Muir Et Al. 2014. Vulnerability & Adaptation to Extreme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iona, Harris and Govan in Scotland Alastair Mcintosh

Offprint of chapter by Alastair Mclntosh - The 'Sacredness' of Natural Sites and Their Recovery: lona, Harris and Govan in Scotland, 2012 (full reference on final page). The full text of this book can be downloaded free from: IUCN www.iucn.org/dbtw-wpd/edocs/2012-006.pdf METSAHALLITUS ^WCPA ~~ WORLD COMMISSION ON PROTECTED AREAS The ‘sacredness’ of natural sites and their recovery: Iona, Harris and Govan in Scotland Alastair McIntosh Science and the sacred: with which science can, and even a necessary dichotomy? should, meaningfully engage? It is a pleasing irony that sacred natural In addressing these questions science sites (SNSs), once the preserve of reli- most hold fast to its own sacred value – gion, are now drawing increasing rec- integrity in the pursuit of truth. One ap- ognition from biological scientists (Ver- proach is to say that science and the schuuren et al., 2010). At a basic level sacred cannot connect because the for- this is utilitarian. SNSs frequently com- mer is based on reason while the latter prise rare remaining ecological ‘is- is irrational. But this argument invariably lands’ of biodiversity. But the very exist- overlooks the question of premises. ence of SNSs is also a challenge to sci- Those who level it make the presump- ence. It poses at least two questions. tion that the basis of reality is materialis- Does the reputed ‘sacredness’ of these tic alone. The religious, by contrast, ar- sites have any significance for science gue that the basis of reality, including beyond the mere utility by which they material reality, is fundamentally spiritu- happen to conserve ecosystems? And al. -

USEFUL CONTACTS a Directory of Local Support Organisations and Services

1 OUTER HEBRIDES DOMESTIC ABUSE FORUM ”… Sharing, Networking - Promoting Good Practice” USEFUL CONTACTS A Directory of Local Support Organisations and Services Outer Hebrides Domestic Abuse Forum – Useful Contacts Information collated by Maria MacDonald and Frank Creighton, CnES, September 2015 2 1. Housing & Housing Support 2. Drug & Alcohol Services 3. Health Services 4. Employment Support & Training 5. Mental Health Support & Counselling Services 6. Domestic Abuse Support Services 7. Financial and Welfare Services 8. Support for Families 9. National Services 10. Men’s Services Outer Hebrides Domestic Abuse Forum – Useful Contacts Information collated by Maria MacDonald and Frank Creighton, CnES, September 2015 3 1. Housing & Housing Support Co-Cheangal Innse Gall (CCIG) Furniture packs: Isle of Lewis: via Third Sector Hebrides – 01851 702632 Isle of Harris: via Harris Voluntary Service – 01859 502171 Isle of Uist: via UCVO – 01870 602117 Isle of Barra: via Voluntary Action Barra & Vatersay – 01871 810401 Crossreach – Lewis Street Project 6 Lewis Street, Stornoway, HS1 2JF 01851 706888 [email protected] www.crossreach.org.uk Supported Accommodation for 5 – 8 adults to prepare for greater independence. Hebridean Housing Partnership Creed Court, Gleann Seileach Business Park, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, HS1 2EP Winfield Way, Balivanich, Isle of Benbecula, HS7 5LH 0300 123 0773 [email protected] www.hebrideanhousing.co.uk Housing and prevention advice, housing assessments, temporary and permanent accommodation, housing support and resettlement, rent guarantee deposit scheme, referral to support agencies, tenancy set up support and advice on private sector leasing. Outer Hebrides Domestic Abuse Forum – Useful Contacts Information collated by Maria MacDonald and Frank Creighton, CnES, September 2015 4 Salvation Army Salvation Army Hall, 59 Bayhead, Stornoway, HS1 2DZ 01851703875 [email protected] www.salvationarmy.org.uk General advice and support. -

Towards a Sonic Methodology Cathy

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 11, No. 2, 2016, pp. 343-358 Mapping the Outer Hebrides in sound: towards a sonic methodology Cathy Lane University of the Arts London, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT: Scottish Gaelic is still widely spoken in the Outer Hebrides, remote islands off the West Coast of Scotland, and the islands have a rich and distinctive cultural identity, as well as a complex history of settlement and migrations. Almost every geographical feature on the islands has a name which reflects this history and culture. This paper discusses research which uses sound and listening to investigate the relationship of the islands’ inhabitants, young and old, to placenames and the resonant histories which are enshrined in them and reveals them, in their spoken form, as dynamic mnemonics for complex webs of memories. I speculate on why this ‘place-speech’ might have arisen from specific aspects of Hebridean history and culture and how sound can offer a new way of understanding the relationship between people and island toponymies. Keywords: Gaelic, island, landscape, memory, Outer Hebrides, place-speech, sound © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction I am a composer, sound artist and academic. In my creative practice I compose concert works and gallery installations. My current practice focuses around sound-based investigations of a place or theme and uses a mixture of field recording, interview, spoken text and existing oral history archive recordings as material. I am interested in the semantic and the abstract sonic qualities of all this material and I use it to construct “docu-music” (Lane, 2006). -

Sport & Activity Directory Uist 2019

Uist’s Sport & Activity Directory *DRAFT COPY* 2 Foreword 2 Welcome to the Sport & Activity Directory for Uist! This booklet was produced by NHS Western Isles and supported by the sports division of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and wider organisations. The purpose of creating this directory is to enable you to find sports and activities and other useful organisations in Uist which promote sport and leisure. We intend to continue to update the directory, so please let us know of any additions, mistakes or changes. To our knowledge the details listed are correct at the time of printing. The most up to date version will be found online at: www.promotionswi.scot.nhs.uk To be added to the directory or to update any details contact: : Alison MacDonald Senior Health Promotion Officer NHS Western Isles 42 Winfield Way, Balivanich Isle of Benbecula HS7 5LH Tel No: 01870 602588 Email: [email protected] . 2 2 CONTENTS 3 Tai Chi 7 Page Uist Riding Club 7 Foreword 2 Uist Volleyball Club 8 Western Isles Sports Organisations Walk Football (40+) 8 Uist & Barra Sports Council 4 W.I. Company 1 Highland Cadets 8 Uist & Barra Sports Hub 4 Yoga for Life 8 Zumba Uibhist 8 Western Isles Island Games Association 4 Other Contacts Uist & Barra Sports Council Members Ceolas Button and Bow Club 8 Askernish Golf Course 5 Cluich @ CKC 8 Benbecula Clay Pigeon Club 5 Coisir Ghaidhlig Uibhist 8 Benbecula Golf Club 5 Sgioba Drama Uibhist 8 Benbecula Runs 5 Traditional Spinning 8 Berneray Coastal Rowing 5 Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Classes 8 Berneray Community Association -

A Guided Wildlife Tour to St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides (Gemini Explorer)

A GUIDED WILDLIFE TOUR TO ST KILDA AND THE OUTER HEBRIDES (GEMINI EXPLORER) This wonderful Outer Hebridean cruise will, if the weather is kind, give us time to explore fabulous St Kilda; the remote Monach Isles; many dramatic islands of the Outer Hebrides; and the spectacular Small Isles. Our starting point is Oban, the gateway to the isles. Our sea adventure vessels will anchor in scenic, lonely islands, in tranquil bays and, throughout the trip, we see incredible wildlife - soaring sea and golden eagles, many species of sea birds, basking sharks, orca and minke whales, porpoises, dolphins and seals. Aboard St Hilda or Seahorse II you can do as little or as much as you want. Sit back and enjoy the trip as you travel through the Sounds; pass the islands and sea lochs; view the spectacular mountains and fast running tides that return. make extraordinary spiral patterns and glassy runs in the sea; marvel at the lofty headland lighthouses and castles; and, if you The sea cliffs (the highest in the UK) of the St Kilda islands rise want, become involved in working the wee cruise ships. dramatically out of the Atlantic and are the protected breeding grounds of many different sea bird species (gannets, fulmars, Our ultimate destination is Village Bay, Hirta, on the archipelago Leach's petrel, which are hunted at night by giant skuas, and of St Kilda - a UNESCO world heritage site. Hirta is the largest of puffins). These thousands of seabirds were once an important the four islands in the St Kilda group and was inhabited for source of food for the islanders. -

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE Iseag 185 Mìle • 10 Island a Iles • S • 1 S • 2 M 0 Ei Rrie 85 Lea 2 Fe 1 Nan N • • Area 6 Causeways • 6 Cabhsi WELCOME

A FREE CULTURAL GUIDE 185 Miles • 185 Mìl e • 1 0 I slan ds • 10 E ile an an WWW.HEBRIDEANWAY.CO.UK• 6 C au sew ays • 6 C abhsiarean • 2 Ferries • 2 Aiseag WELCOME A journey to the Outer Hebrides archipelago, will take you to some of the most beautiful scenery in the world. Stunning shell sand beaches fringed with machair, vast expanses of moorland, rugged hills, dramatic cliffs and surrounding seas all contain a rich biodiversity of flora, fauna and marine life. Together with a thriving Gaelic culture, this provides an inspiring island environment to live, study and work in, and a culturally rich place to explore as a visitor. The islands are privileged to be home to several award-winning contemporary Art Centres and Festivals, plus a creative trail of many smaller artist/maker run spaces. This publication aims to guide you to the galleries, shops and websites, where Art and Craft made in the Outer Hebrides can be enjoyed. En-route there are numerous sculptures, landmarks, historical and archaeological sites to visit. The guide documents some (but by no means all) of these contemplative places, which interact with the surrounding landscape, interpreting elements of island history and relationships with the natural environment. The Comhairle’s Heritage and Library Services are comprehensively detailed. Museum nan Eilean at Lews Castle in Stornoway, by special loan from the British Museum, is home to several of the Lewis Chessmen, one of the most significant archaeological finds in the UK. Throughout the islands a network of local historical societies, run by dedicated volunteers, hold a treasure trove of information, including photographs, oral histories, genealogies, croft histories and artefacts specific to their locality. -

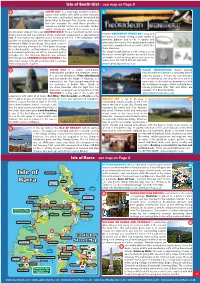

Isle of Barra - See Map on Page 8

Isle of South Uist - see map on Page 8 65 SOUTH UIST is a stunningly beautiful island of 68 crystal clear waters with white powder beaches to the west, and heather uplands dominated by Beinn Mhor to the east. The 20 miles of machair that runs alongside the sand dunes provides a marvellous habitat for the rare corncrake. Golden eagles, red grouse and red deer can be seen on the mountain slopes to the east. LOCHBOISDALE, once a major herring port, is the main settlement and ferry terminal on the island with a population of approximately Visit the HEBRIDEAN JEWELLERY shop and 300. A new marina has opened, and is located at the end of the breakwater with workshop at Iochdar, selling a wide variety of facilities for visiting yachts. Also newly opened Visitor jewellery, giftware and books of quality and Information Offi ce in the village. The island is one of good value for money. This quality hand crafted the last surviving strongholds of the Gaelic language jewellery is manufactured on South Uist in the in Scotland and the crofting industries of peat cutting Outer Hebrides. and seaweed gathering are still an important part of The shop in South Uist has a coffee shop close by everyday life. The Kildonan Museum has artefacts the beach, where light snacks are served. If you from this period. ASKERNISH GOLF COURSE is the are unable to visit our shop, please visit us on our oldest golf course in the Western Isles and is a unique online store. Tel: 01870 610288. HS8 5QX. -

HHP Newsletter.Indd

Customer Services 0300 123 0773 July 2014 hhomewardhebrideanom housinge partnershipwa newsletterrd How to get help with the Bedroom Tax Are you affected by the Bedroom Tax? Are you receiving Discretionary Housing Payments (DHP)? If you are affected by the Bedroom Council Leader Tax and are not currently Angus Campbell, receiving DHP then you Depute First are urged to make an Minister Nicola application. DHP is Sturgeon and HHP an additional Housing Chairman David Benefi t payment made Blaney with the by the Comhairle and phase 1 plans. it is a way to make up the shortfall between your weekly rent and Housing Benefi t award. Scottish Cabinet visit 16th April 2014 Speaking in a statement to Parliament on 7 May 2014, the Deputy First Minister Deputy First Minister Nicola Sturgeon houses and we are very proud of the quality Nicola Sturgeon asked households marked the start of work on the of our new homes both for rent and sale.” who have lost out on housing benefi t development at Melbost Farm that will Cllr Kenny Murray, the Chair of the through the ‘Bedroom Tax’ to access provide 32 affordable homes to rent and Comhairle’s Environment and Protective compensation through Discretionary buy in Stornoway. Services Committee said: “The Comhairle Housing Payments (DHP). The scheme is part of a wider plan for HHP is pleased to have been able to provide Ms Sturgeon said: to deliver 61 homes across the Western fi nancial support towards MacKenzie Isles by the summer of 2015, supported Crescent and to continue our close working “What the Scottish Government is by £4 million in funds from the Scottish relationship with HHP and the Scottish able to do is mitigate the impact of the Government. -

Balivanich Regeneration

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE 26 FEBRUARY 2020 POLICY AND RESOURCES COMMITTEE 4 MARCH 2020 BALIVANICH REGENERATION Report by Head of Economic Development and Planning PURPOSE OF REPORT To update the Comhairle on the Town Centre Fund and the regeneration of Balivanich as part of the Balivanich Strategic Vision. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, equalities or other constraints to the recommendations being implemented. The Comhairle was awarded a Town Centre Fund capital grant of £223,000 by the Scottish Government in March 2019. The Grant is to be committed by the end of March 2020. SUMMARY 2.1 The Comhairle endorsed the outcomes of the ‘Balivanich Strategic Vision’ in September 2018 and the phased approach to undertaking a range of short, medium and long term projects to support the regeneration of Balivanich. 2.2 In May 2019, the Comhairle agreed to prioritise the Balivanich Strategic Vision regeneration strategy for funding under the Town Centre Fund, providing the opportunity to accelerate a set of short term ‘quick win’ projects identified by the community in order to build confidence and commitment to the regeneration of Balivanich. The funding also provided the opportunity to finally implement aspects of the previous Building a Better Balivanich Community Plan and to focus resources on supporting aspects of the current North Uist and Benbecula Locality Plan. 2.2 The project proposals align with the Balivanich Strategic Vision and the North Uist and Benbecula Locality Action Plan. Presentations have been made to the North Uist and Benbecula Locality Group, Benbecula Community Council and Uist Economic Taskforce Working group. -

Barra, Eriskay & Vatersay the Uists & Benbecula

Map of the Uists, Benbecula and Barra EXPLORE THE OUTER HEBRIDES is part of a network of similar Guides, websites, social media and advice throughout Isle of Harris Scotland. Each area is managed by a separate organisation, all working together to provide consistent accurate tips and advice. 57 For more information go to: www.explorescotland.net | www.explore-western-isles.com Berneray BAILE To advertise in this guide contact: [email protected] 58 BORVE Tel: 01688 302075. To South Harris SOLLAS Hebridean Way Cycle Route 780 The Uists & 60 North 59 BAYHEAD Uist £ To Skye LOCHMADDYLOCH Benbecula Taigh Chearsabhagh BOWGLAS Museum & Arts Kirkibost Centre LOCHEPORT USEFUL TELEPHONE 56 CARINISH NUMBERS Golf Course 61 See Page 6 for more NORTH UIST £ detailed map Caledonian MacBrayne Hebridean Way BALIVANICH 61 62 63 64 Lochmaddy Cycle Route 780 01876 522509 NUNTON Benbecula Police Station Lochmaddy GRIMINISH 101 58 63 CREAGORRY BERNERAY SHOP LINICLATE AND BISTRO BENBECULA 61 EOCHAR 70 Police Station Balivanich MACLEAN’S 101 BAKERY & 68 LOCHCARNAN Uist & Barra BUTCHERS Hospital Balivanich SANDWICK 01870 603603 62 CHARLIE’S 69 HEBRIDEAN Loganair (flight enquiries) LOCHSKIPPORT 01870 602310 BISTRO STILLIGARY 64 THE STEPPING HOWMORE STONE South SOUTH UIST RESTAURANT Visitor Information 68 STONEYBRIDGE Uist Lochboisdale HEBRIDEAN 69 01878 700286 JEWELLERY SALAR Caledonian MacBrayne & CAFÉ SMOKEHOUSE Lochboisdale Hebridean Way 01878 700254 75 KILBRIDE CAFE, Cycle Route 780 70 ORASAY INN Police Station Lochboisdale HOSTEL AND Kildonan 101 CAMPSITE -

Annual Report 2020

2019 - 2020 Volunteer Centre Western Isles Annual Report Actively encouraging, supporting and promoting volunteering. Working at the heart of our communities since 1997 A certificate for Employer-Supported Volunteering was presented to the Isle of Harris Distillery for their commitment to community volunteering by allowing staff to take (paid) time off to help with local projects. This is the first award to an employer in Harris but we hope to see more gaining this recognition in future years. Shona Macleod and Harrison Wood, Isle of Harris Distillery, with the certificate for Employer-Supported Volunteering. We encourage our staff to get involved in local community volunteering, with paid days to participate in social, charitable and environmental activities. Isle of Harris Distillers 2 Actively encouraging, supporting and promoting volunteering Contents 4. About Us 4. Manager’s Report 5. Chair’s report 6. Our Trustees 7. Our Staff 8. What We Do i. Third Sector Interface Western Isles (TSIWI) ii. Building intelligence iii. Connect iv. Building capacity v. Voice 27. Finances www.volunteercentrewi.org 3 About us Volunteer Centre Western Isles is an • facilitate adult and youth volunteer independent local charity with offices and awards that recognise the staff in Lewis, Harris, Uist and Barra. achievements of volunteers We provide information, advice and support • facilitate volunteer awards for to individuals interested in volunteering, organisations who provide the best volunteer managers, voluntary groups, clubs experience for their -

An Archaeology of Isolation Emma Dwyer

Chap6-IPMAG2.qxd 26/11/2009 23:47 Page 131 6. Peripheral people and places: an archaeology of isolation Emma Dwyer Abstract This chapter explores the creation of a narrative of ‘isolation’ between the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries, focusing on the presentation of rural communities in Scotland, Wales and Ireland as passive and isolated from the cut and thrust of the metropolis. This narrative trope can be found in examples of travel writing and ethnography dating from the period 1750–1950, but is also apparent in more recent archaeological texts. Narratives of isolation can be fluid and can be manipulated. The ‘stories’ told in travel literature change over time, depending on the identities and motives of the groups involved; indeed, the value of travel accounts lies not so much in the ethnographic documentation of their subjects as in what they tell us about the motives of the people writing them. Introduction: Highlands and Islands The origins of models of isolated, primitive communities may be found in part in the literature that accompanied the European expansion of the eighteenth century, with the study of ethnographic and historical subjects soon extended to contemporary communities in the British Isles. For example, the natural historian Gilbert White, writing in 1789, advocated an exploration of Ireland similar to that undertaken by James Banks and James Cook in the Pacific between 1768 and 1780. White’s study was to involve the documentation of flora, fauna and ‘the manners of these wild natives, their superstitions, their prejudices, [and] their sordid way of life’ (White 1900, 178).