The Security and Political Impacts of Disbanding the Iraqi Armed Forces After 2003-War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran Vies for More Influence in Iraq at a Budget Price by Farzin Nadimi

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3405 Iran Vies for More Influence in Iraq at a Budget Price by Farzin Nadimi Dec 3, 2020 Also available in Arabic / Farsi ABOUT THE AUTHORS Farzin Nadimi Farzin Nadimi, an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, is a Washington-based analyst specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Persian Gulf region. Brief Analysis Tehran aims to earn hard currency for its relatively cheap military hardware, ideally boosting its leverage in Baghdad at a fraction of the cost that the United States has been spending there. n November 14, a large Iraqi defense delegation began a four-day visit to Tehran as a follow-up to previous O exchanges with Iranian officials. The trip was led by Sunni defense minister Juma Saadoun al-Jubouri and included the commanders of each Iraqi military branch. According to Jubouri, its main goal was to “deepen” bilateral military and security cooperation. Three days later, the commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF), Brig. Gen. Esmail Qaani, reportedly paid a secret visit to Baghdad. These exchanges are all the more notable because they came after the UN ban on arms deals with Iran expired in October. Tehran is now free to market and sell its weapons abroad, and several potential customers have already shown interest—not just Iraq, but also Syria, Venezuela, and other players. To be sure, all of these governments are financially constrained, and the United States will likely continue disrupting such deals via existing secondary sanctions, most of them based on UN Security Council resolutions adopted between 2006 and 2015. -

One Hundred Eighth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 3289 One Hundred Eighth Congress of the United States of America AT THE FIRST SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Tuesday, the seventh day of January, two thousand and three An Act Making emergency supplemental appropriations for defense and for the reconstruc- tion of Iraq and Afghanistan for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2004, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the following sums are appropriated, out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2004, and for other purposes, namely: TITLE I—NATIONAL SECURITY CHAPTER 1 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE—MILITARY MILITARY PERSONNEL MILITARY PERSONNEL, ARMY For an additional amount for ‘‘Military Personnel, Army’’, $12,858,870,000. MILITARY PERSONNEL, NAVY For an additional amount for ‘‘Military Personnel, Navy’’, $816,100,000. MILITARY PERSONNEL, MARINE CORPS For an additional amount for ‘‘Military Personnel, Marine Corps’’, $753,190,000. MILITARY PERSONNEL, AIR FORCE For an additional amount for ‘‘Military Personnel, Air Force’’, $3,384,700,000. OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE, ARMY For an additional amount for ‘‘Operation and Maintenance, Army’’, $23,997,064,000. H. R. 3289—2 OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE, NAVY (INCLUDING TRANSFER OF FUNDS) For an additional amount for ‘‘Operation and Maintenance, Navy’’, $1,956,258,000, of which up to $80,000,000 may be trans- ferred to the Department of Homeland Security for Coast Guard Operations. OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE, MARINE CORPS For an additional amount for ‘‘Operation and Maintenance, Marine Corps’’, $1,198,981,000. -

How Soon Is Safe?

HOW SOON IS SAFE? IRAQI FORCE DEVELOPMENT AND ―CONDITIONS-BASED‖ US WITHDRAWALS Final Review Draft: February 5, 2009 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy And Adam Mausner [email protected] [email protected] Cordesman: Iraqi Forces and US Withdrawals 4/22/09 Page ii The Authors would like to thank the men and women of the Multinational Force–Iraq and Multinational Security Transition Command - Iraq for their generous contribution to our work. The Authors would also like to thank David Kasten for his research assistance. Cordesman: Iraqi Forces and US Withdrawals 4/22/09 Page iii Executive Summary The US and Iraq now face a transition period that may well be as challenging as defeating Al Qa‘ida in Iraq, the other elements of the insurgency, and the threat from militias like the Mahdi Army. Iraq has made progress in political accommodation and in improving security. No one, however, can yet be certain that Iraq will achieve a enough political accommodation to deal with its remaining internal problems, whether there will be a new surge of civil violence, or whether Iraq will face problems with its neighbors. Iran seeks to expand its influence, and Turkey will not tolerate a sanctuary for hostile Kurdish movements like the PKK. Arab support for Iraq remains weak, and Iraq‘s Arab neighbors fear both Shi‘ite and Iranian dominance of Iraq as well as a ―Shi‘ite crescent‖ that includes Syria and Lebanon.. Much will depend on the capabilities of Iraqi security forces (ISF) and their ability to deal with internal conflicts and external pressures. -

Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected]

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Matuschak, Jennie, "Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War" (2019). Honors Theses. 486. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/486 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments My first thanks is to my advisor, Mehmet Döşemeci. Without taking your class my freshman year, I probably would not have become a history major, which has changed my outlook on the world. Time will tell whether this is good or bad, but for now I am appreciative of your guidance. Also, thank you to my second advisor, Beeta Baghoolizadeh, who dealt with draft after draft and provided my thesis with the critiques it needed to stand strongly on its own. Thank you to my friends for your support and loyalty over the past four years, which have pushed me to become the best version of myself. Most importantly, I value the distractions when I needed a break from hanging out with Saddam. Special shout-out to Andrew Raisner for painstakingly reading and editing everything I’ve written, starting from my proposal all the way to the final piece. -

A Tale of Two Cities the Use of Explosive Weapons in Basra and Fallujah, Iraq, 2003-4 Report by Jenna Corderoy and Robert Perkins

December 2014 A TALE OF TWO CITIES The use of explosive weapons in Basra and Fallujah, Iraq, 2003-4 Report by Jenna Corderoy and Robert Perkins Editor Iain Overton With thanks to Henry Dodd, Jane Hunter, Steve Smith and Iraq Body Count Copyright © Action on Armed Violence (December 2014) Cover Illustration A US Marine Corps M1A1 Abrams tank fires its main gun into a building in Fallujah during Operation Al Fajr/Phantom Fury, 10 December 2004, Lance Corporal James J. Vooris (UMSC) Infographic Sarah Leo Design and Printing Matt Bellamy Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome Research and publications funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A tale of two cities | 1 CONTENTS FOREWORD 2 IRAQ: A TIMELINE 3 INTRODUCTION: IRAQ AND EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS 4 INTERnatiONAL HumanitaRIAN LAW 6 AND RulES OF ENGAGEMENT BASRA, 2003 8 Rattling the Cage 8 Air strikes: Munition selection 11 FALLUJAH, 2004 14 Firepower for manpower 14 Counting the cost 17 THE AFTERmath AND LESSONS LEARNED 20 CONCLUSION 22 RECOMMENDatiONS 23 2 | Action on Armed Violence FOREWORD Sound military tactics employed in the pursuit of strategic objectives tend to restrict the use of explosive force in populated areas “ [... There are] ample examples from other international military operations that indicate that the excessive use of explosive force in populated areas can undermine both tactical and strategic objectives.” Bård Glad Pedersen, State Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, 17 June 20141 The language of conflict has changed enormously. their government is not the governing authority. Today engagements are often fought and justified Three case studies in three places most heavily- through a public mandate to protect civilians. -

Iraq: U.S. Military Operations

Order Code RL31701 Iraq: U.S. Military Operations Updated July 15, 2007 Steve Bowman Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Iraq: U.S. Military Operations Summary Iraq’s chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons programs, together with Iraqi long-range missile development and support for Al Qaeda terrorism, were the primary justifications put forward for military action. On March 17, 2003, President Bush issued an ultimatum demanding that Saddam Hussein and his sons depart from Iraq within 48 hours. On March 19, offensive operations began with air strikes against Iraqi leadership positions. By April 15, after 27 days of operations, coalition forces were in relative control of all major Iraqi cities and Iraqi political and military leadership had disintegrated. On May 1, 2003, President Bush declared an end to major combat operations. There was no use of chemical or biological (CB) weapons, and no CB or nuclear weapons stockpiles or production facilities have been found. The major challenges to coalition forces are now quelling a persistent Iraqi resistance movement and training/retaining sufficient Iraqi security forces to assume responsibility for the nations domestic security. Though initially denying that there was an organized resistance movement, DOD officials have now acknowledged there is regional/local organization, with apparently ample supplies of arms and funding. CENTCOM has characterized the Iraqi resistance as “a classical guerrilla-type campaign.” DOD initially believed the resistance to consist primarily of former regime supporters and foreign fighters; however, it has now acknowledged that growing resentment of coalition forces and an increase in sectarian conflicts, independent of connections with the earlier regime, are contributing to the insurgency. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Fighting-For-Kurdistan.Pdf

Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq CRU Report Feike Fliervoet Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq Feike Fliervoet CRU Report March 2018 March 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Peshmerga, Kurdish Army © Flickr / Kurdishstruggle Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Feike Fliervoet is a Visiting Research Fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit where she contributes to the Levant research programme, a three year long project that seeks to identify the origins and functions of hybrid security arrangements and their influence on state performance and development. -

The Real Outcome of the Iraq War: US and Iranian Strategic Competition in Iraq

The Real Outcome of the Iraq War: US and Iranian Strategic Competition in Iraq By Anthony H. Cordesman, Peter Alsis, Adam Mausner, and Charles Loi Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy Revised: December 20, 2011 Note: This draft is being circulated for comments and suggestions. Please provide them to [email protected] Chapter 6: US Strategic Competition with Iran: Competition in Iraq 2 Executive Summary "Americans planted a tree in Iraq. They watered that tree, pruned it, and cared for it. Ask your American friends why they're leaving now before the tree bears fruit." --Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.1 Iraq has become a key focus of the strategic competition between the United States and Iran. The history of this competition has been shaped by the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), the 1991 Gulf War, and the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Since the 2003 war, both the US and Iran have competed to shape the structure of Post-Saddam Iraq’s politics, governance, economics, and security. The US has gone to great lengths to counter Iranian influence in Iraq, including using its status as an occupying power and Iraq’s main source of aid, as well as through information operations and more traditional press statements highlighting Iranian meddling. However, containing Iranian influence, while important, is not America’s main goal in Iraq. It is rather to create a stable democratic Iraq that can defeat the remaining extremist and insurgent elements, defend against foreign threats, sustain an able civil society, and emerge as a stable power friendly to the US and its Gulf allies. -

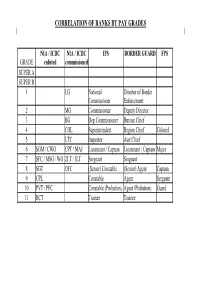

Security Salary Matrix (.Pdf)

CORRELATION OF RANKS BY PAY GRADES NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER GUARDFPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B 1 LG National Director of Border Commissioner Enforcement 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 3 BG Dep Commissioner Bureau Chief 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 6 SGM / CWO CPT / MAJ Lieutenant / Captain Lieutenant / Captain Major 7 SFC / MSG / WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 8 SGT OFC (Senior) Constable (Senior) Agent Captain 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 11 RCT Trainee Trainee COMPARISON OF RANKS (SHOWING INITIAL STEP INCREMENT) NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER FPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B National Dir of Border 1 LG Commissioner Enforcement 1 1 1 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 1 1 1 Dep 3 BG Commissioner Bureau Chief 1 1 1 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 1 1 1 1 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 1 1 1 6 SGM / CWO CAPT/MAJ Lieut / Captain Lieut / Captain Major 1 2 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 7 SFC/MSG/WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 4 7 8 6 7 6 6 8 SGT OFC (Snr) Constable (Snr) Agent Captain 6 8 6 6 1 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 7 5 5 1 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 4 8 4 4 1 11 Recruit Trainee Trainee 1 4 4 ENTRY LEVEL SALARIES FOR NEW IRAQI ARMY / IRAQI CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS STEPS- SALARIES LISTED IN NEW IRAQI DINAR Grade Enlisted Commission 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 LG 740,000 760,000 780,000 80,0000 820,000 840,000 860,000 880,000 2 MG 574,000 589,000 605,000 620,000 636,000 651,000 -

The Outcome of Invasion: US and Iranian Strategic Competition in Iraq

a report of the csis burke chair in strategy The Outcome of Invasion: US and Iranian Strategic Competition in Iraq Authors Adam Mausner Sam Khazai Anthony H. Cordesman Peter Alsis Charles Loi March 2012 Chapter VII: US Strategic Competition with Iran: Competition in Iraq 16/3/12 2 Executive Summary "Americans planted a tree in Iraq. They watered that tree, pruned it, and cared for it. Ask your American friends why they're leaving now before the tree bears fruit." --Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.1 Iraq has become a key focus of the strategic competition between the United States and Iran. The history of this competition has been shaped by the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), the 1991 Gulf War, the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, and now by the withdrawal of US military forces. It is a competition increasingly shaped by Iraq’s turbulent domestic politics and power struggles, and where both the US and Iran compete to shape the structure of Iraq’s future politics, governance, economics, and security. An Uncertain Level of US Influence The US has gone to great lengths to counter Iranian influence in Iraq, including using its status as an occupying power and Iraq’s main source of aid, as well as through information operations and more traditional press statements highlighting Iranian meddling. However, containing Iranian influence, while important, is not America’s main goal in Iraq. It is rather to create a stable democratic Iraq that can defeat the remaining extremist and insurgent elements, defend against foreign threats, sustain an able civil society, and emerge as a stable power friendly to the US and its Gulf allies. -

MIDDLE EAST WATCH OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments The

MIDDLE EAST WATCH OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments The political earthquake that shook the Middle East on September 13, when Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) signed an interim self-government accord, may have marked the beginning of the end of the forty-five-year-old Arab-Israeli conflict. In the medium term, it may also come to mark a parallel improvement in human rights conditionsCnot just in the Israeli-occupied territories, but in those frontline states that have long used the conflict as a pretext for violations of the fundamental rights of their own peoples. Such aspirations could, equally, prove to be mere wishful thinking: human rights per se figured little in the interstate negotiations that took place during 1993, and few officials from any party to the talks, including the United States, publicly articulated concern for human rights. Under prodding, PLO Chairman Yassir Arafat was one of those who did, after the signing; but, misgivings persisted as to whether the PLO was truly committed to a future in which respect for human rights and a pluralistic democracy would be realized. In counterpoint, there were no early signs of an Israeli reassessment of long-established abusive policies and practices in the occupied territories. Welcome though the Israel-PLO agreement was as an augury of peace, in the region as a wholeCfrom the Maghreb states of North Africa to IranCthe accord was overshadowed by a broader conflict with pervasive implications for human rights: a contest for power, ideological domination, and control over social behavior between insurgent Islamists and established regimes, themselves often of little popular legitimacy and a secular, pro-Western cast.