An Archaeology of Isolation Emma Dwyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Sonic Methodology Cathy

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 11, No. 2, 2016, pp. 343-358 Mapping the Outer Hebrides in sound: towards a sonic methodology Cathy Lane University of the Arts London, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT: Scottish Gaelic is still widely spoken in the Outer Hebrides, remote islands off the West Coast of Scotland, and the islands have a rich and distinctive cultural identity, as well as a complex history of settlement and migrations. Almost every geographical feature on the islands has a name which reflects this history and culture. This paper discusses research which uses sound and listening to investigate the relationship of the islands’ inhabitants, young and old, to placenames and the resonant histories which are enshrined in them and reveals them, in their spoken form, as dynamic mnemonics for complex webs of memories. I speculate on why this ‘place-speech’ might have arisen from specific aspects of Hebridean history and culture and how sound can offer a new way of understanding the relationship between people and island toponymies. Keywords: Gaelic, island, landscape, memory, Outer Hebrides, place-speech, sound © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction I am a composer, sound artist and academic. In my creative practice I compose concert works and gallery installations. My current practice focuses around sound-based investigations of a place or theme and uses a mixture of field recording, interview, spoken text and existing oral history archive recordings as material. I am interested in the semantic and the abstract sonic qualities of all this material and I use it to construct “docu-music” (Lane, 2006). -

Sport & Activity Directory Uist 2019

Uist’s Sport & Activity Directory *DRAFT COPY* 2 Foreword 2 Welcome to the Sport & Activity Directory for Uist! This booklet was produced by NHS Western Isles and supported by the sports division of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and wider organisations. The purpose of creating this directory is to enable you to find sports and activities and other useful organisations in Uist which promote sport and leisure. We intend to continue to update the directory, so please let us know of any additions, mistakes or changes. To our knowledge the details listed are correct at the time of printing. The most up to date version will be found online at: www.promotionswi.scot.nhs.uk To be added to the directory or to update any details contact: : Alison MacDonald Senior Health Promotion Officer NHS Western Isles 42 Winfield Way, Balivanich Isle of Benbecula HS7 5LH Tel No: 01870 602588 Email: [email protected] . 2 2 CONTENTS 3 Tai Chi 7 Page Uist Riding Club 7 Foreword 2 Uist Volleyball Club 8 Western Isles Sports Organisations Walk Football (40+) 8 Uist & Barra Sports Council 4 W.I. Company 1 Highland Cadets 8 Uist & Barra Sports Hub 4 Yoga for Life 8 Zumba Uibhist 8 Western Isles Island Games Association 4 Other Contacts Uist & Barra Sports Council Members Ceolas Button and Bow Club 8 Askernish Golf Course 5 Cluich @ CKC 8 Benbecula Clay Pigeon Club 5 Coisir Ghaidhlig Uibhist 8 Benbecula Golf Club 5 Sgioba Drama Uibhist 8 Benbecula Runs 5 Traditional Spinning 8 Berneray Coastal Rowing 5 Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Classes 8 Berneray Community Association -

Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles: Canna, Eigg, Muck, Rùm Report No: HAS051202 Client The Small Isles Community Council Date December 2005 Archaeology Development Plan for the Small Isles December 2005 Summary This report sets out general recommendations and specific proposals for the development of archaeology on and for the Small Isles of Canna, Eigg, Muck and Rùm. It reviews the islands’ history, archaeology and current management and visitor issues, and makes recommendations. Recommendations include ¾ Improved co-ordination and communication between the islands ¾ An organisational framework and a resident project officer ¾ Policies – research, establishing baseline information, assessment of significance, promotion and protection ¾ Audience development work ¾ Specific projects - a website; a guidebook; waymarked trails suitable for different interests and abilities; a combined museum and archive; and a pioneering GPS based interpretation system ¾ Enhanced use of Gaelic Initial proposals for implementation are included, and Access and Audience Development Plans are attached as appendices. The next stage will be to agree and implement follow-up projects Vision The vision for the archaeology of the Small Isles is of a valued resource providing sustainable and growing benefits to community cohesion, identity, education, and the economy, while avoiding unnecessary damage to the archaeological resource itself or other conservation interests. Acknowledgements The idea of a Development Plan for Archaeology arose from a meeting of the Isle of Eigg Historical Society in 2004. Its development was funded and supported by the Highland Council, Lochaber Enterprise, Historic Scotland, the National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage, and the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, and much help was also received from individual islanders and others. -

A Guided Wildlife Tour to St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides (Gemini Explorer)

A GUIDED WILDLIFE TOUR TO ST KILDA AND THE OUTER HEBRIDES (GEMINI EXPLORER) This wonderful Outer Hebridean cruise will, if the weather is kind, give us time to explore fabulous St Kilda; the remote Monach Isles; many dramatic islands of the Outer Hebrides; and the spectacular Small Isles. Our starting point is Oban, the gateway to the isles. Our sea adventure vessels will anchor in scenic, lonely islands, in tranquil bays and, throughout the trip, we see incredible wildlife - soaring sea and golden eagles, many species of sea birds, basking sharks, orca and minke whales, porpoises, dolphins and seals. Aboard St Hilda or Seahorse II you can do as little or as much as you want. Sit back and enjoy the trip as you travel through the Sounds; pass the islands and sea lochs; view the spectacular mountains and fast running tides that return. make extraordinary spiral patterns and glassy runs in the sea; marvel at the lofty headland lighthouses and castles; and, if you The sea cliffs (the highest in the UK) of the St Kilda islands rise want, become involved in working the wee cruise ships. dramatically out of the Atlantic and are the protected breeding grounds of many different sea bird species (gannets, fulmars, Our ultimate destination is Village Bay, Hirta, on the archipelago Leach's petrel, which are hunted at night by giant skuas, and of St Kilda - a UNESCO world heritage site. Hirta is the largest of puffins). These thousands of seabirds were once an important the four islands in the St Kilda group and was inhabited for source of food for the islanders. -

Sustainability Profile for North Uist and Berneray North Uist & Berneray

Sustainability Profile for North Uist and Berneray North Uist & Berneray CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Goal 1: Making the most of natural and cultural resources without damaging them 6 Objective 1: Protecting and enhancing natural resources and promoting their value 6 (Includes key topics – sea; fresh water; land; biodiversity; management) Objective 2: Protecting and enhancing cultural resources and promoting their value 9 (Includes key topics – language; arts; traditions; sites/ monuments: management, interpretation) Objective 3: Promoting sustainable and innovative use of natural resources 11 (Includes key topics – agriculture; fisheries and forestry; game; minerals; tourism; marketing) Objective 4: Promoting sustainable and innovative use of cultural resources 13 (Includes key topics – cultural tourism; facilities; projects; products; events; marketing) Goal 2: Retaining a viable and empowered community 14 Objective 5: Retaining a balanced and healthy population 14 (Includes key topics – age structure; gender balance; health; population change; population total/ dispersal) Objective 6: Supporting community empowerment 16 (Includes key topics – community decision-making; control of natural resources; access to funds, information, skills, education, expertise) Objective 7: Ensuring Equal access to employment 18 (Includes key topics – range/ dispersal of jobs; training; childcare provision; employment levels; skills base; business start-up) Objective 8: Ensuring equal access to essential services 20 (Includes key topics – housing; utilities; -

Isle of Barra - See Map on Page 8

Isle of South Uist - see map on Page 8 65 SOUTH UIST is a stunningly beautiful island of 68 crystal clear waters with white powder beaches to the west, and heather uplands dominated by Beinn Mhor to the east. The 20 miles of machair that runs alongside the sand dunes provides a marvellous habitat for the rare corncrake. Golden eagles, red grouse and red deer can be seen on the mountain slopes to the east. LOCHBOISDALE, once a major herring port, is the main settlement and ferry terminal on the island with a population of approximately Visit the HEBRIDEAN JEWELLERY shop and 300. A new marina has opened, and is located at the end of the breakwater with workshop at Iochdar, selling a wide variety of facilities for visiting yachts. Also newly opened Visitor jewellery, giftware and books of quality and Information Offi ce in the village. The island is one of good value for money. This quality hand crafted the last surviving strongholds of the Gaelic language jewellery is manufactured on South Uist in the in Scotland and the crofting industries of peat cutting Outer Hebrides. and seaweed gathering are still an important part of The shop in South Uist has a coffee shop close by everyday life. The Kildonan Museum has artefacts the beach, where light snacks are served. If you from this period. ASKERNISH GOLF COURSE is the are unable to visit our shop, please visit us on our oldest golf course in the Western Isles and is a unique online store. Tel: 01870 610288. HS8 5QX. -

34 MYRIAPODS on the OUTER HEBRIDES Gordon B Corbet Little

BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH MYRIAPOD AND ISOPOD GROUP Volume 20 2004 MYRIAPODS ON THE OUTER HEBRIDES Gordon B Corbet Little Dumbarnie, Upper Largo, Leven, Fife, KY8 6JG. INTRODUCTION Published records of myriapods from the Outer Hebrides are scanty and are summarised in three sources. Waterston (1981) recorded 15 species, with a list of islands from which each had been recorded. This incorporated records from Barra in 1935 reported by Waterston (1936). The provisional atlases (British Myriapod Group, 1988 for millipedes, Barber & Keay, 1988 for centipedes) recorded seven species, adding two to the total, but did not claim to be comprehensive with regard to earlier published records. In addition there are unpublished records of millipedes rising from a survey of invertebrates conducted in 1976 by the Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE, 1979). This included pitfall-trapping at 18 sites on Lewis/Harris, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist, but produced only Cylindroiulus latestriatus (at every site), plus a single Polydesmus inconstans on North Uist. I visited the Outer Hebrides from 3rd to 13th June 2003 and recorded myriapods on the following islands: Lewis/Harris, Great Bernera (bridged), Scalpay (bridged), South Uist, Eriskay (bridged), Barra and Vatersay (bridged). Recording was solely by hand searching in leaf-litter and under stones, wood and refuse. The general impression was that myriapods were scarce, with a large proportion of turned stones revealing nothing. In contrast earwigs, Forficula auricularia were unusually abundant. MILLIPEDES Waterston (1981) recorded six species, including one, Cylindroiulus britannicus, from St Kilda only. The provisional atlas recorded four species post-1970 adding Ophyiulus pilosus. -

02 North Uist and Berneray Coastal Area Version

SECTION 3: MAIN CATCHMENTS, COASTAL AREAS & SURFACE WATER MANAGEMENT WITHIN OUTER HEBRIDES LOCAL PLAN DISTRICT CHAPTER 4.3: COASTAL FLOODING North Uist and Berneray Coastal Area Local Plan D istrict Local Authority Outer Hebrides - 02 Comhairle nan Eilean Siar The North Uist and Berneray Coastal Area (Figure 1) has a coastline with a length of approximately 350km. It comprises the islands of North Uist and Berneray which form the central part of the Outer Hebrides Local Plan District (LPD). This coastal area contains two of the eight Potentially Vulnerable Areas (PVAs) in the Outer Hebrides: Lochmaddy & Trumisgarry (PVA 02/04); and North Uist (PVA 02/05). The coastline is typically embayed with inlets and sea lochs particularly on the east and south coast. On the north and west coasts machair grasslands are the predominant land form extending to around 2 kilometres inland from the foreshore. The majority of settlements are located close to the coastline while others are situated at the landward limit of the machair where it joins with inland land forms such as glacial deposits, rock or peat. 02 North Uist and Berneray coastal area Page 1 of 11 Version 1.0 Figure 1: North Uist and Berneray Coastal Area 02 North Uist and Berneray coastal area Page 2 of 11 Version 1.0 4.3.1 Coastal Flooding Impacts Main urban centres and infrastructure at risk There are between 11 and 50 residential properties and less than 10 non-residential properties at medium to high risk of coastal flooding. Approximately 42% of properties at medium to high risk are located within the PVAs. -

Sustainable Transport for Remote Island Communities

STAR 2019 Thomas Schönberger Sustainable Transport for Remote Island Communities Thomas Schönberger and Neil Ferguson, University of Strathclyde, Colin Young, Argyll and Bute Council, and Derek Halden, Derek Halden Consultancy Ltd. 1 Introduction This paper outlines ways to make remote island communities in Western Scotland more accessible, while aiming for options with minimal CO2 emissions to contribute to Scotland’s intended transition to a low carbon economy. The underlying analysis considers current policy challenges to provide more frequent connections to remote island communities in response to a growing public need for better accessibility while at the same time becoming less reliant on public subsidies for supporting sustainable growth on remote Scottish Islands. These challenges are analysed based on experiences in Argyll and Bute Council in Western Scotland to then serve as a basis for similar discussions in other areas with scheduled ferry and air services in Western Scotland and across the world. 2 Background In recent years the majority of the remote island communities in Scotland have grown in population size. Table 1 presents the Census data of 2001 and 2011 and shows that in this period the population on some islands in Western Scotland has grown significantly. For Argyll and Bute, the 2011 Census identified that approximately 17.7 per cent of the population in the Council area live on the populated islandsi. Table 1: Population Development of selected Islands in Western Scotland according to the 2001 and 2011 Census % -

The Western Isles of Lewis, Harris, Uists, Benbecula and Barra

The Western Isles of Lewis, Harris, Uists, Benbecula and Barra 1 SEATREK is based in Uig on 5 UIG SANDS RESTAURANT is a newly Let the adventure begin! Lewis, one of the most beautiful opened licensed restaurant with spectacular locations in Britain. We offer views across the beach. Open for lunches unforgettable boat trips around and evening meals. Booking essential. the Hebrides. All welcome, relaxed atmosphere and family Try any of our trips for a great friendly. Timsgarry, Isle of Lewis HS2 9ET. family experience with the Tel: 01851 672334. opportunity of seeing seals, Email: [email protected] basking sharks, dolphins and www.uigsands.co.uk many species of birds. DOUNE BRAES HOTEL: A warm welcome awaits you. We especially 6 Leaving from Miavaig Seatrek RIB Short Trips cater for ‘The Hebridean Way’ for cyclists, walkers and motorcyclists. Harbour, Uig, Isle of Lewis. We have safe overnight storage for bicycles. We offer comfortable Tel: 01851 672469. Sea Eagles & Lagoon Trip .............................. 2 hours accommodation, light meals served through the day and our full www.seatrek.co.uk Island Excursion ................................................. 3 hours evening menu in the evening. Locally sourced produce including Email: [email protected] Customised Trips ............................................... 4 hours our own beef raised on our croft, shellfi sh and local lamb. There’s a Fishing Trip ........................................................... 2 hours Gallan Head Trip ................................................. 2 hours good selection of Malt Whiskies in the Lounge Bar or coffees to go Sea Stacks Trip ................................................... 2 hours whilst you explore the West Side of the Island. Tel: 01851 643252. Email: [email protected] www.doune-braes.co.uk 2 SEA LEWIS BOAT TRIPS: Explore the 7 BLUE PIG CREATIVE SPACE: coastline North and South of Stornoway Carloway’s unique working studio and in our 8.5m Rib. -

A Late Norse Church in South Uist 333

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 122 (1992), 329-350 Cille Donnain lata : e Norse churc Soutn hi h Uist Andrew Fleming Ale*& x Woolf* ABSTRACT On a promontory on the western edge of Loch Kildonan, South Uist, in the Western Isles, are the ruins of a church known as Cille Donnain. The paper argues that this church and some buildings nearbythe on Eilean Mor (reached causeways)by constituted importantan 12th-century religious and political centre, comparable to Finlaggan in Islay; it is suggested that the site may have been the seat of a bishop. The church lies within an earlier dun-like site, which is also described, with suggestions about earlier loch levels here. INTRODUCTION The site described here lies on what is now a promontory on the western edge of upper Loch Kildonan (NGR NF 731 282). It is about 2 km south-east of Rubha Ardvule, the most conspicuous headlan wese th tn dcoaso Soutf to h Uist (illus }-4). The site is known to local people, and was marked on the first edition (1881) of the 6-inch Ordnance Survey map as 'Cille Donnain' (in Gothic lettering) and 'Ancient Burial Ground (disused)' t appearI currene . th n o se aret s th 'Cill1:10,00a f o ep Donnai0ma n (site of)'. However RCAHMe th , S volumaree th ar reporteefo d that 'n obuildiny tracvisiblean w f eno o s gi ' (1928, 120) Royae Th . l Commission's investigator visite aree dth a onl day8 y1 s afte outbreae th r k of the First World War, so his mind may have been on other matters. -

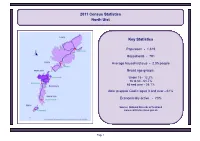

2011 Census Statistics North Uist Key Statistics

2011 Census Statistics North Uist Key Statistics Population - 1,619 Households - 791 Average household size - 2.05 people Broad age groups: Under 16 - 12.2% 16 to 64 - 61.7% 65 and over - 26.1% Able to speak Gaelic aged 3 and over - 61% Economically active - 70% Source: National Records of Scotland www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk Page 1 Population Outer Hebrides 2011 North Uist 2011 Number Percentage Number Percentage Age structure in North Uist and Outer Hebrides 2011 0 to 4 1,354 4.9 62 3.8 5 to 7 847 3.1 33 2.0 30.0 8 to 9 566 2.0 23 1.4 25.0 10 to 14 1,529 5.5 63 3.9 15 382 1.4 16 1.0 20.0 16 to 17 669 2.4 47 2.9 15.0 18 to 19 535 1.9 27 1.7 10.0 20 to 24 1,228 4.4 68 4.2 25 to 29 1,258 4.5 53 3.3 5.0 30 to 44 5,068 18.3 242 14.9 0.0 45 to 59 6,105 22.1 426 26.3 60 to 64 2,174 7.9 136 8.4 Percentage of Population 65 to 74 3,197 11.5 236 14.6 75 to 84 1,987 7.2 136 8.4 85 to 89 539 1.9 38 2.3 90 and over 246 0.9 13 0.8 Outer Hebrides North Uist All people 27,684 100.0 1,619 100.0 Age Structure Marital Status Marital Status in North Uist As with other island areas Out of the 1,422 people Single the highest percentage of aged 16 and over in North people is to be found in Uist, the largest group 1.5 8.5 Married the 45 to 59 age group, 10.5 (47%) were married.