Survival of the Bankruptcy Cooperation Statute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Convention on Bankruptcy, Winding-Up, Arrangements, Com

Bulletin of the European Communities Supplement 2/82 Draft Convention on bankruptcy, winding-up, arrangements, com positions and similar proceedings Report on the draft Convention on bankruptcy, winding-up, arrange ments, compositions and similar pro ceedings EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Commission The draft Convention on bankruptcy, winding-up, arrangements, compositions and similar proceedings was drawn up in pursuance of Article 220 of the Treaty establish ing the European Economic Community, under which the Member States were to 'enter into negotiations with each other with a view to securing for the benefit of their nationals ... the simplification of formalities governing the reciprocal recogni tion and enforcement of judgments of courts or tribunals ... '. The need for negotiations on these matters had been clear to the Member States from the Community's inception. The negotiations culminated in the Convention on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters, which was signed in Brussels on 27 September 1968 and has since been amended by the Convention on the accession of the new Member States to the Convention, signed in Luxembourg on 9 October 1978.1 However, bankruptcies, compositions and other analogous proceedings were excluded from the scope of the Judgments Convention. As early as 1960 it had been decided, because of the special problems involved, to negotiate a special convention concerning such proceedings, and a paral lel working party had been set up under Commission auspices, composed of govern ment and Commission experts together with observers from the Benelux Commis sion for the study of the unification of law and the Hague Conference on Private International Law. -

Bankruptcy and Diligence Etc. (Scotland) Act 2007 (Asp 3)

Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Act 2007 (asp 3) Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Act 2007 2007 asp 3 CONTENTS Section PART 1 BANKRUPTCY Duration of bankruptcy 1 Discharge of debtor Bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings 2 Bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings Effect of bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings 3 Disqualification from being appointed as receiver 4 Disqualification for nomination, election and holding office as member of local authority 5 Orders relating to disqualification The trustee in the sequestration 6 Amalgamation of offices of interim trustee and permanent trustee 7 Repeal of trustee’s residence requirement 8 Duties of trustee 9 Grounds for resignation or removal of trustee 10 Termination of interim trustee’s functions 11 Statutory meeting and election of trustee 12 Replacement of trustee acting in more than one sequestration 13 Requirement to hold money in interest bearing account Debtor applications 14 Debtor applications 15 Debtor applications by low income, low asset debtors Jurisdiction 16 Sequestration proceedings to be competent only before sheriff ii Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Act 2007 (asp 3) Vesting of estate and dealings of debtor 17 Vesting of estate and dealings of debtor Income received by debtor after sequestration 18 Income received by debtor after sequestration Debtor’s home and other heritable property 19 Debtor’s home and other heritable property Protected trust deeds 20 Modification of provisions relating to protected trust deeds Modification -

Fines and Recoveries Act 1833

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Fines and Recoveries Act 1833. (See end of Document for details) Fines and Recoveries Act 1833 1833 CHAPTER 74 3 and 4 Will 4 An Act for the abolition of fines and recoveries, and for the substitution of more simple modes of assurance. [28th August 1833] Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Short title “The Fines and Recoveries Act, 1833” given by short Titles Act 1896 (c. 14) C2 Words of enactment and certain other words repealed by Statute Law Revision (No.2) Act 1888 (c. 57), Statute Law Revision Act 1890 (c. 33) and Statute Law Revision Act 1892 (c. 19) C3 This Act is not necessarily in the form in which it has effect in Northern Ireland Commencement Information I1 Act wholly in force at Royal Assent [1.] Meaning of certain words and expressions. Estate. Lands. Base fee. Estate tail. Actual tenant in tail. Tenant in tail. Tenant in tail entitled to a base fee. Money. Person. Number and gender. Settlement. In the construction of this Act the word “Lands”shall extend to manors, advowsons, rectories, messuages, lands, tenements, tithes, rents, and hereditaments of any tenure (except copy of court roll), and whether corporeal or incorporeal [F1, and any undivided share thereof], but when accompanied by some expression including or denoting the tenure by copy of court roll, shall extend to manors, messuages, lands, tenements, and hereditaments of that tenure [F1, and any undivided share thereof]; and the word “estate”shall extend to an estate in equity -

Bankruptcy (Scotland) Act 1985 CHAPTER 66

Bankruptcy (Scotland) Act 1985 CHAPTER 66 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Administration of bankruptcy Section 1. Accountant in Bankruptcy. 2. Interim trustee. 3. Permanent trustee. 4. Commissioners. Petitions for sequestration 5. Sequestration of the estate of living or deceased debtor. 6. Sequestration of other estates. 7. Meaning of apparent insolvency. 8. Further provisions relating to presentation of petitions. 9. Jurisdiction. 10. Concurrent proceedings for sequestration or analogous remedy. 11. Creditor's oath. Award of sequestration and appointment and resignation of interim trustee 12. When sequestration is awarded. 13. Appointment and resignation of interim trustee. 14. Registration of court order. 15. Further provisions relating to award of sequestration. 16. Petitions for recall of sequestration. 17. Recall of sequestration. Period between award of sequestration and statutory meeting of creditors 18. Interim preservation of estate. 19. Debtor's list of assets and liabilities. 20. Trustee's duties on receipt of list of assets and liabilities. A ii c. 66 ° Bankruptcy (Scotland) Act 1985 Statutory meeting of creditors and confirmation of permanent trustee Section 21. Calling of statutory meeting. 22. Submission of claims for voting purposes at statutory meeting. 23. Proceedings at statutory meeting before election of permanent trustee. 24. Election of permanent trustee. 25. Confirmation of permanent trustee. 26. Provisions relating to termination of interim trustee's functions. 27. Discharge of interim trustee. Replacement ofpermanent trustee 28. Resignation and death of permanent trustee. 29. Removal of permanent trustee and trustee not acting. Election, resignation and removal of commissioners 30. Election, resignation and removal. of commissioners. Vesting of estate in permanent trustee 31. Vesting of estate at date of sequestration. -

Statute Law Revision Bill 2007 ————————

———————— AN BILLE UM ATHCHO´ IRIU´ AN DLI´ REACHTU´ IL 2007 STATUTE LAW REVISION BILL 2007 ———————— Mar a tionscnaı´odh As initiated ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 [No. 5 of 2007] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas., 1. c. 3 General Pier and Harbour Act 1861 Amendment Act 1862 25 & 26 Vict., c. -

![Bankruptcy and Diligence Etc. (Scotland) Bill [AS AMENDED at STAGE 2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5631/bankruptcy-and-diligence-etc-scotland-bill-as-amended-at-stage-2-785631.webp)

Bankruptcy and Diligence Etc. (Scotland) Bill [AS AMENDED at STAGE 2]

Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Bill [AS AMENDED AT STAGE 2] CONTENTS Section PART 1 BANKRUPTCY Duration of bankruptcy 1 Discharge of debtor Bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings 2 Bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertaking s Effect of bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings 3 Disqualification from being appointed as receiver 4 Disqualification for nomination, election and holding office as member of local authority 5 Orders relating to disqualification The trustee in the sequestration 6 Amalgamation of offices of interim trustee and permanent trustee 7 Repeal of trustee’s residence requirement 8 Duties of trustee 9 Grounds for resignation or removal of trustee 10 Termination of interim trustee’s functions 11 Statuto ry meeting and election of trustee 12 Replacement of trustee acting in more than one sequestration 13 Requirement to hold money in interest bearing account Debtor applications 14 Debtor applications 14A Debtor applications by low income, low asset debtors Jurisdiction 15 Sequestration proceedings to be competent only before sheriff Income received by debtor after sequestration 16 Income received by debtor after sequestration Debtor’s home and other heritable property 17 Debtor’s home and other heritable property SP Bill 50A Session 2 ( 2006 ) ii Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Bill Protected trust deeds 18 Modification of provisions relating to protected trust deeds Modification of composition procedure 19 Modification of composition procedure Status and powers of Accountant in Bankruptcy -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

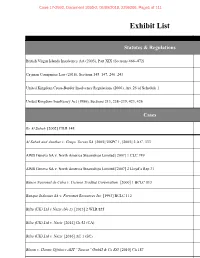

Exhibit List

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L. -

———————— Number 28 of 2007 ———————— STATUTE LAW REVISION ACT 2007 ———————— ARRAN

Click here for Explanatory Memorandum ———————— Number 28 of 2007 ———————— STATUTE LAW REVISION ACT 2007 ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 1 [No. 28.]Statute Law Revision Act 2007. [2007.] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 [2007.]Statute Law Revision Act 2007. [No. 28.] Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, sess. 2, c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished. -

Scotland) Act 2007

Bankruptcy and Diligence etc. (Scotland) Act 2007 2007 asp 3 CONTENTS PART 1 BANKRUPTCY Duration of bankruptcy Section 1 Discharge of debtor Bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings 2 Bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings Effect of bankruptcy restrictions orders and undertakings 3 Disqualification from being appointed as receiver 4 Disqualification for nomination, election and holding office as member of local authority 5 Orders relating to disqualification The trustee in the sequestration 6 Amalgamation of offices of interim trustee and permanent trustee 7 Repeal of trustee's residence requirement 8 Duties of trustee 9 Grounds for resignation or removal of trustee 10 Termination of interim trustee's functions 11 Statutory meeting and election of trustee 12 Replacement of trustee acting in more than one sequestration 13 Requirement to hold money in interest bearing account Debtor applications 14 Debtor applications 15 Debtor applications by low income, low asset debtors Jurisdiction 16 Sequestration proceedings to be competent only before sheriff Vesting of estate and dealings of debtor 17 Vesting of estate and dealings of debtor Income received by debtor after sequestration 18 Income received by debtor after sequestration Debtor's home and other heritable property 19 Debtor's home and other heritable property Protected trust deeds 20 Modification of provisions relating to protected trust deeds Modification of composition procedure 21 Modification of composition procedure Status and powers of Accountant in Bankruptcy -

The Law of Suretyship and Indemnity in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES The law of suretyship and indemnity in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland COMPETITION - APPROXIMATION OF LEGISLATION SERIES - 1976 - 28 I This study has been made in order to bring together the basic information necessary for the drafting of a Directive harmonizing the law of Suretyship in the Community. It deals with suretyship and other personal guarantees governed by the laws of England and Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Ireland. It includes a description of the types of suretyship covered and sets out the main similarities and differences which exist as between the various types in these countries. It supplements the study which was published in 1971 (Competition Series, No 14) dealing with suretyship in the laws of the founder Members of the Community. COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES The law of suretyship and indemnity in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland TREVOR C. HARTLEY Lecturer in Law in The London School of Economics and Political Science STUDIES Competition — Approximation of legislation Series No 28 Brussels, March 1974 Manuscript completed in March 1974 Copyright ECSC/EEC/EAEC, Brussels and Luxembourg, 1976 Printed in Luxembourg Part I SURETYSHIP AND INDEMNITY IN BRITISH AND IRISH LAW Chapter 1 SURETYSHIP AND INDEMNITY : BASIC CONCEPTS Introduction Territories covered - This study covers the following territories : 1. England and Wales (England and Wales form a single legal unit; therefore when there is a reference to "England" it may be assumed that what is said applies to Wales as well). 2. Scotland.