CTEER Brexit Update 2017.08.09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland

BRIEFING PAPER Number 4258, 19 June 2015 By Cheryl Pilbeam The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Historical background 3. The Wilson doctrine 4. Prison surveillance 5. Damian Green 6. The NSA files and metadata 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 4258, 19 June 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Historical background 4 3. The Wilson doctrine 5 3.1 Criticism of the Wilson doctrine 6 4. Prison surveillance 9 4.1 Alleged events at Woodhill prison 9 4.2 Recording of prisoner’s telephone calls – 2006-2012 10 5. Damian Green 12 6. The NSA files and metadata 13 6.1 Prism 13 6.2 Tempora and metadata 14 Legal challenges 14 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring 15 Cover page image copyright: Chamber-070 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped 3 The Wilson Doctrine Summary The convention that MPs’ communications should not be intercepted by police or security services is known as the ‘Wilson Doctrine’. It is named after the former Prime Minister Harold Wilson who established the rule in 1966. According to the Times on 18 November 1966, some MPs were concerned that the security services were tapping their telephones. In November 1966, in response to a number of parliamentary questions, Harold Wilson made a statement in the House of Commons saying that MPs phones would not be tapped. More recently, successive Interception of Communications Commissioners have recommended that the forty year convention which has banned the interception of MPs’ communications should be lifted, on the grounds that legislation governing interception has been introduced since 1966. -

Peter Hitchens on Whether the European Argues That Great Britain the Union Has Changed Britain Is a Nation in Decline Progressive Conscience

DAMIAN GREEN MP PETER HITCHENS on whether the European argues that Great Britain The Union has changed Britain is a nation in decline Progressive Conscience From Global Empire to the Global Race: modern Britishness john redwood mp | professor tim bale | daniel hannan mep | stephen crabb mp Contents 03 Editor’s introduction 18 Daniel Hannan: To define Contributors James Brenton Britain, look to its institutions PROF TIM BALE holds the Chair James Brenton politics in Politics at Queen Mary 20 Is Britain still Great? University of London 04 Director’s note JAMES BRENTON is the editor of Peter Hitchens and Ryan Shorthouse Ryan Shorthouse The Progressive Conscience 23 Painting a picture of Britain NICK CATER is Director of 05 Why I’m a Bright Blue MP the Menzies Research Centre Alan Davey George Freeman MP in Australia 24 What’s the problem with STEPHEN CRABB MP is Secretary 06 Replastering the cracks in the North of State for Wales promoting British values? Professor Tim Bale ROSS CYPHER-BURLEY was Michael Hand Spokesman to the British 07 Time for an English parliament Embassy in Tel Aviv 25 Multiple loyalties are easy John Redwood MP ALAN DAVEY is the departing Damian Green MP Arts Council Chief Executive 08 Britain after the referendum WILL EMKES is a writer 26 Influence in the Middle East Rupert Myers GEORGE FREEMAN MP is the Ross Cypher-Burley Minister for Life Sciences 09 Patriotism and Wales DR ROBERT FORD lectures at 27 Winning friends in India Stephen Crabb MP the University of Manchester Emran Mian DAMIAN GREEN MP is the 10 Unionism -

South East Coast

NHS South East Coast New MPs ‐ May 2010 Please note: much of the information in the following biographies has been taken from the websites of the MPs and their political parties. NHS BRIGHTON AND HOVE Mike Weatherley ‐ Hove (Cons) Caroline Lucas ‐ Brighton Pavillion (Green) Leader of the Green Party of England and Qualified as a Chartered Management Wales. Previously Green Party Member Accountant and Chartered Marketeer. of the European Parliament for the South From 1994 to 2000 was part owner of a East of England region. company called Cash Based in She was a member of the European Newhaven. From 2000 to 2005 was Parliament’s Environment, Public Health Financial Controller for Pete Waterman. and Food Safety Committee. Most recently Vice President for Finance and Administration (Europe) for the Has worked for a major UK development world’s largest non-theatrical film licensing agency providing research and policy company. analysis on trade, development and environment issues. Has held various Previously a Borough Councillor in positions in the Green Party since joining in 1986 and is an Crawley. acknowledged expert on climate change, international trade and Has run the London Marathon for the Round Table Children’s Wish peace issues. Foundation and most recently last year completed the London to Vice President of the RSPCA, the Stop the War Coalition, Campaign Brighton bike ride for the British Heart Foundation. Has also Against Climate Change, Railfuture and Environmental Protection completed a charity bike ride for the music therapy provider Nordoff UK. Member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament National Robbins. Council and a Director of the International Forum on Globalization. -

2001 GA Ann Report.A/W

Printed by Seacourt Press Limited on recycled paper made from 75% de-inked post consumer waste and a maximum of 25% mill broke. Seacourt have EMAS and ISO14001 accreditation, are members of the waterless printing association and their carbon emissions are offset. EMAS registration number UK-5-0000073. annual report 2000/01 our mission Green Alliance exists to promote sustainable development by ensuring that the environment is at the heart of decision-making We work with senior people in government, parliament, business and the environment movement to encourage new ideas, dialogue and constructive solutions. Green Alliance has three main aims: > to make the environment a central political issue > to integrate the environment effectively in public policy and decision-making > to stimulate new thinking and advance the environmental agenda into new areas The publication of this report has been supported by Severn Trent plc and the DEFRA Environmental Action Fund chair’s report Green Alliance’s increased strategic focus over the past two years is paying dividends. Our efforts to engage the Prime Minister and his officials on the environment succeeded, with Tony Blair’s speech to a Green Alliance/CBI audience in October 2000. This was by no means the end of a process, but opened a new dialogue between the Prime Minister and environment groups. Another success was the publication of our detailed, consensual work on the role of negotiated agreements between government and business. This charts a course through opposing views, laying down a model of best practice of which government, business and NGOs can feel ownership. Two Green Alliance pamphlets received considerable attention. -

1 Andrew Marr Show, Damian Green 18 Sept 2016

1 ANDREW MARR SHOW, DAMIAN GREEN 18TH SEPT 2016 ANDREW MARR SHOW 18TH SEPTEMBER 2016 DAMIAN GREEN AM: We’ve been talking perhaps rather loosely this morning about a post-liberal era. And one of the headline writers suggest that, compared with the economic liberalism and so forth of past Conservatives, Theresa May represents a break. Do you recognise that language at all? DG: No. I think – I mean clearly liberal capitalism and western values are under threat, they need fighting for, but they always do. I always think this idea we’ve reached the point of the end of history, that Fukuyama analysis at the end of the 80s was optimistic nonsense. You always have to keep fighting for your values. But Theresa May and her government will fight for those broadly small ‘L’ liberal, free market values as hard as any previous Conservative government. AM: So do you see any change of tonal direction in this new government at all? DG: Well, there’s clearly a large element of continuity because we’re all still Conservatives and we’re all modernising conservatives. I think the Conservative Party went through a big change under David Cameron that was necessary and desirable and that element will continue. Of course any new prime minister has their own individual policy priorities, and indeed their own way of doing business and Theresa will do it in a different way. AM: I was going to invite you to explain further since you knew Theresa May for a long, long time. What do you think is the essence of the Theresa May approach? What is new and fresh about it? 2 ANDREW MARR SHOW, DAMIAN GREEN 18TH SEPT 2016 DG: Well, the essence of it is a desire to serve. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 29 November 2018 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. It has been updated to reflect the changes in the Cabinet following the resignations in the aftermath of the government’s proposed Brexit deal. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets. This gives the government a working majority of 13. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. -

List of Ministers' Interests

LIST OF MINISTERS’ INTERESTS CABINET OFFICE DECEMBER 2017 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Prime Minister 5 Attorney General’s Office 6 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy 7 Cabinet Office 11 Department for Communities and Local Government 10 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 11 Ministry of Defence 13 Department for Education 14 Department of Exiting the European Union 16 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 17 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 19 Department of Health 21 Home Office 22 Department for International Development 23 Department for International Trade 24 Ministry of Justice 25 Northern Ireland Office 26 Office of the Advocate General for Scotland 27 Office of the Leader of the House of Commons 28 Office of the Leader of the House of Lords 29 Scotland Office 30 Department for Transport 31 HM Treasury 33 Wales Office 34 Department for Work and Pensions 35 Government Whips – Commons 36 Government Whips – Lords 40 2 INTRODUCTION Ministerial Code Under the terms of the Ministerial Code, Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or could reasonably be perceived to arise, between their Ministerial position and their private interests, financial or otherwise. On appointment to each new office, Ministers must provide their Permanent Secretary with a list, in writing, of all relevant interests known to them, which might be thought to give rise to a conflict. Individual declarations, and a note of any action taken in respect of individual interests, are then passed to the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics team and the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests to confirm they are content with the action taken or to provide further advice as appropriate. -

Government and Opposition Reshuffle

18 January 2018 Government and opposition reshuffle At the start of January, Theresa May undertook a ministerial reshuffle, stating that the reshuffle brings “fresh talent into government” and ensures it “looks more like the country it serves.” The changes saw the promotion of sixteen women and an additional three ministers with responsibilities for housing, health and Brexit. Jeremy Hunt remains in post, overseeing the newly renamed Department of Health and Social Care. Stephen Barclay and Caroline Dinenage have replaced Philip Dunne as ministers of state, following his resignation. Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, announced 13 appointments to his frontbench, including Paula Sherriff, who becomes shadow minister of state for social care and mental health. This briefing includes: 1. A summary of the changes to government ministers 2. Ministerial responsibilities in the department of health and social care 3. An overview of changes to the shadow ministerial team 4. Changes made last year to the Liberal Democrat frontbench team 1. Changes to government ministers The reshuffle follows a series of cabinet resignations, the most recent being that of the first secretary of state and minister for the cabinet office, Damien Green. Green, the prime minister’s effective deputy, was a key ally of Theresa May and chaired 8 cabinet committees and taskforces. He departed the government after an investigation found he had breached the ministerial code. The secretaries for the “great offices of state” of the Treasury, Home Office and Foreign Office remain in place, and there were only minor changes to the cabinet. David Lidington, formerly the justice secretary, replaced Damian Green as minister for the cabinet office but not as first secretary of state, although it is likely he will deputise for May at PMQs. -

The Brexit Effect How Government Has Changed Since the EU Referendum

The Brexit Effect How government has changed since the EU referendum Lewis Lloyd About this report Implementing the result of the 2016 EU referendum has proven an unprecedented test for the UK Government – one that it has yet to pass. Brexit has challenged the status quo, upending conventions and inviting us to rethink how government, and politics more broadly, work in the UK. On the day the UK was originally scheduled to leave the EU, this report assesses the impact on six areas that have been particularly subject to the “Brexit Effect”: ministers, the civil service, public bodies, money, devolution, and Parliament. Our Brexit work The Institute for Government has a major programme of work looking at the negotiations, the UK’s future relationship with the EU and how the UK is governed after Brexit. Keep up to date with our comment, explainers and reports, read our media coverage, and find out about our events at: www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/brexit March 2019 Contents List of figures and tables 2 List of abbreviations 4 Summary 5 Introduction 6 1. Ministers 7 2. Civil service 13 3. Public bodies 17 4. Money 21 5. Devolution 25 6. Parliament 31 References 39 List of figures and tables Figure 1 Changes in Brexit ‘War Cabinet’ membership over time 8 Figure 2 Timeline of resignations under Theresa May, outside of reshuffles 9 Figure 3 Ministers and senior civil servants in DExEU, June 2016 to present 9 Figure 4 Percentage change in staff numbers (FTE) for whole civil service, Defra and the Home Office, 2010 –18 13 Figure 5 Percentage -

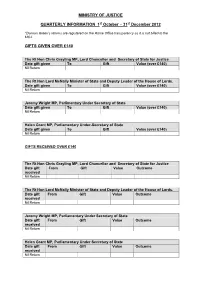

Moj Transparency Return Oct-Dec 2012

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE QUARTERLY INFORMATION 1st October – 31st December 2012 *Damian Green’s returns are registered on the Home Office transparency as it is not billed to the MOJ. GIFTS GIVEN OVER £140 The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return The Rt Hon Lord McNally Minister of State and Deputy Leader of the House of Lords. Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return Jeremy Wright MP, Parlimentary Under Secretary of State Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return Helen Grant MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Nil Return GIFTS RECEIVED OVER £140 The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil Return The Rt Hon Lord McNally Minister of State and Deputy Leader of the House of Lords. Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil Return Jeremy Wright MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil Return Helen Grant MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Nil Return OVERSEAS TRAVEL The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Date(s) Destination Purpose of ‘No 32 (The Number of Total cost of trip trip Royal) officials including Squadron’ accompanying travel and or ‘other Minister, where accommodati RAF’ or non-scheduled on of Minister ‘Charter’ or travel is used only ‘Eurostar’ Introductory 11.10.2 Meeting with £159 Paris 012 the French Justice Minister Introductory Meeting with German £721.15 24.10.2 Berlin Justice Minister 012 and German Members of Parliament 25.10.2 Justice and 012 - Home Affairs £817.73 Luxembourg 26.10.2 Committee 012 06.12.2 Justice and 012 - Home Affairs £503 Brussels 07.12.2 Committee 012 . -

Damian Green MP Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

Damian Green MP Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Dods People Profile Parliamentary and ministerial career Starting his political career in John Major’s policy unit in 1992, Green was elected to Parlia- ment in 1997 and quickly made it onto William Hague’s frontbench. He then held a number of positions under successive leaders, including shadow education, transport, and immigra- tion posts. During the Coalition he became Minister for Immigration, leaving the position in 2012 to be- come the Minister of State for Policing, Criminal Justice and Victims. Background Long on the pro-European left of the Party, he was chair of the Conservative Parliamentary Mainstream Group and backed Ken Clarke’s leadership campaign in 1997 and 2001. Nevertheless, his leadership loyalties came into question when he backed David Davis (now Secretary of State for Leaving the European Union) in 2005. As shadow immigration minister he received and made public a number of leaked Home Of- fice documents, leading to his arrest. He was accused by police of ‘grooming’ a sympathiser in the Home Office, although no charges came to light. During the coalition he promised to crack down on what he saw as migrants’ benefits cul- ture, introducing tough measures to try and reduce immigration. An example of this was where he defended the UKBA’s decision to withdraw sponsorship status from London Met- ropolitan University. He was then moved to cover policing for two years, which were comparatively uneventful. Despite his work on immigration he maintains a position on the left of the Party, having warned David Cameron not to listen to the “seductive chorus” of the right. -

Are We There Yet? a Collection on Race and Conservatism

are we there yet there we are are we there yet? | a collection onand race conservatism a collection a collection on race and conservatism Edited by Max Wind-Cowie Collection 31 Demos is a think-tank focused on power and politics. Our unique approach challenges the traditional, 'ivory tower' model of policymaking by giving a voice to people and communities. We work together with the groups and individuals who are the focus of our research, including them in citizens’ juries, deliberative workshops, focus groups and ethnographic research. Through our high quality and socially responsible research, Demos has established itself as the leading independent think-tank in British politics. In 2011, our work is focused on five programmes: Family and Society; Public Services and Welfare; Violence and Extremism; Public Interest and Political Economy. We also have two political research programmes: the Progressive Conservatism Project and Open Left, investigating the future of the centre-Right and centre-Left. Our work is driven by the goal of a society populated by free, capable, secure and powerful citizens. Find out more at www.demos.co.uk. First published in 2011 © Demos. Some rights reserved Magdalen House, 136 Tooley Street London, SE1 2TU, UK ISBN 978-1-906693-82-4 Copy edited by Susannah Wight Series design by modernactivity Typeset by modernactivity Set in Gotham Rounded and Baskerville 10 are we there yet? Edited by Max Wind-Cowie Open access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos wants to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright.