Mr. Bowie Changes Trains: Station to Station Written for Artist Doug

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cic004 Bowie.Pdf

4 Conversations in Creativity Explorations in inspiration Bowie • 2016 creativelancashire.org Creative Lancashire is a service provided by Lancashire County Council through its economic development company - Lancashire County Developments Ltd (LCDL). They support creative and digital businesses and work with all sectors to realise creative potential. Hemingway Design Lemn Sissay In 2011, Creative Lancashire with local design agencies Wash and JP74 launched ‘Conversations in Creativity’ - a network and series of events where creatives from across the crafts, trades and creative disciplines explore how inspiration from Simon Aldred (Cherry Ghost) around the world informs process. Previous events have featured Hemingway Design, Gary Aspden (Adidas), Pete Fowler (Animator & Artist), Donna Wilson (Designer), Cherry Ghost, I am Kloot, Nick Park (Aardman), Lemn Sissay (Poet) and Jeanette Winterson (Author) - hosted by Dave Haslam & John Robb. Donna Wilson Who’s Involved www.wash-design.co.uk www.jp74.co.uk Made You Look www.sourcecreative.co.uk Pete Fowler THE VERY BEST OF BRITANNIA 1. 2. 3. David Bowie:1947-2016 A wave of sadness and loss rippled through the This provides the context for our next creative world after legendary star man David Conversations in Creativity talk at Harris Bowie (David Robert Jones), singer, songwriter Museum as part of the Best of Britannia (BOB) and actor died on 10 January 2016. North 2016 programme, Bowie’s creative process evolved throughout his As a companion piece to the event we’ve 40+ year career, drawing inspirations from the collaborated with artists and designers including obvious to the obscure. Stephen Caton & Howard Marsden at Source Creative, and Andy Walmsley at Wash and artists; 4. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

WATCHMOJO – the Life and Career of David Bowie (1947-2016)

WATCHMOJO – The life and career of David Bowie (1947-2016) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lan_wotkon0 [Fashion] Welcome to watchmojo.com and today we're taking a look at the life and career of David Bowie. [Queen Bitch] David Robert Jones was born on January 8 1947 in Brixton London England. Though he showed musical interest at a young age it was only in the early 60s that he really pursued the art. He started by joining several blues bands but branched off on his own when they had little success. Renaming himself David Bowie he released his self-titled debut in 1967. [Who's that hiding in the apple tree clinging to a branch] Its lack of success led Bowie to participate in a promotional film called Love you till Tuesday which showcased several of his songs. A particular interest was Space Oddity : that track became a hit after it was released at the same time as the first moon landing. [Ground control to Major Tom] His sophomore effort of the same name however was another commercial disappointment. [The man who sold the world] To promote his third album The man who sold the world, Bowie was put in a dress to capitalize on his androgynous look. [Life on mars] [Ziggy Stardust] In 1971 a pop influenced record called Hunky-Dory came out and was followed by the creation of his flamboyant Ziggy Stardust persona and stage show with backing band The Spiders from Mars. Then came his breakthrough record The rise and fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars which climbed the charts thanks to his performance of the single Star Man on Top of the Pops. -

Autobituary: the Life And/As Death of David Bowie & the Specters From

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mourning Jake Cowan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13374 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13374 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jake Cowan, “Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mourning”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13374 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13374 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mournin... 1 Autobituary: the Life and/as Death of David Bowie & the Specters from Mourning Jake Cowan La mort m’attend dans un grand lit Tendu aux toiles de l’oubli Pour mieux fermer le temps qui passé — Jacques Brel, « La Mort » 1 For all his otherworldly strangeness and space-aged shimmer, the co(s)mic grandeur and alien figure(s) with which he was identified, there was nothing more constant in David Bowie’s half-century of song than death, that most and least familiar of subjects. From “Please Mr. Gravedigger,” the theatrical closing number on his 1967 self-titled debut album, to virtually every track on his final record nearly 50 years later, the protean musician mused perpetually on all matters of mortality: the loss of loved ones (“Jump They Say,” about his brother’s suicide), the apocalyptic end of the world (“Five Years”), his own impending passing. -

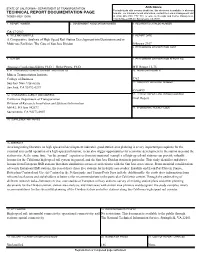

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Formats

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE formats. For alternate format information, contact the Forms Management Unit TR0003 (REV 10/98) at (916) 445-1233, TTY 711, or write to Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA-17-2969 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE A Comparative Analysis of High Speed Rail Station Development into Destination and/or Multi-use Facilities: The Case of San Jose Diridon February 2017 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris Ph.D. / Deike Peters, Ph.D. MTI Report 12-75 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER Mineta Transportation Institute College of Business 3762 San José State University 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER San José, CA 95192-0219 65A0499 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Report Division of Research, Innovation and Systems Information MS-42, PO Box 942873 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE Sacramento, CA 94273-0001 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT As a burgeoning literature on high-speed rail development indicates, good station-area planning is a very important prerequisite for the eventual successful operation of a high-speed rail station; it can also trigger opportunities for economic development in the station area and the station-city. At the same time, “on the ground” experiences from international examples of high-speed rail stations can provide valuable lessons for the California high-speed rail system in general, and the San Jose Diridon station in particular. -

Dennis Chambers

IMPROVE YOUR ACCURACY AND INDEPENDENCE! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE FUSION LEGEND DENNIS CHAMBERS SHAKIRA’S BRENDAN BUCKLEY WIN A $4,900 PEARL MIMIC BLONDIE’S PRO E-KIT! CLEM BURKE + DW ALMOND SNARE & MARCH 2019 GRETSCH MICRO KIT REVIEWED NIGHT VERSES’ ARIC IMPROTA FISHBONE’S PHILIP “FISH” FISHER THE ORIGINAL. ONLY BETTER. The 5000AH4 combines an old school chain-and-sprocket drive system and vintage-style footboard with modern functionality. Sought-after DW feel, reliability and playability. The original just got better. www.dwdrums.com PEDALS AND ©2019 Drum Workshop, Inc. All Rights Reserved. HARDWARE 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 LAYER » EXPAND » ENHANCE HYBRID DRUMMING ARTISTS BILLY COBHAM BRENDAN BUCKLEY THOMAS LANG VINNIE COLAIUTA TONY ROYSTER, JR. JIM KELTNER (INDEPENDENT) (SHAKIRA, TEGAN & SARA) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (STUDIO LEGEND) CHARLIE BENANTE KEVIN HASKINS MIKE PHILLIPS SAM PRICE RICH REDMOND KAZ RODRIGUEZ (ANTHRAX) (POPTONE, BAUHAUS) (JANELLE MONÁE) (LOVELYTHEBAND) (JASON ALDEAN) (JOSH GROBAN) DIRK VERBEUREN BEN BARTER MATT JOHNSON ASHTON IRWIN CHAD WACKERMAN JIM RILEY (MEGADETH) (LORDE) (ST. VINCENT) (5 SECONDS OF SUMMER) (FRANK ZAPPA, JAMES TAYLOR) (RASCAL FLATTS) PICTURED HYBRID PRODUCTS (L TO R): SPD-30 OCTAPAD, TM-6 PRO TRIGGER MODULE, SPD::ONE KICK, SPD::ONE ELECTRO, BT-1 BAR TRIGGER PAD, RT-30HR DUAL TRIGGER, RT-30H SINGLE TRIGGER (X3), RT-30K KICK TRIGGER, KT-10 KICK PEDAL TRIGGER, PDX-8 TRIGGER PAD (X2), SPD-SX-SE SAMPLING PAD Visit Roland.com for more info about Hybrid Drumming. Less is More Built for the gigging drummer, the sturdy aluminum construction is up to 34% lighter than conventional hardware packs. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Making West Norwood & Tulse Hill Better for Business

STATION TO STATION: MAKING WEST NORWOOD & TULSE HILL BETTER FOR BUSINESS OUR PLANS TO CREATE A BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT www.stationtostation.london 1 STATION TO STATION IS FOR INTRODUCTION ALL BUSINESSES WHO WANT Dear Friends, TO PROSPER IN A GROWING, I hope you feel as privileged as I do to work in one of the most up-and-coming parts of this great city of ours – West Norwood VIBRANT PLACE & Tulse Hill. I am always finding new ‘hidden gems’ here. “I’m really pleased Since I arrived as manager of Parkhall in 2014, the that the businesses in neighbourhood has seen massive improvements, with a new West Norwood & Tulse Hill are Leisure Centre, upgraded pavements and street furniture, the getting an opportunity to come together. BIDs elsewhere in Lambeth have always-improving Feast and an array of exciting new shops, proven very successful and have brought in bars, cafés and restaurants. extra police officers and new apprenticeships, as well as making their neighbourhoods cleaner I am proud to chair Station to Station – the proposed new and greener. Station to Station BID will help Business Improvement District (BID) for West Norwood & create a thriving business community in West Tulse Hill. By bringing local businesses together, it aims to Norwood & Tulse Hill” take the area to another level. We believe it will make owners, Cllr Jack Hopkins, Cabinet Member customers, staff and clients happier and attract new ones. for Regeneration, Business and Culture, London Borough In the pages that follow you will read about all the exciting of Lambeth. things that Station to Station BID plans to do. -

Itinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart from His

PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME XXIII SUPPLEMENT TO THE LYON IN MOURNING PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART ITINERARY AND MAP April 1897 ITINERARY OF PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART FROM HIS LANDING IN SCOTLAND JULY 1746 TO HIS DEPARTURE IN SEPTEMBER 1746 Compiled from The Lyon in Mourning supplemented and corrected from other contemporary sources by WALTER BIGGAR BLAIKIE With a Map EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1897 April 1897 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A List of Authorities cited and Abbreviations used ................................................................................. 8 ITINERARY .................................................................................................................................................. 9 ARRIVAL IN SCOTLAND .................................................................................................................. 9 LANDING AT BORRADALE ............................................................................................................ 10 THE MARCH TO CORRYARRACK .................................................................................................. 13 THE HALT AT PERTH ..................................................................................................................... 14 THE MARCH TO EDINBURGH ...................................................................................................... -

The Age of Bowie 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE AGE OF BOWIE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Morley | 9781501151170 | | | | | The Age of Bowie 1st edition PDF Book His new manager, Ralph Horton, later instrumental in his transition to solo artist soon witnessed Bowie's move to yet another group, the Buzz, yielding the singer's fifth unsuccessful single release, " Do Anything You Say ". Now, Morley has published his personal account of the life, musical influence and cultural impact of his teenage hero, exploring Bowie's constant reinvention of himself and his music over a period of five extraordinarily innovative decades. I think Britain could benefit from a fascist leader. After completing Low and "Heroes" , Bowie spent much of on the Isolar II world tour , bringing the music of the first two Berlin Trilogy albums to almost a million people during 70 concerts in 12 countries. Matthew McConaughey immediately knew wife Camila was 'something special'. Did I learn anything new? Reuse this content. Studying avant- garde theatre and mime under Lindsay Kemp, he was given the role of Cloud in Kemp's theatrical production Pierrot in Turquoise later made into the television film The Looking Glass Murders. Hachette UK. Time Warner. Retrieved 4 October About The Book. The line-up was completed by Tony and Hunt Sales , whom Bowie had known since the late s for their contribution, on bass and drums respectively, to Iggy Pop's album Lust for Life. The Sydney Morning Herald. Morely overwrites, taking a significant chunk of the book's opening to beat Bowie's death to death, the takes the next three-quarters of the book to get us through the mid-Sixties to the end of the Seventies, then a ridiculously few yet somehow still overwritten pages to blast through the Eighties, Nineties, and right up to Blackstar and around to his death again. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction Tuesday 19th February 2019 at 10.00 Viewing: For enquiries relating to the auction Monday 18th February 2019 10:00 - 16:00 please contact: 09:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment Music www.specialauctionservices.com As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indications of the provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. ORDER OF AUCTION Music Hall & other Disc Records 1-68 Cylinder Records 69-108 Phonographs & Gramophones 109-149 Technical Apparatus 150-155 Musical Boxes 156-171 Jazz/ other 78s 172-184 Vinyl Records 185-549 Reel to Reel Tapes 550-556 CDs/ CD Box Sets 557-604 DVDs 605-612 Music Memorabilia 613-658 Music Posters 659-666 Film & Entertainment Memorabilia Including items from the Estate of John Inman 667-718 Film Posters 719-743 Musical Instruments 744-759 Hi-Fi 760-786 2 www.specialauctionservices.com MUSIC HALL & OTHER DISC RECORDS 18. Music hall and similar records, 10 inch, 67, by Geo Robey (G & T 2-2721 & 18 1. -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context.