An Australian Genre?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICHAEL YEZERSKI Composer FILM CREDITS

MICHAEL YEZERSKI Composer Michael Yezerski’s musical works are highly evocative, original and diverse. From the symphonic grittiness of THE TAX COLLECTOR to the quiet drama of BLINDSPOTTING; from the avant- garde horror drones of THE DEVIL’S CANDY to the heartfelt FEEL THE BEAT and THE BLACK BALLOON; Michael brings a signature musical intensity to every project he takes on. Hailing originally from Australia, and with a background in both contemporary concert music and electronic music production, Michael blends styles and influences in a way that pushes the boundaries of what dramatic film music can be. Rich in technique and sitting comfortably at the border with avant-garde music design, Michael’s work is nevertheless fundamentally human and melodic at its core. Born in Sydney, Michael is a multiple award-winning composer who creates music that is shaped from the perspective of an outsider – constantly fluid, ever changing, unbound by system – curious and always evolving. Recent projects include the hit international series MR INBETWEEN, Keith Thomas’ wondrously terrifying THE VIGIL and the Stephen Dorff starrer DEPUTY for FOX / Cedar Park. Earlier career highlights include HBO’s ONLY THE DEAD SEE THE END OF WAR, his first feature film THE BLACK BALLOON (winner of 8 AFI/AACTA Awards including Best Picture), PJ Hogan’s MENTAL, WOLF CREEK SERIES 2, CATCHING MILAT, PETER ALLEN, the Academy Award winning animated short, THE LOST THING and his collaboration with Richard Tognetti and the Australian Chamber Orchestra, THE RED TREE. Michael -

Year 7 / 2021 Please Note

Required Campion St Caths Office Book Title Edition RRP Selling Price Quantity Use Only Year 7 / 2021 please note Chinese Easy Steps to Chinese 1: Textbook & CD [Yamin Ma et al] required years 7 and 8 69.95 47 English Oxford Australian Pocket Dictionary (8E) (H/B) [Gwynn (Ed)] retain years 7-10 and VCE units 1-4 8E 29.95 20 English Hitlers Daughter (Novel) [French) CLEAN copy 16.99 11 English Wonder (P/B) [RJ Palacio] CLEAN copy 19.99 13 French Pearson Quoi de Neuf? 1SB/EB 2E (Comley et al) 2E 33.95 23 Geography/History Jacaranda AC 7 History Alive Print/LearnON 2E [Darlington] 2E 69.95 47 Geography/History Jacaranda AC 7 Geography Alive Print/LearnON/Atlas 2E [Mraz] Retain for years 7 & 8 2E 114.95 77 Japanese Hai 1 Textbook/Workbook [Burnham] CLEAN set only 52.95 35 set must be complete Japanese Hiragana in 48 Minutes Student Card Set [Quackenbush] required years 7 and 8 25.95 17 RRP reduced to 2/3 to reflect need to Mathematics Cambridge VIC Essential Maths 7 (Print & Digital) 2E (Greenwood et.al.) purchase reactivation code 2E (2020) 49 33 Science Cambridge VIC Science Year 7 (Print&Digital) [Shaw et.al.] 69.95 47 NOTE: St Cath's Science Resource Fee MUST be purchased through Campion as per book list TOTAL BOOKS CONSIGNED TO SALE THIS PAGE Required Campion St Caths Office Book Title Edition RRP Selling Price Quantity Use Only Year 8 /2021 please note Chinese Easy Steps to Chinese 2: Textbook & CD [Yamin Ma et al] required years 7 and 8 69.95 47 Chinese Easy Steps to Chinese 1: Textbook & CD [Yamin Ma et al] retain from Year 7 3E 69.95 -

Autism and Aspergers in Popular Australian Cinema Post-2000 | Ellis | Disability Studies Quarterly

Autism and Aspergers in Popular Australian Cinema Post-2000 | Ellis | Disability Studies Quarterly Autism & Aspergers In Popular Australian Cinema Post 2000 Reviewed By Katie Ellis, Murdoch University, E-Mail: [email protected] Australian Cinema is known for its tendency to feature bizarre and extraordinary characters that exist on the margins of mainstream society (O'Regan 1996, 261). While several theorists have noted the prevalence of disability within this national cinema (Ellis 2008; Duncan, Goggin & Newell 2005; Ferrier 2001), an investigation of characters that have autism is largely absent. Although characters may have displayed autistic tendencies or perpetuated misinformed media representations of this condition, it was unusual for Australian films to outright label a character as having autism until recent years. Somersault, The Black Balloon, and Mary & Max are three recent Australian films that explicitly introduce characters with autism or Asperger syndrome. Of the three, the last two depict autism with sensitivity, neither exploiting it for the purposes of the main character's development nor turning it into a spectacle of compensatory super ability. The Black Balloon, in particular, demonstrates the importance of the intentions of the filmmaker in including disability among notions of a diverse Australian community. Somersault. Red Carpet Productions. Directed By Cate Shortland 2004 Australia Using minor characters with disabilities to provide the audience with more insight into the main characters is a common narrative tool in Australian cinema (Ellis 2008, 57). Film is a visual medium that adopts visual methods of storytelling, and impairment has become a part of film language, as another variable of meaning within the shot. -

JANE GRIFFIN FREELANCE Line Producer / Production Manager [email protected] +61 417 213 967 Top Technicians Mgmt 02 9958 1611

JANE GRIFFIN FREELANCE Line Producer / Production Manager [email protected] +61 417 213 967 Top Technicians Mgmt 02 9958 1611 Below are highlights of projects I have worked on over the years. I believe it reflects my skills and breadth of experience . Please feel free to contact me if you require further specifics or clarification regarding my Resume. TVC: Production Management – some recent contracts Amarok Goodoil Films Precision driving and VFX on NSW largest Sheep Station Jim Beam Goodoil Films Cast and extras x 200 in around Sydney City streets over 3 days SI Amarni Beach House Films Cate Blanchett campaigns NSW Roads and Safety Paper Dragon Motor Bike Safety Campaign – large stunts and pyrotechnics Carnival Cruise Robbers Dog Filming on board the ship with a film crew of 20 between Syd and Sth Pacific DRAMA CREDITS : Production Line Producer Queer Eye YASS QUEEN Australian Promo for US TV Reality Line Producer Dead Beat Dads MTV Project 1 x ½ TV Pilot - Advisor Kim Vecera Scheduling PM The Shire Shine TV Australia Australian PM HG TV International Residents HIGH NOON TV USA: 2 x ½ hr episodes EP: Graham Clarke, Producer: Laurie Bain Prod Mgr One More Day NIDA/AFTRS 50YR Anniversary Feature Film Production Producers: Sandra Levy, Daphne Paris 4 x 1/2hr films Drama Producer Unfolding Florence Docu-Drama Dir: Gillian Armstrong / Prod: Sue Clotheir 2ND UNIT PM The Matrix Dir: Wachowski Bros / Prod: Joel Silver / Prod: Barry Osborne DRAMA CREDITS: Assistant Directing 2nd AD Ladies in Black Dir: Bruce Beresford/Prod: Sue Milliken 2nd AD Return to Devils Playground Matchbox Pictures: Producer Helen Bowden. -

Fax Transmission

LAWRENCE WOODWARD STUNT COORDINATOR 0417 405 540 [email protected] [email protected] 19 Jugiong Street, Pymble 2073 Australia Telephone:+61 2 9440 0070 Fax:+61 2 9440 3700 FEATURE FILMS, Stunt Coordinator Director: Fury Road Sequence Stunt Coord 2012 George Miller Beneath Hill 60 2009 Jeremy Sims Australia 2007 Baz Luhrmann The Black Balloon 2007 Elissa Down King Narasuen (Thailand) 2004 Chatri Yokul Cold Turkey 2002 Stephen McGregor Man Who Sued God 2001 Mark Joffe Garage Days 2001 Alex Proyas IMAX - Equus The Story of the Horse 2001 Micheal Caulfield Lantana 2000 Ray Lawrence Moulin Rouge Additional Coord 2000 Baz Luhrmann He Died with a Felafel in His Hand 1999 Richard Lowenstien Looking for Alibrandi 1998 Kate Woods Holy Smoke 1998 Jane Campion Thunderwith 1998 Simon Wincer Never Tell Me Never 1998 David Elflick A Wreck A Tangle 1998 Scott Paterson Terra Nova 1996 - 1997 Paul Middleditch Radiance 1997 Rachel Perkins The Boys 1997 Rowan Woods In The Winter Dark 1997 James Bogle TELEVISION FEATURES Survivors – Canyon (US) 2006 Nick Copus Survivors - Opposite of Lucky (UK) 2005 Nick Copus Salem’s Lot (US) 2003 Mikael Salomon South Pacific (US) 2000 Richard Pearce TELEVISION SERIES Ice (UK, shoot NZ) + 2nd UNIT DIRECTOR 2009 Nick Copus The Pacific (US) 2007 David Nutter Water Rats 2001 Amazon 1999 Water Rats 1999 Lost World 1999 Sabrina – Teenage Witch 1999 All Saints 1998 - 2001 Farscape 1998 - 1999 Wildside 1997 Home and Away 1997 19 Jugiong Street, Pymble 2073 Australia Telephone:+61 2 9440 0070 Fax:+61 2 9440 3700 -

All in the Family: Three Australian Female Directors Brian Mcfarlane

ALL IN THE FAMILY: THREE AUSTRALIAN FEMALE DIRECTORS BRIAN MCFARLANE y any standards, apart perhaps from box-office takings, 2009 was a banner year for Australian films. There were Balibo and Samson and Delilah, Disgrace and Last Ride, but what is really impressive is that three of the most memorable entries in this memorable year were directed by women, in an industry where Bdirection has long been dominated by men. I don’t want to make any special, essentialist point about what’s attracting female directors: male directors have been just as often drawn to the conflicts that rend families (think of such recent Australian films as Steve Jacobs’ Disgrace, Tony Ayres’ The Home Song Stories, Glendyn Ivin’s Last Ride, Dean Murphy’s Charlie & Boots). I just want to celebrate three very significant films by female directors. On the international scene, Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker has won and been nominated for numerous awards, and neither in this nor her earlier films has the family been the site of her chief interest. Perhaps film directing is no longer a male preserve, and female directors are not to be confined by the parameters of what used to be patronisingly characterised as ‘the women’s picture’. With this sort of proviso understood, the three major films I want to highlight here—Sarah Watt’s My Year without Sex, Rachel Ward’s Beautiful Kate and Ana Kokkinos’s Blessed—indeed foreground family matters and do so with rigour and perception, but there the similarities end. 82 The three films are tonally distinct from each other. -

Terror Nullius (2018) and the Politics of Sample Filmmaking

REVENGE REMIX: TERROR NULLIUS (2018) AND THE POLITICS OF SAMPLE FILMMAKING by Caitlin Lynch A Thesis SubmittEd for the DEgreE of MastEr of Arts to the Film StudiEs ProgrammE at ViCtoria University of WEllington – TE HErenga Waka April 2020 Lynch 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my supervisors, Dr. Missy Molloy and Dr. Alfio LEotta for their generous guidancE, fEEdbaCk and encouragemEnt. Thank you also to Soda_JErk for their communiCation and support throughout my resEarch. Lynch 3 ABSTRACT TERROR NULLIUS (Soda_JErk, 2018) is an experimEntal samplE film that remixes Australian cinema, tElEvision and news mEdia into a “politiCal revenge fablE” (soda_jerk.co.au). WhilE TERROR NULLIUS is overtly politiCal in tone, understanding its speCifiC mEssages requires unpaCking its form, contEnt and cultural referencEs. This thesis investigatEs the multiplE layers of TERROR NULLIUS’ politiCs, thereby highlighting the politiCal stratEgiEs and capaCitiEs of samplE filmmaking. Employing a historiCal mEthodology, this resEarch contExtualisEs TERROR NULLIUS within a tradition of sampling and other subversive modes of filmmaking, including SoviEt cinema, Surrealism, avant-garde found-footage films, fan remix videos, and Australian archival art films. This comparative analysis highlights how Soda_JErk utilisE and advancE formal stratEgiEs of subversive appropriation, fair usE, dialECtiCal editing and digital compositing to intErrogatE the relationship betwEEn mEdia and culture. It also argues that TERROR NULLIUS Employs postmodern and postColonial approaChes -

Network Films: a Global Genre?

Network Films: a Global Genre? Vivien Claire Silvey December 2012 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. ii This thesis is solely my original work, except where due reference is given. iii Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful for all the time and effort my dear supervisor Cathie Summerhayes has invested throughout this project. Her constant support, encouragement, advice and wisdom have been absolutely indispensable. To that master of words, puns and keeping his hat on during the toughest times of semester, Roger Hillman, I extend profound gratitude. Roger‟s generosity with opportunities for co-publishing, lecturing and tutoring, and enthusiasm for all things Turkish German, musical and filmic has been invaluable. For all our conversations and film-loans, I warmly say to Gino Moliterno grazie mille! I am indebted to Gaik Cheng Khoo, Russell Smith and Fiona Jenkins, who have provided valuable information, lecturing and tutoring roles. I am also grateful for the APA scholarship and for all the helpful administration staff in the School of Cultural Inquiry. At the heart of this thesis lies the influence of my mother Elizabeth, who has taken me to see scores of “foreign” and “art” films over the years, and my father Jerry, with whom I have watched countless Hollywood movies. Thank you for instilling in me a fascination for all things “world cinema”, for your help, and for providing a caring home. To my gorgeous Dave, thank you for all your love, motivation, cooking and advice. I am enormously honoured to have you by my side. -

Annual Report 2011/2012

ANNUAL REPORT 2011/2012 AUSTRALIAN FILM, TELEVISION AND RADIO SCHOOL Building 130, The Entertainment Quarter, Moore Park NSW 2021 PO Box 2286, Strawberry Hills NSW 2012 Tel + 61 (0)2 9805 6611 Fax + 61 (0)2 9887 1030 www.aftrs.edu.au NATIONAL PHONE: 1300 131 461 AFTRS © Australian Film, Television Radio School 2012 Published by the Australian Film, Television and Radio School ISSN 0819-2316 The text in this Annual Report is released subject to a Creative Commons BY- NC- ND licence, except for the text of the independent auditor’s report. This means, in summary, that you may reproduce, transmit and otherwise use AFTRS’ text, so long as you do not do so for commercial purposes and do not change it. You must also attribute the text you use as extracted from the Australian Film, Television and Radio School’s Annual Report. For more details about this licence, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.en_GB. This licence is in addition to any fair dealing or other rights you may have under the Copyright Act 1968. You are not permitted to reproduce, transmit or otherwise use any still photographs included in this Annual Report, without first obtaining AFTRS’ written permission. The report is available at the AFTRS website http://www.aftrs.edu.au 1 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister It is with great pleasure that I present the Annual Report for the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS) for the financial year ended 30 June 2012. -

Annual Report 2014-2015

AUSTRALIAN FILM, TELEVISION AND RADIO SCHOOL Building 130, The Entertainment Quarter, Moore Park NSW 2021 PO Box 2286, Strawberry Hills NSW 2012 Tel: 1300 131 461 Tel: +61 (0)2 9805 6611 Fax: +61 (0)2 9887 1030 www.aftrs.edu.au © Australian Film, Television and Radio School 2015 Published by the Australian Film, Television and Radio School ISSN 0819-2316 The text in this Annual Report is released subject to a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND licence, except for the text of the independent auditor’s report. This means, in summary, that you may reproduce, transmit and otherwise use AFTRS’ text, so long as you do not do so for commercial purposes and do not change it. You must also attribute the text you use as extracted from the Australian Film, Television and Radio School’s Annual Report. For more details about this licence, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ deed.en_GB. This licence is in addition to any fair dealing or other rights you may have under the Copyright Act 1968. You are not permitted to reproduce, transmit or otherwise use any still photographs included in this Annual Report, without first obtaining AFTRS’ written permission. The report is available at the AFTRS website http://www.aftrs.edu.au Cover Image: Production still from AFTRS student film Foal 2014. Photo courtesy of Vanessa Gazy. LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 28 August 2015 Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister It is with great pleasure that I present the Annual Report for the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS) for the financial year ended 30 June 2015. -

Movie Museum MAY 2010 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum MAY 2010 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY IT'S COMPLICATED Hawaii Premiere! PIRATE RADIO Mother's Day Hawaii Premiere! (2009) THE FIRST DAY OF THE aka The Boat that Rocked Hawaii Premiere! DEFAMATION in widescreen REST OF YOUR LIFE (2009-UK/Germany/US/ THE FIRST DAY OF THE aka Hashmatsa (2008-France) France) REST OF YOUR LIFE (2009-Israel/Denmark/US/ with Meryl Streep, Steve in French with English in widescreen (2008-France) Austria) Martin, Alec Baldwin, John subtitles & in widescreen with Philip Seymour in French with English in Hebrew/English with English Krasinski, Lake Bell, with Jacques Gamblin, Zabou Hoffman, Bill Nighy, Tom subtitles & in widescreen subtitles & in widescreen Mary Kay Place. Breitman, Déborah François. Sturridge, Nick Frost. with Jacques Gamblin, Zabou A documentary exploring anti- Breitman, Déborah François. Semitism's significance today. Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Nancy Meyers. Rémi Bezançon. Richard Curtis. Rémi Bezançon. Yoav Shamir. 12:15, 2:30, 4:45, 7:00 & 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:15, 2:30, 4:45, 7:00 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 9:15pm 6 & 8:30pm 7 & 9:15pm 8 & 8:30pm 9 & 8:30pm 10 Hawaii Premiere! Hawaii Premiere! Armed Forces Day Hawaii Premiere! Hawaii Premieres! TETRO DEFAMATION Hawaii Premieres! TETRO ECHOES OF HOME (2009-US/Italy/Spain/ aka Hashmatsa THE WINTER WAR (2009-US/Italy/Spain/ (2007-Switzerland/Germany) Argentina) (2009-Israel/Denmark/US/ (1989-Finland) Argentina) A delightful documentary on in widescreen Austria) in Finnish with English in widescreen yodeling in the 21st century. -

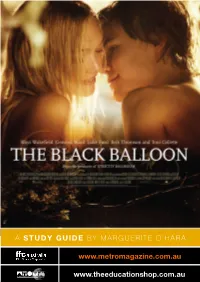

Blackballoonstudy Guide

A STUDY GUIDE BY MARGUERITE O’HARA www.metromagazine.com.au www.theeducationshop.com.au THE BLACK BALLOON Introduction wooden spoon and wailing on the front lawn. Charlie doesn’t The Black Balloon (Elissa Down, speak. He’s autistic and has 2007) is an Australian film ADD. He’s also unpredictable, about a family dealing with the sometimes unmanageable, and day-to-day challenges of living often disgusting. Thomas hates with an autistic son. Charlie his brother but wishes he didn’t. is seventeen and presents all kinds of embarrassing The Mollisons are an army situations for Thomas, his 15 family; but it’s not what you’d (going on 16)-year-old brother. call a regimented life, or even The film deals with a number a regular household. Thomas’s It’s hard to of issues about family life and cricket-obsessed father, Simon, the difficulties, challenges and talks to his teddy. Simon and fit in, when rewards faced by families in Maggie are openly intimate, and which one of the members has now Maggie is going to have you’re the a disability. another baby. The warmth, humour, love and One morning, the semi-naked generosity of the Mollison family Charlie escapes the house odd one out. makes for a very engaging film and leads Thomas on a chase that is neither sentimental nor across the neighbourhood. grim in its depiction of growing Charlie bursts into a stranger’s up with a family member with house to use the toilet; and autism. It is an inspiring story Thomas finds himself face to about the power of love, family face with Jackie Masters, his and friendship.