Ellery Queen: Forgotten Master Detective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

The Dutch Shoe Mystery

The Dutch Shoe Mystery Ellery Queen To DR. S. J. ESSENSON for his invaluable advice on certain medical matters FOREWORD The Dutch Shoe Mystery (a whimsicality of title which will explain itself in the course of reading) is the third adventure of the questing Queens to be presented to the public. And for the third time I find myself delegated to perform the task of introduction. It seems that my labored articulation as oracle of the previous Ellery Queen novels discouraged neither Ellery’s publisher nor that omnipotent gentleman himself. Ellery avers gravely that this is my reward for engineering the publication of his Actionized memoirs. I suspect from his tone that he meant “reward” to be synonymous with “punishment”! There is little I can say about the Queens, even as a privileged friend, that the reading public does not know or has not guessed from hints dropped here and there in Opus 1 and Opus 2.* Under their real names (one secret they demand be kept) Queen pere and Queen fits were integral, I might even say major, cogs in the wheel of New York City’s police machinery. Particularly during the second and third decades of the century. Their memory flourishes fresh and green among certain ex-offi- cials of the metropolis; it is tangibly preserved in case records at Centre Street and in the crime mementoes housed in their old 87th Street apart- ment, now a private museum maintained by a sentimental few who have excellent reason to be grateful. As for contemporary history, it may be dismissed with this: the entire Queen menage, comprising old Inspector Richard, Ellery, his wife, their infant son and gypsy Djuna, is still immersed in the peace of the Italian hills, to all practical purpose retired from the manhunting scene . -

An Intelligent Technique to Customise Music Programmes for Their Audience

Poolcasting: an intelligent technique to customise music programmes for their audience Claudio Baccigalupo Tesi doctoral del progama de Doctorat en Informatica` Institut d’Investigacio¶ en Intel·ligencia` Artificial (IIIA-CSIC) Dirigit per Enric Plaza Departament de Ciencies` de la Computacio¶ Universitat Autonoma` de Barcelona Bellaterra, novembre de 2009 Abstract Poolcasting is an intelligent technique to customise musical se- quences for groups of listeners. Poolcasting acts like a disc jockey, determining and delivering songs that satisfy its audience. Satisfying an entire audience is not an easy task, especially when members of the group have heterogeneous preferences and can join and leave the group at different times. The approach of poolcasting consists in selecting songs iteratively, in real time, favouring those members who are less satisfied by the previous songs played. Poolcasting additionally ensures that the played sequence does not repeat the same songs or artists closely and that pairs of consecutive songs ‘flow’ well one after the other, in a musical sense. Good disc jockeys know from expertise which songs sound well in sequence; poolcasting obtains this knowledge from the analysis of playlists shared on the Web. The more two songs occur closely in playlists, the more poolcasting considers two songs as associated, in accordance with the human experiences expressed through playlists. Combining this knowl- edge and the music profiles of the listeners, poolcasting autonomously generates sequences that are varied, musically smooth and fairly adapted for a particular audience. A natural application for poolcasting is automating radio pro- grammes. Many online radios broadcast on each channel a random sequence of songs that is not affected by who is listening. -

Ellery Queen Master Detective

Ellery Queen Master Detective Ellery Queen was one of two brainchildren of the team of cousins, Fred Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Dannay and Lee entered a writing contest, envisioning a stuffed‐shirt author called Ellery Queen who solved mysteries and then wrote about them. Queen relied on his keen powers of observation and deduction, being a Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson rolled into one. But just as Holmes needed his Watson ‐‐ a character with whom the average reader could identify ‐‐ the character Ellery Queen had his father, Inspector Richard Queen, who not only served in that function but also gave Ellery the access he needed to poke his nose into police business. Dannay and Lee chose the pseudonym of Ellery Queen as their (first) writing moniker, for it was only natural ‐‐ since the character Ellery was writing mysteries ‐‐ that their mysteries should be the ones that Ellery Queen wrote. They placed first in the contest, and their first novel was accepted and published by Frederick Stokes. Stokes would go on to release over a dozen "Ellery Queen" publications. At the beginning, "Ellery Queen" the author was marketed as a secret identity. Ellery Queen (actually one of the cousins, usually Dannay) would appear in public masked, as though he were protecting his identity. The buying public ate it up, and so the cousins did it again. By 1932 they had created "Barnaby Ross," whose existence had been foreshadowed by two comments in Queen novels. Barnaby Ross composed four novels about aging actor Drury Lane. After it was revealed that "Barnaby Ross is really Ellery Queen," the novels were reissued bearing the Queen name. -

Publisher Index

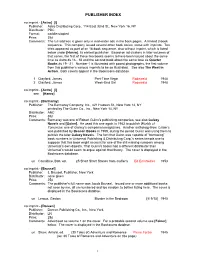

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels. -

Borges Y El Policial En Las Revistas Literarias Argentinas

Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica Number 77 Literatura Venezolana del Siglo XXI Article 30 2013 Whodunit: Borges y el policial en las revistas literarias argentinas Pablo Brescia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti Citas recomendadas Brescia, Pablo (April 2013) "Whodunit: Borges y el policial en las revistas literarias argentinas," Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica: No. 77, Article 30. Available at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti/vol1/iss77/30 This Nuevas Aproximaciones a Borges is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTI NO 77-78 WHODUNIT: BORGES Y EL POLICIAL EN LAS REVISTAS LITERARIAS ARGENTINAS Pablo Brescia University of South Florida Descreo de la historia, ignoro con plenitud la sociología, algo creo entender de literatura... Jorge Luis Borges 1. Borges contrabandista: sobre gustos hay mucho escrito Entre 1930 y 1956 se publican Evaristo Carriego, Discusión, Historia universal de la infamia, Historia de la eternidad, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan, Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi, Ficciones, El Aleph y Otras inquisiciones, entre otros libros. Durante este período, el más intenso y prolífico en su producción narrativa y crítica, Jorge Luis Borges propone una manera de leer y escribir sobre literatura que modifica no sólo el campo literario argentino sino también el latinoamericano. Esta tarea se lleva a cabo mediante lo que en otro lugar denominé “operaciones” literarias,1 en tanto designan intervenciones críticas y de creación que van armando una especie de red, contexto o incluso metarrelato desde el cual Borges puede ser, por lo menos desde una vía hermenéutica, leído según sus propios intereses estéticos. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington,D.C. National Library Service for the Blind andPhysically Handicapped. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0763-1 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 172p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Audiodisks; *Audiotape Recordings; Authors; *Blindness; *Braille;Government Libraries; Large Type Materials; NonprintMedia; *Novels; *Short Stories; *TalkingBooks IDENTIFIERS *Detective Stories; Library ofCongress; *Mysteries (Literature) ABSTRACT This document is a guide to selecteddetective and mystery stories produced after thepublication of the 1982 bibliography "Mysteries." All books listedare available on cassette or in braille in the network library collectionsprovided by the National Library Service for theBlind and Physically Handicapped of the Library of Congress. In additionto this largn-print edition, the bibliography is availableon disc and braille formats. This edition contains approximately 700 titles availableon cassette and in braille, while the disc edition listsonly cassettes, and the braille edition, only braille. Books availableon flexible disk are cited at the end of the annotation of thecassette version. The bibliography is divided into 2 Prol;fic Authorssection, for authors with more than six titles listed, and OtherAuthors section, a short stories section and a section for multiple authors. Each citation containsa short summary of the plot. An order formfor the cited -

![1941-12-20 [P B-12]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2154/1941-12-20-p-b-12-1862154.webp)

1941-12-20 [P B-12]

AMUSEMENTS. Now It's Mary Martin's Turn Old Trick Is Where and When rn!TTTVWTrTr»JTM. Τ ■ Current Theater Attractions 1 To Imitate Cinderella and Time of Showing LAST 2 TIMES Used Again MAT. I:SO. NIGHT ·:3· Stape. The Meurt. Shubert Prêtent 'New York Town' Sounds Dramatic, But National—"The Mikado." by the In Met Film ! Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Co.: Turns Out to Be Considerably Less; 2:30 and 8:30 p.m. Gilbert &"SuHi»aii De Invisible Actors Screen. Wolfe Is — Billy Excellent Capitol "Swamp Water," ad- 0peta ÎÊompnmj venture In the By JAY CARMODY. Romp About in wilderness: 11:10 "THE MIKADO" a.m., 1:50, 4:30, 7:10 and 9:50 p.m. Next time Mary Martin and Fred MacMurray have to do Price»: IM»ï, SI.(Kl, SI.Se. Sî.Ofl, >1·· lu nothing shows: 1:05, 6:25 and they better run away and hide. Then when Paramount has notions of Stage 3:45, 'Body Disappears' 9:05 a like "New York p.m. NEXT WEEK—SEATS NOW making picture Town," it won't have any stars at hand "Th· Body Disappears," Warner Columbia—"Shadow of the Thin Munie»! Comedy Hit and the impulse will die. Better that than that the should. Bro·. photoplay featuring Jenry Lynn. George Abbott's picture more about For all the Jane Wyman and Edward Everett Horton: Man," Mr. and Mrs. VIVIENNE SEGAL—GEORGE TAPPI drama, excitement and grandeur suggested by the title, by Bryrti Toy: directed by Ross produced Nick Charles: 11:20 a.m., 1:30, 3:45, New York Town" actually is the Cinderella legend dragged out and in- Lederman; screenplay by Scott Darling and Erna Lazarus At the Metropolitan. -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

BOX DEWAAL TITLE VOL DATE EXHIBITS 1 D 4790 a Dime Novel

BOX DEWAAL TITLE VOL DATE EXHIBITS 1 D 4790 A Dime Novel Round-up (2 copies) Vol. 37, No. 6 1968 1 D 4783 A Library Journal Vol. 80, No.3 1955 1 Harper's Magazine (2 copies) Vol. 203, No. 1216 1951 1 Exhibition Guide: Elba to Damascus (Art Inst of Detroit) 1987 1 C 1031 D Sherlock Holmes in Australia (by Derham Groves) 1983 1 C 12742 Sherlockiana on stamps (by Bruce Holmes) 1985 1 C 16562 Sherlockiana (Tulsa OK) (11copies) (also listed as C14439) 1983 1 C 14439 Sherlockiana (2 proofs) (also listed C16562) 1983 1 CADS Crime and Detective Stories No. 1 1985 1 Exhibit of Mary Shore Cameron Collection 1980 1 The Sketch Vol CCXX, No. 2852 1954 1 D 1379 B Justice of the Peace and Local Government Review Vol. CXV, No. 35 1951 1 D 2095 A Britannia and Eve Vol 42, No. 5 1951 1 D 4809 A The Listener Vol XLVI, No. 1173 1951 1 C 16613 Sherlock Holmes, catalogue of an exhibition (4 copies) 1951 1 C 17454x Japanese exhibit of Davis Poster 1985 1 C 19147 William Gilette: State by Stage (invitation) 1991 1 Kiyosha Tanaka's exhibit, photocopies Japanese newspapers 1985 1 C 16563 Ellery Queen Collection, exhibition 1959 1 C 16549 Study in Scarlet (1887-1962) Diamond Jubilee Exhibition 1962 1 C 10907 Arthur Conan Doyle (Hench Collection) (2 copies) 1979 1 C 16553 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Collection of James Bliss Austin 1959 1 C 16557 Sherlock Holmes, The Man and the Legend (poster) 1967 MISC 2 The Sherlock Holmes Catalogue of the Collection (2 cop) n.d. -

FV Master Title 3/29/14.Numbers

Fellowship Village Senior Living Library Master List !1" Alphabetized by title -3/29/14" Brickell, Christopher A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants Ref Strout, Elizabeth Abide with me missing fic Levin, Phyllis Lee Abigail Adams Bio Trillin, Calvin About Alice Bio Norwich, John Julius Absolute Monarchs: a History of the Papacy Hist Vincenzi, Penny Absolute scandal, An fic Oates, Joyce Carol Accursed, The M&T Scottoline, Lisa Accused M&T Bellow, Saul Adventures of Augie March, The fic Coudert, Jo Advice from a failure health Child, Lee Affair, The M&T Forsyth, Frederick Afghan, The M&T Moore, Mary Tyler After all Bio Anderson, Christopher After Diana Bio Sheldon, Sidney After the darkness LP Morgan, Janet Agatha Christie Bio Fields, Jennie Age of desire, The fic Walker, Karen Thompson Age of miracles, The fic Greenspan, Alan Age of Turbulence, The Bio Holmes, Richard Age of wonder, The Rh Macintyre, Ben Agent Zigzag Hist Macy, Mike Alaska Oversize Brokaw,Tom Album of memories Hist Coelho, Paulo Aleph fic Patterson, James Alex Cross, run LP Berry, Steve Alexandria link M&T Hoag, Tami Alibi man LP Cordery, Stacy A. Alice:Alice Roosevelt Longworth Bio Flagg, Fannie All girl filling station’s last reunion, The LP Barnet, Andrea All night party Hist Freethy, Barbara All she ever wanted fic Sebold, Alice Almost moon, The LP Cawley, James & Margaret Along the Delaware and Raritan Canal NJ Cawley, James Along the Old York Road NJ American Heritage Am. Heritage history of the 1920’s & 1930’s Hist Tyler, Anne Amateur marriage fic Time Life Amazon, The Travel Fellowship Village Senior Living Library Master List !2" Alphabetized by title -3/29/14" Time, Inc.