Darwin, Eliot, Stevenson and the Lamarckian Legacy of 1820S Edinburgh Patrick G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Article Full Text PDF (646KB)

BOOK REVIEWS ism was condemned by a Friend in "his denunciation of the Church's 'adulterous connection' with the state." He "abominated the 'fornicating' Church, indicting it for the The Politics of Evolution: Morphology, Medicine, 'filthy crime of adultery' with aristocratic government, and Reform in Radical London. Adrian Desmond. which had left it with the 'stigma of disgrace' to degenerate 1989. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. into 'an inflictor of misery... a destroyer of moral principle 503 p. $34.95 cloth. ... a subverter of the good order of society.'" Desmond focuses our attention midway between the In a counterattack, the conservative scientists avowed French Revolution and the appearance of Darwin's Origin "that the new crop of foul fruits being harvested in Britain, of Species, the score of years around 1830. He describes the treason, blasphemy, and riots, was the result of a diseased political, social, and scientific ferment in radical London 'speculative science' spawned by the French Revolution." that fueled an evolving appreciation of natural law rather The radicals were accused of "inciting the working classes." than divine creation to explain the what, when, why, and There were to be "fatal consequences of an atheistic self- how of the living world. Signs of its emergence appeared developing nature for the authority of kings and priests." "when the first wave of Scottish students arrived in Paris The Radicals as physiologists "explained higher organic after Waterloo" around 1820 where "they found Jean- wholes by their physico-chemical constituents, while as Baptiste Lamarck, at seventy-one, tetchy, pessimistic, and democrats they saw political constituents, voters, em- losing his sight." A more liberal medical education was powered to sanction a higher authority: a delegate to act available in Roman Catholic France than in Calvinistic in their interest." Organisms derived their existence by Scotland. -

The Historiography of Archaeology and Canon Greenwell

The Historiography of Archaeology and Canon Greenwell Tim Murray ([email protected]) In this paper I will focus the bulk of my remarks on setting studies of Canon Greenwell in two broader contexts. The first of these comprises the general issues raised by research into the historiography of archaeology, which I will exemplify through reference to research and writing I have been doing on a new book A History of Prehistoric Archaeology in England, and a new single-volume history of archaeology Milestones in Archaeology, which is due to be completed this year. The second, somewhat narrower context, has to do with situating Greenwell within the discourse of mid-to-late 19th century race theory, an aspect of the history of archaeology that has yet to attract the attention it deserves from archaeologists and historians of anthropology (but see e.g. Morse 2005). Discussing both of these broader contexts will, I hope, help us address and answer questions about the value of the history of archaeology (and of research into the histories of archaeologists), and the links between these histories and a broader project of understanding the changing relationships between archaeology and its cognate disciplines such as anthropology and history. My comments about the historiography of archaeology are in part a reaction to developments that have occurred over the last decade within archaeology, but in larger part a consequence of my own interest in the field. Of course the history of archaeology is not the sole preserve of archaeologists, and it is one of the most encouraging signs that historians of science, and especially historians writing essentially popular works (usually biographies), have paid growing attention to archaeology and its practitioners. -

A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ASketchoftheLifeandWritingsRobertKnox,Anatomist HenryLonsdale V ROBERT KNOX. t Zs 2>. CS^jC<^7s><7 A SKETCH LIFE AND WRITINGS ROBERT KNOX THE ANA TOM/ST. His Pupil and Colleague, HENRY LONSDALE. ITmtfora : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1870. / *All Rights reserve'*.] LONDON : R. CLAV, SONS, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. TO SIR WILLIAM FERGUSSON, Bart. F.R.S., SERJEANT-SURGEON TO THE QUEEN, AND PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS OF ENGLAND. MY DEAR FERGUSSON, I have very sincere pleasure in dedicating this volume to you, the favoured pupil, the zealous colleague, and attached friend of Dr. Robert Knox. In associating your excellent name with this Biography, I do honour to the memory of our Anatomical Teacher. I also gladly avail myself of this opportunity of paying a grateful tribute to our long and cordial friendship. Heartily rejoicing in your well-merited position as one of the leading representatives of British Surgery, I am, Ever yours faithfully, HENRY LONSDALE. Rose Hill, Carlisle, September 15, 1870. PREFACE. Shortly after the decease of Dr. Robert Knox (Dec. 1862), several friends solicited me to write his Life, but I respectfully declined, on the grounds that I had no literary experience, and that there were other pupils and associates of the Anatomist senior to myself, and much more competent to undertake his biography : moreover, I was borne down at the time by a domestic sorrow so trying that the seven years since elapsing have not entirely effaced its influence. -

Valuing Race? Stretched Marxism and the Logic of Imperialism

Valuing race? Stretched Marxism and the logic of imperialism Robert Knox* This article attempts to demonstrate the intimate interconnection between Downloaded from value and race in international law. It begins with an exploration of Marxist understandings of imperialism, arguing that they falsely counterpose race and value. It then attempts to reconstruct an account in which the two are under- stood as mutually constitutive. http://lril.oxfordjournals.org/ THE HAITIAN INTERVENTION—VALUE, LAW AND RACE? In his 2008 article ‘Multilateralism as Terror: International Law, Haiti and Imperialism’,1 China Mie´ville dissects the 2004 UN intervention in Haiti. In February 2004, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, leader of the leftwing Fanmi Lavalas movement, was overthrown. Boniface Alexandre, Supreme Court Chief at University of Liverpool on March 22, 2016 Justice, was appointed interim-President, and requested international support. In response, the Security Council passed Resolution 1529, which expressed deep concern for ‘the deterioration of the political, security and humanitarian situ- ation’. Acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, the Security Council authorised a multinational ‘peacekeeping force’ which could ‘take all necessary measures’ to ‘support the constitutional process under way in Haiti’ and ‘maintain public safety and law and order and to protect human rights’. Pursuant to the Resolution, the United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) was created. * Lecturer, School of Law and Social Justice, University of Liverpool. Email: [email protected]. I would like to thank Tor Krever and Anne Neylon for their incisive comments on drafts of this article, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their very extensive feedback. -

Designing the Dinosaur: Richard Owen's Response to Robert Edmond Grant Author(S): Adrian J

Designing the Dinosaur: Richard Owen's Response to Robert Edmond Grant Author(s): Adrian J. Desmond Source: Isis, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Jun., 1979), pp. 224-234 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/230789 . Accessed: 16/10/2013 13:00 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 150.135.115.18 on Wed, 16 Oct 2013 13:00:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Designing the Dinosaur: Richard Owen's Response to Robert Edmond Grant By Adrian J. Desmond* I N THEIR PAPER on "The Earliest Discoveries of Dinosaurs" Justin Delair and William Sarjeant permit Richard Owen to step in at the last moment and cap two decades of frenzied fossil collecting with the word "dinosaur."' This approach, I believe, denies Owen's real achievement while leaving a less than fair impression of the creative aspect of science. -

Observation and ``Science'' in British Anthropology Before

Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences xxx (2015) 1e3 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc Essay review Observation and “Science” in British anthropology before the “Malinowskian Revolution” George Baca College of International Studies, Dong-A University, Busan, South Korea When citing this paper, please use the full journal title Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences The Making of British Anthropology, 1813e1871, Efram Sera- technically an enemy of the British state. He dodged British Shriar. Pickering and Chatto, London (2013). pp. 272, Price £60/ detention centers for a two-year field trip in the Trobriand Islands. $99 hardcover, ISBN: 978 1 84893 394 1 With the arduous travails of fieldwork, learning the Trobriand language fluently, and attaining a comprehensive understanding of native social categories and beliefs, Malinowski returned Cultural and social anthropology present a curious case in in- triumphantly to the London School of Economics where he spent tellectual history. Early twentieth century reformers, of the likes of the next thirty years extolling the “secret” of social anthropolog- Franz Boas, Bronislaw Malinowski, and even Emile Durkheim, ical research (Kayberry, 1957; Leach, 1961). With the publication of helped forge a “modern” and “professional” image of anthropology the Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), he crafted a viable through wholesale attacks on many of the discipline’s founding mythology of a new discipline that had risen from the ashes of figures. On both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, these novel approaches Social Darwinism and the theoretical shortcomings of Boasian to the study of anthropology dismantled the scientific status of anthropology (Stocking, 1992). -

Presidential Address Commemorating Darwin

Presidential Address Commemorating Darwin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Browne, Janet. 2005. Presidential address commemorating Darwin. The British Journal for the History of Science 38, no. 3: 251-274. Published Version 10.1017/S0007087405006977 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3345924 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA BJHS 38(3): 251–274, September 2005. f British Society for the History of Science doi:10.1017/S0007087405006977 Presidential address Commemorating Darwin JANET BROWNE* Abstract. This text draws attention to former ideologies of the scientific hero in order to explore the leading features of Charles Darwin’s fame, both during his lifetime and beyond. Emphasis is laid on the material record of celebrity, including popular mementoes, statues and visual images. Darwin’s funeral in Westminster Abbey and the main commemorations and centenary celebrations, as well as the opening of Down House as a museum in 1929, are discussed and the changing agendas behind each event outlined. It is proposed that common- place assumptions about Darwin’s commitment to evidence, his impartiality and hard work contributed substantially to his rise to celebrity in the emerging domain of professional science in Britain. During the last decade a growing number of historians have begun to look again at the phenomena of scientific commemoration and the cultural processes that may be involved when scientists are transformed into international icons. -

Janet Browne

Janet Browne 1. Personal details Janet Elizabeth Bell Browne History of Science Department Harvard University Science Center 371 1 Oxford Street Cambridge MA 02138, USA Tel: 001-617-495-3550 Email: [email protected] 2. Education and degrees B.A.(Mod) Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, 1972. M.Sc. History of Science, Imperial College, London, 1973. Ph.D. History of Science, Imperial College, London, 1978, “Charles Darwin and Joseph Dalton Hooker: studies in the history of biogeography”. (Keddey-Fletcher Warr Scholarship of the University of London, 1975-78; British Academy 3 year PhD studentship) MA (Hon) Harvard University, 2006 Honorary DSc Trinity College Dublin, 2009 3. Professional History 1978--79, Visiting researcher, History of Science Department, Harvard University. 1979--80, Wellcome Fellow, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London. 1980--83, Research Assistant (3 year staff appointment), Wellcome Institute/ University College, London. 1983--91, Associate Editor of Correspondence of Charles Darwin and Senior Research Associate, Cambridge University Library (1990--91). 1983--93, Part-time Lecturer, MSc History of Science, UCL/Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London. 1 1993, Lecturer in History of Biology, Wellcome Centre for the History of Medicine, London. 1996, Reader in History of Biology, University College London. 1996-7, Senior Visiting Research Fellow King’s College Cambridge (stipendiary, by open competition). 2002, Professor in the History of Biology, University College London. 2006- present Aramont Professor in the History of Science, Harvard University 2008- 12 Senior Research Editor USA, Darwin Correspondence Project 2009-14 Harvard College Professor (for excellence in undergraduate teaching) 2009 Assistant chair, Department History of Science, Harvard University, 2010- Chair, Department History of Science, Harvard University 4. -

Foreign Bodies

Chapter One Climate to Crania: science and the racialization of human difference Bronwen Douglas In letters written to a friend in 1790 and 1791, the young, German-trained French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) took vigorous humanist exception to recent ©stupid© German claims about the supposedly innate deficiencies of ©the negro©.1 It was ©ridiculous©, he expostulated, to explain the ©intellectual faculties© in terms of differences in the anatomy of the brain and the nerves; and it was immoral to justify slavery on the grounds that Negroes were ©less intelligent© when their ©imbecility© was likely to be due to ©lack of civilization and we have given them our vices©. Cuvier©s judgment drew heavily on personal experience: his own African servant was ©intelligent©, freedom-loving, disciplined, literate, ©never drunk©, and always good-humoured. Skin colour, he argued, was a product of relative exposure to sunlight.2 A decade later, however, Cuvier (1978:173-4) was ©no longer in doubt© that the ©races of the human species© were characterized by systematic anatomical differences which probably determined their ©moral and intellectual faculties©; moreover, ©experience© seemed to confirm the racial nexus between mental ©perfection© and physical ©beauty©. The intellectual somersault of this renowned savant epitomizes the theme of this chapter which sets a broad scene for the volume as a whole. From a brief semantic history of ©race© in several western European languages, I trace the genesis of the modernist biological conception of the term and its normalization by comparative anatomists, geographers, naturalists, and anthropologists between 1750 and 1880. The chapter title Ð ©climate to crania© Ð and the introductory anecdote condense a major discursive shift associated with the altered meaning of race: the metamorphosis of prevailing Enlightenment ideas about externally induced variation within an essentially similar humanity into a science of race that reified human difference as permanent, hereditary, and innately somatic. -

The Darwin Industry H

Ubs 0 THE DARWIN INDUSTRY H MAURAC. FLANNERY,DEPARTMENT EDITOR 0 0- I 'vejust finished reading CharlesDarwin: The Power these circumstances,it's not surprising that it doesn't Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/68/3/163/53566/4451956.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 of Place, the second volume of Janet Browne's (2002) have the depth of Browne'swork. 0 biography of Darwin, and what strikes me is how There were seven years between the publication of Browne manages to make his story fresh and gripping the two volumes, and the intense researchBrowne did even though the basic facts are well-known, at least to is evident. For example, she gives a thorough descrip- biologists. I had heard raves about the first volume, tion of the reviews of Originof Species(1859) after its CharlesDarwin: Voyaging(1995), but I put off readingit publication.There were over 300 of them, so this is not for a long time, because like its successor, it is well over an insignificant task. Also, she puts these articles into 500 pages long. Did I really want to devote that much the context of Victorianpublication trends. The reviews Ii time and brain power, even to Darwin?After all, I had were numerous because there was obviously great read Adrian Desmond and James Moore's (1991) interest in the book, but also because there had been a Darwin. Admittedly,it was a one-volumebiography, but proliferationof journals at this time due to improve- it did run to more than 700 pages. -

G Iant Snakes

Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes Giant Giant Snakes A Natural History John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield Snakes, particularly venomous snakes and exceptionally large constricting snakes, have haunted the human brain for a millennium. They appear to be responsible for our excellent vision, as well as the John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield & Tom C. Murphy John anxiety we feel. Despite the dangers we faced in prehistory, snakes now hold clues to solving some of humankind’s most debilitating diseases. Pythons and boas are capable of eating prey that is equal to more than their body weight, and their adaptations for this are providing insight into diabetes. Fascination with snakes has also drawn many to keep them as pets, including the largest species. Their popularity in the pet trade has led to these large constrictors inhabiting southern Florida. This book explores what we know about the largest snakes, how they are kept in captivity, and how they have managed to traverse ocean barriers with our help. Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes A Natural History John C. Murphy & Tom Crutchfield Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. Giant Snakes Copyright © 2019 by John C. Murphy & Tom Cructhfield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America First Printing March 2019 ISBN 978-1-64516-232-2 Paperback ISBN 978-1-64516-233-9 Hardcover Published by: Book Services www.BookServices.us ii Copyrighted Material Some pages are omitted from this book preview. -

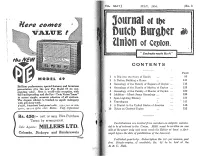

Brilliant Performance, Special Features and Luxurious Presentation Give The

VOL. 'jyGIV] JULY, 1954. INo. 3 PAGE 1 A Dip into the Story of Kandy 95 2 A Nation Building a Home 111 3 Genealogy of the Family of Bogaars of Ceylon 118 Brilliant performance, special features and luxurious 4 Genealogy of the Family of Mottau of Ceylon 123 presentation give the new Pye Model .69 its out standing value. Here is world-wide reception, with 5 Genealogy of the Family of Honter of Ceylon 130 full bandspreading and the Pye "Twin Vision Tuner" 6 Addition—-Albert Jansz Genealogy ... 136 to ensure simple, accurate selection of all stations. 7 Spot-Lighting History 137 The elegant cabinet is finished in sapele mahogany with gilt facia-work. 8 Travelogues .1. " 141 6-valve, 8-n>aveband bandspread radio, IOO-IJOV. or 200- 9 A Diarist in the United States of America 146 '2fov., 40-100 cycles A.C. Mains. Fully tropkalised. 10 Notes on Current Topics 152 Contributions are invited from members on subjects calcula ted to be of interest to the Union. MSS. must be written on one side of the paper only and must reach the Editor at least a fort night before the date of publication of the Journal. Published quarterly. Subscription Ms. 10/- per annum, post free. Single \copies, if available, Es. 5J- to be had at the D. B. U. Hall. Journal of the ' - ■ - The objects of the Union shall be : Dutch Burgher Onion of Ceylon. To promote the moral, intellectual, and social well- VOL. XLIV.] JULY, 1954, ' ■ [No. 3 being of the Dutch descendants in Ceylon.