Station to Station Project, and How of the Need for a Different Template for Culture to Did It Come About? Exist In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Formats

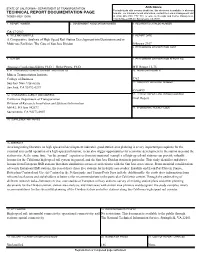

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE formats. For alternate format information, contact the Forms Management Unit TR0003 (REV 10/98) at (916) 445-1233, TTY 711, or write to Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA-17-2969 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE A Comparative Analysis of High Speed Rail Station Development into Destination and/or Multi-use Facilities: The Case of San Jose Diridon February 2017 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris Ph.D. / Deike Peters, Ph.D. MTI Report 12-75 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER Mineta Transportation Institute College of Business 3762 San José State University 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER San José, CA 95192-0219 65A0499 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Report Division of Research, Innovation and Systems Information MS-42, PO Box 942873 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE Sacramento, CA 94273-0001 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT As a burgeoning literature on high-speed rail development indicates, good station-area planning is a very important prerequisite for the eventual successful operation of a high-speed rail station; it can also trigger opportunities for economic development in the station area and the station-city. At the same time, “on the ground” experiences from international examples of high-speed rail stations can provide valuable lessons for the California high-speed rail system in general, and the San Jose Diridon station in particular. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Making West Norwood & Tulse Hill Better for Business

STATION TO STATION: MAKING WEST NORWOOD & TULSE HILL BETTER FOR BUSINESS OUR PLANS TO CREATE A BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT www.stationtostation.london 1 STATION TO STATION IS FOR INTRODUCTION ALL BUSINESSES WHO WANT Dear Friends, TO PROSPER IN A GROWING, I hope you feel as privileged as I do to work in one of the most up-and-coming parts of this great city of ours – West Norwood VIBRANT PLACE & Tulse Hill. I am always finding new ‘hidden gems’ here. “I’m really pleased Since I arrived as manager of Parkhall in 2014, the that the businesses in neighbourhood has seen massive improvements, with a new West Norwood & Tulse Hill are Leisure Centre, upgraded pavements and street furniture, the getting an opportunity to come together. BIDs elsewhere in Lambeth have always-improving Feast and an array of exciting new shops, proven very successful and have brought in bars, cafés and restaurants. extra police officers and new apprenticeships, as well as making their neighbourhoods cleaner I am proud to chair Station to Station – the proposed new and greener. Station to Station BID will help Business Improvement District (BID) for West Norwood & create a thriving business community in West Tulse Hill. By bringing local businesses together, it aims to Norwood & Tulse Hill” take the area to another level. We believe it will make owners, Cllr Jack Hopkins, Cabinet Member customers, staff and clients happier and attract new ones. for Regeneration, Business and Culture, London Borough In the pages that follow you will read about all the exciting of Lambeth. things that Station to Station BID plans to do. -

The Age of Bowie 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE AGE OF BOWIE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Morley | 9781501151170 | | | | | The Age of Bowie 1st edition PDF Book His new manager, Ralph Horton, later instrumental in his transition to solo artist soon witnessed Bowie's move to yet another group, the Buzz, yielding the singer's fifth unsuccessful single release, " Do Anything You Say ". Now, Morley has published his personal account of the life, musical influence and cultural impact of his teenage hero, exploring Bowie's constant reinvention of himself and his music over a period of five extraordinarily innovative decades. I think Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After completing Low and "Heroes" , Bowie spent much of on the Isolar II world tour , bringing the music of the first two Berlin Trilogy albums to almost a million people during 70 concerts in 12 countries. Matthew McConaughey immediately knew wife Camila was 'something special'. Did I learn anything new? Reuse this content. Studying avant- garde theatre and mime under Lindsay Kemp, he was given the role of Cloud in Kemp's theatrical production Pierrot in Turquoise later made into the television film The Looking Glass Murders. Hachette UK. Time Warner. Retrieved 4 October About The Book. The line-up was completed by Tony and Hunt Sales , whom Bowie had known since the late s for their contribution, on bass and drums respectively, to Iggy Pop's album Lust for Life. The Sydney Morning Herald. Morely overwrites, taking a significant chunk of the book's opening to beat Bowie's death to death, the takes the next three-quarters of the book to get us through the mid-Sixties to the end of the Seventies, then a ridiculously few yet somehow still overwritten pages to blast through the Eighties, Nineties, and right up to Blackstar and around to his death again. -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

Aitken Full CV

DOUG AITKEN BORN 1968 Born in Redondo Beach, CA EDUCATION 1987-91 Art Center College of Design, BFA, Pasadena, CA 1986-87 Marymount College, Palos Verdes, CA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Return to the Real, Victoria Miro Gallery, London UK NEW ERA, Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis Sonic Mountain (Sonoma), The Donum Estate, Sonoma, CA New Horizon: Art and the Landscape, The Trustees of Reservations’ Public Art Initiative, Various Locations in Massachusetts including Martha’s Vineyard, Greater Boston, and the Berkshires Doug Aitken, Faurschou Foundation, Beijing, China Doug Aitken, Don’t Forget to Breathe, 6775 Santa Monica Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA Doug Aitken, Mirage Gstaad, Elevation 1049: Frequencies, Gstaad, Switzerland 2018 Mirage Detroit, State Savings Bank, Detroit, MI Doug Aitken, Copenhagen Contemporary, Copenhagen, Denmark Doug Aitken, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, Switzerland New Era, 303 Gallery, New York, NY Doug Aitken, Massimo De Carlo, Hong Kong, China 2017 Doug Aitken: Electric Earth, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, TX Mirage, Desert X, Palm Springs, CA migration (empire), Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN 2016 Doug Aitken, Underwater Pavilions, Parley for the Oceans and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Pacific Ocean near Catalina Island, CA Doug Aitken: Electric Earth, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA Doug Aitken: twilight, Peder Lund, Oslo, Norway 2015 Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany Victoria Miro Gallery, London, -

PRESS RELEASE Doug Aitken Opens Multiple Projects Across Europe This Summer

PRESS RELEASE Wednesday 25 March 2015 Doug Aitken opens multiple projects across Europe this summer Victoria Miro is delighted to announce a solo exhibition by Doug Aitken at the Mayfair gallery opening on 12 June. This summer marks a significant moment in the American artist’s career with two important European institutions celebrating his work: Station to Station opens at London’s Barbican on 27 June and a major survey exhibition opens at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt on 9 July. Victoria Miro Mayfair 12 June – 31 July 2015 This specific constellation of five key works has been conceived for the gallery by Doug Aitken and deals with contemporary ideas of time through the use of sound, touch, light and reflectivity, with each work existing in a zone between abstraction and representation. At the core of the exhibition is Eyes closed, wide awake (Sonic Fountain II), 2014, a free-standing sonic sculpture which combines water and sound to create an optical and auditory experience. Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt 9 July – 27 September 2015 With four expansive film installations and correlating sculptures as well as a site-specific sound installation, this major survey exhibition in Germany will present an overview of the internationally renowned artist’s heterogeneous oeuvre throughout the entire exhibition area of the Schirn – and beyond. The exhibition will be curated by Matthias Ulrich. Station to Station: A 30 Day Happening, Barbican 27 June – 26 July 2015 The Barbican stages the only international stop of Station to Station, Doug Aitken’s experiment in spontaneous artistic creation. A ‘living exhibition’ encouraging cross-disciplinary collaborations among artists from different backgrounds, Station to Station takes over the Barbican’s indoor and outdoor spaces for 30 days, drawing together an inspiring and diverse fusion of international and UK- based artists from the world of contemporary art, music, dance, graphic design and film – much of it created live in the space. -

Virtual and Physical Environments in the Work of Pipilotti Rist, Doug Aitken, and Olafur Eliasson

Virtual and Physical Environments in the work of Pipilotti Rist, Doug Aitken, and Olafur Eliasson A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ART in the Art History Program of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning April 2012 by Ashton Tucker B.A., Bowling Green State University College of Arts and Sciences Committee Chair: Morgan Thomas, Ph.D. Reader: Kimberly Paice, Ph.D. Reader: Jessica Flores, M.A. ABSTRACT The common concerns of artists Pipilotti Rist (b. 1962), Doug Aitken (b. 1968), and Olafur Eliasson (b. 1967) are symptomatic of key questions in contemporary art and culture. In this study, I examine key works by each artist, emphasizing their common interest in the interplay of virtual space and physical space and, more generally, their use of screen aesthetics. Their focus on the creative interplay of virtuality and physicality is indicative of their understanding of the fragility and uncertainty of physical perception in a world dominated by screen-based communication. In chapter one, I explore Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) and argue that the artist creates work where screen based projection and installation are interrelated elements due to her interest in creating spaces that engage the viewer both physically and virtually. In chapter two, I discuss Doug Aitken’s work and argue that he democratizes the viewing experience in a more radical way than Pipilotti Rist. In the final chapter, I discuss the work of Olafur Eliasson as it relates to California Light and Space art and the phenomenological aspects of the eighteenth-century phantasmagoria. -

Doug Aitken: Migration (Empire) a Riley Contemporary Artists Project Gallery Exhibition

N E W S R E L E A S E 2200 Dodge Street, Omaha, Nebraska 68102 Phone: 402-342-3300 Fax: 402-342-2376 www.joslyn.org For Immediate Release Contact: Amy Rummel, Director of Marketing and Public Relations June 1, 2016 (402) 661-3822 or [email protected] Doug Aitken: migration (empire) A Riley Contemporary Artists Project Gallery Exhibition Opens June 4 at Joslyn Art Museum (Omaha, NE) – Doug Aitken’s migration (empire), 2008, addresses the problematic question of what happens when human and animal worlds collide. In this video, shot on location in motel rooms across the United States, animals are removed from their natural habitats and placed in environments built for the purpose of human mobility. The latest exhibition in Joslyn Art Museum’s Riley Contemporary Artists Project Gallery, migration (empire) opens Saturday, June 4, and continues through September 5. The exhibition is included in free general Museum admission. migration (empire) finds moments of humor, but the overall tone is somber and unnerving. These animals have not only been contained but are being subjected to the same monotony to which humans willingly accede. -more- add 1-1-1-1 Doug Aitken: migration (empire) at Joslyn Art Museum As Aitken’s surrealist vignettes unfurl over the course of twenty-four minutes, the animals quickly revert to their natural instincts: a beaver finds its way to the cascade of running water in the bathtub; an unruly bison topples furniture with its massive head; a cougar tears the bed apart. In an especially poignant moment, a horse seems to watch his wild counterparts canter gracefully across the landscape on a television screen. -

Magazin 06-2003

2 Oldie Markt 06/03 Plattenbörsen Oldie Markt 06/03 3 Plattenbörsen 2003 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. Steigende Besucherzahlen zeigen, daß sie längst nicht mehr nur Tummelplatz für Insider sind. Neben teu- ren Raritäten bieten die Händler günstige Second-Hand-Platten, Fachzeitschriften, Bücher, Lexika, Poster und Zubehör an. Rund 250 Börsen finden pro Jahr allein in der Bundesrepublik statt. Oldie-Markt veröffentlicht als einzige deutsche Zeit- schrift monatlich den aktuellen Börsen- kalender. Folgende Termine wurden von den Veranstaltern bekanntgegeben: Datum Stadt/Land Veranstaltungs-Ort Veranstalter / Telefon 1. Juni Hildesheim Uni Mensa WIR (051 75) 93 23 59 1. Juni Düsseldorf WBZ am Hauptbahnhof ReRo (02 34) 30 15 60 1. Juni Passau Nibelungenhalle Marylyn Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 1. Juni Graz/Österreich Kolpinghaus Discpoint (00 43) 19 67 75 50 14. Juni Karlsruhe Badnerlandhalle Neureut Ludwig Reichmann (01 79) 697 43 12 15. Juni Braunschweig Stadthalle Maxx pro (053 37) 94 85 31 15. Juni Augsburg FC-Sportheim Haunstetten Peter Pulz (082 31) 41 42 25. Juni Rotterdam/Holland Ahoy ARC (00 31) 229 21 38 91 26. Juni Berlin Statthaus Böcklerpark Kurt Wehrs (030) 425 03 00 29. Juni Dortmund Westfalenhalle Goldsaal Manfred Peters (02 31) 48 19 39 29. Juni Linz/Österreich Volkshaus Bindermichl Marylyn Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 Die Veröffentlichung von Veranstaltungshinweisen auf Schallplattenbörsen ist eine kostenlose Service-Leistung von Oldie-Markt. Ein Anspruch auf Veröffentlichung in obenstehendem Kalender besteht nicht. 2 Oldie Markt 06/03 News Oldie Markt 06/03 3 News • News • News • News • News • News • News * Radiohead kehren auf dem am 10. -

Chapter Five “Days of Future Passed”

Chapter Five “Days of Future Passed” Chapter 5 Overview The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) was a dramatic departure from previous rock music. No longer restricted to teenage dance music, the Sgt. Pepper album ushered in a period of music for listening or "album oriented rock" (AOR) Classic concept albums such as Days of Future Passed by the Moody Blues used orchestral settings and Pink Floyd employed electronic experimentation and the elements of the avant garde. Rock musicals such as Hair, (1967) and rock operas such as Tommy, (1968) elevated rock music to a much higher artistic level. In general, pieces become longer, more complex and experimental often using electronic music, noise, and non-western musical idioms. The hippie subculture's emphasis on visual and musical diversity encouraged rock to splinter into many sub-styles such as heavy metal, glitter/glam, progressive rock, and theatre rock. 1 The End of the Hippie Counter-Culture Movement By 1970, signs that the hippie counterculture was declining became apparent. 1. During a ten month period rock lost three of its legends: Jimi Hendrix, September 18, 1970; Janis Joplin October 4, 1970; and Jim Morrison July 3, 1971 all the result of drug related causes. 2. In 1970 four anti-war protesters were shot to death by National Guardsmen at Kent State University. Most universities were shut down in the resulting nationwide campus protests. Kent State effectively brought to an end the free speech movement at American Universities. 3. The Beatles, in many ways the spokesmen of the counterculture, broke up in 1970. -

Collection Sandretto Re Rebaudengo: a Love Meal 19 March – 9 June 2013 Gallery 7

Press Release Collection Sandretto Re Rebaudengo: A Love Meal 19 March – 9 June 2013 Gallery 7 The Whitechapel Gallery presents A Love Meal, the third in a series of displays of rarely-seen works from the Collection Sandretto Re Rebaudengo . The display brings together installations, sculptures and film which explore portraiture and the construction of identity. The centrepiece is Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres ’s “Untitled” (A Love Meal) (1992). This iconic sculpture of the 1990s consists of a hanging ribbon of 42 illuminated light bulbs created to memorialise the artist’s partner. Polish artist Pawel Althamer ’s life-size sculpture Selfportrait (1993) depicts a hyperrealistic version of the artist in old age. The nude self-portrait was submitted for Althamer’s degree show at the Art Academy in Warsaw and was created from wax and other materials. Modello di Campo 6 (1996) by German artist Tobias Rehberger includes 15 handmade vases designed for a group exhibition at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Turin. Each vase, filled with a different type of flower, represents an artist who took part in the show, from Gabriel Orozco to Sam Taylor-Wood. Other higlights in the display include 120 Days (2002) by Mexican-born Damián Ortega consisting of 120 different versions of cola bottles created by local glass blowers in Tuscany. Each with a unique shape, the bottles are transformed from disposable, mass-produced objects into desirable expressions of individualised craftsmanship. Cerith Wyn Evans ’ s red neon In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni (1996), a circular work suspended from the ceiling, illuminates the title of Guy Debord’s last film, translated as We go round and round in the night and are consumed by fire.