Plantaginaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Edition 2020 - 3 in This Issue: Office Bearers for 2017

1 Australian Plants Society Armidale & District Group PO Box 735 Armidale NSW 2350 web: www.austplants.com.au/Armidale e-mail: [email protected] Crowea exalata ssp magnifolia image by Maria Hitchcock Winter Edition 2020 - 3 In this issue: Office bearers for 2017 ......p1 Editorial …...p2Error! Bookmark not defined. New Website Arrangements .…..p3 Solstice Gathering ......p4 Passion, Boers & Hibiscus ......p5 Wollomombi Falls Lookout ......p7 Hard Yakka ......p8 Torrington & Gibraltar after fires ......p9 Small Eucalypts ......p12 Drought tolerance of plants ......p15 Armidale & District Group PO Box 735, Armidale NSW 2350 President: Vacant Vice President: Colin Wilson Secretary: Penelope Sinclair Ph. 6771 5639 [email protected] Treasurer: Phil Rose Ph. 6775 3767 [email protected] Membership: Phil Rose [email protected] 2 Markets in the Mall, Outings, OHS & Environmental Officer and Arboretum Coordinator: Patrick Laher Ph: 0427327719 [email protected] Newsletter Editor: John Nevin Ph: 6775218 [email protected],net.au Meet and Greet: Lee Horsley Ph: 0421381157 [email protected] Afternoon tea: Deidre Waters Ph: 67753754 [email protected] Web Master: Eric Sinclair Our website: http://www.austplants.com.au From the Editor: We have certainly had a memorable year - the worst drought in living memory followed by the most extensive bushfires seen in Australia, and to top it off, the biggest pandemic the world has seen in 100 years. The pandemic has made essential self distancing and quarantining to arrest the spread of the Corona virus. As a result, most APS activities have been shelved for the time being. Being in isolation at home has been a mixed blessing. -

Indigenous Plants of Bendigo

Produced by Indigenous Plants of Bendigo Indigenous Plants of Bendigo PMS 1807 RED PMS 432 GREY PMS 142 GOLD A Gardener’s Guide to Growing and Protecting Local Plants 3rd Edition 9 © Copyright City of Greater Bendigo and Bendigo Native Plant Group Inc. This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the City of Greater Bendigo. First Published 2004 Second Edition 2007 Third Edition 2013 Printed by Bendigo Modern Press: www.bmp.com.au This book is also available on the City of Greater Bendigo website: www.bendigo.vic.gov.au Printed on 100% recycled paper. Disclaimer “The information contained in this publication is of a general nature only. This publication is not intended to provide a definitive analysis, or discussion, on each issue canvassed. While the Committee/Council believes the information contained herein is correct, it does not accept any liability whatsoever/howsoever arising from reliance on this publication. Therefore, readers should make their own enquiries, and conduct their own investigations, concerning every issue canvassed herein.” Front cover - Clockwise from centre top: Bendigo Wax-flower (Pam Sheean), Hoary Sunray (Marilyn Sprague), Red Ironbark (Pam Sheean), Green Mallee (Anthony Sheean), Whirrakee Wattle (Anthony Sheean). Table of contents Acknowledgements ...............................................2 Foreword..........................................................3 Introduction.......................................................4 -

Morphological Evolution and Systematics of Synthyris and Besseya (Veronicaceae): a Phylogenetic Analysis

Systematic Botany (2004), 29(3): pp. 716±736 q Copyright 2004 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Morphological Evolution and Systematics of Synthyris and Besseya (Veronicaceae): A Phylogenetic Analysis LARRY HUFFORD2 and MICHELLE MCMAHON1 School of Biological Sciences, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington 99164-4236 1Present address: Section of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, University of California, Davis, California 95616 2Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Communicating Editor: Wendy B. Zomlefer ABSTRACT. Phylogenetic analyses are used to examine the morphological diversity and systematics of Synthyris and Besseya. The placement of Synthyris and Besseya in Veronicaceae is strongly supported in parsimony analyses of nuclear ribosomal ITS DNA sequences. Parsimony and maximum likelihood (ML) criteria provide consistent hypotheses of clades of Synthyris and Besseya based on the ITS data. The combination of morphological characters and ITS data resolve additional clades of Synthyris and Besseya. The results show that Synthyris is paraphyletic to Besseya. In the monophyletic Synthyris clade, Besseya forms part of a Northwest clade that also includes the alpine S. canbyi, S. dissecta,andS. lanuginosa and mesic forest S. cordata, S. reniformis, S. platycarpa,andS. schizantha. The Northwest clade is the sister of S. borealis. An Intermountain clade, comprising S. ranunculina, S. laciniata, S. pinnati®da,andS. missurica, is the sister to the rest of the Synthyris clade. Constraint topologies are used to test prior hypotheses of relationships and morphological similarities. Parametric bootstrapping is used to compare the likelihood values of the best trees obtained in searches under constraints to that of the best tree found without constraints. -

ACT, Australian Capital Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Australian Native Plants Society Canberra

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SOCIETY CANBERRA REGION (INC) Journal Vol. 19 No. 10 June 2019 ISN 1447-1507 Print Post Approved PP100000849 Contents President's Report Ben Walcott 1 President's Report Meritorious Awards Ben Walcott 2 Rwsupinate or non-resupinate Roger Farrow 3 Foliage in the Garden Ben Walcott 9 By Ben Walcott ones have been available to members. At the recent Conference in Tasmania ANPSA News Ritta Boevink 13 I would like to thank all those volunteers last year, it was agreed that over time ACRA, PBR & the Vexed Issue of Cultivar Registration Lindal Thorburn 15 who came to help setup the plant sale regional societies would distribute their Whn Adriana meets Adrian Roger Farrow 25 on Friday and the sale on Saturday in journal electronically rather than in Neonicotinoid Pesticides ANPSC Council 29 March. Everything went smoothly and printed form. Wildflowers of the Victorian Alpine areas John Murphy 31 we had a very successful sale. We had Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia Forgotten Plants of the ACT — A Pictorial Guide Roger Farrow 38 about 12,500 plants on the ground and have already stopped sending us paper Study Group Notes Brigitta Wimmer 50 85% of them were sold which is a very good result for an autumn sale. copies and now send us electronic files. ANPS Canberra contacts and membership details inside back cover These journals will be loaded into the Thanks particularly to Linda Tabe who is Members Area of our website under the new Plant Sale Coordinator and to ‘Journals’ so that all members can read Cover: Banksia grandis shoots; Photo: Glenn Pure Anne Campbell who did the publicity them. -

Trees, Shrubs, and Perennials That Intrigue Me (Gymnosperms First

Big-picture, evolutionary view of trees and shrubs (and a few of my favorite herbaceous perennials), ver. 2007-11-04 Descriptions of the trees and shrubs taken (stolen!!!) from online sources, from my own observations in and around Greenwood Lake, NY, and from these books: • Dirr’s Hardy Trees and Shrubs, Michael A. Dirr, Timber Press, © 1997 • Trees of North America (Golden field guide), C. Frank Brockman, St. Martin’s Press, © 2001 • Smithsonian Handbooks, Trees, Allen J. Coombes, Dorling Kindersley, © 2002 • Native Trees for North American Landscapes, Guy Sternberg with Jim Wilson, Timber Press, © 2004 • Complete Trees, Shrubs, and Hedges, Jacqueline Hériteau, © 2006 They are generally listed from most ancient to most recently evolved. (I’m not sure if this is true for the rosids and asterids, starting on page 30. I just listed them in the same order as Angiosperm Phylogeny Group II.) This document started out as my personal landscaping plan and morphed into something almost unwieldy and phantasmagorical. Key to symbols and colored text: Checkboxes indicate species and/or cultivars that I want. Checkmarks indicate those that I have (or that one of my neighbors has). Text in blue indicates shrub or hedge. (Unfinished task – there is no text in blue other than this text right here.) Text in red indicates that the species or cultivar is undesirable: • Out of range climatically (either wrong zone, or won’t do well because of differences in moisture or seasons, even though it is in the “right” zone). • Will grow too tall or wide and simply won’t fit well on my property. -

Lamiales – Synoptical Classification Vers

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.6.2 (in prog.) Updated: 12 April, 2016 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.6.2 (This is a working document) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, P. Beardsley, D. Bedigian, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, J. Chau, J. L. Clark, B. Drew, P. Garnock- Jones, S. Grose (Heydler), R. Harley, H.-D. Ihlenfeldt, B. Li, L. Lohmann, S. Mathews, L. McDade, K. Müller, E. Norman, N. O’Leary, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, D. Tank, E. Tripp, S. Wagstaff, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, A. Wortley, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and many others [estimated 25 families, 1041 genera, and ca. 21,878 species in Lamiales] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near- term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. -

Report on the Grimwade Plant Collection of Percival St John and Botanical Exploration of Mt Buffalo National Park (Victoria, Australia)

Report on the Grimwade Plant Collection of Percival St John and Botanical Exploration of Mt Buffalo National Park (Victoria, Australia) Alison Kellow Michael Bayly Pauline Ladiges School of Botany, The University of Melbourne July, 2007 THE GRIMWADE PLANT COLLECTION, MT BUFFALO Contents Summary ...........................................................................................................................3 Mt Buffalo and its flora.....................................................................................................4 History of botanical exploration........................................................................................5 The Grimwade plant collection of Percival St John..........................................................8 A new collection of plants from Mt Buffalo - The Miegunyah Plant Collection (2006/2007) ....................................................................................................................................13 Plant species list for Mt Buffalo National Park...............................................................18 Conclusion.......................................................................................................................19 Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................19 References .......................................................................................................................20 Appendix 1 Details of specimens in the Grimwade Plant Collection.............................22 -

Thomas Coulter's Californian Exsiccata

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 37 Issue 1 Issue 1–2 Article 2 2019 Plantae Coulterianae: Thomas Coulter’s Californian Exsiccata Gary D. Wallace California Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Gary D. (2020) "Plantae Coulterianae: Thomas Coulter’s Californian Exsiccata," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 37: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol37/iss1/2 Aliso, 37(1–2), pp. 1–73 ISSN: 0065-6275 (print), 2327-2929 (online) PLANTAE COULTERIANAE: THOMAS COULTER’S CALIFORNIAN EXSICCATA Gary D. Wallace California Botanic Garden [formerly Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden], 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711 ([email protected]) abstract An account of the extent, diversity, and importance of the Californian collections of Thomas Coulter in the herbarium (TCD) of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, is presented here. It is based on examination of collections in TCD, several other collections available online, and referenced literature. Additional infor- mation on historical context, content of herbarium labels and annotations is included. Coulter’s collections in TCD are less well known than partial duplicate sets at other herbaria. He was the first botanist to cross the desert of southern California to the Colorado River. Coulter’s collections in TCD include not only 60 vascular plant specimens previously unidentified as type material but also among the first moss andmarine algae specimens known to be collected in California. A list of taxa named for Thomas Coulter is included. -

Flora-Lab-Manual.Pdf

LabLab MManualanual ttoo tthehe Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros Flora of New Mexico Lab Manual to the Flora of New Mexico Jane Mygatt Juliana Medeiros University of New Mexico Herbarium Museum of Southwestern Biology MSC03 2020 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM, USA 87131-0001 October 2009 Contents page Introduction VI Acknowledgments VI Seed Plant Phylogeny 1 Timeline for the Evolution of Seed Plants 2 Non-fl owering Seed Plants 3 Order Gnetales Ephedraceae 4 Order (ungrouped) The Conifers Cupressaceae 5 Pinaceae 8 Field Trips 13 Sandia Crest 14 Las Huertas Canyon 20 Sevilleta 24 West Mesa 30 Rio Grande Bosque 34 Flowering Seed Plants- The Monocots 40 Order Alistmatales Lemnaceae 41 Order Asparagales Iridaceae 42 Orchidaceae 43 Order Commelinales Commelinaceae 45 Order Liliales Liliaceae 46 Order Poales Cyperaceae 47 Juncaceae 49 Poaceae 50 Typhaceae 53 Flowering Seed Plants- The Eudicots 54 Order (ungrouped) Nymphaeaceae 55 Order Proteales Platanaceae 56 Order Ranunculales Berberidaceae 57 Papaveraceae 58 Ranunculaceae 59 III page Core Eudicots 61 Saxifragales Crassulaceae 62 Saxifragaceae 63 Rosids Order Zygophyllales Zygophyllaceae 64 Rosid I Order Cucurbitales Cucurbitaceae 65 Order Fabales Fabaceae 66 Order Fagales Betulaceae 69 Fagaceae 70 Juglandaceae 71 Order Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae 72 Linaceae 73 Salicaceae 74 Violaceae 75 Order Rosales Elaeagnaceae 76 Rosaceae 77 Ulmaceae 81 Rosid II Order Brassicales Brassicaceae 82 Capparaceae 84 Order Geraniales Geraniaceae 85 Order Malvales Malvaceae 86 Order Myrtales Onagraceae -

Keilor Plains Group MEETINGS First Friday of the Month (Not January) at 8Pm, Uniting Church Hall, Corner Roberts Road & Glenys Avenue, Airport West

AUSTRALIAN PLANTS SOCIETY (VICTORIA) KEILOR PLAINS GROUP MEETINGS First Friday of the month (not January) at 8pm, Uniting Church hall, corner Roberts Road & Glenys Avenue, Airport West. Autumn/winter 2016 NUMBER 129 June 3 APSKP meeting: Louise Pelle (landscape architect of King Billy Retreat, Rushworth) on “Garden Design with Indigenous Plants”. July 1 APSKP AGM + meeting: Yvonne Bischofberger (APSKP member & secretary of Friends of Newells Paddock) will update members on the amazing progress being made at Newells Paddock Urban Nature Reserve. August 5 APSKP meeting: Speaker to be confirmed. September 4 APSKP meeting: Chris Nicholson (APSKP member and head gardener, Royal Park, Parkville) will speak on the Australian Native Garden in Royal Park. October 5 APSKP meeting: Plant table; bring along cuttings from your garden to celbrate the mass of colour and form that is spring. November 4 APSKP meeting: Director and head of research at Currency Creek Arboretum, SA, Dean Nicolle will talk on “Eucalypts”. December 2 APSKP meeting: Christmas break up 1 The view from the courtyard Under the Eaves President Jason Caruso wins some and loses some Think nothing grows there? John Upsher says think again n the last newsletter, I was waiting there in an attempt to get hose conditions, under the wide delicate species and some of the more (with bated breath) for flower buds on a them through the summer eaves of a house, on the north facing showy and spectacular species. potted Eucalyptus rameliana to open. and to my surprise, they side with full sun all day and only In a neighbour’s garden in Maribyrnong IA few days before Christmas, the first have survived and showing T the least of rain that might get blown in, are I have these very conditions and have operculum dropped, revealing a stunning signs of ‘relief’ with the the best you could provide to grow some planted three species to try, alongside large flower. -

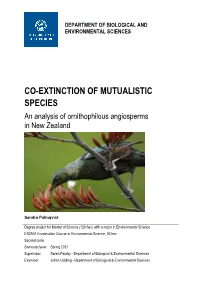

Co-Extinction of Mutualistic Species – an Analysis of Ornithophilous Angiosperms in New Zealand

DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES CO-EXTINCTION OF MUTUALISTIC SPECIES An analysis of ornithophilous angiosperms in New Zealand Sandra Palmqvist Degree project for Master of Science (120 hec) with a major in Environmental Science ES2500 Examination Course in Environmental Science, 30 hec Second cycle Semester/year: Spring 2021 Supervisor: Søren Faurby - Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences Examiner: Johan Uddling - Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences “Tui. Adult feeding on flax nectar, showing pollen rubbing onto forehead. Dunedin, December 2008. Image © Craig McKenzie by Craig McKenzie.” http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/sites/all/files/1200543Tui2.jpg Table of Contents Abstract: Co-extinction of mutualistic species – An analysis of ornithophilous angiosperms in New Zealand ..................................................................................................... 1 Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning: Samutrotning av mutualistiska arter – En analys av fågelpollinerade angiospermer i New Zealand ................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. Material and methods ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1 List of plant species, flower colours and conservation status ....................................... 7 2.1.1 Flower Colours .............................................................................................................