Enges to Georgia’S Sovereign Interests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom of Religion in Abkhazia and South Ossetia/Tskhinvali Region

Freedom of Religion in Abkhazia and South Ossetia/Tskhinvali Region Brief prehistory Orthodox Christians living in Abkhazia and South Ossetia are considered by the Patriarchate of the Georgian Orthodox Church to be subject to its canonical jurisdiction. The above is not formally denied by any Orthodox Churches. Abkhazians demand full independence and imagine their Church also to be independent. As for South Ossetia, the probable stance of "official" Ossetia is to unite with Alanya together with North Ossetia and integrate into the Russian Federation, therefore, they do not want to establish or "restore" the Autocephalous Orthodox Church. In both the political and ecclesiastical circles, the ruling elites of the occupied territories do not imagine their future together with either the Georgian State or the associated Orthodox Church. As a result of such attitudes and Russian influence, the Georgian Orthodox Church has no its clergymen in Tskhinvali or Abkhazia, cannot manage the property or relics owned by it before the conflict, and cannot provide adequate support to the parishioners that identify themselves with the Georgian Orthodox Church. Although both Abkhazia and South Ossetia have state sovereignty unilaterally recognized by the Russian Federation, ecclesiastical issues have not been resolved in a similar way. The Russian Orthodox Church does not formally or officially recognize the separate dioceses in these territories, which exist independently from the Georgian Orthodox Church, nor does it demand their integration into its own space. Clearly, this does not necessarily mean that the Russian Orthodox Church is guided by the "historical truth" and has great respect for the jurisdiction of the Georgian Orthodox Church in these territories. -

Russia, Georgia and the Eu in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION: RUSSIA, GEORGIA AND THE EU IN ABKHAZIA AND SOUTH OSSETIA Iskra Kirova August 2012 Figueroa Press Los Angeles The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and cannot be interpreted to reflect the positions of organizations that the author is affiliated with. PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION: RUSSIA, GEORGIA AND THE EU IN ABKHAZIA AND SOUTH OSSETIA Iskra Kirova Published by FIGUEROA PRESS 840 Childs Way, 3rd Floor Los Angeles, CA 90089 Phone: (213) 743-4800 Fax: (213) 743-4804 www.figueroapress.com Figueroa Press is a division of the USC Bookstore Copyright © 2012 all rights reserved Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the author, care of Figueroa Press. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor Figueroa nor the USC Bookstore shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by any text contained in this book. Figueroa Press and the USC Bookstore are trademarks of the University of Southern California ISBN 13: 978-0-18-214016-9 ISBN 10: 0-18-214016-4 For general inquiries or to request additional copies of this paper please contact: USC Center on Public Diplomacy at the Annenberg School University of Southern California 3502 Watt Way, G4 Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 Tel: (213) 821-2078; Fax: (213) 821-0774 [email protected] www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org CPD Perspectives on Public Diplomacy CPD Perspectives is a periodic publication by the USC Center on Public Diplomacy, and highlights scholarship intended to stimulate critical thinking about the study and practice of public diplomacy. -

Regulating Trans-Ingur/I Economic Relations Views from Two Banks

RegUlating tRans-ingUR/i economic Relations Views fRom two Banks July 2011 Understanding conflict. Building peace. this initiative is funded by the european union about international alert international alert is a 25-year-old independent peacebuilding organisation. We work with people who are directly affected by violent conflict to improve their prospects of peace. and we seek to influence the policies and ways of working of governments, international organisations like the un and multinational companies, to reduce conflict risk and increase the prospects of peace. We work in africa, several parts of asia, the south Caucasus, the Middle east and Latin america and have recently started work in the uK. our policy work focuses on several key themes that influence prospects for peace and security – the economy, climate change, gender, the role of international institutions, the impact of development aid, and the effect of good and bad governance. We are one of the world’s leading peacebuilding nGos with more than 155 staff based in London and 15 field offices. to learn more about how and where we work, visit www.international-alert.org. this publication has been made possible with the help of the uK Conflict pool and the european union instrument of stability. its contents are the sole responsibility of international alert and can in no way be regarded as reflecting the point of view of the european union or the uK government. © international alert 2011 all rights reserved. no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. -

Abkhazia: Deepening Dependence

ABKHAZIA: DEEPENING DEPENDENCE Europe Report N°202 – 26 February 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. RECOGNITION’S TANGIBLE EFFECTS ................................................................... 2 A. RUSSIA’S POST-2008 WAR MILITARY BUILD-UP IN ABKHAZIA ...................................................3 B. ECONOMIC ASPECTS ....................................................................................................................5 1. Dependence on Russian financial aid and investment .................................................................5 2. Tourism potential.........................................................................................................................6 3. The 2014 Sochi Olympics............................................................................................................7 III. LIFE IN ABKHAZIA........................................................................................................ 8 A. POPULATION AND CITIZENS .........................................................................................................8 B. THE 2009 PRESIDENTIAL POLL ..................................................................................................10 C. EXTERNAL RELATIONS ..............................................................................................................11 -

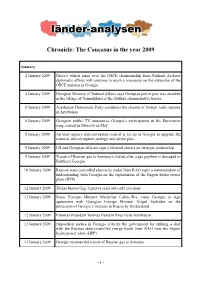

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

Abkhazia to Be Included in Even More Distant

caucasus analytical caucasus analytical digest 07/09 digest rity? Which flexible arrangements are conceivable for zia, whether in the framework of a common state or the issuing of visas for Abkhaz holders of Georgian as two cooperating independent states, have become passports that would allow Abkhazia to be included in even more distant. The same is true to an even greater European education and exchange programs? extent for the possible integration of both into a “polit- Which measures would allow the EU to enhance ical Europe” expanded to include the Black Sea region. the efficiency of its necessary long-term engagement on Nevertheless, that seems to be the only alternative to the behalf of political and legal reforms in Georgia? The suc- development that currently seems to be the most likely cess of these reforms is a precondition for the country’s one, namely a factual annexation of the small Abkhaz peaceful domestic consolidation and thus also for greater state by Russia in a Southern Caucasus that will likely flexibility towards the secessionist republics. be afflicted by geopolitical confrontation and instabil- Since the events of August 2008, the prospects of ity for a long time to come. peaceful reconciliation between Georgia and Abkha- Translated from German by Christopher Findlay About the Author Walter Kaufmann is an independent analyst and the former director (2002–2008) of the Heinrich Böll Foundation South Caucasus. Opinion Georgia’s Relationship with Abkhazia By Paata Zakareisvili, Tbilisi Abstract The August 2008 conflict between Georgia and Russia fundamentally changed the situation regarding the separatist territories in Georgia, fundamentally strengthening Russia’s position. -

An Ambivalent 'Independence'

OswcOMMentary issue 34 | 20.01.2010 | ceNTRe fOR eAsTeRN sTudies An ambivalent ‘independence’ Abkhazia, an unrecognised democracy under Russian protection NTARy Wojciech Górecki Me ces cOM Abkhazia – a state unrecognised by the international community and depen- dent on Russia – has features of a democracy, including political pluralism. This is manifested through regularly held elections, which are a time of ge- tudies nuine competition between candidates, and through a wide range of media, s including the pro-opposition private TV station Abaza. astern e The competing political forces have different visions for the republic’s deve- lopment. President Sergei Bagapsh’s team would like to build up multilateral foreign relations (although the highest priority would be given to relations 1 Despite the lack of with Russia), while the group led by Raul Khajimba, a former vice-president international recognition, entre for it seems unreasonable c and present leader of the opposition, would rather adopt a clear pro-Moscow to use the form ‘self- orientation. It is worth noting that neither of the significant political forces appointed’ or ‘so-called’ president, or to append wants Abkhazia to become part of Russia (while such proposals have been inverted commas to the term (which also con- made in South Ossetia), and a majority of the Abkhazian elite sees Russia’s NTARy cerns other Abkhazian recognition of the country’s independence as a Pyrrhic victory because Me officials and institutions) it has limited their country’s room for manoeuvre. However, all parties are because Bagapsh in fact performs this agreed in ruling out any future dependence on Georgia. -

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2014

Chronicle: The Caucasus In the Year 2014 January 1 January 2014 The Georgian State Ministry for Reintegration is renamed into State Ministry for Reconciliation and Civic Equality in a move that Tbilisi officials say will help engagement with the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia 4 January 2014 Russia pledges over 180 million dollars to the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2014–2016 through a decree signed by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev with the financial aid to be provided via the Russian Ministry of Construction 14 January 2014 Hungary becomes the twelfth country to recognize Georgia’s neutral travel documents designed for residents of the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia 16 January 2014 Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili says that Russia lacks the levers to deter the country’s signing of an Association Agreement with the European Union although provocations are expected 20 January 2014 Georgian President Giorgi Margvelashvili meets with his Turkish counterpart Abdullah Gül and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during a visit to Turkey that includes meetings with representatives of the Georgian diaspora 30 January 2014 Czech President Milos Zeman says during Armenian President Serzh Sarkisian’s official visit to Prague that the mass killings of Armenians during the Ottoman empire amounted to a “genocide” February 3 February 2014 Azerbaijani parliament speaker Oqtay Asadov calls on religious clerics to perform prayers in Azeri and not in Arabic to make it easier for people to -

Opening the Russian–Georgian Railway Link Through Abkhazia

CORE POLICY BRIEF 05 2013 Visiting Address: Hausmanns gate 7 gate Hausmanns Address: Visiting NO Grønland, 9229 PO Box (PRIO) Oslo Institute Research Peace Opening the Russian– Georgian railway link - 0134 Oslo, Norway Oslo, 0134 through Abkhazia A challenging Georgian governance initiative [email protected] www.projectcore.eu (CORE) India and Europe in Resolution Conflict and Governance of Cultures Soon after the parliamentary elec- Key Questions tion in 2012 Georgia’s new gov- ernment declared its willingness to How important is the restoration of the railway link for Georgia and Abkha- reconstruct and reopen the former zia, and particularly for the purpose of railway communication link with conflict resolution between the two? Russia through Abkhazia, which What are the political risks involved in the railway project? ISBN: ISBN: www.prio.no was interrupted as a result of the Does the new initiative meet the in- 978 978 Georgian–Abkhaz war in 1993. terests of all countries in the Caucasus - - 82 82 - - With its confidence-building charac- 7288 7288 region? - - 515 516 ter, the initiative is part of a broader - - 0 7 (print) Georgian foreign policy strategy aimed at re-establishing political and (online) economic relations with Russia, a development that would represent a significant geopolitical challenge for the countries of the South Cauca- sus. The initiative will test Tbilisi’s ability to prevent any changes to Abkhazia’s current political status and to keep the project purely eco- nomic in nature. Nona Mikhelidze Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) Opening the railway: A confidence- building measure The victory of Bidzina Ivanishvili’s coalition in the 2012 parliamentary elections in Georgia has brought about a fundamental change to the Georgian–Abkhaz peace process. -

Pdf | 267.83 Kb

Georgia | No 3 | June to July 2007 GEORGIA | Trends in Conflict and Cooperation The period under review was mostly dominated by the up and down of Russian-Georgian relations. After a bilateral meeting between President Putin and President Saakshvili in St. Petersburg on 9 June, a slight stabilization appeared in bilateral relations. Russia – still Georgia’s second largest trading partner – seemed to be easing the pressure on Russian-Georgian relations not only because of the WTO accession plan, but also because of the Olympic Winter Games to be held in Sochi in 2014. But this improvement in Russian-Georgian relations did not suit everyone, especially not separatist parties, which may be one of the reasons why in June “unknown persons” fired several times Country Stability and Conflictive Events in South Ossetia on Georgian and South Ossetian villages. As can be seen on the graph, additional tensions grew in summer paralleling the water shortage problem in the Tskhinvali region, which happens every summer since 2004. As usual, political figures in Russia and in the unrecognized republics immediately expressed concern that the escalation of tensions in the conflict zone signalizes a new Georgian attempt to restore its hegemony over South Ossetia by force of arms. Relations between Georgia and Russia worsened further after the publication of the last UNOMIG report issued on 12 July. The report suggested, but did not explicitly claim, that Russian army helicopters could have been involved in an attack on Tbilisi- controlled upper Kodori Gorge on 11 March 2007. Soon after, the Russian Foreign Source: FAST event data Ministry stated that “it is clear which side has been interested in the incident. -

Como Exportar Geórgia

Como Exportar Geórgia entre Ministério das Relações Exteriores Departamento de Promoção Comercial e Investimentos Divisão de Informação Comercial Como Exportar Geórgia Sumário SUMÁRIO VI – ESTRUTURA DE COMÉRCIO............................50 1..Canais.de.distribuição.......................................... 50 INTRODUÇÃO.........................................................2 2..Promoção.de.vendas............................................ 53 MAPA......................................................................3 3..Práticas.comerciais.............................................. 55 DADOS BÁSICOS.....................................................4 VII - RECOMENDAÇÕES ÀS EMPRESAS BRASILEIRAS 60 I – ASPECTOS GERAIS............................................5 1. Geografia.............................................................5 ANEXOS................................................................62 2..População.............................................................6 I.–.ENDEREÇOS...................................................... 62 3..Transportes.e.comunicações.................................. 12 II.–.TRANSPORTES.E.COMUNICAÇÕES.COM. 4..Estrutura.política.e.administrativa.......................... 15 .......O.BRASIL........................................................ 79 5..Participação.em.organizações.internacionais............ 18 III.–.INFORMAÇÕES.SOBRE.SGP............................... 79 IV.–.INFORMAÇÕES.PRÁTICAS.................................. 80 II – ECONOMIA, MOEDA E FINANÇAS...................20 1..Perspectiva.econômica........................................ -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA January 27-29 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: January 30, 2020 Occupied Regions Abkhazia Region 1. Aslan Bzhania to run in so-called presidential elections in occupied Abkhazia Aslan Bzhania, Leader of the occupied Abkhazia region of Georgia will participate in the so-called elections of Abkhazia. Bzhania said that the situation required unification in a team that he would lead. So-called presidential elections in occupied Abkhazia are scheduled for March 22. Former de-facto President of Abkhazia Raul Khajimba quit post amid the ongoing protest rallies. The opposition demanded his resignation. The Cassation Collegiums of Judges declared results of the September 8, 2019, presidential elections as null and void (1TV, January 28, 2020). Foreign Affairs 2. EU Special Representative Klaar Concludes Georgia Visit Toivo Klaar, the European Union Special Representative for the South Caucasus and the crisis in Georgia, who visited Tbilisi on January 20-25, held bilateral consultations with Georgian leaders. Spokesperson to the EU Special Representative Klaar told Civil.ge that this visit aimed to discuss the current situation in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia, as well as ―continuing security and humanitarian challenges on the ground,‖ in particular in the context of the Tskhinvali crossing points, which ―remain closed and security concerns are still significant.‖ Several issues discussed during the last round of the Geneva International Discussions (GID), which was held in December 2019, were also raised during his meetings. ―This visit allows him to get a better understanding of the Georgian position as well as to pass key messages to his interlocutors,‖ Toivo Klaar‘s Spokesperson told Civil.ge earlier last week (Civil.ge, January 27, 2020).