Chilli 30 Agricultural 378 Jhabua Kadaknath Black Chicken Meat 29 Manufactured 379 Devgad Alphonso Mango 31 Agricultural 380 RajKot Patola 24 Handicraft 381 Kangra Paintings 16 Handicraft 382 Joynagarer Moa 30 Food Stuff 383 Kullu Shawl (Logo) 24 Textile 23, 24, 384 Muga Silk of Assam (Logo) 25, 27 & Handicraft 31 385 Nagpur Orange 31 Agricultural PUBLIC NOTICE No.GIR/CG/JNL/2010 Dated 26th February, 2010 WHEREAS Rule 38(2) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Rules, 2002 provides as follows: “The Registrar may after notification in the Journal put the published Geographical Indications Journal on the internet, website or any other electronic media.” Now therefore, with effect from 1st April, 2010, The Geographical Indications Journal will be Published and hosted in the IPO official website www.ipindia.nic.in free of charge. -

Haute Designers, Master Weavers

TREND WATCH LFW Summer Resort ‘16 HAUTE DESIGNERS, MASTER WEAVERS Lakme Fashion Week has set a benchmark for Indian designers. MEHER CASTELINO reports on the highlights. ASIF SHAIKH GAURANG MAKU INDIGENE BANERJEE PAROMITA FIBRE2FASHION he fabulous Walking Hand in Hand – The Craft + Design + TSociety show was one of the highlights of the first day at Lakmé Fashion Week Summer/Resort 2016. The innovative presentation featured India’s five top designers who teamed up with the best craftspersons and expert weavers. They displayed creations that combined designer and craft skills. Day Two was devoted to Sustainable and Indian Textiles. Designers presented interesting collections, showcasing textiles and crafts and also upcycling and recycling fabrics. The message was clear: fashion can be sustainable. Chikankari came Giving kinkhab The glory of the alive on the ramp under his amazing touches, leheriya was brought the creative guidance Rajesh Pratap Singh centre stage by of Aneeth Arora. worked with master Anupama Bose’s skills Master craftsman weaver Haseem and Islammuddin Jakir Hussain Mondol Muhammad for a Neelgar’s expertise. worked his magic on striking collection of The gorgeous leheriya the pretty summer formal westernwear. designs in rainbow dresses, cool blouses, Using rich, golden hues were turned into layered minis, softly brocade with floral stunning ensembles. embroidered long- weaves, Singh A ravishing red kaftan, sleeved covers, presented culottes with a feminine green/ delicately embellished cropped tops, bias cut blue gown, an electric midis, skirts and gowns jackets, dhoti pants, anarkali, a variety of in shades of white and capris, coat dresses, sarees in leheriya and pale blue/grey. -

Muga Silk Rearers: a Field Study of Lakhimpur District of Assam

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 04, APRIL 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Muga Silk Rearers: A Field Study Of Lakhimpur District Of Assam Bharat Bonia Abstract: Assam the centre of North- East India is a highly fascinated state with play to with biodiversity and wealth of natural resource. Lakhimpur is an administrative district in the state of Assam, India. Its headquarter is North Lakhimpur. Lakhimpur district is surrounded by North by Siang and Papumpare district of Arunachal Pradesh and on the East by Dhemaji District and Subansiri River. The geographical location of the district is 26.48’ and 27.53’ Northern latitude and 93.42’ and 94.20' East longitude (approx.). Their existence of rare variety of insects and plants, orchids along various wild animals, birds. And the rest of the jungle and sanctuaries of Assam exerts a great contribution to deliberation of human civilization s. Among all these a peculiar kind of silkworm “Mua” sensitive by nature, rare and valuable living species that makes immense impact on the economy of the state of Assam and Lakhimpur district and paving the way for the muga industry. A Muga silkworm plays an important role in Assamsese society and culture. It also has immense impacts on Assams economy and also have an economic impacts on the people of Lakhimpur district which are specially related with muga rearing activities. Decades are passes away; the demand of Muga is increasing day by day not only in Assam but also in other countries. But the ratio of muga silk production and its demand are disproportionate. -

EXPRESSION of INTEREST for TESTING of SAMPLES.Pdf

EXPRESSION OF INTEREST FOR TESTING OF SAMPLES UNDER INDIA HANDLOOM BRAND Government of India Ministry of Textiles Office of the Development Commissioner for Handlooms Udyog Bhawan, New Delhi-110 011 Tel : 91-11-2306-3684/2945 Fax: 91-11-2306-2429 1. Introduction 1.1 India Handloom Brand (IHB) has been launched by the Govt. of India to endorse the quality of the handloom products in terms of raw material, processing, embellishments, weaving, design and other parameters besides social and environmental compliances. The IHB is given only to high quality defect free product to cater to the needs of those customers who are looking for niche handmade products. 1.2 The list of products eligible for registration under the IHB is enclosed at Annexure – 1(A). However, as per recommendation of IHB Review Committee, new items can be included/ existing specifications can be changed/ new specifications may be added in the list from time to time. 1.3 For registration under IHB, the applicant has to submit on-line application in the website www.indiahandloombrand.gov.in. The applicant has to then submit the printout of the online application form and the sample of the product of atleast 0.25 mt. length in full width to the concerned Weavers’ Service Centre (WSC). The applicant also has to submit registration fee of Rs. 500 plus service taxes in the form of Demand Draft or through on-line payment. The WSCs will then send the sample to the testing laboratory for testing. 1.4 The sample received by the laboratory has to be tested as per standard testing procedure and testing result has to be submitted before Evaluation Committee in the Evaluation committee meeting which is generally held in Textiles Committee, Mumbai.