Georgian Dream's Foreign Policies: an Attempt to Change the Paradigm?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia's October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications

Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs November 4, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43299 Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Summary This report discusses Georgia’s October 27, 2013, presidential election and its implications for U.S. interests. The election took place one year after a legislative election that witnessed the mostly peaceful shift of legislative and ministerial power from the ruling party, the United National Movement (UNM), to the Georgia Dream (GD) coalition bloc. The newly elected president, Giorgi Margvelashvili of the GD, will have fewer powers under recently approved constitutional changes. Most observers have viewed the 2013 presidential election as marking Georgia’s further progress in democratization, including a peaceful shift of presidential power from UNM head Mikheil Saakashvili to GD official Margvelashvili. Some analysts, however, have raised concerns over ongoing tensions between the UNM and GD, as well as Prime Minister and GD head Bidzini Ivanishvili’s announcement on November 2, 2013, that he will step down as the premier. In his victory speech on October 28, Margvelashvili reaffirmed Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation, including the pursuit of Georgia’s future membership in NATO and the EU. At the same time, he reiterated that GD would continue to pursue the normalization of ties with Russia. On October 28, 2013, the U.S. State Department praised the Georgian presidential election as generally democratic and expressing the will of the people, and as demonstrating Georgia’s continuing commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration. -

Georgia Between Dominant-Power Politics, Feckless Pluralism, and Democracy Christofer Berglund Uppsala University

GEORGIA BETWEEN DOMINANT-POWER POLITICS, FECKLESS PLURALISM, AND DEMOCRACY CHRISTOFER BERGLUND UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Abstract: This article charts the last decade of Georgian politics (2003-2013) through theories of semi- authoritarianism and democratization. It first dissects Saakashvili’s system of dominant-power politics, which enabled state-building reforms, yet atrophied political competition. It then analyzes the nested two-level game between incumbents and opposition in the run-up to the 2012 parliamentary elections. After detailing the verdict of Election Day, the article turns to the tense cohabitation that next pushed Georgia in the direction of feckless pluralism. The last section examines if the new ruling party is taking Georgia in the direction of democratic reforms or authoritarian closure. nder what conditions do elections in semi-authoritarian states spur Udemocratic breakthroughs?1 This is a conundrum relevant to many hybrid regimes in the region of the former Soviet Union. It is also a ques- tion of particular importance for the citizens of Georgia, who surprisingly voted out the United National Movement (UNM) and instead backed the Georgian Dream (GD), both in the October 2012 parliamentary elections and in the October 2013 presidential elections. This article aims to shed light on the dramatic, but not necessarily democratic, political changes unleashed by these events. It is, however, beneficial to first consult some of the concepts and insights that have been generated by earlier research on 1 The author is grateful to Sten Berglund, Ketevan Bolkvadze, Selt Hasön, and participants at the 5th East Asian Conference on Slavic-Eurasian Studies, as well as the anonymous re- viewers, for their useful feedback. -

Regulating Trans-Ingur/I Economic Relations Views from Two Banks

RegUlating tRans-ingUR/i economic Relations Views fRom two Banks July 2011 Understanding conflict. Building peace. this initiative is funded by the european union about international alert international alert is a 25-year-old independent peacebuilding organisation. We work with people who are directly affected by violent conflict to improve their prospects of peace. and we seek to influence the policies and ways of working of governments, international organisations like the un and multinational companies, to reduce conflict risk and increase the prospects of peace. We work in africa, several parts of asia, the south Caucasus, the Middle east and Latin america and have recently started work in the uK. our policy work focuses on several key themes that influence prospects for peace and security – the economy, climate change, gender, the role of international institutions, the impact of development aid, and the effect of good and bad governance. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding nGos with more than 155 staff based in London and 15 field offices. to learn more about how and where we work, visit www.international-alert.org. this publication has been made possible with the help of the uK Conflict pool and the european union instrument of stability. its contents are the sole responsibility of international alert and can in no way be regarded as reflecting the point of view of the european union or the uK government. © international alert 2011 all rights reserved. no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. -

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2013

Chronicle: The Caucasus In the Year 2013 January 9 January 2013 The Georgian State audit agency launches a probe into the alleged violation of funding political parties’ rules by the United National Movement during the electoral campaign of 2012 11 January 2013 Russian President Vladimir Putin congratulates the head of the Georgian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Ilia II, on his 80th birthday 18 January 2013 During an official visit to Armenia, Georgian Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili promises to the head of the Holy Armenian Apostolic Church Catholicos Karekin II that Armenian history will soon be taught in Georgian schools 19 January 2013 police in Baku clash with shopkeepers protesting a rent increase by the managers of Azerbaijan’s largest shopping center 24 January 2013 The Azerbaijani police break up protests in the town of Ismayilli demanding the resignation of the local governor Nizami Alekberov 26 January 2013 Hundreds of people demonstrate in Baku to express their solidarity with the protests in the town of Ismayilli and some 40 participants are detained by the police including the blogger Emin Milli and investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova 26 January 2013 A statue of Azerbaijan’s late President Heydar Aliyev is removed from a park in Mexico City 27 January 2013 Three activists involved in a 26 January protest in the Azerbaijani capital of Baku are given prison sentences 28 January 2013 The Azerbaijani and Armenian foreign ministers meet in Paris for talks mediated by the OSCE Minsk Group and aimed at settling the conflict -

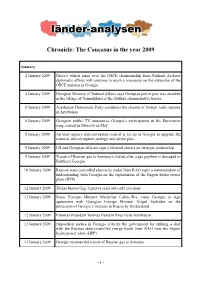

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

Abkhazia to Be Included in Even More Distant

caucasus analytical caucasus analytical digest 07/09 digest rity? Which flexible arrangements are conceivable for zia, whether in the framework of a common state or the issuing of visas for Abkhaz holders of Georgian as two cooperating independent states, have become passports that would allow Abkhazia to be included in even more distant. The same is true to an even greater European education and exchange programs? extent for the possible integration of both into a “polit- Which measures would allow the EU to enhance ical Europe” expanded to include the Black Sea region. the efficiency of its necessary long-term engagement on Nevertheless, that seems to be the only alternative to the behalf of political and legal reforms in Georgia? The suc- development that currently seems to be the most likely cess of these reforms is a precondition for the country’s one, namely a factual annexation of the small Abkhaz peaceful domestic consolidation and thus also for greater state by Russia in a Southern Caucasus that will likely flexibility towards the secessionist republics. be afflicted by geopolitical confrontation and instabil- Since the events of August 2008, the prospects of ity for a long time to come. peaceful reconciliation between Georgia and Abkha- Translated from German by Christopher Findlay About the Author Walter Kaufmann is an independent analyst and the former director (2002–2008) of the Heinrich Böll Foundation South Caucasus. Opinion Georgia’s Relationship with Abkhazia By Paata Zakareisvili, Tbilisi Abstract The August 2008 conflict between Georgia and Russia fundamentally changed the situation regarding the separatist territories in Georgia, fundamentally strengthening Russia’s position. -

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2014

Chronicle: The Caucasus In the Year 2014 January 1 January 2014 The Georgian State Ministry for Reintegration is renamed into State Ministry for Reconciliation and Civic Equality in a move that Tbilisi officials say will help engagement with the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia 4 January 2014 Russia pledges over 180 million dollars to the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2014–2016 through a decree signed by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev with the financial aid to be provided via the Russian Ministry of Construction 14 January 2014 Hungary becomes the twelfth country to recognize Georgia’s neutral travel documents designed for residents of the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia 16 January 2014 Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili says that Russia lacks the levers to deter the country’s signing of an Association Agreement with the European Union although provocations are expected 20 January 2014 Georgian President Giorgi Margvelashvili meets with his Turkish counterpart Abdullah Gül and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during a visit to Turkey that includes meetings with representatives of the Georgian diaspora 30 January 2014 Czech President Milos Zeman says during Armenian President Serzh Sarkisian’s official visit to Prague that the mass killings of Armenians during the Ottoman empire amounted to a “genocide” February 3 February 2014 Azerbaijani parliament speaker Oqtay Asadov calls on religious clerics to perform prayers in Azeri and not in Arabic to make it easier for people to -

Georgia: European Ambitions and Regional Challenges

Transcript Georgia: European Ambitions and Regional Challenges Dr Maia Panjikidze Minister of Foreign Affairs, Georgia Chair: James Nixey Head, Russia and Eurasia Programme, Chatham House 11 June 2014 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/ speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Georgia: European Ambitions and Regional Challenges James Nixey Ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. I am absolutely delighted to have Dr Maia Panjikidze here with us in Chatham House. I’ve always said that one thing about Georgia, apart from the fact its politics are always interesting and never dull – you can take that any way you wish – is that the Georgians have always been excellent at sending over their most senior politicians and articulating their point of view on local and wider politics. -

Como Exportar Geórgia

Como Exportar Geórgia entre Ministério das Relações Exteriores Departamento de Promoção Comercial e Investimentos Divisão de Informação Comercial Como Exportar Geórgia Sumário SUMÁRIO VI – ESTRUTURA DE COMÉRCIO............................50 1..Canais.de.distribuição.......................................... 50 INTRODUÇÃO.........................................................2 2..Promoção.de.vendas............................................ 53 MAPA......................................................................3 3..Práticas.comerciais.............................................. 55 DADOS BÁSICOS.....................................................4 VII - RECOMENDAÇÕES ÀS EMPRESAS BRASILEIRAS 60 I – ASPECTOS GERAIS............................................5 1. Geografia.............................................................5 ANEXOS................................................................62 2..População.............................................................6 I.–.ENDEREÇOS...................................................... 62 3..Transportes.e.comunicações.................................. 12 II.–.TRANSPORTES.E.COMUNICAÇÕES.COM. 4..Estrutura.política.e.administrativa.......................... 15 .......O.BRASIL........................................................ 79 5..Participação.em.organizações.internacionais............ 18 III.–.INFORMAÇÕES.SOBRE.SGP............................... 79 IV.–.INFORMAÇÕES.PRÁTICAS.................................. 80 II – ECONOMIA, MOEDA E FINANÇAS...................20 1..Perspectiva.econômica........................................ -

Abkhazia: the Long Road to Reconciliation

Abkhazia: The Long Road to Reconciliation Europe Report N°224 | 10 April 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Political Realities in Abkhazia .......................................................................................... 3 A. Russia’s Military Presence ......................................................................................... 3 B. Russian Financial Dependence .................................................................................. 6 C. Property and Other Disputes ..................................................................................... 8 III. Overcoming Obstacles in the Georgia-Russia Standoff and Abkhazia ........................... 12 A. Georgia-Russia Relations .......................................................................................... 12 B. The Geneva International Discussions and Humanitarian Issues ............................ 13 C. The Non-Use of Force ............................................................................................... -

The Brookings Institution the Political Crisis in Georgia

GEORGIA-2009/06/17 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION THE POLITICAL CRISIS IN GEORGIA: PROSPECTS FOR RESTORATION Washington, D.C. Wednesday, June 17, 2009 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction: CARLOS PASCUAL Vice President and Director Foreign Policy Studies, The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: IRAKLI ALASANIA Former U.N. Ambassador Head of Alliance for Georgia Moderator: STEVEN PIFER Acting Director, Center for the United States and Europe (CUSE) The Brookings Institution * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 GEORGIA-2009/06/17 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. PASCUAL: Good afternoon. My name is Carlos Pascual. I'm one of the Vice Presidents of Brookings, and the Director of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, and it's a real pleasure to welcome you to this discussion with Irakli Alasania on Georgia, it's democratic roots and its future as an independent state and the future of his democracy. It's a real pleasure to welcome you to this discussion and to welcome Irakli here to Brookings. He, as an individual, is actually a symbolic of a new generation, and what is easy to call the former Soviet states but in fact is something different, and we still are in search of a better name for it. But he's someone who has lived his professional career in an independent Georgia, which is in fact a startling transition and new reality. And it's one that despite all of the challenges and difficulties that we have seen over the years, is one from which we should take encouragement that Georgia has gained its independence, it's sustained its independence, and that there is now a new breed of young professional who are accomplished and whose reality is an independent Georgian state, and they will never go back from that independent Georgian state. -

Getting Georgia Right

Getting Georgia Right Svante Cornell Getting Georgia Right Getting Georgia Right Svante Cornell CREDITS Centre for European Studies Rue du Commerce 20 B-1000 Brussels The Centre for European Studies (CES) is the political foundation and think tank of the Euro- pean People’s Party (EPP), dedicated to the promotion of Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. For more information please visit: www.thinkingeurope.eu Editor: Ingrid Habets, Research Officer (CES), [email protected] External editing: Communicative English bvba Typesetting: Victoria Agency Layout and cover design: RARO S.L. Printed in Belgium by Drukkerij Jo Vandenbulcke This publication receives funding from the European Parliament. © Centre for European Studies 2013 The European Parliament and the Centre for European Studies assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Sole responsibility lies with the author of this publication. 2 Getting Georgia Right About the CES The Centre for European Studies (CES), established in 2007, is the political foundation of the European People’s Party (EPP). The CES embodies a pan-European mindset, promoting Christian Democrat, conservative and like-minded political values. It serves as a framework for national political foundations linked to member parties of the EPP. It currently has 26 member foundations in 20 EU and non-EU countries. The CES takes part in the preparation of EPP programmes and policy documents. It organises seminars and training on EU policies and on the process of European integration. The CES also contributes to formulating EU and national public policies. It produces research studies and books, electronic newsletters, policy briefs, and the twice-yearly European View journal.