The Dutch Shoe Mystery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embracing Change: Towards a Research-Led Learning Community

Embracing Change: Towards a Research-Led Learning Community Keynote speaker Sugata Mitra speaks about the future of education (transcript) October 27, 2017 Firstly, I’m very happy to be here, in this remarkable city and at this remarkable school. And I appreciate the fact that you’re trying to do something about the future—not many do. Particularly in education we have this great inertia. It doesn’t change. So if you’re a school principal, and you figure I need to change something, you’re worried that if you shake the system, a lot of people might object—the parents firstly, the politicians and sometimes even the teachers. Somehow, when it comes to education there are two things that go wrong. One is that we quite irrationally believe that our children should be educated the way we were educated. It doesn’t make any sense actually, but if you search inside, you’ll find a little voice that says, “That’s safe because I’m not a lunatic—as yet—so if my child goes through the same system, then maybe he or she will be alright.” The system doesn’t—and by the system, I mean the political system or the rulers—they don’t want to upset people. And the easiest way to upset people is to mess around with their children. So they lay off. You might have noticed if you look at politics around the world, every politician that comes to power, before coming to power says, “I will make sweeping changes in education.” And immediately after coming to power, they get busy with wars and that sort of thing. -

Detective Special Agent = DET. =SA Assistant

Detective = DET. Special Agent =SA Assistant Prosecuting Attorney =APA Unknown Male One= UM1 Unknown Male Two- UM2 Unknown Female= UF Tommy Sotomayor= SOTOMAYOR Ul =Unintelligible DET. Today is Thursday, November 6, 2014 and the time is 12:10 p.m. This is Detective with the St. Louis County Police Department's Bureau of Crimes Against Persons, . I'm here in a conference room, in the Saint Louis County Prosecuting Attorney's Office, with a, Special Agent, Special Agent of the F.B.I., and also present in the room is ... Sir, would you say your name for the recorder please? DET. Okay, and it's is that correct? That's correct. DET. Okay ... and what is your date of birth, ? DET. ...and your home address? DET. And do you work at all? DET. Do not. DET. Okay ... and what is your cell phone? What is my what now? DET. Cell phone? Number? DET. Yes Sir. DET. Okay and, a, did you say an apartment number with that? DET okay. mm hmm. DET. So ... you came down here, a, to the Prosecuting Attorney's Office, because you received a Grand Jury Subpoena, is that correct? That is correct. DET Okay and you received that Grand Jury Subpoena a few days ago? Yes. DET. Okay ... and since then, you had a conversation with a, at least one of the Prosecutors here, explaining to you that they would like you to come down to the office today, is that correct? Yes. DET. Okay, uhh ... having said that, a, I think your attendance at the Grand Jury will be later on this afternoon, or, or in a little bit here. -

Ellery Queen Master Detective

Ellery Queen Master Detective Ellery Queen was one of two brainchildren of the team of cousins, Fred Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Dannay and Lee entered a writing contest, envisioning a stuffed‐shirt author called Ellery Queen who solved mysteries and then wrote about them. Queen relied on his keen powers of observation and deduction, being a Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson rolled into one. But just as Holmes needed his Watson ‐‐ a character with whom the average reader could identify ‐‐ the character Ellery Queen had his father, Inspector Richard Queen, who not only served in that function but also gave Ellery the access he needed to poke his nose into police business. Dannay and Lee chose the pseudonym of Ellery Queen as their (first) writing moniker, for it was only natural ‐‐ since the character Ellery was writing mysteries ‐‐ that their mysteries should be the ones that Ellery Queen wrote. They placed first in the contest, and their first novel was accepted and published by Frederick Stokes. Stokes would go on to release over a dozen "Ellery Queen" publications. At the beginning, "Ellery Queen" the author was marketed as a secret identity. Ellery Queen (actually one of the cousins, usually Dannay) would appear in public masked, as though he were protecting his identity. The buying public ate it up, and so the cousins did it again. By 1932 they had created "Barnaby Ross," whose existence had been foreshadowed by two comments in Queen novels. Barnaby Ross composed four novels about aging actor Drury Lane. After it was revealed that "Barnaby Ross is really Ellery Queen," the novels were reissued bearing the Queen name. -

Tomorrow You Will Be Thinking About the Future Dana Dal Bo

TOMORROW YOU WILL “Genius. The ethereal beauty shines through, yet there is a constant, the constant of our primal fear, the primal scream denied, she rises, as we BE THINKING all should rise, magnificent and closer to God.” -Anonymous on 2012-02-13 17:07:37 Yuvutu “Bravo! usually one must drop acid to see such a sight. ABOUT Thank you for the trip (and saving me the cash) acid is getting rreally expensive. Ps. Playing Pink Floyd in the background (in reverse) would have been THE FUTURE a nice touch. -Crazy Larry on 2012-02-14 03:47:22 Yuvutu “Your work is amazing. Far beyond what you would expect from a porn site.” -faceboynyc on 2016-12-07 04:33:22 “j aime beaucoup c’est tordu et sexy à la fois sans vouloir te vexer” DANA DAL BO -comalot on 2017-01-08 05:15:09 TOMORROW YOU WILL BE THINKING ABOUT THE FUTURE DANA DAL BO January 20, 2017 www.danadalbo.com underskirt_ IN EXHIBITION Mirror, Monitor, Screen 2015 self-Less 2014-ongoing Marginal Cons(T)ent 2012-ongoing Disoriented Whore Trapped in Closet 2012 Leggy Barely Legal Goddess 2013 No ©opyright Intended 2017-1992 Contact Sheet 2017-1992 ...Still in the Running towards Becoming... 2014 Carbon Copy 2016 Tomorrow I Will Be Thinking About the Future 2013 THE ENTRANCE PART ONE : THE MIRROR NARCISSISM INFINITY VERACITY IDENTITY SELF SELFLESS SELFIE PART TWO : THE MONITOR SCOPOPHILIA MESMERISM HYSTERIA CENSORSHIP AUTHORITY CONSENT PART THREE : THE SCREEN TELEVISIONARY PIRACY MARS MAGNATE INCURSORATED SURVEILLANCE THE ESCAPE THE ENTRANCE Once upon a time there was limited stimulation (distraction) and an abundance of hours. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington,D.C. National Library Service for the Blind andPhysically Handicapped. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0763-1 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 172p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Audiodisks; *Audiotape Recordings; Authors; *Blindness; *Braille;Government Libraries; Large Type Materials; NonprintMedia; *Novels; *Short Stories; *TalkingBooks IDENTIFIERS *Detective Stories; Library ofCongress; *Mysteries (Literature) ABSTRACT This document is a guide to selecteddetective and mystery stories produced after thepublication of the 1982 bibliography "Mysteries." All books listedare available on cassette or in braille in the network library collectionsprovided by the National Library Service for theBlind and Physically Handicapped of the Library of Congress. In additionto this largn-print edition, the bibliography is availableon disc and braille formats. This edition contains approximately 700 titles availableon cassette and in braille, while the disc edition listsonly cassettes, and the braille edition, only braille. Books availableon flexible disk are cited at the end of the annotation of thecassette version. The bibliography is divided into 2 Prol;fic Authorssection, for authors with more than six titles listed, and OtherAuthors section, a short stories section and a section for multiple authors. Each citation containsa short summary of the plot. An order formfor the cited -

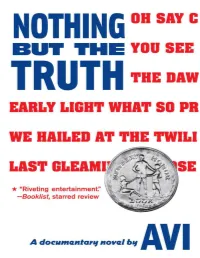

Nothing but the Truth Was First Published, I Had Trouble Getting a Reaction from the People It Was Written For: Kids

For Betty Miles Contents Title Page Dedication Preface 1 Tuesday, March 13 2 Thursday, March 15 3 Friday, March 16 4 Monday, March 19 5 Tuesday, March 20 6 Wednesday, March 21 7 Friday, March 23 8 Monday, March 26 9 Tuesday, March 27 10 Wednesday, March 28 11 Thursday, March 29 12 Friday, March 30 13 Saturday, March 31 14 Sunday, April 1 15 Monday, April 2 16 Tuesday, April 3 17 Wednesday, April 4 18 Friday, April 6 19 Monday, April 9 After Words™ About the Author Q&A with Avi “The Star-Spangled Banner” Two True, One False Three Sides of the Same Coin A Sneak Peek at Something Upstairs Also Available Copyright When Nothing But the Truth was first published, I had trouble getting a reaction from the people it was written for: kids. Teachers were taking the book and passing it around among themselves, insisting that their principals, assistant principals, and superintendents read it. Moreover, wherever I traveled, teachers would take me aside and say something like, “I know this book is about what happened in my school. Who was it who told you about what happened?” A principal once asked me if someone sent me his memos. A teacher from a school named Harrison High handed me a sheet of school stationery. The school’s logo was the lamp of learning that appears in the book. It got so that when I spoke to groups of teachers about the book, I took to asking, “Has anyone NOT heard of such an incident happening in your schools?” No one ever raised a hand. -

![1941-12-20 [P B-12]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2154/1941-12-20-p-b-12-1862154.webp)

1941-12-20 [P B-12]

AMUSEMENTS. Now It's Mary Martin's Turn Old Trick Is Where and When rn!TTTVWTrTr»JTM. Τ ■ Current Theater Attractions 1 To Imitate Cinderella and Time of Showing LAST 2 TIMES Used Again MAT. I:SO. NIGHT ·:3· Stape. The Meurt. Shubert Prêtent 'New York Town' Sounds Dramatic, But National—"The Mikado." by the In Met Film ! Gilbert and Sullivan Opera Co.: Turns Out to Be Considerably Less; 2:30 and 8:30 p.m. Gilbert &"SuHi»aii De Invisible Actors Screen. Wolfe Is — Billy Excellent Capitol "Swamp Water," ad- 0peta ÎÊompnmj venture In the By JAY CARMODY. Romp About in wilderness: 11:10 "THE MIKADO" a.m., 1:50, 4:30, 7:10 and 9:50 p.m. Next time Mary Martin and Fred MacMurray have to do Price»: IM»ï, SI.(Kl, SI.Se. Sî.Ofl, >1·· lu nothing shows: 1:05, 6:25 and they better run away and hide. Then when Paramount has notions of Stage 3:45, 'Body Disappears' 9:05 a like "New York p.m. NEXT WEEK—SEATS NOW making picture Town," it won't have any stars at hand "Th· Body Disappears," Warner Columbia—"Shadow of the Thin Munie»! Comedy Hit and the impulse will die. Better that than that the should. Bro·. photoplay featuring Jenry Lynn. George Abbott's picture more about For all the Jane Wyman and Edward Everett Horton: Man," Mr. and Mrs. VIVIENNE SEGAL—GEORGE TAPPI drama, excitement and grandeur suggested by the title, by Bryrti Toy: directed by Ross produced Nick Charles: 11:20 a.m., 1:30, 3:45, New York Town" actually is the Cinderella legend dragged out and in- Lederman; screenplay by Scott Darling and Erna Lazarus At the Metropolitan. -

BOX DEWAAL TITLE VOL DATE EXHIBITS 1 D 4790 a Dime Novel

BOX DEWAAL TITLE VOL DATE EXHIBITS 1 D 4790 A Dime Novel Round-up (2 copies) Vol. 37, No. 6 1968 1 D 4783 A Library Journal Vol. 80, No.3 1955 1 Harper's Magazine (2 copies) Vol. 203, No. 1216 1951 1 Exhibition Guide: Elba to Damascus (Art Inst of Detroit) 1987 1 C 1031 D Sherlock Holmes in Australia (by Derham Groves) 1983 1 C 12742 Sherlockiana on stamps (by Bruce Holmes) 1985 1 C 16562 Sherlockiana (Tulsa OK) (11copies) (also listed as C14439) 1983 1 C 14439 Sherlockiana (2 proofs) (also listed C16562) 1983 1 CADS Crime and Detective Stories No. 1 1985 1 Exhibit of Mary Shore Cameron Collection 1980 1 The Sketch Vol CCXX, No. 2852 1954 1 D 1379 B Justice of the Peace and Local Government Review Vol. CXV, No. 35 1951 1 D 2095 A Britannia and Eve Vol 42, No. 5 1951 1 D 4809 A The Listener Vol XLVI, No. 1173 1951 1 C 16613 Sherlock Holmes, catalogue of an exhibition (4 copies) 1951 1 C 17454x Japanese exhibit of Davis Poster 1985 1 C 19147 William Gilette: State by Stage (invitation) 1991 1 Kiyosha Tanaka's exhibit, photocopies Japanese newspapers 1985 1 C 16563 Ellery Queen Collection, exhibition 1959 1 C 16549 Study in Scarlet (1887-1962) Diamond Jubilee Exhibition 1962 1 C 10907 Arthur Conan Doyle (Hench Collection) (2 copies) 1979 1 C 16553 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Collection of James Bliss Austin 1959 1 C 16557 Sherlock Holmes, The Man and the Legend (poster) 1967 MISC 2 The Sherlock Holmes Catalogue of the Collection (2 cop) n.d. -

The Emergence of American Mystery Writers

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Library Scholarship University Libraries 10-31-2016 The Atomic Renaissance: the Emergence of American Mystery Writers Beth Turcy Kilmarx Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/librarian_fac Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Kilmarx, Beth Turcy, "The Atomic Renaissance: the Emergence of American Mystery Writers" (2016). Library Scholarship. 29. https://orb.binghamton.edu/librarian_fac/29 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Examples of the First Golden Age Mystery Writers Clockwise from left: Agatha Christie, Dashiell Hammett, Earle Stanley Gardener, Margery Allingham , Freeman Wills Croft and Ngaio Marsh The First Golden Age of Mystery 1918 -1939 The traditional mystery story had: • A Great Detective, • A larger-than-life character, • A deductive brain solved the puzzle. Knox’s Ten Commandments of Mystery • The criminal must be mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know. • All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course. • Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable. • No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end. • No Chinaman must figure in the story. • No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right. -

Olivia Votava Undergraduate Murder, Mystery, and Serial Magazines: the Evolution of Detective Stories to Tales of International Crime

Olivia Votava Undergraduate Murder, Mystery, and Serial Magazines: The Evolution of Detective Stories to Tales of International Crime My greatly adored collection of short stories, novels, and commentary began at my local library one day long ago when I picked out C is for Corpse to listen to on a long car journey. Not long after I began purchasing books from this series starting with A is for Alibi and eventually progressing to J is for Judgement. This was my introduction to the detective story, a fascinating genre that I can’t get enough of. Last semester I took Duke’s Detective Story class, and I must say I think I may be slightly obsessed with detective stories now. This class showed me the wide variety of crime fiction from traditional Golden Age classics and hard-boiled stories to the eventual incorporation of noir and crime dramas. A simple final assignment of writing our own murder mystery where we “killed” the professor turned into so much more, dialing up my interest in detective stories even further. I'm continuing to write more short stories, and I hope to one day submit them to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and be published. To go from reading Ellery Queen, to learning about how Ellery Queen progressed the industry, to being inspired to publish in their magazine is an incredible journey that makes me want to read more detective novels in hopes that my storytelling abilities will greatly improve. Prior to my detective story class, I was most familiar with crime dramas often adapted to television (Rizzoli & Isles, Bones, Haven). -

By Josh Pachter from Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine

The First Two Pages: “50” By Josh Pachter From Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (November/December 2018) My first published work of fiction—“E.Q. Griffen Earns His Name,” written when I was sixteen—appeared in the December 1968 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. About two years ago, I realized that the golden anniversary of that first publication was approaching, and I decided to celebrate by bringing its protagonist back, half a century older, in an anniversary story. The first question I had to consider was: “Where would E.Q. Griffen be at the age of sixty-six, and what would he be doing?” That was an easy one, since my daughter Rebecca and I snuck an Easter-egg answer into our collaborative story, “History on the Bedroom Wall,” which appeared in EQMM’s “Department of First Stories” in 2009—making me, by the way, the only person who has ever appeared in that section of the magazine twice, first in 1968 and again forty-one years later! “History on the Bedroom Wall” is told in the first person by a student at Middlebury College in Vermont, and at one point the narrator mentions an English teacher named Professor Griffen, who Becca and I knew was my E.Q. Griffen, all growed up. So it seemed logical to open my anniversary story with Professor Ellery Queen Griffen sitting in his faculty office at Midd, preparing for an upcoming lecture. All I needed now was a crime for him to solve. Because the character is an hommage to the original Ellery Queen, I quickly gravitated toward a dying- message murder, since the “dying message” is perhaps the best known of Ellery Queen the author's plot devices. -

The French Powder Mystery

The French Powder Mystery Ellery Queen Foreword EDITOR’S NOTE: A foreword appeared in Mr. Queen’s last detective novel written by a gentleman designating himself as J. J. McC. The publishers did not then, nor do they now, know the identity of this friend of the two Queens. In deference to the author’s wish, however, Mr. McC. has been kind enough to pen once more a prefatory note to his friend’s new novels and this note appears below. I have followed the fortunes of the Queens, father and son, with more than casual interest for many years. Longer perhaps than any other of their legion friends. Which places me, or so Ellery avers, in the unfortu- nate position of Chorus, that quaint herald of the olden drama who craves the auditor’s sympathetic ear and receives at best his willful impatience. It is with pleasure nevertheless that I once more enact my role of prologue-master in a modern tale of murder and detection. This pleasure derives from two causes: the warm reception accorded Mr. Queen’s first novel, for the publication of which I was more or less responsible, under his nom de plume; and the long and sometimes arduous friendship I have enjoyed with the Queens. I say “arduous” because the task of a mere mortal. In attempting to keep step with the busy life of a New York detective Inspector and the intellectual activity of a bookworm and logician can adequately be described only by that word. Richard Queen, whom I knew intimately long before he retired, a veteran of thirty-two years service in the New York police department, was a dynamic little gray man, a bundle of energy and industry.