Perspectives Behind Translating House of Flesh by Yusuf Idris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam

Institute of Asian and African Studies at The Hebrew University The Max Schloessinger Memorial Foundation REPRINT FROM JERUSALEM STUDIES IN ARABIC AND ISLAM I 1979 THE MAGNES PRESS. THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY. JERUSALEM PROPHETS AND PROGENITORS IN THE EARLY SHI'ATRADITION* Uri Rubin INTRODUCTION As is well known, the Shi 'I belief that 'Ali' should have been Muhammad's succes- sor was based on the principle of hereditary Califate, or rather Imamate. 'Ali's father, Abu Talib, and Muhammad's father, 'Abdallah, were brothers, so that Muhammad and 'Ali were first cousins. Since the Prophet himself left no sons, the Shi 'a regarded' All as his only rightful successor.' Several Shi 'I traditions proclaim 'All's family relationship (qariiba) to Muhammad as the basis for his hereditary rights. For the sake of brevity we shall only point out some of the earliest.A number of these early Shi T traditions center around the "brothering", i.e. the mu'akhiih which took place after the hijra; this was an agreement by which each emigrant was paired with one of the Ansar and the two, who thus became brothers, were supposed to inherit each other (see Qur'an, IV, 33? 'All, as an exception, was paired not with one of the Ansar but with the Prophet himself." A certain verse in the Qur'an (VIII, 72) was interpreted as stating that the practice of mu iikhiin was confined only to the Muhajinin and the Ansar, to the exclusion of those believers who had stayed back in Mecca after the hijra. They re- tained the old practice of inheritance according to blood-relationship." This prac- tice, which was introduced in al-Madi na, affected the hereditary rights of the families of the Muhajiriin who were supposed to leave their legacy to their Ansari * This article is a revised form of a chapter from my thesis on some aspects of Muhammad's prophethood in the early literature of hadt th. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011

Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 Colorado Northwestern Community College Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 EDITOR ART EDITOR PRODUCTION/DESIGN Joe Wiley Elizabeth Robinson Denise Wade EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Ally Palmer Jinnah Schrock Rose Peterson Mary Slack Ariel Sanchez Michael Willie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The staff of Waving Hands Review thanks the following people: -CNCC President Russell George, his cabinet, the RJCD Board of Trustees, the MCAJCD Board of Control, and the CNCC Marketing Department for continued funding and support -All those who submitted work -All those who encouraged submissions Waving Hands Review, the literature and arts magazine of Colorado Northwestern Community College, seeks to publish exemplary works by emerging and established writers and artists of Northwest Colorado. Submissions in poetry, fiction, non-fiction, drama, photography, and art remain anonymous until a quality-based selection is made. Unsolicited submissions are welcome between September 1 and March 1. We accept online submissions only. Please visit the Waving Hands Review website at www.cncc.edu/waving_hands/ for detailed submission guidelines, or go to the CNCC homepage and click on the Waving Hands Review logo. Waving Hands Review is staffed by students of Creative Writing II. All works Copyright 2011 by individual authors and artists. Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 Table of Contents Artwork Yuri Chicovsky Cover Self-Portrait Janele Husband 17 Blanketed Deer Peter Bergmann 18 Winter -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

Darfur: Extra Judicial Execution of 168 Men

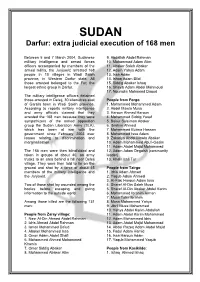

SUDAN Darfur: extra judicial execution of 168 men Between 5 and 7 March 2004, Sudanese 9. Abdallah Abdel Rahman military intelligence and armed forces 10. Mohammed Adam Atim officers accompanied by members of the 11. Abaker Saleh Abaker armed militia, the Janjawid, arrested 168 12. Adam Yahya Adam people in 10 villages in Wadi Saleh 13. Issa Adam province, in Western Darfur state. All 14. Ishaq Adam Bilal those arrested belonged to the Fur, the 15. Siddig Abaker Ishaq largest ethnic group in Darfur. 16. Shayib Adam Abdel Mahmoud 17. Nouradin Mohamed Daoud The military intelligence officers detained those arrested in Deleij, 30 kilometres east People from Forgo of Garsila town in Wadi Saleh province. 1. Mohammed Mohammed Adam According to reports military intelligence 2. Abdel Mawla Musa and army officials claimed that they 3. Haroun Ahmed Haroun arrested the 168 men because they were 4. Mohammed Siddig Yusuf sympathizers of the armed opposition 5. Bakur Suleiman Abaker group the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), 6. Ibrahim Ahmed which has been at war with the 7. Mohammed Burma Hassan government since February 2003 over 8. Mohammed Issa Adam issues relating to discrimination and 9. Zakariya Abdel Mawla Abaker marginalisation. 10. Adam Mohammed Abu’l-Gasim 11. Adam Abdel Majid Mohammed The 168 men were then blindfolded and 12. Adam Adam Degaish (community taken in groups of about 40, on army leader) trucks to an area behind a hill near Deleij 13. Khalil Issa Tur village. They were then told to lie on the ground and shot by a force of about 45 People from Tairgo members of the military intelligence and 1. -

25 Prophets of Islam

Like 5.2k Search Qul . Home Prayer Times Ask Qul TV The Holy Qur'an Library Video Library Audio Library Islamic Occasions About Pearl of Wisdom Library » Our Messengers » 25 Prophets of Islam with regards to Allah's verse in the 25 Prophets of Islam Qur'an: "Indeed Allah desires to repel all impurity from you... 25 Prophets of Islam said,?'Impunity IS doubt, and by Allah, we never doubt in our Lord. How many prophets did God send to mankind? This is a debated issue, but what we know is what God has told us in the Quran. God says he sent a prophet to every nation. He says: Imam Ja'far ibn Muhammad al-Sadiq “For We assuredly sent amongst every People a Messenger, (with the command): ‘Serve God, and eschew Evil;’ of the people were [as] some whom God guided, and some on whom Error became inevitably (established). So travel through the earth, and see what was the Ibid. p. 200, no. 4 end of those who denied (the Truth)” (Quran 16:36) This is because one of the principles by which God operates is that He will never take a people to task unless He has made clear to them what His expectations are. Article Source The Quran mentions the names of 25 prophets and indicates there were others. It says: “Of some messengers We have already told you the story; of others We have not; - and to Moses God spoke direct.” (Quran 4:164) We acknowledge that 'Our Messengers Way' by 'Harun Yahya' for providing the The Names of the 25 Prophets Mentioned are as follows: original file containing the 'Our Adam Messengers'. -

Acts of Devotion

5 Acts of Devotion Recommended acts for every month of the Islamic year Sidi Idris b. Muhammad al-Iraqi Translation by Talut Dawd © 2018 Imam Ghazali Institute, USA No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, in- cluding photocopying, recording, and internet without prior permission of the Imam Ghazali Institute. Title: Acts of Devotion ISBN: 978-0-9984380-1-6 First Edition Author: Sidi Idris b. Muhammad al-Iraqi Translator: Talut Dawud Islamic Calligraphy: Courtesy of the Prince Ghazi Trust Senior Project Lead: Adnaan Sattaur Imam Ghazali Institute www.imamghazali.org / [email protected] Questions pertaining to the Imam Ghazali Institute may be directed to www.imamghazali.org or [email protected]. Dedicated to Shaykh Hassan Cisse We may not have met you in person, but your work, family, and impact has touched our lives. Contents Biography of the Shaykh ................................................... Preface ............................................................................... Author’s Introduction ..................................................... Acts of Devotion ................................................................ Section 1: Recommended Acts in the Month of Muharram ..................................................................... Section 2: Recommended Acts on the Last Wednesday of the Month of Safar ................................................... Section 3: The Remembrance of the Noble -

America, the Second ‘Ad: Prophecies About the D Ownfall of the United States 1

America, The Second ‘Ad: Prophecies about the D ownfall of the United States 1 David Cook 1. Introduction Predictions and prophecies about the United States of America appear quite frequently in modern Muslim apocalyp- tic literature.2 This literature forms a developing synthesis of classical traditions, Biblical exegesis— based largely on Protestant evangelical apocalyptic scenarios— and a pervasive anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. These three elements have been fused together to form a very powerful and relevant sce- nario which is capable of explaining events in the modern world to the satisfaction of the reader. The Muslim apocalyp- tist’s material previous to the modern period has stemmed in its entirety from the Prophet Muhammad and those of his generation to whom apocalypses are ascribed. Throughout the 1400 years of Muslim history, the accepted process has been to merely transmit this material from one generation to the next, without adding, deleting, or commenting on its signifi- cance to the generation in which a given author lives. There appears to be no interpretation of the relevance of a given tradition, nor any attempt to work the material into an apocalyptic “history,” in the sense of locating the predicted events among contemporary occurrences. For example, the David Cook, Assistant Professor Department of Religion Rice University, Houston, Texas, USA 150 America, the Second ‘Ad apocalyptic writer Muhammad b. ‘Ali al-Shawkani (d. 1834), who wrote a book on messianic expectations, does not men- tion any of the momentous events of his lifetime, which included the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, his home. There is not a shred of original material in the whole book, which runs to over 400 pages, and the “author” himself never speaks— rather it is wholly a compilation of earlier sources, and could just as easily have been compiled 1000 years previ- ously. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 20-639 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ________________________________ CALVARY CHAPEL DAYTON VALLEY, Petitioner, v. STEVE SISOLAK, GOVERNOR OF NEVADA, ET AL., Respondents. ________________________________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ________________________________ BRIEF AMICI CURIAE ISLAM AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM ACTION TEAM AND JEWISH COALITION FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ________________________________ HUNTON ANDREWS KURTH LLP ERICA N. PETERSON ELBERT LIN MICHAEL C. DINGMAN Counsel of Record 2200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW 951 East Byrd Street Washington, DC 20037 East Tower [email protected] Richmond, VA 23219 [email protected] [email protected] Phone: (202) 955-1500 Phone: (804) 788-8200 KATY BOATMAN 600 Travis, Suite 4200 Houston, Texas 77002 [email protected] Phone: (713) 220-4200 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTRODUCTION AND INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ................................................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 3 REASONS FOR GRANTING CERTIORARI ............ 4 I. This Court’s Review Is Necessary to Ensure Religious Freedom for Americans of All Faiths........................................................ 4 II. Nevada’s Directives Violate the Free Exercise Clause. ............................................... 16 A. Strict Scrutiny Analysis Applies to Nevada’s Directives. ............................... -

Mosques in the Seattle Area

* Children & Families Assistance Programs Mosques in the Puget Sound Area >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> Atlantic St. Family &Youth Center 206-329-2050 Emergency Resource Guide www.atlanticstreet.org Basic Food/ SNAP 1-877-501-2233 * AbuBakr Islamic Center 206-214-0200 Helping Muslims in Seattle Area Boys and Girls Club King County 206-436-1800 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> Boys and Girls Snohomish County 425-258-2436 * Bilal Islamic Com.Center 253-431-6022 Community Resources & Assistance Big Brothers and Sisters King /Pierce 206-763-9060 call 211 for Intake or assistance Snoh County 425-252-BBBS * Dar Al-Arqam 425-774-8852 www.win211.org CatholicCommunityServices206-328-5696/323-6336 This resource guide will assist you in searching Central Area Youth Association 206-322-6640 * Downtown Muslim Association information when seeking housing, medical, dental DSHS Child Support Division 1-800-526-8658 clinics, family aid, and general assistance. Everyone is Welcome BankonFinancial Advice/ Help * Everett Masjid *Be prepared in the event of a disaster! Family Works 206-694-6727 http://makeitthrough.org/ Friends of Youth Redmond 425-869-6490 * IECS- Ershad 425-243-4327 * Muslim Emergency Management FB Kent Youth & Family Services 253-859-0300 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> King County Aging /Disability Serv 206-684-0660 *Community Services Helplines Multi-Service Center Federal Way 253-838-6810 * Islamic Center Bothell 512-222-6996 Emergency Crisis call 911 Nexus 4 Youth & Families 253-939-2202 Information: -

181 the Mantle of Khidr1 Mystery, Myth and Meaning

ARAM, 20 (2008) 181-194. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.20.0.2033128S. HIRTENSTEIN 181 THE MANTLE OF KHIDR1 MYSTERY, MYTH AND MEANING ACCORDING TO MUHYIDDIN IBN ‘ARABI2 Mr. STEPHEN HIRTENSTEIN (Ibn ‘Arabi Society) INTRODUCTION At first sight there seems to be little connection between Elijah, George and Khidr, apart from the fact that in the Middle East they are frequently associ- ated with the same place by different religious traditions. Is it then a simple case of overlapping traditions, Jewish, Christian and Muslim, all of whom fo- cus on the Holy Land as part of their own heritage and take Abraham as their forefather? Certainly there is a view which suggests that Khidr is to Muslims what Elijah is to Jews, in respect of them both acting as initiator to the true believer, and which in itself is testimony to attempts to find common ground between the three traditions. The sacred sites associated with them over centu- ries seem to have accumulated worship in various forms, so that one sits quite literally on top of or next to another. The sites often exhibit similar attributes: for instance, the presence of water and greenness, suggesting fertility in a bar- ren land; or perhaps a cave, which represents a meeting-place of two worlds, the manifest and the hidden (and on occasion both elements are present, as at Banyas). Then there is the ancient theme of the spiritual side of man being dominant over the material, as suggested in the stories by the holy rider on a chariot or horse (or in the case of Khidr, a fish3). -

THEO-393 QB Spring 2015 Syllabus

! ! Course: THEO-393 Special Topics: The Qur’an and the Bible Semester: Spring 2015 Time: T R 11:00–12:15 Professor: Carlos A. Segovia Credits: 3 !Prerequisites: THEO-100 and one 200-level Theology course ! !1. Course objectives Notwithstanding its distinctively discontinuous style, the Qur’an repeatedly draws on the stock of Biblical stories and legends, which one often finds elliptically reworked in its pages. Occasionally, however, such reworked stories are better understood in light of their para-Bi- blical, both Jewish and Christian, glosses, on which the Qur’an relies as well, therefore. But what is the ultimate purpose of these complex intertextual strategies and how must they be approached and classified? Is it possible to speak of the Qur’an, at least partly, as an exegeti- cal work? And if so, what would this imply? Can the study of the Biblical and para-Biblical stories in the Qur’an, moreover, help to shed light on the development of the multilayered theological debate that took place in the 7th-century Near East? Lastly, which are the inter- textual connections susceptible of being established between prophecy, eschatology, and mes- sianology in the Qur’an – and how do they affect our understanding of Islam’s origins? All these questions ought to be examined afresh to understand the message of the Qur’an in its !inherent complexity and to implement interfaith dialogue. Students who successfully complete the course will have achieved the following learning ob- !jectives: • to understand the intertextual relations existing between the Qur’an and the Bible • to canvass the main results achieved in the contemporary study of Quranic intertextuality • to discern the message of the Qur’an in its inherent complexity and historical context • to critically asses the implications of the above-referred notions for modern interfaith dialo- gue !• to determine, by one’s own lights, how to better deal with all the aforementioned issues ! !2.