Downloaded From: Version: Accepted Version Publisher: Taylor & Francis DOI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commerce and Exchange Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary

Commerce and Exchange Buildings Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https:// www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of-selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide treats commercial buildings. These range from small local shops to huge department stores, from corner pubs to Victorian ‘gin palaces’, from simple sets of chambers to huge speculative office blocks. -

Management, Leadership and Leisure 12 - 15 Your Future 16-17 Entry Requirements 18

PLANNING AND MANCHESTER MANAGEMENT, GEOGRAPHY ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHITECTURE INSTITUTE OF LEADERSHIP SCHOOL SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT EDUCATION AND LEISURE OF LAW SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT, EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT UNDERGRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 Undergraduate Courses 2020 COURSES 2020 COURSES 2020 www.manchester.ac.uk/study-geography www.manchester.ac.uk/pem www.manchester.ac.uk/msa www.manchester.ac.uk/mie www.manchester.ac.uk/mll www.manchester.ac.uk www.manchester.ac.uk CHOOSE HY STUDY MANAGEMENT, MANCHESTER LEADERSHIPW AND LEISURE AT MANCHESTER? At Manchester, you’ll experience an education and environment that sets CONTENTS you on the right path to a professionally rewarding and personally fulfilling future. Choose Manchester and we’ll help you make your mark. Choose Manchester 2-3 Kai’s Manchester 4-5 Stellify 6-7 What the City has to offer 8-9 Applied Study Periods 10-11 Gain over 500 hours of industry experience through work-based placements Management, Leadership and Leisure 12 - 15 Your Future 16-17 Entry Requirements 18 Tailor your degree with options in sport, tourism and events management Broaden your horizons by gaining experience through UK-based or international work placements Develop skills valued within the global leisure industry, including learning a language via your free choice modules CHOOSE MANCHESTER 3 AFFLECK’S PALACE KAI’S Affleck’s is an iconic shopping emporium filled with unique independent traders selling everything from clothes, to records, to Pokémon cards! MANCHESTER It’s a truly fantastic environment with lots of interesting stuff, even to just window shop or get a coffee. -

MANCHESTER HIGH QUALITY WORK SPACE in MANCHESTER MANCHESTER CITY CENTRE St Ann’S Square Is One of Manchester’S Most Well Known and Busiest Public Squares

MANCHESTER HIGH QUALITY WORK SPACE IN MANCHESTER MANCHESTER CITY CENTRE St Ann’s Square is one of Manchester’s most well known and busiest public squares. The original heart of the retail district, it now contains a cosmopolitan mix of business, retail, residential and leisure, all in a historic open space that is now the emotional centre of Manchester and a treasured Conservation Area. St Ann’s House is an imposing 20th century building sympathetic to its setting. The brick and Portland stone façade offers classic lines, topped off by a striking green pantile mansard roof. The modern canopy frames the designer shops at ground floor level, whilst large windows on the upper floors offer gorgeous views overlooking the Church and Square and flood the space with light. HOUSE ANN’S ANN’S ST ST ST PETER’S MANCHESTER EXCHANGE SHUDEHILL SQUARE CENTRAL VICTORIA THE SQUARE TRANSPORT NORTHERN KING MANCHESTER METROLINK PICCADILLY CONVENTION STATION NOMA PRINTWORKS METROLINK INTERCHANGE QUARTER STREET TOWN HALL STATION STATION COMPLEX MANCHESTER HOUSE SALFORD LOWRY HARVEY ARNDALE SPINNINGFIELDS RADISSON THE CENTRAL HOTEL NICHOLS CENTRE BLU MIDLAND ANN’S STATION SELFRIDGES EDWARDIAN HOTEL ST & CO HOTEL It’s all here at St Ann’s Square — street flower 8 MINS WALK 15 MINS WALK stalls, visiting markets, Manchester’s third oldest Church, the iconic Royal Exchange MANCHESTER MANCHESTER with its celebrated Theatre, fashionable arcades and the city’s top jewellers. Statues MANCHESTER VICTORIA PICCADILLY and fountains go hand in hand with high MANCHESTER AN fashion retail, boutique hotels, traditional ale M GE VICTORIA ILLE L R ST ST REE RE T houses and trendy restaurants. -

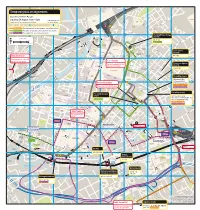

Enjoy Free Travel Around Manchester City Centre on a Free

Every 10 minutes Enjoy free travel around (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) Monday to Friday: 7am – 10pm GREEN free QUARTER bus Manchester city centre Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm Every 12 minutes Manchester Manchester Victoria on a free bus Sunday and public holidays: Arena 9:30am – 6pm Chetham’s VICTORIA STATION School of Music APPROACH Victoria Every 10 minutes GREENGATE Piccadilly Station Piccadilly Station (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) CHAPEL ST TODD NOMA Monday to Friday: 6:30am – 10pm ST VICTORIA MEDIEVAL BRIDGE ST National Whitworth Street Sackville Street Campus Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm QUARTER Chorlton Street The Gay Village Football Piccadilly Piccadilly Gardens River Irwell Cathedral Chatham Street Manchester Visitor Every 12 minutes Museum BAILEYNEW ST Information Centre Whitworth Street Palace Theatre Sunday and public holidays: Corn The India House 9:30am – 6pm Exchange Charlotte Street Manchester Art Gallery CHAPEL ST Salford WITHY GROVEPrintworks Chinatown Portico Library Central MARY’S MARKET Whitworth Street West MMU All Saints Campus Peak only ST Shudehill GATE Oxford Road Station Monday to Friday: BRIDGE ST ST Exchange 6:30 – 9:10am People’s Square King Street Whitworth Street West HOME / First Street IRWELL ST History Royal Cross Street Gloucester Street Bridgewater Hall and 4 – 6:30pm Museum Barton Exchange Manchester Craft & Manchester Central DEANSGATE Arcade/ Arndale Design Centre HIGH ST Deansgate Station Castlefield SPINNINGFIELDS St Ann’s Market Street Royal Exchange Theatre Deansgate Locks John Square Market NEW -

Historicmanchester

HISTORIC MANCHESTER WALKING GUIDE 1 HISTORY IS EVERYWHERE 1 This guide has been produced Contents by the Heart of Manchester Business Improvement District (BID), on behalf of the city centre’s retailers, with the support of CityCo. Find out more at manchesterbid.com Editor Susie Stubbs, Modern Designers Design and illustration Modern Designers 4 Introduction Photography Felix Mooneeram 8 Walk: © Heart of Manchester King Street BID Company Ltd. 2017; to Chetham’s Design © Modern Designers 2017. All rights reserved. No part of this 34 Shops with a publication may be copied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted story to tell in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for purpose 40 Food and drink of review, and no part of this with a back story publication may be sold or hired, without the written permission of the publisher. 46 A little culture Although the authors have taken all reasonable care in preparing this book, we make no warranty about the accuracy or completeness of its content and, to the maximum extent permitted, disclaim all liability arising from its use. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. 2 3 Introduction Manchester is a city that wears its past with pride. Polished cars may purr up Deansgate and new-builds might impress passersby with all their glass and steel glory, but this is a city that has seen it all before. -

Enjoy Free Travel Around Manchester City Centre on a Free

Every 10 minutes Enjoy free travel around (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) Monday to Friday: 7am – 10pm GREEN free QUARTER bus Manchester city centre Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm Every 12 minutes Manchester Manchester Victoria on a free bus Sunday and public holidays: Arena 9:30am – 6pm Chetham’s VICTORIA STATION School of Music APPROACH Victoria Every 10 minutes GREENGATE Piccadilly Station Piccadilly Station (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) CHAPEL ST TODD NOMA Monday to Friday: 6:30am – 10pm ST VICTORIA MEDIEVAL BRIDGE ST National Whitworth Street Sackville Street Campus Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm QUARTER Chorlton Street The Gay Village ootball Piccadilly Piccadilly Gardens River Irwell Cathedral Chatham Street Manchester Visitor Every 12 minutes useum BAILEYNEW ST Information Centre Whitworth Street Palace Theatre Sunday and public holidays: orn The India House 9:30am – 6pm Exchange Charlotte Street Manchester Art Gallery CHAPEL ST Salford WITHY GROVEPrintworks Chinatown Portico Library Central MARY’S MARKET Whitworth Street West MMU All Saints Campus Peak only ST Shudehill GATE Oxford Road Station Monday to Friday: BRIDGE ST ST Exchange 6:30 – 9:10am People’s Suare King Street Whitworth Street West HOME / First Street IRWELL ST History Royal Cross Street Gloucester Street Bridgewater Hall and 4 – 6:30pm useum Barton Exchange Manchester Craft & Manchester Central DEANSGATE Arcade/ Arndale Design Centre HIGH ST Deansgate Station Castlefield SPINNINGFIELDS St Ann’s Market Street Royal Exchange Theatre Deansgate Locks John Suare Market NEW Centre -

Manchester Science Festival

Manchester Thursday 18 October – Science Sunday 28 October Festival Produced by Welcome to Manchester Science Festival It’s a huge pleasure to introduce this Create, play and experiment with science year’s programme. at this year's Manchester Science Festival. This Festival started life twelve years Experience what it's like to step inside a ago as a small, grassroots event and black hole with Distortions in Spacetime, has grown steadily to become the a brand new immersive artwork by largest, most playful and most popular cutting-edge audiovisual pioneers Science Festival in the country. Marshmallow Laser Feast. Play among gravitational waves and encounter one Here at the Science and Industry of the biggest mysteries of the universe. Museum we’re immensely proud to produce the Festival each year as it is Electricity: The spark of life is our an incredible opportunity to work with headline exhibition for 2018. Explore wonderful partners and venues across with us this vital but invisible force Greater Manchester. All of our partners from its discovery in nature to our continue to surprise us with new ideas high tech dependence on it today. for ways to get more people excited Award-winning data design studio about the science that shapes our lives. Tekja has created a new “electric” installation that captures the sheer On behalf of the wider Festival scale of electricity used in the North community, I would like to extend West. This beautiful and thought- a particularly warm welcome to all our provoking experience will encourage new partners this year, from community you to imagine the new ways electricity interest company Reform Radio to might be made and used in the future. -

RIBA Conservation Register

Conservation 17 If you are looking to commission work on a heritage building, you will need an architect with specific skills and experience. Our register of specialists encompasses all aspects of historic building conservation, repair and maintenance. For more information visit: www.architecture.com/findanarchitect/ FindaConservationArchitect by Tier RIBA Conservation Register 287 RICHARD BIGGINS DENIS COGAN ROISIN DONNELLY Frederick Gibberd Partnership, 117-121 Curtain Road, Kelly and Cogan Architects, 28 Westminster Road, Stoneygate, Consarc Design Group Ltd, The Gas Office, 4 Cromac Quay, Specialist Conservation Architect London EC2A 3AD Leicester LE2 2EG /81 North King Street, Smithfield, Dublin 7, Belfast BT7 2JD T 0207 739 3400 Republic of Ireland T 028 9082 8400 GIBSON (SCA) [email protected] T +353 (0) 1 872 1295/ 07557 981826 [email protected] ALEXANDER www.gibberd.com deniscogan@kelly andcogan.ie www.consarc-design.co.uk SCA CHRISTOPHER BLACKBURN JULIET COLMAN SIMON DOUCH SCA Has authoritative knowledge of Burnside House, Shaftoe Crescent, Hexham, JCCH, Kirby House, Pury End, Towcester, Northants NN12 7NX HOK International, The Qube, 90 Whitfield Street, London W1T 4EZ conservation practice and extensive Northumberland NE46 3DS T 01327 811453 T 020 7898 5119 T 01434 600454 / 07543 272451 [email protected] [email protected] experience of working with historic [email protected] www.jcch-architect.co.uk www.hok.com www.christopherblackburn-architect.co.uk buildings. CHRISTOPHER -

Pride Shuttle Services and Bus Departure Points 2019

T EE STR N TIO Y RA A PO G W OR Temporary bus arrangements T C D ITY U RIN A C T 6 IE 6 5 S Manchester Pride Parade, T T R S E E N Sorting Office T IO T Saturday 24 August 11am – 6pm 4 Visit www.tfgm.com A Manchester A 66 5 R Co-op A Arena 6 O Building P Parade starts at 12 noon from Liverpool Road for further details A Victoria R N O C G Station E D L A O ANGEL S R 2 T 4 SQUARE R Victoria 0 E LE T 6 E H Fire Station T A O Shuttlebus 1 Piccadilly (Stop S) to the Aquatics Centre/Oxford Road A D M M H V I C P I L S C L O O T ER R N O Shuttlebus 2 Piccadilly Gardens (Stop P) to Shudehill Interchange NK R A IA B E S S T T A S E N T T U A G T H L R N T L E Shuttlebus 3 Piccadilly (Stop S) to Deansgate station I I E A O New M E E N L T R Century A T S P S House T P R Shudehill Interchange R H A E O N CIS E A B O A V T L G E D C R Tower A N (StandD B) H O C L L I S Y K T N E R A F E G E V T R T Scale 1 : 3700 W E A AT I LG O A Chetham's IL R 2 T N R M 6 O S G School BA A L 36, 37, 38 D L O D O of Music H 0 100 200 yards N A G N N T S O E N V S T O S ER T E O I T L Shuttlebus 2 D R R L RE ST S R T T ET IL E A 0 100 200 metres O S W E O A T A H R D S E A T R CT National D N T U O U D S Football Shudehill H Crowne Plaza IA P Cinema S M V Hotel Museum R Interchange HA Y A CATHEDRAL O I D T L I R GARDENS C O N I O R T Travelshop Holiday Inn T C Manchester I The Printworks Express S V V Cathedral T IC R T E PEL O E Lever Street HA R Corn Exchange T C I W Shudehill A I (Stop EM) T B H Centre for Chinese R Y Contemporary Art T S H T G L O Manchester -

ENG 1859 Dobbinb J

DIREaTC)RY.] THADES DlRECTORY. ENG 1859 DobbinB J. T. 4 and 6 Grove st. Ardwick green Barlow & Chidlaw, Limited (machine cut Curtis, Sons & Co. (John Hetherington & Sons, Griffiths Thomas & Co. Lees Street gears), Croft st. P . Limited,engineers,Pollardst.),Phcenix works, Mills, Ancoats *Barlow H. ·B. & Gillett, Chartered Chapel Bt. Ancoats Jones Willlam C. Limited, Appleto patent agents, <1 Mansfield cham- "Dagnall Bros. (practical lanndry' st. Collyhurstrd bers, 17 St. Ann's square-T 11 engineers), Leaf st. Greenheys TN 15x "MONOPOLY, Manchester;" TN <1,018 Rm;ho;rne Kelsall H. M. & Co. 23 Fountain st Central . Dalziel James, (;3 Olifton st. 0 T Livingston JohnH. S. Minerva Works (dealers), Beacon (The) Engineering Co. Limited, 17 Davidson & Co. Limited, 37 Corporation st Hendham vale, Queen's rd St. Ann's SQ Davies C. & Co. 43 City rd. H Pettitt E.' S. & CO, (under royal Bell Bros. 41 Corporation at Dean & )Iatthews, 7·5 Trafford I'd. S letters patent, an improved Beresforrl (The) Co. Ltd. Dickinson st. S De Bergue & Co. Ltd. Strangeways lron Works. method for making engine waste, Berkel & Parnall, Marsdp.n court, Fennp.l st Mary st. Strangeways thus rendering it softer..:_cleaner & Beyer, m Peacock & Co. Limited (locomotive Devoge & Co. Sycamore st. Oldham ra longer). King Street mill. King & tramway engine), Gorton Foundry, Gm·ton Dixon W. F. & Co. 60 Percival st. C on M street, Salford, and at Ashton and la. Gorton Donat &; Co. 21 Spring gardens Oldham-'l' N 1,501 Central; TA Birch Edward & Co. 47 Rochdale rd roDonovan & Co. Limited Broughton "HBLOS, Manchester" Birch G. -

Download Brochure

PARK VIEW PARK PARK VIEW PARK VIEW PARK PARK VIEW Landmark Living 05 for Manchester Set in between the greenery of the City River Park and the hustle and bustle of the city centre, this landmark development is home to 634 new apartments and townhouses in Manchester’s emerging Red Bank neighbourhood. The one, two and three bed homes are spread across a family of three towers and two podium buildings. The facade of the building has striking colours which reflects the view which can be seen from the floor-to-ceiling, ‘picture-frame’ windows that each apartment enjoys, making the character of the local area an integral part of every home. Victoria Riverside marks a new chapter for this fast-growing city, putting you in prime position to embrace Manchester’s shopping, art and culture, all while enjoying the trees, parks and open spaces of the City River Park which has received £51.6 million of central government investment. 07 The North of England's biggest urban renewal project Over 15,000 new homes Over £1 billion total investment £51.6 million central government investment into a new City River Park New schools, healthcare facilities and transport links 155 hectares A planned new community of over 40,000 people Victoria Riverside marks the first phase of Victoria North (previously Manchester's Northern Gateway), the biggest renewal project Manchester’s ever seen. Jointly developed and funded by FEC and Manchester City Council, Victoria North is set to create 15,000 new homes across 155 hectares and seven neighbourhoods over the next 20 years, helping with the shortfall in housing in Manchester. -

7 Manchester Entdecken

7 Manchester entdecken 8 Manchester für Citybummler 9 Manchester an einem langen Wochenende 10 Das gibt es nur in Manchester 12 Stadtspaziergang 14 Mittendrin: das City Centre 14 O Town Hall ★ ★ * [D3] 15 O Albert Square ★ ★ [D3] 16 O Free Trade Hall ★ [C4] 17 O The Midland ★ [D4] 18 O Central Library ★ * [D4] 19 O Manchester Art Gallery ★ ★ ★ [D4] 20 O The Portico Library and Gallery ★ [D3] 20 O St Mary's Church ★ [C3] 20 O St Ann's Square und St Ann's Church ★ ★ [C3] 22 € > The Royal Exchange ★ ★ [D2] 22 Die Manchester-Bombe 23 <D Barton Arcade ★ [C2] 23 O National Football Museum ★ ★ [D2] 24 <E> Manchester Cathedral ★ ★ [D2] 25 <D Chetham's Library and School of Music ★ ★ ★ [D1] 26 Friedrich Engels in Manchester 27 Deansgate, Spinningfields, Castlefield 27 O John Rylands Library ★ ★ ★ [C3] 28 O People's History Museum ★ ★ [B3] 29 Beetham Tower ★ [C5] 29 CD Museum of Science and Industry ★ ★ ★ [B4] 31 „ What Manchester does today ..." - d ie Stadt der Innovation 33 <E> Castlefield ★ ★ ★ [B5] 34 Germancs - die Deutschen in Manchester 37 HOME ★ ★ [C5] 37 O Bridgewater Hall ★ [C5] 38 Der Kulturkorridor: rund um die Oxford Road 38 O The International Anthony Burgess Foundation ★ [D5] 38 O Manchester Museum ★ ★ [F7] 39 Spuk im Museum - der merkwürdige Tanz des Neb-Senu 39 O Holy Name Church ★ ★ [di] 40 O The Whitworth ★ ★ ★ [dj] 41 O Curry Mile ★ [dj] 41 O Elizabeth Gaskeil House ★ ★ [di] 42 O Victoria Baths ★ [ej] 43 Ausgehviertel: Chinatown, Gay Village, Northern Quarter 43 O Chinatown ★ [E4] 43 O Canal Street ★ ★ [E4] 44 O Piccadilly