BS Mardhekar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUJARATI PAPER I Section A

GUJARATI PAPER I Section A (1) History of Gujarati Language with special reference to New Indo-Aryan i.e. last one thousand years. (2) Significant features of the Gujarati language : phonology, morphology and syntax. (3) Major dialects : Surti, pattani, charotari and Saurashtri. History of Gujarati literature Medieval : 4. Jaina tradition 5. Bhakti tradition : Sagun and Nirgun (Jnanmargi) 6. Non-sectarian tradition (Laukik parampara) Modern : 7. Sudharak yug 8. Pandit yug 9. Gandhi yug 10. Anu-Gandhi yug 11. Adhunik yug Section B Literary Forms : (Salient features, history and development of the following literary forms :) (a) Medieval 1. Narratives : Rasa, Akhyan and Padyavarta 2. Lyrical: Pada (b) Folk 3. Bhavai (c) Modern 4. Fiction : Novel and Short Story 5. Drama 6. Literary Essay 7. Lyrical Poetry (d) Criticism 8. History of theoretical Gujarati criticism 9. Recent research in folk tradition. PAPER II (Answers must be written in Gujarati) The paper will require first-hand reading of the texts prescribed and will be designed to test the critical ability of the candidate. Section A 1. Medieval (i) Vasantvilas phagu—AJNATKRUT (ii) Kadambari—BHALAN (iii) Sudamacharitra—PREMANAND (iv) Chandrachandravatini varta—SHAMAL (v) Akhegeeta—AKHO 2. Sudharakyug & Pandityug (vi) Mari Hakikat—NARMADASHA (vii) Farbasveerah—DALPATRAM (viii) Saraswatichandra-Part 1—GOVARDHANRAM TRIPATHI (ix) Purvalap—‘KANT’ (MANISHANKAR RATNAJI BHATT) (x) Raino Parvat—RAMANBHAI NEELKANTH Section B 1. Gandhiyug & Anu Gandhiyug (i) Hind Swaraj—MOHANDAS KARAMCHAND GANDHI (ii) Patanni Prabhuta—KANHAIYALAL MUNSHI (iii) Kavyani Shakti—RAMNARAYAN VISHWANATH PATHAK (iv) Saurashtrani Rasdhar-Part 1—ZAVERCHAND MEGHANI (v) Manvini Bhavai—PANNALAL PATEL (vi) Dhvani—RAJENDRA SHAH 2. Adhunik yug (vii) Saptapadi—UMASHANKAR JOSHI (viii) Janantike—SURESH JOSHI (ix) Ashwatthama—SITANSHU YASHASCHANDRA . -

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1 Chapter: 1 Introduction Substantial research work has been conducted on the genre of the novel and its various aspects in English as well as in Gujarati literature, but the study focusing on the theme of the region and regionality in Indian writing in English and the Gujarati novel, especially in the novels of R. K. Narayan (1906 to 2001) and Pannalal Patel (1912 to 1989), has scarcely been carried out in a comparative mode. This dissertation is aimed at studying the representation of the region in the novels of R. K. Narayan and Pannalal Patel from the point of view of postcolonial studies by highlighting the socio-cultural, political and religious dimensions their works. It is possible to locate the postcolonial discourse of creating an image of indigenous culture through the means of representing rural locale, language and customs in the works of R. K. Narayan and Pannalal Patel. The creative period of both the novelists extends from the pre-independence to the post-independence phase of the twentieth century India. Their works cover majority of features representing the postcolonial dimension of literature, which has been examined in the following chapters. Narayan is regarded as the father-figure in postcolonial Indian English fiction. Similarly Pannalal Patel’s creativity writing too has a comparable place. Both represent the notion of region and nation which has become now-a-days vigorous debate in postcolonial studies. The thesis explores how the literary discourse of their novels participates in constructing ‘nation’ in a postcolonial context by representing ‘region’. Instead of seeing the categories of ‘nation’ and ‘region’ as simple opposites, the thesis examines the problematic ways in which these notions are represented. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name : Dr. Raghuvir Chaudhari Date of Birth : 1938 Address (Residential): A-6, Purneshwar Flats, Gulbai Tekra, Ahmedabad-380 015 Tel. No. : 9327726371 Website : http://iet.ahduni.edu.in/people-details/faculty- list/sanjay_chaudhary He did his M.A. in ‘Hindi language and literature’ from Gujarat University in 1962 and later obtained his Ph.D. from the same University in 1979. He retired on 15th June, 1998, as a Professor and Head of the Department of Hindi, Post-graduate School of Languages, Gujarat University. Eight students have obtained PhD degree under his guidance. Raghuveer Chaudhari had worked for adult-education in his village and also constructed a small library and a theatre for his school. During vacations, he used to work with social workers. He was very active in 'Navanirrnan Andolan' - an anti-corruption movement - against the State Government of Gujarat. With the same concern he had opposed ‘The Emergency’ which suppressed the freedom of expression in 1975. He was born and brought up in a religious family of farmers. His acquaintance with leading and devoted Gandhian friends as well as his farming background nourished the deep sense of social responsibility in him. This is the reason why his concept of modernism is different from those of his contemporaries. Raghuveer's talent was nurtured by the prose writings of Govardhanram Tripathi, Kaka Kalelkar, Suresh Joshi, Niranjan Bhagat and Priyakant Maniyar. He owes his early training to his teacher and friend Bholabhai Patel, a well-known scholar and man-of- letters in Gujarati. Later Raghuveer developed an interest in Hindi and Sanskrit studies. -

Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A Literary Review for the thesis Strategies for Translating Dialectical Features: A Study of Selected Gujarati Novels in English Translation Author: Co-author: Mihir Dave Dr. Paresh Joshi Assistant Professor Professor Department of Communication Skills Department of English Marwadi University – Rajkot Veer Narmad South Gujarat University – Surat V o l u m e . 4 I s s u e 3 D e c e m b e r - 2 0 1 8 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Introduction: The present research is aimed at exploring the strategies employed while translating dialectical features of Gujarati novels into English. Since a dialect is a regionally or socially distinctive variety of a language, it is identified by a particular set of words and phonological features. Spoken dialects are usually also associated with a distinctive pronunciation and accent. At times the two dialects of the same language become unintelligible to each other e.g. the dialects of Chinese: Mandarin, Cantonese etc. Cockney, one of the dialects of English, is considered ‘squeamish’ and ‘affected’ by the standard users of English. Similarly, a Gujarati dialect spoken in the Northern Gujarat is somewhat unintelligible to the people of Southern Gujarat. Now, while translating Gujarati novels with diverse varieties of dialectical features into English, what strategies of translation are employed by the translators could be an interesting study. A novel, set in a regional background, represents the race and milieu of that region. Such a novel is written in a dialectical language to express the unique features of that region. -

Prospectus 2017-2018

FACULTY OF ARTS THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA Accredited Grade ‘A’ by NAAC PROSPECTUS 2017-2018 WE PAY OUR TRIBUTES and RESPECT TO THE GREAT VISIONARY H. H. MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO GAEKWAD III … in whose name we cherish the name of this Temple of Education … we recall the Mission and Vision as perceived by Him …. “The progress of a nation requires that its people should be educated. Knowledge is a necessity of man. It instills in him a desire to question and to investigate, which leads him on the path of progress. Education, in the broadest sense, must be spread everywhere. Progress can only be achieved by the spread of education. Cooperation is necessary to achieve any worthy end and this readiness to cooperate will not be found in a people, if they are not educated.” Professor K. Krishnan Dean, Faculty of Arts Dear Students, At the very outset, I welcome you all to the various programmes of studies, offered by the Faculty of Arts and I wish you a very rewarding academic and co-scholastic life on this campus. My colleagues have taken great care in preparing this Prospectus, and we hope that the information contained herein will guide you through the Choice Based Credit System, which the Faculty of Arts introduced during 2011-12. We wish that you read all the rules very carefully and understand the salient features, requirements, obligations and all such related matters well before you embark on filling up the form for admission. It is my pleasant duty to inform you that my colleagues at various departments will be glad to extend any clarifications; be in terms of queries or guidance / advice, whom you may approach at their respective departments during office hours. -

Roomy F. Naqvy Assistant Professor MA (English) 1994 Jamia Millia

Name: Roomy F. Naqvy Assistant Professor M.A. (English) 1994 Jamia Millia Islamia M. Phil. (English Literature) 1996 Jamia Millia Islamia JRF – NET December 1993 Awards: Recipient of Katha Translation Award (Gujarati) 1996 Academic Highlights Invited to a UGC SAP National Seminar on Representations of Community, Culture, and Ideology in the Post-1970s Gujarat, Hindi, and Indian English Literatures at the Department of English, Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat, in March 2009, where I presented a paper and chaired a session. Invited to Rajkot, Gujarat, as expert in a Workshop on Translation, April 2003. Presented a paper on Literary Translation “Translating Literature, Translating Oneself” at the First ProZ.com Annual Convention in Porto Santo Stefano, Italy, on 21 September 2001. Served as Panel Discussant in Translating India, a Seminar organized by Sahitya Akademi, National Academy of Letters, New Delhi from 15-17 January 2001. Attended a course on Effective Communication at Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur in July 1998. Presented the paper "Decolonising the Canon: Dislocating Indian Poetry in English from the Pincer Grip of Post-colonial Studies", at the National Seminar on Rethinking Indian English Literature organized by the Department of English, M. S. University of Baroda from February 14-18, 1998. Select Publications: Research Articles "The Silence/ Speech Dialectic: A Textual Study of Suresh Joshi's 'Dwiragaman'" in Indian Literature 181 (Sept.-Oct. 1997), pp. 133-34. [Article on a modernist Gujarati short story.] "A Poetics of Space" (a textual study of Ramanujan's poem "The Striders") in Indian Literature 173 (May- June 1996), pp. 145-46. -

Culture of Translation Most Literature, Whether Classical Or Modern

Culture of Translation Gulammohammed Sheikh Most literature, whether classical or modern, eastern or western, comes to us through translations. We have read our Ibsen and Dostoyevsky, Sartre and Marquez in English translations. To many of us Takazhi or Tagore are accessible only in English. Those who read translations, in for instance Kannada or Kashmiri, might find that these were made from English translations of the original. It brings to the fore a couple of important observations. First, that the text you read is twice removed from the original both linguistically and culturally, and second, that no language other than English cuts across the linguistic barriers between the north and the south. So, the questions of inter-language translation remain somewhat vexed. I understand a vast body of translations exists published in regional languages. In the absence of available data, it is difficult to know whether these were made directly from the language in which the book was written or through the mediation of English (I am told that no survey of this kind has been conducted so far!*). Most of such books are published by the central and regional Sahitya Akademis, the National Book Trust and a few private publishing houses on a regular basis, after being selected for annual awards or as classics. Translations of these into English serves the dual purpose of addressing the English audience and simultaneously facilitation their translations into other Indian languages. Of course it is more than likely that in some languages translations are made directly from the original or through mediatory languages other than English (again, no data is available). -

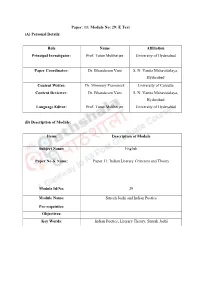

Paper: 11; Module No: 29: E Text (A) Personal Details

Paper: 11; Module No: 29: E Text (A) Personal Details: Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator: Dr. Bhandaram Vani S. N. Vanita Mahavidalaya, Hyderabad Content Writer: Dr. Mrinmoy Pramanick University of Calcutta Content Reviewer: Dr. Bhandaram Vani S. N. Vanita Mahavidalaya, Hyderabad Language Editor: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad (B) Description of Module: Items Description of Module Subject Name: English Paper No & Name: Paper 11: Indian Literary Criticism and Theory Module Id/No: 29 Module Name: Suresh Joshi and Indian Poetics Pre-requisites: Objectives: Key Words: Indian Poetics, Literary Theory, Suresh Joshi Suresh Joshi and his Contribution to Indian Poetics Introduction In his Indian Literary Criticism: Theory and Interpretation, Gnesh Devy commented, “What B.S. Mardhekar has been to Marathi, Suresh Joshi (1921-1986) has been to Gujarati”. He is one among the avant garde writers in Gujarati literature. He is pioneer to bring modernism in Gujarati Literature. Devy commented, his idea fails to be carried forward in Gujarati literature but his contribution to short fiction, literary prose and literary criticism is path breaking. He has immense contribution in bringing self-awareness in Gujarati literature. His contribution in the theory of fiction is remarkable. He propagated the idea of Ghatanavilop which is minimizing the plot and emphasizing on the ‘suggestive potential of language’. Devy took a part from Chintayami Manasa, translated by Upendra Nanavati to represent the literary thought of Joshi. And this piece talks about the theory of interpretation. History of Gujarati Literature The history of Gujarati literature may be traced to 1000 AD, and this literature has flourished since then to the present. -

Prospectus 2016-2017

FACULTY OF ARTS THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA PROSPECTUS 2016-2017 WE PAY OUR TRIBUTES and RESPECT TO THE GREAT VISIONARY H. H. MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO GAEKWAD III … in whose name we cherish the name of this Temple of Education … we recall the Mission and Vision as perceived by Him …. “The progress of a nation requires that its people should be educated. Knowledge is a necessity of man. It instills in him a desire to question and to investigate, which leads him on the path of progress. Education, in the broadest sense, must be spread everywhere. Progress can only be achieved by the spread of education. Cooperation is necessary to achieve any worthy end and this readiness to cooperate will not be found in a people, if they are not educated.” Professor Pradeep Singh Choondawat Dean, Faculty of Arts Dear Students, At the very outset, I welcome you all to the various programmes of studies, offered by the Faculty of Arts and I wish you a very rewarding academic and co- scholastic life on this campus. My colleagues have taken great care in preparing this Prospectus, and we hope that information contained herein will guide you through the Choice Based Credit System, which the Faculty of Arts introduced during 2011-12. We wish that you read all rules very carefully and understand the salient features, requirements, obligations and all such related matters well before you embark on filling up the form for admission. It is my pleasant duty to inform you that my colleagues at various departments will be glad to extend any clarifications; be in terms of queries or guidance / advice, whom you may approach to at their respective departments during office hours. -

Saraswatichandra: an Example of Structural Novelty in the Late 19Th Century Fiction in Gujarati Literature

GAP BODHI TARU A GLOBAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES ( ISSN – 2581-5857 ) Impact Factor: SJIF - 5.171, IIFS - 5.125 Globally peer-reviewed and open access journal. SARASWATICHANDRA: AN EXAMPLE OF STRUCTURAL NOVELTY IN THE LATE 19TH CENTURY FICTION IN GUJARATI LITERATURE Dr. Narendra K. Patel, Jigarkumar R Joshi Assi. Professor Shri P. K. Chaudhary Mahila Arts College, Gandhinagar. Research Scholar, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad. Abstract Besides being a landmark in popularising Novel as literary genre in Gujarati literature, Saraswatichandra can also be credited for the unparalleled and unprecedented structural nuances in Gujarati literature. Specific features of literary genres distinguish them from each other. Consciously or unconsciously, the authors sometimes adopt one genre’s characteristic in other. Govardhanram Tripathi’s magnum opus, Saraswatichandra is one such unprecedented instance in Gujarati literature where a novel, a prose work finds the feature of verse, an epic. Perhaps it is one of the reasons why it is considered as one of the masterpieces in Gujarati literature. In the present paper, the researchers try to shed some light on this structural novelty of confluence of two genres – Prose and Epic, making Saraswatichandra a Prose Epic of the age. Keywords: Saraswatichandra, Prose Epic, Epic, Govardhanram Tripathi, Gujarati Literature. INTRODUCTION The history of fiction in Gujarati literature is quite shorter compared to the West. Gujarati literature gets its first novel Karanghelo by Nandshankar Mehta in 1866 (Das 201) while the West found the seeds of fiction way back in the early 18th century. Novel as a form was not that much experimental and popular until Govardhanram Tripathi’s magnum opus Saraswatichandra (1887-1901) was published. -

Willful Defaulters – Bankwise List

WILLFUL DEFAULTERS – BANKWISE LIST Amount (Rs. Bank Borrower Name Directors Name Lacs) ALLAHABAD BANK PUNEET FASHION PVT LTD PUNNET BEDI, TILAK RAJ BEDI, NIKHIL BEDI 8671.00 Bharat Kr. Mangaldas kapadia, Rajesh Mangaldas Kapadia, Dinesh ALLAHABAD BANK Biotor Industries Ltd. 5000.00 Ranchhodas Kapadia ALLAHABAD BANK BELLPOLY MOULDERS P LTD Sanjeev Kapoor, Rajesh Kohli 4755.00 Vinita Sonthalia,PAN: AKTPS2471A, Asish Bothra,PAN: ALLAHABAD BANK Sukhsagar Infotech Pvt ltd 3547.00 AIWPB7094B Gunawati Devi Sonthalia, PAN: AJQPS5327K, Sudesh Kumar ALLAHABAD BANK Roto India Enterprise 3122.00 Sonthalia Sambhu Nath Agarwal, PAN: ACSPA4777C, Binit Agarwal,, Sri Amit ALLAHABAD BANK Utsav Rice Mills PVT Ltd 3092.00 Agarwal, Smt. Sikha Agarwal, PAN: AFBPA9980M ALLAHABAD BANK R S Vanijya Ltd Aman Saraogi, Manish Agarwal 3018.00 MAHENDRA KUMAR SURATMAL BHANSALI, RAMESH KUMAR ALLAHABAD BANK MODERN TUBE INDUSTRIES LTD 2611.00 CHUNILAL DOSHI, HIMANSHU SANTHAN SHARMA ALLAHABAD BANK SHREE VALLABH EXPORTS DHARAMPAL JAIN, JANINDER JAIN 2033.00 ALLAHABAD BANK SHREE VALLABH OVERSEAS DHARAMPAL JAIN, JANINDER JAIN 1930.00 ALLAHABAD BANK NIKHIL EXPORT PVT LTD NIKHIL BEDI, PUNNET BEDI, NEHA BEDI 1845.00 ALLAHABAD BANK A & J IMPEX ANJU JAIN 1394.00 ALLAHABAD BANK NEHA EXPORTS NEHA BEDI 1252.00 KAUSHIK KR. NATH,PAN: APJPN9762J, MANISHA NATH, PAN: ALLAHABAD BANK GOODVALUE TREXIM PVT LTD. 974.05 AHHPN8993M ALLAHABAD BANK RAJAN TRADING PVT LTD NAVNEET SINGH BEDI, DIPTENDU GIRI 934.00 ALLAHABAD BANK PCH life Style ltd Balvinder singh, PAN: ADVPS0174K 834.00 ALLAHABAD BANK KAPOOR EXPORTS DALJEET SINGH, JEEVAN KUMAR GUPTA 807.00 KAUSHIK KR. NATH, PAN: APJPN9762J, MANISHA NATH, PAN: ALLAHABAD BANK TIEUP TRADIND PVT LTD 780.00 AHHPN8993M KISHORE K. -

Gujarati.Pdf

GUJARATI NOVEL Chemmeen (Malayalam - A.W.) Havelini Andar (Inside the Haveli, By Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai English - A.W.) Translated by Kamal Jasapara By Rama Mehta Alpajeevi (Telugu) Pp. 192, First Edition : 1980 Rs. 25 Translated by Anila Dalal By Rachkonda V. Shastri Pp. 230, First Edition : 2003 Translated by Navnit Madrasi Chha Vighan Jameen ISBN 81-260-1568-3 Rs. 110 Pp. 182, First Edition : 1985 Rs. 25 (Chhaman Atha Guntha, Oriya) By Fakir Mohan Senapati Hun Aane Vanwihari Andh Digant (Oriya) Translated by Mira Bhatt (Ani O Banbehari, Bengali - A.W) By Surendra Mohanty Pp. 192, First Edition : 1982 Rs. 20 By Sandipan Chattopadhyay Translated by Renuka Soni Translated by Anita Dalal Pp. xx+246, First Edition : 2000 Chhaya Rekhao Pp. 58, First Edition : 2007 ISBN 81-260-1034-7 Rs. 140 (The Shadow Lines, English - A.W.) ISBN 81-260-2353-4 Rs. 60 By Amitao Ghosh Iyaruingam (Assamese - A.W.) Aranyak (Bengali) Translated by Shalini Topiwala By Birendra Kumar Bhattacharyya By Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay Pp. 264, First Edition : 1998 Translated by Bholabhai Patel Translated by Chandrakant Mehta ISBN 81-260-0376-6 Rs. 140 Pp. 268, First Edition : 1996 Pp. 262, Reprint : 2006 ISBN 81-7201-877-0 Rs. 120 ISBN 81-260-1036-3 Rs. 140 Daatu (Kannada - A.W.) By S.L. Bhyrappa Jogajog (Bengali) Arogya Niketan (Bengali - A.W.) Translated by Jaya Mehta By Rabindranath Tagore By Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay Pp. iv+520, First Edition : 1992 Translated by Shivkumar Joshi Translated by Ramnik Meghani ISBN 81-7201-145-8 Rs. 150 Pp. x+197, Reprint : 2001 Pp.