Sustainability Indicators for Tasmanian Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

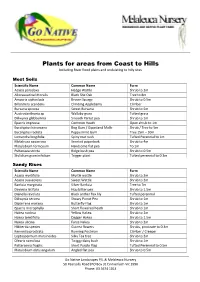

Plants for Areas from Coast to Hills Including River Flood Plains and Undulating to Hilly Sites

Plants for areas from Coast to Hills Including River flood plains and undulating to hilly sites Most Soils Scientific Name Common Name Form Acacia paradoxa Hedge Wattle Shrub to 2m Allocasuarina littoralis Black She Oak Tree to 8m Amperia xiphoclada Broom Spurge Shrub to 0.5m Billardiera scandens Climbing Appleberry Climber Bursaria spinosa Sweet Bursaria Shrub to 5m Austrodanthonia sp Wallaby grass Tufted grass Dillwynia glabberima Smooth Parrot pea Shrub to 1m Epacris impressa Common Heath Open shrub to 1m Eucalyptus kitsoniana Bog Gum / Gippsland Malle Shrub / Tree to 5m Eucalyptus radiata Peppermint Gum Tree 15m – 30m Lomandra longifolia Spiny mat rush Tufted Perennial to 1m Melaleuca squarrosa Scented paperbark Shrub to 4m Platylobium formosum Handsome flat pea To 1m Pultenaea stricta Ridge bush pea Shrub to 0.5m Stylidium graminifolium Trigger plant Tufted perennial to 0.3m Sandy Rises Scientific Name Common Name Form Acacia myrtifolia Myrtle wattle Shrub to 2m Acacia suaveolens Sweet Wattle Shrub to 2m Banksia marginata Silver Banksia Tree to 7m Daviesia latifolia Hop bitter pea Shrub to 1.5m Dianella revoluta Black anther flax lily Tufted perennial Dillwynia sericea Showy Parrot Pea Shrub to 1m Diplarrena moraea Butterfly Flag Shrub to 1m Epacris microphylla Short flowered heath Shrub to 1m Hakea nodosa Yellow Hakea Shrub to 2m Hakea teretifolia Dagger Hakea Shrub to 1.5m Hakea ulicina Furze Hakea Shrub to 2m Hibbertia species Guinea flowers Shrubs, prostrate to 0.3m Kennedia prostrata Running Postman Climber / Creeper Leptospermum -

Blue Tier Reserve Background Report 2016File

Background Report Blue Tier Reserve www.tasland.org.au Tasmanian Land Conservancy (2016). The Blue Tier Reserve Background Report. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Tasmania Australia. Copyright ©Tasmanian Land Conservancy The views expressed in this report are those of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy and not the Federal Government, State Government or any other entity. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquires concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Front Image: Myrtle rainforest on Blue Tier Reserve - Andy Townsend Contact Address Tasmanian Land Conservancy PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, 827 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay TAS 7005 | p: 03 6225 1399 | www.tasland.org.au Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 1 Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Location and Access ................................................................................................................................ 4 Bioregional Values and Reserve Status .................................................................................................. -

Winter Edition 2020 - 3 in This Issue: Office Bearers for 2017

1 Australian Plants Society Armidale & District Group PO Box 735 Armidale NSW 2350 web: www.austplants.com.au/Armidale e-mail: [email protected] Crowea exalata ssp magnifolia image by Maria Hitchcock Winter Edition 2020 - 3 In this issue: Office bearers for 2017 ......p1 Editorial …...p2Error! Bookmark not defined. New Website Arrangements .…..p3 Solstice Gathering ......p4 Passion, Boers & Hibiscus ......p5 Wollomombi Falls Lookout ......p7 Hard Yakka ......p8 Torrington & Gibraltar after fires ......p9 Small Eucalypts ......p12 Drought tolerance of plants ......p15 Armidale & District Group PO Box 735, Armidale NSW 2350 President: Vacant Vice President: Colin Wilson Secretary: Penelope Sinclair Ph. 6771 5639 [email protected] Treasurer: Phil Rose Ph. 6775 3767 [email protected] Membership: Phil Rose [email protected] 2 Markets in the Mall, Outings, OHS & Environmental Officer and Arboretum Coordinator: Patrick Laher Ph: 0427327719 [email protected] Newsletter Editor: John Nevin Ph: 6775218 [email protected],net.au Meet and Greet: Lee Horsley Ph: 0421381157 [email protected] Afternoon tea: Deidre Waters Ph: 67753754 [email protected] Web Master: Eric Sinclair Our website: http://www.austplants.com.au From the Editor: We have certainly had a memorable year - the worst drought in living memory followed by the most extensive bushfires seen in Australia, and to top it off, the biggest pandemic the world has seen in 100 years. The pandemic has made essential self distancing and quarantining to arrest the spread of the Corona virus. As a result, most APS activities have been shelved for the time being. Being in isolation at home has been a mixed blessing. -

A Taxonomic Revision of Hymenophyllaceae

BLUMEA 51: 221–280 Published on 27 July 2006 http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/000651906X622210 A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF HYMENOPHYLLACEAE ATSUSHI EBIHARA1, 2, JEAN-YVES DUBUISSON3, KUNIO IWATSUKI4, SABINE HENNEQUIN3 & MOTOMI ITO1 SUMMARY A new classification of Hymenophyllaceae, consisting of nine genera (Hymenophyllum, Didymoglos- sum, Crepidomanes, Polyphlebium, Vandenboschia, Abrodictyum, Trichomanes, Cephalomanes and Callistopteris) is proposed. Every genus, subgenus and section chiefly corresponds to the mono- phyletic group elucidated in molecular phylogenetic analyses based on chloroplast sequences. Brief descriptions and keys to the higher taxa are given, and their representative members are enumerated, including some new combinations. Key words: filmy ferns, Hymenophyllaceae, Hymenophyllum, Trichomanes. INTRODUCTION The Hymenophyllaceae, or ‘filmy ferns’, is the largest basal family of leptosporangiate ferns and comprises around 600 species (Iwatsuki, 1990). Members are easily distin- guished by their usually single-cell-thick laminae, and the monophyly of the family has not been questioned. The intrafamilial classification of the family, on the other hand, is highly controversial – several fundamentally different classifications are used by indi- vidual researchers and/or areas. Traditionally, only two genera – Hymenophyllum with bivalved involucres and Trichomanes with tubular involucres – have been recognized in this family. This scheme was expanded by Morton (1968) who hierarchically placed many subgenera, sections and subsections under -

PUBLISHER S Candolle Herbarium

Guide ERBARIUM H Candolle Herbarium Pamela Burns-Balogh ANDOLLE C Jardin Botanique, Geneva AIDC PUBLISHERP U R L 1 5H E R S S BRILLB RI LL Candolle Herbarium Jardin Botanique, Geneva Pamela Burns-Balogh Guide to the microform collection IDC number 800/2 M IDC1993 Compiler's Note The microfiche address, e.g. 120/13, refers to the fiche number and secondly to the individual photograph on each fiche arranged from left to right and from the top to the bottom row. Pamela Burns-Balogh Publisher's Note The microfiche publication of the Candolle Herbarium serves a dual purpose: the unique original plants are preserved for the future, and copies can be made available easily and cheaply for distribution to scholars and scientific institutes all over the world. The complete collection is available on 2842 microfiche (positive silver halide). The order number is 800/2. For prices of the complete collection or individual parts, please write to IDC Microform Publishers, P.O. Box 11205, 2301 EE Leiden, The Netherlands. THE DECANDOLLEPRODROMI HERBARIUM ALPHABETICAL INDEX Taxon Fiche Taxon Fiche Number Number -A- Acacia floribunda 421/2-3 Acacia glauca 424/14-15 Abatia sp. 213/18 Acacia guadalupensis 423/23 Abelia triflora 679/4 Acacia guianensis 422/5 Ablania guianensis 218/5 Acacia guilandinae 424/4 Abronia arenaria 2215/6-7 Acacia gummifera 421/15 Abroniamellifera 2215/5 Acacia haematomma 421/23 Abronia umbellata 221.5/3-4 Acacia haematoxylon 423/11 Abrotanella emarginata 1035/2 Acaciahastulata 418/5 Abrus precatorius 403/14 Acacia hebeclada 423/2-3 Acacia abietina 420/16 Acacia heterophylla 419/17-19 Acacia acanthocarpa 423/16-17 Acaciahispidissima 421/22 Acacia alata 418/3 Acacia hispidula 419/2 Acacia albida 422/17 Acacia horrida 422/18-20 Acacia amara 425/11 Acacia in....? 423/24 Acacia amoena 419/20 Acacia intertexta 421/9 Acacia anceps 419/5 Acacia julibross. -

Visitor Learning Guide

VISITOR LEARNING GUIDE 1 Produced by The Wilderness Society The Styx Valley of the Giants oers the opportunity to experience one of the world’s most iconic and spectacular forest areas. For decades the Wilderness Society has worked with the broader community to achieve protection for the Styx and we want to share it, and some of its stories, with you. This guide is not meant to be a comprehensive overview of the Styx, Tasmania’s forests or World Heritage. Rather, it is designed to share a cross-section of knowledge through simple stories that follow a common theme on each of the identified walks. With its help, we hope you will learn from this spectacular place, and leave knowing more about our forests, their natural and cultural legacy and some other interesting titbits. The Wilderness Society acknowledges the Tasmanian Aboriginal community as the traditional owners and custodians of all Country in Tasmania and pays respect to Elders past and present. We support eorts to progress reconciliation, land justice and equality. We recognise and welcome actions that seek to better identify, present, protect and conserve Aboriginal cultural heritage, irrespective of where it is located. Cover photo: A giant eucalypt in the Styx Valley, Rob Blakers. © The Wilderness Society, Tasmania 2015. STYX VALLEY OF THE GIANTS - VISITOR LEARNING GUIDE TO ELLENDALE MT FIELD FENTONBURY NATIONAL PARK WESTERWAY B61 TYENNA Tyenna River TO NEW NORFOLK TO LAKE PEDDER & HOBART & STRATHGORDON MAYDENA FOOD & ACCOMMODATION There’s some great accommodation and food options on your way to the Styx. Westerway • Blue Wren Riverside Cottage • Duy’s Country Accommodation Styx River • Platypus Playground Riverside Cottage Styx River . -

Australian Native Plants Society Australia Hakea

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY AUSTRALIA HAKEA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER No. 65 OCTOBER 2017 ISSN0727- 7008 Leader: Paul Kennedy 210 Aireys Street Elliminyt Vic. 3250 E mail [email protected] Tel. 03-52315569 Dear members. We have had a very cold winter and now as spring emerges the cold remains with very wet conditions. Oh how I long for some warm sunshine to brighten our day. However the Hakeas have stood up to the cold weather very well and many have now flowered. Rainfall in August was 30mm but in the first 6 days of September another 56mm was recorded making the soil very moist indeed. The rain kept falling in September with 150mm recorded. Fortunately my drainage work of spoon drains and deeper drains with slotted pipe with blue metal cover on top shed a lot of water straight into the Council drains. Most of the Hakeas like well drained conditions, so building up beds and getting rid of excess water will help in making them survive. The collection here now stands at 162 species out of a possible 169. Seed of some of the remaining species hopefully will arrive here before Christmas so that I can propagate them over summer. Wanderings. Barbara and I spent most of June and July in northern NSW and Queensland to escape the cold conditions down here. I did look around for Hakeas and visited some members’ gardens. Just to the east of Cann River I found Hakea decurrens ssp. physocarpa, Hakea ulicina and Hakea teretifolia ssp. hirsuta all growing on the edge of a swamp. -

Lssn 0811-5311 DATE - SEPTEMBER 19 87

lSSN 0811-5311 DATE - SEPTEMBER 19 87 "REGISTERD BY AUSTRALIA POST -, FTlBL IC AT ION LEADER : Peter Hind, 41 Miller stredt, Mt. Druitt 2770 SECRETARY : Moreen Woollett, 3 Curriwang Place, Como West 2226 HON. TREASURER: Margaret Olde, 138 Fmler ~oad,Illaong 2234 SPORE BANK: Jenny Thompson, 2a Albion blace, Engadine 2233 Dear Wers, I First the good ws. I ?hanks to the myme&- who pdded articles, umrmts and slides, the book uhichwe are produehg thraqh the Pblisw Secticm of S.G.A.P. (NSFi) wted is nearing c~np3etion. mjblicatio~lshkmger, Bill Payne has proof copies and is currm'tly lt-dhg firral co-m. !€his uill be *e initial. volume in ghat is expeckd to be a -1ete reference to &~~txalirrnferns and is titled "The Australian Fern Series 1". It is only a smll volm~hi&hcrpefully can be retailed at an afford& le price -b the majority of fern grcw ers. Our prl3 Emtion differs -Em maq rrgard&gr' b mks b-use it is not full of irrelevant padding, me -is has been on pm3uci.q a practical guide to tihe cultivation of particular Aus&dlian native ferns, There is me article of a technical nature based rm recent research, but al-h scientific this tm has been x ritten in simple tmm that would be appreciated by most fern grm ers, A feature of the beis the 1- nuher of striking full =lour Uus.hratims. In our next Wsletterge hope to say more &opt details of phlicatim EOODIA SP . NO. 1 - CANIF On the last page of this Newsletter there is d photo copy of another unsual and apparently attractive fern contributed by Queensland member Rod Pattison. -

East Gippsland, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

A Review of Natural Values Within the 2013 Extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Nature Conservation Report 2017/6 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Hobart A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Jayne Balmer, Jason Bradbury, Karen Richards, Tim Rudman, Micah Visoiu, Shannon Troy and Naomi Lawrence. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, September 2017 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (World Heritage Program). Australian Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Tasmanian or Australian Governments. ISSN 1441-0680 Copyright 2017 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Published by Natural Values Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart, Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph of Eucalyptus regnans tall forest in the Styx Valley: Rob Blakers Cite as: Balmer, J., Bradbury, J., Richards, K., Rudman, T., Visoiu, M., Troy, S. and Lawrence, N. 2017. A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. -

Phylogeny, Character Evolution and the Systematics of Psilochilus (Triphoreae)

THE PRIMITIVE EPIDENDROIDEAE (ORCHIDACEAE): PHYLOGENY, CHARACTER EVOLUTION AND THE SYSTEMATICS OF PSILOCHILUS (TRIPHOREAE) A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Erik Paul Rothacker, M.Sc. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Doctoral Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. John V. Freudenstein, Adviser Dr. John Wenzel ________________________________ Dr. Andrea Wolfe Adviser Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology Graduate Program COPYRIGHT ERIK PAUL ROTHACKER 2007 ABSTRACT Considering the significance of the basal Epidendroideae in understanding patterns of morphological evolution within the subfamily, it is surprising that no fully resolved hypothesis of historical relationships has been presented for these orchids. This is the first study to improve both taxon and character sampling. The phylogenetic study of the basal Epidendroideae consisted of two components, molecular and morphological. A molecular phylogeny using three loci representing each of the plant genomes including gap characters is presented for the basal Epidendroideae. Here we find Neottieae sister to Palmorchis at the base of the Epidendroideae, followed by Triphoreae. Tropidieae and Sobralieae form a clade, however the relationship between these, Nervilieae and the advanced Epidendroids has not been resolved. A morphological matrix of 40 taxa and 30 characters was constructed and a phylogenetic analysis was performed. The results support many of the traditional views of tribal composition, but do not fully resolve relationships among many of the tribes. A robust hypothesis of relationships is presented based on the results of a total evidence analysis using three molecular loci, gap characters and morphology. Palmorchis is placed at the base of the tree, sister to Neottieae, followed successively by Triphoreae sister to Epipogium, then Sobralieae. -

ACT, Australian Capital Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations.