181 the Mantle of Khidr1 Mystery, Myth and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspectives Behind Translating House of Flesh by Yusuf Idris

C. Lindley Cross 12 June 2009 Perspectives Behind Translating House of Flesh by Yusuf Idris Within the canon of great minds and talents that brought Egypt to a literary renaissance between 1880 and 1960, Yusuf Idris (1927-1991) is widely acknowledged as the master of the Egyptian short story. Employing a compact, terse style, charged with an energy that viscerally engages the senses as much as it does the imagination and intellect, he burst into the public eye with a prolific outpouring of work in the years directly following the 1952 Revolution. His stories from the beginning were confrontational and provocative, articulated from his firm commitment to political activism. Although his literary efforts had largely petered out by the 1970s, the uncompromising zeal and intensity he brought to his short stories left a groundbreaking impression on the history of modern Arabic fiction. Inside the Arabic literary tradition, the short story (al-qiṣṣah al-qaṣīrah, or al-uqṣuṣah) is in itself a genre that bears a political dimension, first and foremost due to its having been largely inspired by foreign models.1 Even in Europe and North America, it only achieved widespread acceptance as a literary form distinct from novels in the early nineteenth century. In the climate of French literary prestige and British colonialism encroaching upon Egypt’s identity, the choice whether to adopt or reject such forms was often indicative of a wider political view. Some intellectuals were convinced that the only way to save Egypt from cultural effacement was to re-appropriate the language and forms of the great classical masters like Abu Nawas and al- Mutanabbi and inject them into contemporary literature, warding off further corruption as a vaccine wards off disease. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam

Institute of Asian and African Studies at The Hebrew University The Max Schloessinger Memorial Foundation REPRINT FROM JERUSALEM STUDIES IN ARABIC AND ISLAM I 1979 THE MAGNES PRESS. THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY. JERUSALEM PROPHETS AND PROGENITORS IN THE EARLY SHI'ATRADITION* Uri Rubin INTRODUCTION As is well known, the Shi 'I belief that 'Ali' should have been Muhammad's succes- sor was based on the principle of hereditary Califate, or rather Imamate. 'Ali's father, Abu Talib, and Muhammad's father, 'Abdallah, were brothers, so that Muhammad and 'Ali were first cousins. Since the Prophet himself left no sons, the Shi 'a regarded' All as his only rightful successor.' Several Shi 'I traditions proclaim 'All's family relationship (qariiba) to Muhammad as the basis for his hereditary rights. For the sake of brevity we shall only point out some of the earliest.A number of these early Shi T traditions center around the "brothering", i.e. the mu'akhiih which took place after the hijra; this was an agreement by which each emigrant was paired with one of the Ansar and the two, who thus became brothers, were supposed to inherit each other (see Qur'an, IV, 33? 'All, as an exception, was paired not with one of the Ansar but with the Prophet himself." A certain verse in the Qur'an (VIII, 72) was interpreted as stating that the practice of mu iikhiin was confined only to the Muhajinin and the Ansar, to the exclusion of those believers who had stayed back in Mecca after the hijra. They re- tained the old practice of inheritance according to blood-relationship." This prac- tice, which was introduced in al-Madi na, affected the hereditary rights of the families of the Muhajiriin who were supposed to leave their legacy to their Ansari * This article is a revised form of a chapter from my thesis on some aspects of Muhammad's prophethood in the early literature of hadt th. -

The Differences Between Sunni and Shia Muslims the Words Sunni and Shia Appear Regularly in Stories About the Muslim World but Few People Know What They Really Mean

Name_____________________________ Period_______ Date___________ The Differences Between Sunni and Shia Muslims The words Sunni and Shia appear regularly in stories about the Muslim world but few people know what they really mean. Religion is important in Muslim countries and understanding Sunni and Shia beliefs is important in understanding the modern Muslim world. The beginnings The division between the Sunnis and the Shia is the largest and oldest in the history of Islam. To under- stand it, it is good to know a little bit about the political legacy of the Prophet Muhammad. When the Prophet died in the early 7th Century he not only left the religion of Islam but also an Islamic State in the Arabian Peninsula with around one hundred thousand Muslim inhabitants. It was the ques- tion of who should succeed the Prophet and lead the new Islamic state that created the divide. One group of Muslims (the larger group) elected Abu Bakr, a close companion of the Prophet as the next caliph (leader) of the Muslims and he was then appointed. However, a smaller group believed that the Prophet's son-in-law, Ali, should become the caliph. Muslims who believe that Abu Bakr should be the next leader have come to be known as Sunni. Muslims who believe Ali should have been the next leader are now known as Shia. The use of the word successor should not be confused to mean that that those that followed the Prophet Muhammad were also prophets - both Shia and Sunni agree that Muhammad was the final prophet. How do Sunni and Shia differ on beliefs? Initially, the difference between Sunni and Shia was merely a difference concerning who should lead the Muslim community. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

Qisas Contribution to the Theory of Ghaybah in Twelver Shı

− QisasAA Contribution to the Theory of Ghaybah in Twelver Shı‘ism QisasAA Contribution to the Theory of Ghaybah in Twelver Shı‘ism− Kyoko YOSHIDA* In this paper, I analyze the role of qisasAA (narrative stories) materials, which are often incorporated into the Twelver Shı‘ite− theological discussions, by focusing mainly on the stories of the al-KhidrA (or al- Khadir)A legend in the tenth and the eleventh century ghaybah discussions. The goal is to demonstrate the essential function that the narrative elements have performed in argumentations of the Twelver Shı‘ite− theory of Imam. The importance of qisasAA materials in promulgating the doctrine of Imamah− in the Twelver Shı‘ism− tended to be underestimated in the previous studies because of the mythical and legendary representations of qisasAA materials. My analysis makes clear that qisasAA materials do not only illustrate events in the sacred history, but also open possibilities for the miraculous affairs to happen in the actual world. In this sense, qisasAA materials have been utilized as a useful element for the doctrinal argumentations in the Twelver Shı‘ism.− − Keywords: stories, al-Khidr,A occultation, Ibn Babawayh, longevity Introduction In this paper, I analyze how qisasAA traditions have been utilized in the promulgation of Twelver Shı‘ite− doctrine. The term qisasAA (sing. qissah AA ) means narrative stories addressed in the Qur’an− principally. However, it also includes the orated and elaborated tales and legends based on storytelling that flourished in the early Umayyad era (Norris 1983, 247). Their contents vary: archaic traditions spread in the pre-Islamic Arab world, patriarchal stories from Biblical and Jewish sources, and Islamized sayings and maxims of the sages and the ascetics of the day.1 In spite of a variety of the different sources and origins, Muslim faith has accepted these stories as long as they could support and advocate the Qur’anic− *Specially Appointed Researcher of Global COE Program “Development and Systematization of Death and Life Studies,” University of Tokyo Vol. -

TITLE of UNIT What Do Muslims Do at the Mosque

Sandwell SACRE RE Support Materials 2018 Unit 1.8 Beginning to learn about Islam. Muslims and Mosques in Sandwell Year 1 or 2 Sandwell SACRE Support for RE Beginning to learn from Islam : Mosques in Sandwell 1 Sandwell SACRE RE Support Materials 2018 Beginning to Learn about Islam: What can we find out? YEAR GROUP 1 or 2 ABOUT THIS UNIT: Islam is a major religion in Sandwell, the UK and globally. It is a requirement of the Sandwell RE syllabus that pupils learn about Islam throughout their primary school years, as well as about Christianity and other religions. This unit might form part of a wider curriculum theme on the local environment, or special places, or ‘where we live together’. It is very valuable for children to experience a school trip to a mosque, or another sacred building. But there is also much value in the virtual and pictorial encounter with a mosque that teachers can provide. This unit looks simply at Mosques and worship in Muslim life and in celebrations and festivals. Local connections are important too. Estimated time for this unit: 6 short sessions and 1 longer session if a visit to a mosque takes place. Where this unit fits in: Through this unit of work many children who are not Muslims will do some of their first learning about the Islamic faith. They should learn that it is a local religion in Sandwell and matters to people they live near to. Other children who are Muslims may find learning from their own religion is affirming of their identity, and opens up channels between home and school that hep them to learn. -

Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011

Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 Colorado Northwestern Community College Literature and the Arts of Northwest Colorado Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 EDITOR ART EDITOR PRODUCTION/DESIGN Joe Wiley Elizabeth Robinson Denise Wade EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Ally Palmer Jinnah Schrock Rose Peterson Mary Slack Ariel Sanchez Michael Willie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The staff of Waving Hands Review thanks the following people: -CNCC President Russell George, his cabinet, the RJCD Board of Trustees, the MCAJCD Board of Control, and the CNCC Marketing Department for continued funding and support -All those who submitted work -All those who encouraged submissions Waving Hands Review, the literature and arts magazine of Colorado Northwestern Community College, seeks to publish exemplary works by emerging and established writers and artists of Northwest Colorado. Submissions in poetry, fiction, non-fiction, drama, photography, and art remain anonymous until a quality-based selection is made. Unsolicited submissions are welcome between September 1 and March 1. We accept online submissions only. Please visit the Waving Hands Review website at www.cncc.edu/waving_hands/ for detailed submission guidelines, or go to the CNCC homepage and click on the Waving Hands Review logo. Waving Hands Review is staffed by students of Creative Writing II. All works Copyright 2011 by individual authors and artists. Volume 3, Issue 3, 2011 Table of Contents Artwork Yuri Chicovsky Cover Self-Portrait Janele Husband 17 Blanketed Deer Peter Bergmann 18 Winter -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

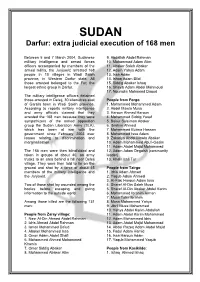

Darfur: Extra Judicial Execution of 168 Men

SUDAN Darfur: extra judicial execution of 168 men Between 5 and 7 March 2004, Sudanese 9. Abdallah Abdel Rahman military intelligence and armed forces 10. Mohammed Adam Atim officers accompanied by members of the 11. Abaker Saleh Abaker armed militia, the Janjawid, arrested 168 12. Adam Yahya Adam people in 10 villages in Wadi Saleh 13. Issa Adam province, in Western Darfur state. All 14. Ishaq Adam Bilal those arrested belonged to the Fur, the 15. Siddig Abaker Ishaq largest ethnic group in Darfur. 16. Shayib Adam Abdel Mahmoud 17. Nouradin Mohamed Daoud The military intelligence officers detained those arrested in Deleij, 30 kilometres east People from Forgo of Garsila town in Wadi Saleh province. 1. Mohammed Mohammed Adam According to reports military intelligence 2. Abdel Mawla Musa and army officials claimed that they 3. Haroun Ahmed Haroun arrested the 168 men because they were 4. Mohammed Siddig Yusuf sympathizers of the armed opposition 5. Bakur Suleiman Abaker group the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), 6. Ibrahim Ahmed which has been at war with the 7. Mohammed Burma Hassan government since February 2003 over 8. Mohammed Issa Adam issues relating to discrimination and 9. Zakariya Abdel Mawla Abaker marginalisation. 10. Adam Mohammed Abu’l-Gasim 11. Adam Abdel Majid Mohammed The 168 men were then blindfolded and 12. Adam Adam Degaish (community taken in groups of about 40, on army leader) trucks to an area behind a hill near Deleij 13. Khalil Issa Tur village. They were then told to lie on the ground and shot by a force of about 45 People from Tairgo members of the military intelligence and 1.