Ministers Reflect Richard Harrington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland

BRIEFING PAPER Number 4258, 19 June 2015 By Cheryl Pilbeam The Wilson Doctrine Pat Strickland Inside: 1. Introduction 2. Historical background 3. The Wilson doctrine 4. Prison surveillance 5. Damian Green 6. The NSA files and metadata 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 4258, 19 June 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Historical background 4 3. The Wilson doctrine 5 3.1 Criticism of the Wilson doctrine 6 4. Prison surveillance 9 4.1 Alleged events at Woodhill prison 9 4.2 Recording of prisoner’s telephone calls – 2006-2012 10 5. Damian Green 12 6. The NSA files and metadata 13 6.1 Prism 13 6.2 Tempora and metadata 14 Legal challenges 14 7. Labour MPs: police monitoring 15 Cover page image copyright: Chamber-070 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped 3 The Wilson Doctrine Summary The convention that MPs’ communications should not be intercepted by police or security services is known as the ‘Wilson Doctrine’. It is named after the former Prime Minister Harold Wilson who established the rule in 1966. According to the Times on 18 November 1966, some MPs were concerned that the security services were tapping their telephones. In November 1966, in response to a number of parliamentary questions, Harold Wilson made a statement in the House of Commons saying that MPs phones would not be tapped. More recently, successive Interception of Communications Commissioners have recommended that the forty year convention which has banned the interception of MPs’ communications should be lifted, on the grounds that legislation governing interception has been introduced since 1966. -

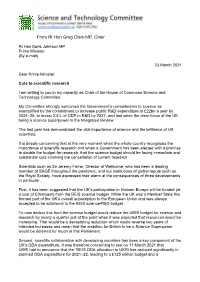

From Rt Hon Greg Clark MP, Chair

From Rt Hon Greg Clark MP, Chair Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP Prime Minister (By e-mail) 23 March 2021 Dear Prime Minister, Cuts to scientific research I am writing to you in my capacity as Chair of the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. My Committee strongly welcomes the Government’s commitments to science as exemplified by the commitment to increase public R&D expenditure to £22bn a year by 2024–25, to invest 2.4% of GDP in R&D by 2027, and last week the clear focus of the UK being a science superpower in the Integrated Review. The last year has demonstrated the vital importance of science and the brilliance of UK scientists. It is deeply concerning that at the very moment when the whole country recognises the importance of scientific research and when a Government has been elected with a promise to double the budget for research, that the science budget should be facing immediate and substantial cuts involving the cancellation of current research. Scientists such as Sir Jeremy Farrar, Director of Wellcome, who has been a leading member of SAGE throughout the pandemic, and our institutions of global repute such as the Royal Society, have expressed their alarm at the consequences of three developments in particular. First, it has been suggested that the UK’s participation in Horizon Europe will be funded (at a cost of £2bn/year) from the BEIS science budget. While the UK was a Member State this formed part of the UK’s overall subscription to the European Union and was always accepted to be additional to the BEIS science/R&D budget. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 11 January 2018 On 8-9 January 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May conducted a ministerial reshuffle. This guide has been updated to reflect the changes. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets, as well as Brexit and security matters, which are likely to dominate most of the current Parliament. This gives the government a working majority of 13. This is a briefing for BIA members on the new Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. Contents Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent -

Is the UK's Flagship Industrial Policy a Costly Failure?

Is the UK’s fagship industrial policy a costly failure? An Independent Reappraisal of the Objectives, Theory, Practice and Impact of the UK’s £7.3 Billion a Year R&D Tax Credits and £1.1 Billion a Year Patent Box Schemes David Connell Senior Research Associate, Centre for Business Research Cambridge Judge Business School Foreword by Greg Clark MP May 2021 Cambridge University Libraries Is the UK’s fagship industrial policy a costly failure? An Independent Reappraisal of the Objectives, Theory, Practice and Impact of the UK’s £7.3 Billion a Year R&D Tax Credits and £1.1 Billion a Year Patent Box Schemes David Connell Senior Research Associate, Centre for Business Research Cambridge Judge Business School Foreword by Greg Clark MP May 2021 Disclaimer: the views expressed are the author’s and not necessarily those of the Centre for Business Research CONTENTS Authors Biography vii About the Centre for Business Research viii Acknowledgements ix Foreword xi Executive Summary xiii Section 1: Introduction 1 Section 2: Some history; why UK industrial policy has become so dependent on tax breaks 3 Section 3: The UK R&D tax credit policy: theory and structure 7 Section 4: Economic impact of UK R&D tax credits 11 Section 5: Weaknesses in HMRC econometric evaluations 21 Section 6: A more realistic model of company behaviour 25 Section 7: The real policy challenge; how to grow and retain the UK’s science technology engineering and mathematics (STEM) based industries in an open economy 29 Section 8: Maximising the economic impact of R&D tax credits and other government policies on the STEM business economy 33 Section 9: Notes and references 39 vi BIOGRAPHIES Greg Clark MP David Connell Greg Clark is Member of Parliament for Tunbridge After a period with the UK’s National Economic Ofce, Wells and Chair of the Science and Technology David Connell joined Deloitte Haskins and Sells where Committee. -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Membership on the 28Th February 2019

Membership on the 28th February 2019 was: Parliamentarians Philip Hollobone MP House of Commons John Howell MP Nigel Adams MP The Rt Hon Sir Lindsay Hoyle MP Adam Afriyie MP Stephen Kerr MP Peter Aldous MP Peter Kyle MP The Rt Hon Kevin Barron MP Chris Leslie MP Margaret Beckett MP Ian Lavery MP Luciana Berger MP Andrea Leadsom MP Clive Betts MP Dr Phillip Lee MP Roberta Blackman-Woods MP Jeremy Lefroy MP Alan Brown MP Brandon Lewis MP Gregory Campbell MP Clive Lewis MP Ronnie Campbell MP Ian Liddell-Grainger MP Sir Christopher Chope MP Ian Lucas MP The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP Rachel Maclean MP Colin Clark MP Khalid Mahmood MP Dr Therese Coffey MP John McNally MP Stephen Crabb MP Mark Menzies MP Jon Cruddas MP David Morris MP Martyn Day MP Albert Owen MP David Drew MP Neil Parish MP James Duddridge MP Mark Pawsey MP David Duguid MP John Penrose MP Angela Eagle MP Chris Pincher MP Clive Efford MP Rebecca Pow MP Julie Elliott MP Christina Rees MP Paul Farrelly MP Antoinette Sandbach MP Caroline Flint MP Tommy Sheppard MP Vicky Ford MP Mark Spencer MP George Freeman MP Mark Tami MP Mark Garnier MP Jon Trickett MP Claire Gibson Anna Turley MP Robert Goodwill MP Derek Twigg MP Richard Graham MP Martin Vickers MP John Grogan MP Tom Watson MP Trudy Harrison MP Matt Western MP Sue Hayman MP Dr Alan Whitehead MP James Heappey MP Sammy Wilson MP Drew Hendry MP European Parliament Stephen Hepburn MP Linda McAvan MEP William Hobhouse Dr Charles Tannock MEP Wera Hobhouse MP Wera Hobhouse MP Parliamentarians Lord Stoddart of Swindon House of Lords The Lord Teverson Lord Berkeley Lord Truscott The Lord Best OBE DL Lord Turnbull Lord Boswell The Rt Hon. -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

Web of Power

Media Briefing MAIN HEADING PARAGRAPH STYLE IS main head Web of power SUB TITLE PARAGRAPH STYLE IS main sub head The UK government and the energy- DATE PARAGRAPH STYLE IS date of document finance complex fuelling climate change March 2013 Research by the World Development Movement has Government figures embroiled in the nexus of money and revealed that one third of ministers in the UK government power fuelling climate change include William Hague, are linked to the finance and energy companies driving George Osborne, Michael Gove, Oliver Letwin, Vince Cable climate change. and even David Cameron himself. This energy-finance complex at the heart of government If we are to move away from a high carbon economy, is allowing fossil fuel companies to push the planet to the government must break this nexus and regulate the the brink of climate catastrophe, risking millions of lives, finance sector’s investment in fossil fuel energy. especially in the world’s poorest countries. SUBHEAD PARAGRAPH STYLE IS head A Introduction The world is approaching the point of no return in the Energy-finance complex in figures climate crisis. Unless emissions are massively reduced now, BODY PARAGRAPH STYLE IS body text Value of fossil fuel shares on the London Stock vast areas of the world will see increased drought, whole Exchange: £900 billion1 – higher than the GDP of the countries will be submerged and falling crop yields could whole of sub-Saharan Africa.2 mean millions dying of hunger. But finance is continuing to flow to multinational fossil fuel companies that are Top five UK banks’ underwrote £170 billion in bonds ploughing billions into new oil, gas and coal energy. -

Resources/Contacts for Older People's Action Groups on Housing And

Resources/contacts for Older People’s Action Groups on housing and ageing for the next General Election It is not long before the next general election. Politicians, policy makers and others are developing their manifestos for the next election and beyond. The Older People’s Housing Champion’s network (http://housingactionblog.wordpress.com/) has been developing its own manifesto on housing and will be looking at how to influence the agenda locally and nationally in the months ahead. Its manifesto is at http://housingactionblog.wordpress.com/2014/08/07/our-manifesto-for-housing-safe-warm-decent-homes-for-older-people/ To help Older People’s Action Groups, Care & Repair England has produced this contact list of key people to influence in the run up to the next election. We have also included some ideas of the sort of questions you might like to ask politicians and policy makers when it comes to housing. While each party is still writing their manifesto in anticipation of the Party Conference season in the autumn, there are opportunities to contribute on-line at the party websites included. National Contacts – Politicians, Parties and Policy websites Name Constituency Email/Website Twitter www.conservatives.com/ Conservative Party @conservatives www.conservativepolicyforum.com/1 [email protected] Leader Rt Hon David Cameron MP Witney, Oxfordshire @David_Cameron www.davidcameron.com/ Secretary of State for Brentwood and Ongar, [email protected] Communities and Local Rt Hon Eric Pickles MP @EricPickles Essex www.ericpickles.com -

Peter Hitchens on Whether the European Argues That Great Britain the Union Has Changed Britain Is a Nation in Decline Progressive Conscience

DAMIAN GREEN MP PETER HITCHENS on whether the European argues that Great Britain The Union has changed Britain is a nation in decline Progressive Conscience From Global Empire to the Global Race: modern Britishness john redwood mp | professor tim bale | daniel hannan mep | stephen crabb mp Contents 03 Editor’s introduction 18 Daniel Hannan: To define Contributors James Brenton Britain, look to its institutions PROF TIM BALE holds the Chair James Brenton politics in Politics at Queen Mary 20 Is Britain still Great? University of London 04 Director’s note JAMES BRENTON is the editor of Peter Hitchens and Ryan Shorthouse Ryan Shorthouse The Progressive Conscience 23 Painting a picture of Britain NICK CATER is Director of 05 Why I’m a Bright Blue MP the Menzies Research Centre Alan Davey George Freeman MP in Australia 24 What’s the problem with STEPHEN CRABB MP is Secretary 06 Replastering the cracks in the North of State for Wales promoting British values? Professor Tim Bale ROSS CYPHER-BURLEY was Michael Hand Spokesman to the British 07 Time for an English parliament Embassy in Tel Aviv 25 Multiple loyalties are easy John Redwood MP ALAN DAVEY is the departing Damian Green MP Arts Council Chief Executive 08 Britain after the referendum WILL EMKES is a writer 26 Influence in the Middle East Rupert Myers GEORGE FREEMAN MP is the Ross Cypher-Burley Minister for Life Sciences 09 Patriotism and Wales DR ROBERT FORD lectures at 27 Winning friends in India Stephen Crabb MP the University of Manchester Emran Mian DAMIAN GREEN MP is the 10 Unionism