Reactions to the Seventh-Day Adventist Evangelical Conferences and Questions on Doctrine 1955-1971

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos Marcelo Eduardo da Costa Dias Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Costa Dias, Marcelo Eduardo da, "An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos" (2016). Dissertations. 1598. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS by Marcelo E. C. Dias Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS Name of researcher: Marcelo E. C. Dias Name and degree of faculty chair: Bruce Bauer, DMiss Date completed: May 2016 In a little over 100 years, the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Brazil has grown to a membership of 1,447,470 (December 2013), becoming the country with the second highest total number of Adventists in the world. Very little academic research has been done to study or analyze the growth and development of the Adventist church in Brazil. -

Southwest Bahia Mission Facade, 2019

Southwest Bahia Mission facade, 2019. Photo courtesy of Nesias Joaquim dos Santos. Southwest Bahia Mission NESIAS JOAQUIM DOS SANTOS Nesias Joaquim dos Santos The Southwest Bahia Mission (SWBA) is an administrative unit of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) located in the East Brazil Union Mission. Its headquarters is in Juracy Magalhães Street, no. 3110, zip code 45023-490, district of Morada dos Pássaros II, in the city of Vitoria da Conquista, in Bahia State, Brazil.1 The city of Vitória da Conquista, where the administrative headquarters is located, is also called the southwestern capital of Bahia since it is one of the largest cities in Bahia State. With the largest geographical area among the five SDA administrative units in the State of Bahia, SWBA operates in 166 municipalities.2 The population of this region is 3,943,982 inhabitants3 in a territory of 99,861,370 sq. mi. (258,639,761 km²).4 The mission oversees 42 pastoral districts with 34,044 members meeting in 174 organized churches and 259 companies. Thus, the average is one Adventist per 116 inhabitants.5 SWBA manages five schools. These are: Escola Adventista de Itapetinga (Itapetinga Adventist School) in the city of Itapetinga with 119 students; Colégio Adventista de Itapetinga (Itapetinga Adventist Academy), also in Itapetinga, with 374 students; Escola Adventista de Jequié (Jequié Adventist School) with 336 students; Colégio Adventista de Barreiras (Barreiras Adventist Academy) in Barreiras with 301 students; and Conquistense Adventist Academy with 903 students. The total student population is 2,033.6 Over the 11 years of its existence, God has blessed this mission in the fulfillment of its purpose, that is, the preaching of the gospel to all the inhabitants in the mission’s territory. -

C:\WW Manuscripts\Back Issues\11-3 Lutheranism\11

Word & World 11/3 (1991) Copyright © 1991 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 276 A North American Perspective TODD W. NICHOL Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, Saint Paul, Minnesota Thirty years ago, historian Winthrop Hudson called Lutheranism the last, best hope of Protestantism in the United States. Insularity, Hudson said in his widely read study American Protestantism, had protected Lutherans from the theological disintegration and lack of connection to historical tradition he thought characteristic of most other American Protestants. As Hudson saw it, a history of more or less intentional parochialism had given Lutherans specific advantages that could put them in the vanguard of a Protestant renewal in the United States: the effect of impending mergers, rising membership, a confessional tradition, liturgical practice, and a sense of community based in part on sociological factors.1 A generation later, however, it appears that Hudson missed his guess. In the last three decades, questions regarding merger and membership, theology and worship, and the contours of community have troubled and sometimes divided American Lutherans. That these things matter to some Lutherans is, of course, evidence that Winthrop Hudson’s optimistic assessment of Lutheranism in the United States was not entirely without basis. Yet few knowledgeable Lutherans in 1991 would be prepared to claim that their churches have taken the leading role in a renewal of Protestantism in North America or that they are now in a position to do so. American Lutheranism is now more difficult to assess than even so distinguished an historian of American religion as Winthrop Hudson was able to predict thirty years ago. -

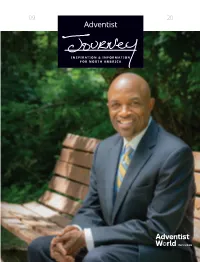

Adventist Journey 09/20

09 20 INSPIRATION & INFORMATION FOR NORTH AMERICA INCLUDED Adventist Journey Contents 04 Feature 13 Perspective Meet the New NAD President Until All Lives Matter . 08 NAD News Briefs My Journey In my administrative role at the NAD, I still do evangelism. I do at least one [series] a year and I still love it. Sometimes, through all the different committees and policies and that part of church life, you have to work to keep connected to the front-line ministries—where people are being transformed by the power of the gospel. Visit vimeo.com/nadadventist/ajalexbryant for more of Bryant’s story. G. ALEXANDER BRYANT, new president of the North American Division Cover Photo by Dan Weber Dear Reader: The publication in your hands represents the collaborative efforts of the ADVENTIST JOURNEY North American Division and Adventist World magazine, which follows Adventist Journey Editor Kimberly Luste Maran (after page 16). Please enjoy both magazines! Senior Editorial Assistant Georgia Damsteegt Art Direction & Design Types & Symbols Adventist Journey (ISSN 1557-5519) is the journal of the North American Division of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. The Northern Asia-Pacific Division of the General Conference of Seventh-day Consultants G. Earl Knight, Mark Johnson, Dave Weigley, Adventists is the publisher. It is printed monthly by the Pacific Press® Publishing Association. Copyright Maurice Valentine, Gary Thurber, John Freedman, © 2020. Send address changes to your local conference membership clerk. Contact information should be available through your local church. Ricardo Graham, Ron C. Smith, Larry Moore Executive Editor, Adventist World Bill Knott PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. -

The Evangelical Catholic Part 2

THE WAY PART 2 THE EVANGELICAL CATHOLIC SMALL GROUP USER GUIDE ® Copyright © 2019 The Evangelical Catholic All rights reserved. Published by The Word Among Us Press 7115 Guilford Drive, Suite 100 Frederick, Maryland 21704 wau.org 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN: 978-1-59325-353-0 eISBN: 978-1-59325-369-1 Nihil Obstat: Msgr. Michael Morgan, J.D., J.C.L. Censor Librorum September 19, 2019 Imprimatur: +Most Rev. Felipe J. Estevez, S.T.D. Diocese of St. Augustine September 19, 2019 Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are taken from The Catholic Edition of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1965, 1966 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America opyright © 1994, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops—Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Cate- chism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops—Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Used with permission. Unless otherwise noted, papal and other Church documents are quoted from the Vatican website, vatican.va. Cover design by Austin Franke Interior design by Down to Earth Design No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the author and publisher. -

Vessenger: It's Strengths and Weaknesses Editorial NOT STRONG ENOUGH

11 r el in r OSOVO RECORD1 .1 U 2 4 1 9 9 9 In this issue Sanitarium looks for performance Taking liberties Atoffi outreach I stretches resources essenger of the LOrd The Prophetic Ministry Ellen G. White I HERBERT E• DOUGLASS Vessenger: It's strengths and weaknesses editorial NOT STRONG ENOUGH osovo. What has happened the church during the 1260 years and remains loyal in their allegiance there has shocked the world. known as the Dark Ages; and the to God. KThe full extent of the horren- devil's aggression at the end of time This account in Revelation 12 dous acts of brutality in the Balkans against those who, by their lives, assures God's people that goodness are only now beginning to unfold. demonstrate the "faith of Jesus." will triumph over evil. In the cosmic This has been a graphic demonstra- Despite the turmoil portrayed, this warfare in which God's people are a tion of evil and hatred in these sup- chapter underscores the "good news," part, Michael is on our side. posedly enlightened times. Once that the dominance of the devil was The time is coming when it will be again questions are raised about the to be challenged and broken. In spite demonstrated finally before the uni- nature of evil, of suffering and God's of his guile and power he is "not verse that the devil is not strong sovereignty and power. strong enough" to prevail (verse 8, enough to hold a single person who In a world where there is often lit- NIV). -

With This Issue ADVENTIST WORLD

ADVENTISTwith this FREEWORLD issue ollowing the earthquake tragedy that struck South Asia, ADRA-UK has launched an appeal to raise funds to bring immediate relief to the victims. ADRA-UK is 95% of the buildings in Bagh were co-ordinating its efforts with demolished by the quake Fother donor offices and ADRA- Trans-Europe to respond to this major disaster. The ADRA network is focusing efforts on Pakistan, which has been most affected by the disaster. ADRA has had a long-term presence in Pakistan, providing development proj- ects in the affected regions since 1984. The ADRA-Pakistan office has already commenced relief activities with the provision of food, medical supplies and shelter. The ADRA network was mobilised into action within hours of the earthquake, which occurred at 8:50 on Saturday 8 October, and measured 7.6 on the Richter Scale. The writer was in contact with ADRA-International and Trans- Europe (which covers Pakistan as one of its field territories) by > 16 It takes a great man to deal with failure and time to make sure I had not Christmas shoebox defeat. It takes a very, very great man to deal with misread something. No. There success and victory. David was not that great. it was. I read as far as verse I Victorious over the Syrians, military genius 15 where it says that Nathan David felt so confident about capturing Rabbah ‘went home’, and I thought, appeal (Amman) that he sent Joab to do it while he stayed ‘Right, that’s it’; and I lost Is God All boxes need to be received by 1 December in home. -

20 Changing American Evangelical Attitudes Towards

Changing American Evangelical Attitudes towards Roman Catholics: 1960-2000 Don Sweeting Don Sweeting is Senior Pastor of Introduction summing up forty years of evangelicalism Cherry Creek Presbyterian Church, in In 1960, Presidential campaign historian since 1945, Bayly said, “We inherited a Englewood, Colorado. He has also Theodore H. White observed that “the Berlin Wall between evangelical Chris- served as the founding pastor of the largest and most important division in tians and Roman Catholics; we bequeath Chain of Lakes Community Bible Church American society was that between Prot- a spirit of love and rapprochement on in Antioch, Illinois. Dr. Sweeting was estants and Catholics.”1 As a vital part of the basis of the Bible rather than fear and educated at Moody Bible Institute, American Protestant life, evangelicalism hatred.”7 Lawrence University, Oxford University reflected the strains of this conflict.2 Anti- By the mid 1990s, it was clear that atti- (M.A.), and Trinity Evangelical Divinity Catholicism, according to church historian tudes were changing. On a local level, School (Ph.D.) where he wrote his dis- George Marsden, “was simply an unques- evangelicals and Catholics were meeting sertation on the relationship between tioned part of the fundamentalist- to discuss issues from poverty and wel- evangelicals and Roman Catholics. evangelicalism of the day.”3 fare reform to abortion. On the national This posture of outright public hostil- level changes were also apparent. Evan- ity was evidenced in many ways. It could gelical publishing houses were printing be seen in the opposition of many evan- books by Catholic authors. Some evangeli- gelical leaders to the presidential candi- cal parachurch ministries began placing dacy of John F. -

Avondale Announces New Scholarships

December 3, 1994 RECOR Week of Prayer Leads to Decisions-10 Avondale Announces New Scholarships fifty scholarships worth $A2000 each will be available in 1995 to provide financial assistance to FAvondale College, NSW, students disadvantaged by the drought or other hardships. The An Urgent Need scholarships will be applied to residential fees. for Medical "Some scholarships will be available to returning students and others assigned to new students," says the Avondale public relations officer, Dr Lyell Heise. "Prospective students who Staff-6 can demonstrate genuine financial need should contact the student finance office immediately for details on how to establish eligibility." The student finance office can be contacted on (049) 77 1107 or on free phone 1800 804 324. Does God Have "There will be an assessment of need, and some academic criteria to be met," says Dr Heise. "Avondale is looking forward to hearing from students who can benefit from this new initiative." a Gender Pictured are students currently attending Avondale. Bias? EDITORIAL Priority and Urgency The result is that we generally don't had prepared 10 people, with more , write make personal witnessing and involve- than 50 preparing at least 80 people in A'm ex- ment a priority—or even an urgency. the last four years. periencing the We pray for the Holy Spirit to accom- Why are these results in Mexico, and Fourth Internat- plish in our land, what is happening in not in New Zealand and Australia? ional Congress Inter- and South America, the It isn't because the work is easy in of Laity, being Philippines, Africa and Russia. -

LUTHER, MARGUERITE DE NAVARRE, and the EVANGELICAL NARRATIVE CATHARINE RANDALL Fordha

TABLEAUX VIVANTS AND TEXTUAL RESURRECTION: LUTHER, MARGUERITE DE NAVARRE, AND THE EVANGELICAL NARRATIVE CATHARINE RANDALL Fordham University A THEATEROF TESTIMONIALTEXTS Greek word for gospel, evangelion, comes from the same root as that Thefor "gossip" attesting that telling stories to narrate the Christian experience is a time-honored, and etymologically-appropriate, theological and literary strategy. However, in the decades prior to the Reformation, Catholic preaching had become increasingly centered in parabiblical texts, with friars drawing examples of heroic faith from the Golden Legend and the Lives of the Saints with greater frequency than they had recourse to the Biblel. One of the greatest contributions of Martin Luther and the evangelicals who followed him was to reinstate the Bible, and its treasure-chest of inspirational narratives, at the heart both of the individual believer's spiritual experience and of the community of the Christian church. Telling stories was thus a foundational tool in Reformation theology and ecclesiology, a textual strategy to confess the power of the Lord and, as though penning a plot, to trace His workings in human lives. This new evangelical dramatization rehearses vivid tableaux vivants, vignettes in which individuals describe their walk with God, highlighting their particular way of experiencing and perceiving the salvation narrative'. These evangelical evocations rely most heavily on New Testament writings: they gos- sip about the Gospels. Protestants initiated a new way of talking about sins; they encouraged a group confession, to be recited in church, in the presence of fellow believers and fellow sinners. They gave voice to the sin, dramatizing it in a kind of community theater, rendering it both more individual (each man was responsible for his own sin; no priest or intermediary presumed to absolve him) and more communal (in that the naming of the sin required the presence of a multitude of others as witnesses). -

The Holy Trinity and Our Lutheran Liturgy Timothy Maschke

Volume 67:3/4 July/October 2003 Table of Contents ~ -- -- - Eugene F. A. Klug (1917-2003) ........................ 195 The Theological Symposia of Concordia Theological Seminary (2004) .................................... 197 Introduction to Papers from the 2003 LCMS Theological Prof essorsf Convocation L. Dean Hempelmann ......................... 200 Confessing the Trinitarian Gospel Charles P. Arand ........................ 203 Speaking of the Triune God: Augustine, Aquinas, and the Language of Analogy John F. Johnson ......................... 215 Returning to Wittenberg: What Martin Luther Teaches Today's Theologians on the Holy Trinity David Lumpp .......................... 228 The Holy Trinity and Our Lutheran Liturgy Timothy Maschke ....................... 241 The Trinity in Contemporary Theology: Questioning the Social Trinity Norman Metzler ........................ 270 Teaching the Trinity David P. Meyer ......................... 288 The Bud Has Flowered: Trinitarian Theology in the New Testament Michael Middendorf ..................... 295 The Challenge of Confessing and Teaching the Trinitarian Faith in the Context of Religious Pluralism A. R. Victor Raj ......................... 308 The Doctrine of the Trinity in Biblical Perspective David P. Scaer .......................... 323 Trinitarian Reality as Christian Truth: Reflections on Greek Patristic Discussion William C. Weinrich ..................... 335 The Biblical Trinitarian Narrative: Reflections on Retrieval Dean 0. Wenthe ........................ 347 Theological Observer -

Ellen White's Counsel to Leaders: Identification and Synthesis of Principles, Experiential Application, and Comparison with Current Leadership Literature

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Professional Dissertations DMin Graduate Research 2006 Ellen White's Counsel To Leaders: Identification And Synthesis Of Principles, Experiential Application, And Comparison With Current Leadership Literature Cynthia Ann Tutsch Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Tutsch, Cynthia Ann, "Ellen White's Counsel To Leaders: Identification And Synthesis Of Principles, Experiential Application, And Comparison With Current Leadership Literature" (2006). Professional Dissertations DMin. 372. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/372 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Dissertations DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT ELLEN WHITE’S COUNSEL TO LEADERS: IDENTIFICATION AND SYNTHESIS OF PRINCIPLES, EXPERIENTIAL APPLICATION, AND COMPARISON WITH CURRENT LEADERSHIP LITERATURE by Cynthia Ann Tutsch Adviser: Denis Fortin ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: ELLEN WHITE’S COUNSEL TO LEADERS: IDENTIFICATION AND SYNTHESIS OF PRINCIPLES, EXPERIENTIAL APPLICATION AND COMPARISON WITH CURRENT LEADERSHIP LITERATURE’ Name of researcher: Cynthia Ann Tutsch Name and degree of faculty adviser: Denis Fortin, Ph.D. Date completed: December 2006 Ellen G. White’s counsel to leaders on both spiritual and practical themes, as well as her personal application of that counsel, has on-going relevance in the twenty-first century. The author researched secondary literature, and Ellen G. White’s published and unpublished works.