Using Hydrogen As a Nucleophile in Hydride Reductions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport of Dangerous Goods

ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Recommendations on the TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS Model Regulations Volume I Sixteenth revised edition UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Copyright © United Nations, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. UNITED NATIONS Sales No. E.09.VIII.2 ISBN 978-92-1-139136-7 (complete set of two volumes) ISSN 1014-5753 Volumes I and II not to be sold separately FOREWORD The Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods are addressed to governments and to the international organizations concerned with safety in the transport of dangerous goods. The first version, prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Council's Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, was published in 1956 (ST/ECA/43-E/CN.2/170). In response to developments in technology and the changing needs of users, they have been regularly amended and updated at succeeding sessions of the Committee of Experts pursuant to Resolution 645 G (XXIII) of 26 April 1957 of the Economic and Social Council and subsequent resolutions. -

Process for Purification of Ethylene Compound Having Fluorine-Containing Organic Group

Office europeen des brevets (fi) Publication number : 0 506 374 A1 @ EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION @ Application number: 92302586.0 @ Int. CI.5: C07C 17/38, C07C 21/18 (g) Date of filing : 25.03.92 (30) Priority : 26.03.91 JP 86090/91 (72) Inventor : Kishita, Hirofumi 3-19-1, Isobe, Annaka-shi Gunma-ken (JP) (43) Date of publication of application : Inventor : Sato, Shinichi 30.09.92 Bulletin 92/40 3-5-5, Isobe, Annaka-shi Gunma-ken (JP) Inventor : Fujii, Hideki (84) Designated Contracting States : 3-12-37, Isobe, Annaka-shi DE FR GB Gunma-ken (JP) Inventor : Matsuda, Takashi 791 ~4 YdndSG Anri3k3~shi @ Applicant : SHIN-ETSU CHEMICAL CO., LTD. Gunma-ken (JP) 6-1, Ohtemachi 2-chome Chiyoda-ku Tokyo (JP) @) Representative : Votier, Sidney David et al CARPMAELS & RANSFORD 43, Bloomsbury Square London WC1A 2RA (GB) (54) Process for purification of ethylene compound having fluorine-containing organic group. (57) A process for purifying an ethylene compound having a fluorine-containing organic group (fluorine- containing ethylene compound) by mixing the fluorine-containing ethylene compound with an alkali metal or alkaline earth metal reducing agent, and subjecting the resulting mixture to irradiation with ultraviolet radiation, followed by washing with water. The purification process ensures effective removal of iodides which are sources of molecular iodine, from the fluorine-containing ethylene compound. < h- CO CO o 10 o Q_ LU Jouve, 18, rue Saint-Denis, 75001 PARIS EP 0 506 374 A1 BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION 1. Field of the Invention 5 The present invention relates to a process for purifying an ethylene compound having a fluorine-containing organic group, and more particularly to a purification process by which iodine contained as impurity in an ethylene compound having a fluorine-containing organic group can be removed effectively. -

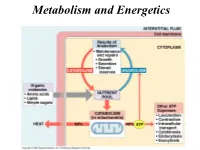

Metabolism and Energetics Oxidation of Carbon Atoms of Glucose Is the Major Source of Energy in Aerobic Metabolism

Metabolism and Energetics Oxidation of carbon atoms of glucose is the major source of energy in aerobic metabolism C6H1206 + 6O2 yields 6 CO2 + H20 + energy Energy released ΔG = - 686 kcal/mol Glucose oxidation requires over 25 discrete steps, with production of 36 ATP. Energy Transformations The mitochondrial synthesis of ATP is not stochiometric. Electron–motive force Proton-motive force Phosphoryl-transfer potential in the form of ATP. Substrate level phosphorylation The formation of ATP by substrate-level phosphorylation ADP ATP P CH O P CH2 O P 2 is used to represent HC OH HC OH a phosphate ester: phosphoglycerate CH OH OH CH2 O P kinase 2 P O bisphosphoglycerate 3-phosphoglycerate OH ADP ATP CH2 CH2 CH3 C O P C OH C O pyruvate kinase non-enzymic COOH COOH COOH phosphoenolpyruvate enolpyruvate pyruvate Why ATP? The reaction of ATP hydrolysis is very favorable ΔGo = - 30.5 kJ/mol = - 7.3 kCal/mol 1. Charge separation of closely packed phosphate groups provides electrostatic relief. Mg2+ 2. Inorganic Pi, the product of the reaction, is immediately resonance-stabilized (electron density spreads equally to all oxygens). 3. ADP immediately ionizes giving H+ into a low [H+] environment (pH~7). 4. Both Pi and ADP are more favorably solvated by water than one ATP molecule. 5. ATP is water soluble. The total body content of ATP and ADP is under 350 mmol – about 10 g, BUT … the amount of ATP synthesized and used each day is about 150 mol – about 110 kg. ATP Production - stage 1 - Glycolysis Glycolysis When rapid production of ATP is needed. -

Herbert Charles Brown, a Biographical Memoir

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES H E R B E R T Ch ARLES BROWN 1 9 1 2 — 2 0 0 4 A Biographical Memoir by E I-I CH I N EGIS HI Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2008 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. Photograph Credit Here. HERBERT CHARLES BROWN May 22, 1912–December 19, 2004 BY EI -ICH I NEGISHI ERBERT CHARLES BROWN, R. B. Wetherill Research Profes- Hsor Emeritus of Purdue University and one of the truly pioneering giants in the field of organic-organometallic chemistry, died of a heart attack on December 19, 2004, at age 92. As it so happened, this author visited him at his home to discuss with him an urgent chemistry-related matter only about 10 hours before his death. For his age he appeared well, showing no sign of his sudden death the next morn- ing. His wife, Sarah Baylen Brown, 89, followed him on May 29, 2005. They were survived by their only child, Charles A. Brown of Hitachi Ltd. and his family. H. C. Brown shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1979 with G. Wittig of Heidelberg, Germany. Their pioneering explorations of boron chemistry and phosphorus chemistry, respectively, were recognized. Aside from several biochemists, including V. du Vigneaud in 1955, H. C. Brown was only the second American organic chemist to win a Nobel Prize behind R. B. Woodward, in 1965. His several most significant contribu- tions in the area of boron chemistry include (1) codiscovery of sodium borohyride (1972[1], pp. -

Suplementary Information

Supplementary Material (ESI) for Polymer Chemistry This journal is (c) The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 SUPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Shedding the hydrophobic mantel of polymersomes René P. Brinkhuis, Taco R. Visser, Floris P. J. T. Rutjes, Jan C.M. van Hest* Radboud University Nijmegen,, Institute for Molecules and Materials, Heyendaalseweg 135, 6525 AJ Nijmegen, The Netherlands; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Contents: Experimental General note Materials Instrumentation α- methoxy ω-methyl ester poly(ethylene glycol) α- methoxy ω-hydrazide poly(ethylene glycol) α- azido ω-methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) Aldehyde terminated polybutadiene Alkyne terminated polybutadiene Polybutadiene-Hz-poly(ethylene glycol) Polybutadiene-b-poly(ethylene glycol) Vesicle preparation Stability studies Notes and References Figures Figure 1: GPC traces of polymer 1 and its constituents. Figure 2: GPC traces of polymer 2 and its constituents. Figure 3: GPC traces of polymer 3 and its constituents. Figure 4: GPC traces of polymer 4 and its constituents. Supplementary Material (ESI) for Polymer Chemistry This journal is (c) The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Experimental section General note: All reactions are described for the lower molecular weight analogue, polyethylene glycol 1000, indicated with an A. The procedures for the polyethylene glycol 2000 analogues, indicated with B, are the same, starting with equimolar amounts. Materials: Sec-butyllithium (ALDRICH 1.4M in hexane), 1,3 butadiene (SIGMA ALDRICH, 99+%), 3- bromo-1-(trimethylsilyl-1-propyne) (ALDRICH, 98%), tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) (ALDRICH, 1.0M in THF), polyethylene glycol 1000 monomethyl ether (FLUKA), polyethylene glycol 2000 monomethyl ether (FLUKA), methanesulfonyl chloride (MsCl) (JANSSEN CHIMICA, 99%), sodium azide (ACROS ORGANICS, 99% extra pure), sodium hydride (ALDRICH, 60% dispersion in mineral oil), copper bromide (CuBr) (FLUKA, >98%), N,N,N’,N’,N”-penta dimethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA) (Aldrich,99%), hydrazine (ALDRICH, 1M in THF) were used as received. -

United States Patent (19) 11) 4,219,685 Savini 45 Aug

United States Patent (19) 11) 4,219,685 Savini 45 Aug. 26, 1980 (54) IMPROVING ODOR OF ISOPROPANOL Attorney, Agent, or Firm-C. Leon Kim; Rebecca Yablonsky 75 Inventor: Charles Savini, Warren, N.J. 57 ABSTRACT 73 Assignee: Exxon Research & Engineering Co., Methods for deodorizing lower alcohols such as ethanol Florham Park, N.J. and isopropyl alcohol and their oxy derivatives such as ethers and esters are disclosed, including contacting 21 Appl. No.: 31,761 these compounds with a deodorizing contact mass com 22 Filed: Apr. 20, 1979 prising, on a support, metals and/or metal oxides, pref erably of the metals of Group IB, VIB and VIII of the Periodic Table, where the metal oxides are at least par Related U.S. Application Data tially reduced to metal and the deodorizing contact 63 Continuation-in-part of Ser. No. 908,910, May 24, mass has a minimum particle dimension of greater than 1978, abandoned, which is a continuation-in-part of about 0.254 mm so as to be in a form suitable for use in Ser. No. 834,240, Sep. 19, 1977, abandoned. a fixed bed contacting process. In a preferred embodi ment, isopropyl alcohol is deodorized employing such 51 Int. Cl’.............................................. CO7C 29/24 deodorizing contact masses, preferably comprising 52 U.S. Cl. .............. ... 568/917; 568/922 Group VIII metals such as nickel, iron, cobalt and the 58) Field of Search ................................ 568/917,922 like, on a support, so that the contact mass has a surface 56) References Cited area less than about 1,500 m2 per gram. -

Sodium Borohydride

Version 6.6 SAFETY DATA SHEET Revision Date 01/21/2021 Print Date 09/25/2021 SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1 Product identifiers Product name : Sodium borohydride Product Number : 452882 Brand : Aldrich CAS-No. : 16940-66-2 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Identified uses : Laboratory chemicals, Synthesis of substances 1.3 Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Company : Sigma-Aldrich Inc. 3050 SPRUCE ST ST. LOUIS MO 63103 UNITED STATES Telephone : +1 314 771-5765 Fax : +1 800 325-5052 1.4 Emergency telephone Emergency Phone # : 800-424-9300 CHEMTREC (USA) +1-703- 527-3887 CHEMTREC (International) 24 Hours/day; 7 Days/week SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture GHS Classification in accordance with 29 CFR 1910 (OSHA HCS) Chemicals which, in contact with water, emit flammable gases (Category 1), H260 Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 3), H301 Skin corrosion (Category 1B), H314 Serious eye damage (Category 1), H318 Reproductive toxicity (Category 1B), H360 For the full text of the H-Statements mentioned in this Section, see Section 16. 2.2 GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Aldrich - 452882 Page 1 of 9 The life science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany operates as MilliporeSigma in the US and Canada Hazard statement(s) H260 In contact with water releases flammable gases which may ignite spontaneously. H301 Toxic if swallowed. H314 Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. H360 May damage fertility or the unborn child. -

WTR-Core Product Code SMI2337-1 SDS No

Conforms to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 (REACH), Annex II, as amended by Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/830 SAFETY DATA SHEET SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1 Product identifier Product name WTR-Core Product code SMI2337-1 SDS no. SMI2337-1 Product type Paste 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Use of the substance/ Analytical reagent that is mixed with activator to form a test kit. mixture For specific application advice see appropriate Technical Data Sheet or consult our company representative. 1.3 Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Supplier BP Marine Limited Chertsey Road Sunbury-on-Thames Middlesex TW16 7LN United Kingdom E-mail address [email protected] 1.4 Emergency telephone number EMERGENCY Carechem: +44 (0) 1235 239 670 (24/7) TELEPHONE NUMBER SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture Product definition Mixture Classification according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008 [CLP/GHS] Not classified. Ingredients of unknown Percentage of the mixture consisting of ingredient(s) of unknown acute oral toxicity: 1% toxicity Percentage of the mixture consisting of ingredient(s) of unknown acute dermal toxicity: 1% Percentage of the mixture consisting of ingredient(s) of unknown acute inhalation toxicity: 1% Ingredients of unknown Percentage of the mixture consisting of ingredient(s) of unknown hazards to the aquatic ecotoxicity environment: 1% See sections 11 and 12 for more detailed information on health effects and symptoms and environmental hazards. 2.2 Label elements Signal word No signal word. -

Part I. the Total Synthesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lester Percy Joseph Burton forthe degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry presentedon March 20, 1981. Title: Part 1 - The Total Synthesis of (±)-Cinnamodialand Related Drimane Sesquiterpenes Part 2 - Photochemical Activation ofthe Carboxyl Group Via NAcy1-2-thionothiazolidines Abstract approved: Redacted for privacy DT. James D. White Part I A total synthesis of the insect antifeedant(±)-cinnamodial ( ) and of the related drimanesesquiterpenes (±)-isodrimenin (67) and (±)-fragrolide (72)are described from the diene diester 49. Hydro- boration of 49 provided the C-6oxygenation and the trans ring junction in the form of alcohol 61. To confirm the stereoselectivity of the hydroboration, 61 was convertedto both (t)-isodrimenin (67) and (±)-fragrolide (72) in 3 steps. A diisobutylaluminum hydride reduction of 61 followed by a pyridiniumchlorochromate oxidation and treatment with lead tetraacetate yielded the dihydrodiacetoxyfuran102. The base induced elimination of acetic acid preceded theepoxidation and provided 106 which contains the desired hydroxy dialdehydefunctionality of cinnamodial in a protected form. The epoxide 106 was opened with methanol to yield the acetal 112. Reduction, hydrolysis and acetylation of 112 yielded (t)- cinnamodial in 19% overall yield. Part II - Various N- acyl- 2- thionothiazolidineswere prepared and photo- lysed in the presence of ethanol to provide the corresponding ethyl esters. The photochemical activation of the carboxyl function via these derivatives appears, for practical purposes, to be restricted tocases where a-keto hydrogen abstraction and subsequent ketene formation is favored by acyl substitution. Part 1 The Total Synthesis of (±)-Cinnamodial and Related Drimane Sesquiterpenes. Part 2 Photochemical Activation of the Carboxyl Group via N-Acy1-2-thionothiazolidines. -

Reactions of Benzene & Its Derivatives

Organic Lecture Series ReactionsReactions ofof BenzeneBenzene && ItsIts DerivativesDerivatives Chapter 22 1 Organic Lecture Series Reactions of Benzene The most characteristic reaction of aromatic compounds is substitution at a ring carbon: Halogenation: FeCl3 H + Cl2 Cl + HCl Chlorobenzene Nitration: H2 SO4 HNO+ HNO3 2 + H2 O Nitrobenzene 2 Organic Lecture Series Reactions of Benzene Sulfonation: H 2 SO4 HSO+ SO3 3 H Benzenesulfonic acid Alkylation: AlX3 H + RX R + HX An alkylbenzene Acylation: O O AlX H + RCX 3 CR + HX An acylbenzene 3 Organic Lecture Series Carbon-Carbon Bond Formations: R RCl AlCl3 Arenes Alkylbenzenes 4 Organic Lecture Series Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution • Electrophilic aromatic substitution: a reaction in which a hydrogen atom of an aromatic ring is replaced by an electrophile H E + + + E + H • In this section: – several common types of electrophiles – how each is generated – the mechanism by which each replaces hydrogen 5 Organic Lecture Series EAS: General Mechanism • A general mechanism slow, rate + determining H Step 1: H + E+ E El e ctro - Resonance-stabilized phile cation intermediate + H fast Step 2: E + H+ E • Key question: What is the electrophile and how is it generated? 6 Organic Lecture Series + + 7 Organic Lecture Series Chlorination Step 1: formation of a chloronium ion Cl Cl + + - - Cl Cl+ Fe Cl Cl Cl Fe Cl Cl Fe Cl4 Cl Cl Chlorine Ferric chloride A molecular complex An ion pair (a Lewis (a Lewis with a positive charge containing a base) acid) on ch lorine ch loronium ion Step 2: attack of -

Electroless Nickel, Alloy, Composite and Nano Coatings - a Critical Review

Electroless nickel, alloy, composite and nano coatings - A critical review Sudagar, J., Lian, J., & Sha, W. (2013). Electroless nickel, alloy, composite and nano coatings - A critical review. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 571, 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.03.107 Published in: Journal of Alloys and Compounds Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2013 Elsevier. This manuscript is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 ELECTROLESS NICKEL, ALLOY, COMPOSITE AND NANO COATINGS - A CRITICAL REVIEW Jothi Sudagar Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology- Madras (IIT-M), Chennai - 600 036, India Jianshe Lian College of Materials Science and Engineering, Jilin University, Changchun 130025, China. -

Calcium Hydride, Grade S

TECHNICAL DATA SHEET Date of Issue: 2016/09/02 Calcium Hydride, Grade S CAS-No. 7789-78-8 EC-No. 232-189-2 Molecular Formula CaH₂ Product Number 455150 APPLICATION Calcium hydride is used primarily as a source of hydrogen, as a drying agent for liquids and gases, and as a reducing agent for metal oxides. SPECIFICATION Ca total min. 92 % H min. 980 ml/g CaH2 Mg max. 0.8 % N max. 0.2 % Al max. 0.01 % Cl max. 0.5 % Fe max. 0.01 % METHOD OF ANALYSIS Calcium complexometric, impurities by spectral analysis and special analytical procedures. Gas volumetric determination of hydrogen. Produces with water approx. 1,010 ml hydrogen per gram. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Appearance powder Color gray white The information presented herein is believed to be accurate and reliable, but is presented without guarantee or responsibility on the part of Albemarle Corporation and its subsidiaries and affiliates. It is the responsibility of the user to comply with all applicable laws and regulations and to provide for a safe workplace. The user should consider any health or safety hazards or information contained herein only as a guide, and should take those precautions which are necessary or prudent to instruct employees and to develop work practice procedures in order to promote a safe work environment. Further, nothing contained herein shall be taken as an inducement or recommendation to manufacture or use any of the herein materials or processes in violation of existing or future patent. Technical data sheets may change frequently. You can download the latest version from our website www.albemarle-lithium.com.