The Search for Knowledge Among the Seventh-Day Adventists in the Area of Maroantsetra, Madagascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan Agriculture and Land Growth Management Project (P151469) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: Original: January 2016 – Revision PP: December 2016 – February 2017 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: - 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: July 2016 to December 2017 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable Public Disclosure Authorized procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Type de contrats Montant contrat Méthode de passation de Contrat soumis à revue a en US$ (seuil) marchés priori de la banque 1. Travaux ≥ 5.000.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 5.000.000 AON Selon PPM < 500.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Public Disclosure Authorized Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats 2. Fournitures ≥ 500.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 500.000 AON Selon PPM < 200.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats Tout montant Marchés passes auprès Tous les contrats d’institutions de l’organisation des Nations Unies Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guidelines. July 9, 2010 3. Proposed Procedures for CDD Components (as per paragraph. 3.17 of the Guidelines: - 4. Reference to (if any) Project Operational/Procurement Manual: Manuel de procedures (execution – procedures administratives et financières – procedures de passation de marches): décembre 2016 – émis par l’Unite de Gestion du projet Casef (Croissance Agricole et Sécurisation Foncière) 5. -

Developments in the Relationship Between Seventh Day Baptists and Seventh-Day Adventists, 1844•Fi1884

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 55, No. 2, 195–212. Copyright © 2017 Andrews University Seminary Studies. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SEVENTH DAY BAPTISTS AND SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTISTS, 1844–1884 Michael W. Campbell Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies Silang, Cavite, Philippines Abstract This paper reviews the complex relationship between two Sabbatarian denominations: Seventh Day Baptists and Seventh-day Adventists. The primary point of contact was through the Seventh Day Baptist, Rachel Oaks Preston, who shared her Sabbatarian views during the heyday of the Millerite revival. Later, after the Great Disappointment, one such post-disappointment group emerged with a distinctive emphasis upon the seventh-day Sabbath. These Sabbath-keeping Adventists, organized in 1863 as the Seventh-day Adventist Church, established formal relations with Seventh Day Baptists between 1868 and 1879 through the exchange of delegates who identified both commonalities as well as differences. Their shared interest in the seventh-day Sabbath was a strong bond that, during this time, helped each group to look beyond their differences. Keywords: Seventh Day Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, Adventists, interfaith dialogue Introduction1 Seventh Day Baptists and Seventh-day Adventists share a fundamental conviction that the seventh-day Sabbath is the true biblical Sabbath. Each tradition, although spawned two centuries apart, argues that, soon after the New Testament period, the Christian church began to worship on Sunday rather than continue to observe the Jewish Sabbath. Both groups teach that the original Sabbath was the seventh day, instituted at Creation and affirmed when God gave the Ten Commandments. Each tradition developed their view of the Sabbath during a time of chaos in which religious figures sought to return to what they believed was an earlier, purer form of Christianity. -

Regional Conferences in the Seventh-Day Adventist

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2009 [Black] Regional Conferences in the Seventh-Day Adventist (SDA) Church Compared with United Methodist [Black] Central Jurisdiction/Annual Conferences with White SDA Conferences, From 1940 - 2001 Alfonzo Greene, Jr. Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Jr., Alfonzo, "[Black] Regional Conferences in the Seventh-Day Adventist (SDA) Church Compared with United Methodist [Black] Central Jurisdiction/Annual Conferences with White SDA Conferences, From 1940 - 2001" (2009). Dissertations. 160. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/160 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2009 Alfonzo Greene, Jr. LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO [BLACK] REGIONAL CONFERENCES IN THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH (SDA) COMPARED WITH UNITED METHODIST [BLACK] CENTRAL JURISDICTION/ANNUAL CONFERENCES WITH WHITE S.D.A. CONFERENCES, FROM 1940-2001 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY ALFONZO GREENE, JR. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER -

An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2016 An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos Marcelo Eduardo da Costa Dias Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Costa Dias, Marcelo Eduardo da, "An Analysis of Adventist Mission Methods in Brazil in Relationship to a Christian Movement Ethos" (2016). Dissertations. 1598. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS by Marcelo E. C. Dias Adviser: Bruce Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: AN ANALYSIS OF ADVENTIST MISSION METHODS IN BRAZIL IN RELATIONSHIP TO A CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT ETHOS Name of researcher: Marcelo E. C. Dias Name and degree of faculty chair: Bruce Bauer, DMiss Date completed: May 2016 In a little over 100 years, the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Brazil has grown to a membership of 1,447,470 (December 2013), becoming the country with the second highest total number of Adventists in the world. Very little academic research has been done to study or analyze the growth and development of the Adventist church in Brazil. -

Southwest Bahia Mission Facade, 2019

Southwest Bahia Mission facade, 2019. Photo courtesy of Nesias Joaquim dos Santos. Southwest Bahia Mission NESIAS JOAQUIM DOS SANTOS Nesias Joaquim dos Santos The Southwest Bahia Mission (SWBA) is an administrative unit of the Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) located in the East Brazil Union Mission. Its headquarters is in Juracy Magalhães Street, no. 3110, zip code 45023-490, district of Morada dos Pássaros II, in the city of Vitoria da Conquista, in Bahia State, Brazil.1 The city of Vitória da Conquista, where the administrative headquarters is located, is also called the southwestern capital of Bahia since it is one of the largest cities in Bahia State. With the largest geographical area among the five SDA administrative units in the State of Bahia, SWBA operates in 166 municipalities.2 The population of this region is 3,943,982 inhabitants3 in a territory of 99,861,370 sq. mi. (258,639,761 km²).4 The mission oversees 42 pastoral districts with 34,044 members meeting in 174 organized churches and 259 companies. Thus, the average is one Adventist per 116 inhabitants.5 SWBA manages five schools. These are: Escola Adventista de Itapetinga (Itapetinga Adventist School) in the city of Itapetinga with 119 students; Colégio Adventista de Itapetinga (Itapetinga Adventist Academy), also in Itapetinga, with 374 students; Escola Adventista de Jequié (Jequié Adventist School) with 336 students; Colégio Adventista de Barreiras (Barreiras Adventist Academy) in Barreiras with 301 students; and Conquistense Adventist Academy with 903 students. The total student population is 2,033.6 Over the 11 years of its existence, God has blessed this mission in the fulfillment of its purpose, that is, the preaching of the gospel to all the inhabitants in the mission’s territory. -

The Puritan Roots of Seventh-Day Adventist Belief

BOOK REVIEWS Ball, Bryan W. The English Connection: The Puritan Roots of Seventh- day Adventist Belief. Cambridge, Eng. : James Clarke/Greenwood, S.C.: Attic Press. 1981. 252 pp. $15.95 (in England, £7.50). The English Connection is an excellent analysis of "Puritan religious thought, in its broadest sense," which Ball believes "gave to the English- speaking world all the essentials of contemporary Adventist belief" (p. 3). Although treating a complex subject in an encyclopedic fashion, it is a very well-organized and lucid work that not only allows the Puritans of the late sixteenth through early eighteenth century to speak for themselves by drawing upon numerous quotations from Puritan divines, preachers, and polemicists, but also synthesizes and interprets for the general reader the more difficult aspects of Puritan theology. After a brief survey of the history of Puritanism, the study concentrates on specific key doctrines, each discussed thematically rather than chrono- logically, in the light of specific Puritan writings and in association with related beliefs. These key beliefs are encapsulated in the book's chapter titles: "The Sufficiency of Scripture," "This Incomparable Jesus," "The Lord Our Righteousness," "The New Man," "Believer's Baptism," "A High Priest in Heaven," "Gospel Obedience," "The Seventh-Day Sab- bath," "The Whole Man," "The Return of Christ," "The Great Almanack of Prophecy," and "The World to Come." In his introduction, Ball states that his purpose is "to examine specific doctrines" that show how "in its essentials, Seventh-day Adventist belief had been preached and practised in England during the Puritan era" (p. 2). A related purpose is to disprove those who see Adventism as "deviant" and to "demonstrate Adventism's essential affinity with historic, biblical Protestantism as opposed to any superficial relationship to nineteenth-century pseudo-Christian sectarianism" (p. -

The Person of Christ in the Seventh–Day Adventism: Doctrine–Building and E

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Butoiu, Nicolae (2018) The person of Christ in the Seventh–day Adventism: doctrine–building and E. J. Wagonner’s potential in developing christological dialogue with eastern Christianity. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/24350/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Seventh-Day Adventism, Doctrinal Statements, and Unity

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 27/1-2 (2016): 98-116. Article copyright © 2016 by Michael W. Campbell. Seventh-day Adventism, Doctrinal Statements, and Unity Michael W. Campbell Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies Cavite, Philippines 1. Introduction “All Christians engage in confessional synthesis,” wrote theologian Carl R. Trueman.1 Some religious groups adhere to a public confession of faith as subject to public scrutiny whereas others are immune to such scrutiny. Early Seventh-day Adventists, with strong ties to the Christian Connexion, feared lest the creation of a statement of beliefs so that some at some point may disagree with that statement may at some point be excluded.2 Another danger was that statements of belief might be used to present making new discoveries from Scripture, or afterward a new truth might be stifled by appealing to the authority of an already established creed. From the perspective of early Sabbatarian Adventists, some remembered the time when during the Millerite revival that statements of belief were used to exclude them from church fellowship.3 These fears were aptly expressed during the earliest organizational developments in 1861 of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. According to denominational co-founder, James White: “making a creed is setting the stakes, and barring up the way to all future advancement. The Bible is 1 Carl R. Trueman, The Creedal Imperative (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012), 21. 2 Bert B. Haloviak, “Heritage of Freedom,” unpublished manuscript, 2. 3 George R. Knight, A Search for Identity: The Development of Seventh-day Adventist Beliefs (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald, 2000), 21-24. -

Candidats Fenerive Est Ambatoharanana 1

NOMBRE DISTRICT COMMUNE ENTITE NOM ET PRENOM(S) CANDIDATS CANDIDATS GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA 1 KOMPA Justin Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA 1 RAVELOSAONA Rasolo Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 SABOTSY Patrice Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 RAZAFINDRAFARA Elyse Emmanuel Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II 1 INDEPENDANT TELO ADRIEN (Telo Adrien) TELO Adrien AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT BOTOFASINA ANDRE (Botofasina FENERIVE EST 1 BOTOFASINA Andre MANANTSANTRANA Andre) AMPASIMBE GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST 1 VELONORO Gilbert MANANTSANTRANA Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) AMPASIMBE FENERIVE EST 1 GROUPEMENT DE P.P MTS (Malagasy Tonga Saina) ROBIA Maurille MANANTSANTRANA AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT KOESAKA ROMAIN (Koesaka FENERIVE EST 1 KOESAKA Romain MANANTSANTRANA Romain) AMPASIMBE INDEPENDANT TALEVANA LAURENT GERVAIS FENERIVE EST 1 TALEVANA Laurent Gervais MANANTSANTRANA (Talevana Laurent Gervais) GROUPEMENT DE P.P MMM (Malagasy Miara FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY 1 RABEFIARIVO Sabotsy Miainga) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY 1 CLOTAIRE Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) INDEPENDANT ROBERT MARCELIN (Robert FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA 1 ROBERT Marcelin Marcelin) GROUPEMENT DE P.P IRMAR (Isika Rehetra Miarka FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA 1 KOANY Arthur Amin'ny Andry Rajoelina) -

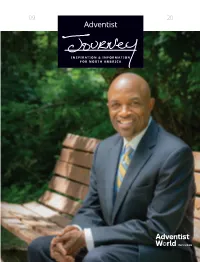

Adventist Journey 09/20

09 20 INSPIRATION & INFORMATION FOR NORTH AMERICA INCLUDED Adventist Journey Contents 04 Feature 13 Perspective Meet the New NAD President Until All Lives Matter . 08 NAD News Briefs My Journey In my administrative role at the NAD, I still do evangelism. I do at least one [series] a year and I still love it. Sometimes, through all the different committees and policies and that part of church life, you have to work to keep connected to the front-line ministries—where people are being transformed by the power of the gospel. Visit vimeo.com/nadadventist/ajalexbryant for more of Bryant’s story. G. ALEXANDER BRYANT, new president of the North American Division Cover Photo by Dan Weber Dear Reader: The publication in your hands represents the collaborative efforts of the ADVENTIST JOURNEY North American Division and Adventist World magazine, which follows Adventist Journey Editor Kimberly Luste Maran (after page 16). Please enjoy both magazines! Senior Editorial Assistant Georgia Damsteegt Art Direction & Design Types & Symbols Adventist Journey (ISSN 1557-5519) is the journal of the North American Division of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. The Northern Asia-Pacific Division of the General Conference of Seventh-day Consultants G. Earl Knight, Mark Johnson, Dave Weigley, Adventists is the publisher. It is printed monthly by the Pacific Press® Publishing Association. Copyright Maurice Valentine, Gary Thurber, John Freedman, © 2020. Send address changes to your local conference membership clerk. Contact information should be available through your local church. Ricardo Graham, Ron C. Smith, Larry Moore Executive Editor, Adventist World Bill Knott PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. -

1 COAG No. 72068718CA00001

COAG No. 72068718CA00001 1 TABLE OF CONTENT I- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 6 II- INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 III- MAIN ACHIEVEMENTS DURING QUARTER 1 ........................................................................................................... 10 III.1. IR 1: Enhanced coordination among the public, nonprofit, and commercial sectors for reliable supply and distribution of quality health products ........................................................................................................................... 10 III.2. IR2: Strengthened capacity of the GOM to sustainably provide quality health products to the Malagasy people 15 III.3. IR 3: Expanded engagement of the commercial health sector to serve new health product markets, according to health needs and consumer demand ........................................................................................................ 36 III.4. IR 4: Improved sustainability of social marketing to deliver affordable, accessible health products to the Malagasy people ............................................................................................................................................................. 48 III.5. IR5: Increased demand for and use of health products among the Malagasy people -

Boissiera 71

Taxonomic treatment of Abrahamia Randrian. & Lowry, a new genus of Anacardiaceae BOISSIERA from Madagascar Armand RANDRIANASOLO, Porter P. LOWRY II & George E. SCHATZ 71 BOISSIERA vol.71 Director Pierre-André Loizeau Editor-in-chief Martin W. Callmander Guest editor of Patrick Perret this volume Graphic Design Matthieu Berthod Author instructions for www.ville-ge.ch/cjb/publications_boissiera.php manuscript submissions Boissiera 71 was published on 27 December 2017 © CONSERVATOIRE ET JARDIN BOTANIQUES DE LA VILLE DE GENÈVE BOISSIERA Systematic Botany Monographs vol.71 Boissiera is indexed in: BIOSIS ® ISSN 0373-2975 / ISBN 978-2-8277-0087-5 Taxonomic treatment of Abrahamia Randrian. & Lowry, a new genus of Anacardiaceae from Madagascar Armand Randrianasolo Porter P. Lowry II George E. Schatz Addresses of the authors AR William L. Brown Center, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299, U.S.A. [email protected] PPL Africa and Madagascar Program, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299, U.S.A. Institut de Systématique, Evolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), UMR 7205, Centre national de la Recherche scientifique/Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle/École pratique des Hautes Etudes, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Sorbonne Universités, C.P. 39, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris CEDEX 05, France. GES Africa and Madagascar Program, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO, 63166-0299, U.S.A. Taxonomic treatment of Abrahamia (Anacardiaceae) 7 Abstract he Malagasy endemic genus Abrahamia Randrian. & Lowry (Anacardiaceae) is T described and a taxonomic revision is presented in which 34 species are recog- nized, including 19 that are described as new.