Cogitations Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

Loki: Sorcerer Supreme 385

LOKI: SORCERER SUPREME 385 CATES WALTA BELLAIRE RATED T+ $3.99US MARVEL.COM 3 8 5 1 1 7 59606 08809 6 3 8 5 2 1 7 59606 08809 6 MARVEL.COM $3.99 RATED US T+ VARIANT 385 STEPHEN STRANGE WAS A PREEMINENT SURGEON UNTIL A CAR ACCIDENT DAMAGED THE NERVES IN HIS HANDS. HIS EGO DROVE HIM TO SCOUR THE GLOBE FOR A MIRACLE CURE. INSTEAD, HE FOUND A MYSTERIOUS WIZARD CALLED THE ANCIENT ONE WHO TAUGHT HIM MAGIC AND THAT THERE ARE THINGS IN THIS WORLD BIGGER THAN HIMSELF. THESE LESSONS ENABLED STEPHEN TO BECOME THE SORCERER SUPREME, EARTH’S FIRST DEFENSE AGAINST ALL MANNER OF MAGICAL THREATS. HIS PATIENTS CALL HIM… LAST THOUGH LOKI HAS BEEN AN ADMIRABLE SORCERER SUPREME SINCE HE WON THE TIME... TITLE, STEPHEN STRANGE DECIDED HE WAS GETTING TOO CLOSE TO FINDING THE EXILE OF SINGHSOONA SPELL THAT TRANSFERS ALL THE WORLD’S MAGIC TO ITS CASTER, AND THAT STRANGE HAD HIDDEN IN THE SOUL OF HIS FRIEND, ZELMA STANTON, APPRENTICE TO THE SORCERER SUPREME. HE FEARED LOKI WOULD REMOVE THE EXILE…KILLING ZELMA. STRANGE STORMED ASGARD AND RECEIVED A GIFT OF MAGIC FROM THE WORLD TREE, RECRUITED THE ALLPOWERFUL SENTRY TO PAY THE PRICE FOR IT AND, THUS ARMED, ATTACKED LOKI. STILL, THE GOD OF LIES WAS NEARLY VICTORIOUS. BELIEVING THE FATE OF THE WORLD AND ZELMA TO BE ON THE LINE, STRANGE RELEASED THE VOIDTHE SENTRY’S DARK OPPOSITEFROM ITS PRISON IN THE SANCTUM SANCTORUM, AND HELD STILL WHILE IT POSSESSED HIM. “LOKI: SORCERER SUPREME” PART FIVE WRITER DONNY CATES ARTIST GABRIEL HERNANDEZ WALTA COLOR ARTIST JORDIE BELLAIRE SPECIAL THANKS TO DAVID B. -

Marvel-Phile: Über-Grim-And-Gritty EXTREME Edition!

10 MAR 2018 1 Marvel-Phile: Über-Grim-and-Gritty EXTREME Edition! It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It 90s, but you’d be wrong. Then we have Nightwatch, a was a dark time for the Republic. In short, it was...the bald-faced ripoff of Todd MacFarlane’s more ‘90s. The 1990s were an odd time for comic books. A successful Spawn. Next, we have Necromancer… the group of comic book artists, including the likes of Jim Dr. Strange of Counter-Earth. And best for last, Lee and hate-favorite Rob Liefield, splintered off from there’s Adam X the X-TREME! Oh dear Lord -- is there Marvel Comics to start their own little company called anything more 90s than this guy? With his backwards Image. True to its name, Image Comics featured comic baseball cap, combustible blood, a costume seemingly books light on story, heavy on big, flashy art (often made of blades, and a title that features not one but either badly drawn or heavily stylized, depending on TWO “X”s, this guy that was teased as the (thankfully who you ask), and a grim and gritty aesthetic that retconned) “third Summers brother” is literally seemed to take all the wrong lessons from renowned everything about the 90s in comics, all rolled into one. works such as Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns. Don’t get me wrong, there were a few gems in the It wasn’t long until the Big Two and other publishers 1990s. Some of my favorite indie books were made hopped on the bandwagon, which was fueled by during that time. -

The Muppets Take the Mcu

THE MUPPETS TAKE THE MCU by Nathan Alderman 100% unauthorized. Written for fun, not money. Please don't sue. 1. THE MUPPET STUDIOS LOGO A parody of Marvel Studios' intro. As the fanfare -- whistled, as if by Walter -- crescendos, we hear STATLER (V.O.) Well, we can go home now. WALDORF (V.O.) But the movie's just starting! STATLER (V.O.) Yeah, but we've already seen the best part! WALDORF (V.O.) I thought the best part was the end credits! They CHORTLE as the credits FADE TO BLACK A familiar voice -- one we've heard many times before, and will hear again later in the movie... MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) And lo, there came a day like no other, when the unlikeliest of heroes united to face a challenge greater than they could possibly imagine... STATLER (V.O.) Being entertaining? WALDORF (V.O.) Keeping us awake? MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) Look, do you guys mind? I'm foreshadowing here. Ahem. Greater than they could possibly imagine... CUT TO: 2. THE MUPPET SHOW COMIC BOOK By Roger Langridge. WALTER reads it, whistling the Marvel Studios theme to himself, until KERMIT All right, is everybody ready for the big pitch meeting? INT. MUPPET STUDIOS The shout startles Walter, who tips over backwards in his chair out of frame, revealing KERMIT THE FROG, emerging from his office into the central space of Muppet Studios. The offices are dated, a little shabby, but they've been thoroughly Muppetized into a wacky, cozy, creative space. SCOOTER appears at Kermit's side, and we follow them through the office. -

Marvel Universe RPG Characters Costs Compiled by Cwylric (A.K.A

Marvel Universe RPG Characters Costs Compiled by Cwylric (a.k.a. D. Jon Mattson) Character Abilities Actions Modifiers Gear Challenges Total Abomination 28w 1r 12w 27w 0w -6w 61w 1r Baron Mordo 11w 91w 7w 0w -5w 104w Beast 18w 39w 5w 0w -8w 54w Black Cat 7w 11w 2r 22w 0w -2w 38w 2r Blob 22w 2r 12w 2r 15w 0w -7w 43w 1r Bullseye 11w 15w 19w 0w -6w 39w Captain America 11w 2r 20w 11w 26w -2w 66w 2r Cyclops 6w 23w 2r 1w 0w -6w 24w 2r Daredevil 9w 27w 18w 1r 3w -4w 53w 1r Doctor Doom 14w (7w 1r) 57w (8w) 12w (6w 2r) 0w -7w (-8w) 90w Doctor Octopus 15w 19w 4w 12w 2r -4w 46w 2r Doctor Strange 12w 135w 11w 20w(+) -3w 175w(+) Elektra 8w 35w 4w 1r 0w -2w 45w 1r Gambit 6w 1r 57w 1w 1r 0w -7w 57w 2r Green Goblin 18w 34w 14w 30w 2r -8w 88w 2r Jean Grey 10w 1r 63w 2r 2r 0w -5w 69w 2r Hulk 55w 2r (4w) 1w 1r (20w 1r) 50w (0w) 0w -12w 119w 1r Human Torch 6w 44w 3w 1r 0w -2w 51w 1r Invisible Woman 5w 2r 31w 1r 1w 0w -2w 36w Iron Man 15w (14w 1r) 58w 1r (48w 2r) 9w (31w) 0w -3w (-8w) 165w 1r Kang 9w 2r (10w 2r) 38w (19w 2r) 16w (7w) 0w(+) -5w (-10w) 86w(+) Kingpin 14w 1r 20w 2r 9w 13w -5w 52w Loki 36w 129w 26w 4w -7w 188w Magneto 21w 2r 82w 1r 9w 2r 7w -6w 114w 2r Mr. -

MANUAL of MYSTICISM PD F Version 1.0

Book 2: MANUAL OF MYSTICISM PD F Version 1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................2 Miscellaneous Spells ....................................................27 Magic in General.............................................................2 Magical Items ...............................................................29 Dimensions ..................................................................6,7 Locations of Importance...............................................37 Entities and Entreating .................................................16 Cults..............................................................................38 Specific Entities ...........................................................18 Index .............................................................................40 Credits Designed by Canting Kim Eastland Edited by Epigraphic Ed Sollers (Books 1 and 2) and Erudite Eric Tobias (Book 3) Cover by Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin, TSR, Inc. Colored by Jeff Butler POB 756 Interior artwork by the Marvel Bullpen and Jeff Butler Lake Geneva, WI 53147 Graphic Design by Steve Winter TSR, Inc. ISBN 0-88038-278-3 PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION™ 39 4 - 5 5 4 2 3 - X T S R 1 2 0 0 Typography by Betty Elmore Thanks to Peter Sanderson and Carl Potts for some clarifications. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any rep roduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is proh i b- ited without the -

“I Love You 3000” an Analysis of the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Emilie Højer Jørgensen and Maya Majgaard Herr Steen Ledet Christiansen Engelsk speciale 2 June 2020 Aalborg University “I love you 3000” An analysis of the Marvel Cinematic Universe Jørgensen & Herr 2 Abstract In this thesis, we will examine if the Marvel Cinematic Universe can be considered complex. We will analyse the following films Captain America: Civil War, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, and Avengers: Endgame which are all from Marvel Cinematic Universe’s third phase. We have chosen these films because they are connected in terms of storylines, characters, and worlds. We will focus on transmedia storytelling, seriality, kernels and satellites, worldbuilding, and complex media in order to examine the complexities within the films. Traditionally, transmedia storytelling is defined as one continuous story across multiple instalments and platforms. Two important aspects of transmedia storytelling are seriality and worldbuilding, where seriality deals with how stories are told across instalments and worldbuilding deals with how a fictional world is created and what it takes to make a fictional world believable. Kernels and satellites deal with major and minor events that occur in a narrative text and how they impact each other and complex media deals with how popular culture is becoming more and more complex because of multiple storylines that occur in different mediums. It is through these concepts that we will analyse the complexities within the films. Civil War and the two Avengers films are very serial because they are linked together through information and events that continue from previous films. The three films require the viewers to be familiar with the universe beforehand because they rely heavily on characters, storylines, and events from previous films. -

REALMS of MAGIC Book 3: CODEX of CHARACTERS and CREATURES by Kim Eastland PD F Version 1.0 TABLE of CONTENTS INTRODUCTION

REALMS OF MAGIC Book 3: CODEX OF CHARACTERS AND CREATURES by Kim Eastland PD F Version 1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................1 D’SPAYRE .......................................................................8 BARON MORDO.............................................................2 MAGIK.............................................................................8 BROTHER VOODOO ......................................................2 MORGAN LE FEY ...........................................................9 CLEA ..............................................................................3 NIGHTMARE...................................................................9 DIABLO ..........................................................................4 SHAMAN AND TALISMAN................................10 and 11 DOCTOR DOOM.............................................................5 SILVER DAGGER ..........................................................12 DOCTOR DRUID.............................................................4 UMAR............................................................................12 DOCTOR STRANGE .......................................................6 MAGICAL CREATURES..............................13 through 16 DORMAMMU..................................................................7 IN T R O D U C T I O N Hail, persistent seeker of the arcane arts , powers or Book 2 for Dimensional decades in Marvel adventures, the char- and welcome to the third -

The Tropic Trapeze: Circus in Colonial India

The Tropic Trapeze: Circus in Colonial India Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig- Maximilians-Universität München vorgelegt von Anirban Ghosh Kolkata, India 2014 1 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Christopher Balme Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Tobias Döring Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 24.01.2014 2 Acknowledgements No labour of love is achieved single-handedly and this dissertation needed a lot of blessings from a lot of wonderful (if not exotic) people. Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Christopher Balme for his immense patience and generosity in handling my requests. His written suggestions were invaluable along with the conversations we had over these three years. Nic, the Co-ordinator for our project, was a genie for all of us. I would also like to thank Gero for innumerable evenings of serious discussions. Lisa, who is going to be the one of the best performance studies scholars, I thank for being my soul sister among other things. This dissertation is truly transnational because of its constant travels to Munich including the final stages of writing and no amount of gratitude can alleviate my debt towards Louisa in this regard. Atig, Anirban, Amitava and Neha and Priyanka were my pillars of strength (despite their cynicism). I would like to thank the numerous curators in the archives and museums where I worked. Special mention should also be made of Dr. William Rodenhuis who helped me navigate the labyrinths of Haartman’s Circus Collection in Amsterdam. Mr. Gille, from the Hagenbeck archive, was very helpful in locating exact Indian themes in the archive. -

39155 369E8e52840f888dd93c

Age of Ultron (AU) (crossover Amazing Spider-Man Annual, The. Anole 698 series) 698 See Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- Ant-Man (1st) 225, 226, 229, 231, Index Agent X 679 Man Annual, The 235, 236–37, 240–41, 300, 305, Agents of S. H. I. E. L. D. (TV Amazing Spider-Man Special, The. 317, 325, 485, 501–03, 628, 681. Italic numerals refer to pages of the series) 699. See also Captain See Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- See also Giant-Man; Goliath (1st); TASCHEN book 75 Years of Marvel America, Captain America: Man Special, The Henry (Hank) Pym; Wasp, The which include images. The Winter Soldier (movie); Amazing Spider-Man, The (book). See (1st); Yellowjacket (1st) S. H. I. E. L. D. Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- Ant-Man (2nd) 581, 591, 628, 653. A Aggamon 281 Man, The (book) See also Scott Lang “Amazing Case of the Human Torch, Aja, David 685, 697 “Amazing Spider-Man, The” (comic Ant-Man (3rd) 691 The” (short story) 55 Alascia, Vince 29, 63, 68, 100 strip). See Spider-Man, “Amazing Antonioni, Michelangelo 468 A.I.M. (Advanced Idea Alcala, Alfredo 574 Spider-Man, The” (comic strip) Apache Kid 120. See also Western Mechanics) 381 Alderman, Jack 73 Amazing Spider-Man, The (movie). Gunfighters (vols. 1–2) Aaron Stack 596. See also Machine Aldrin, Edwin (“Buzz”) 453 See Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- Apache Kid, The 106 Man Alex Summers 475. See also Havok Man, The (movie) Apocalypse 654 Aaron, Jason 691, 694 Alf 649 Amazing Spider-Man, The (TV Apollo 11 453 ABC (American Broadcasting Alias (live TV version) 699 series) (1977–79). -

Strange Origin Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DOCTOR STRANGE: STRANGE ORIGIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Greg Pak,Emma Rios | 144 pages | 25 Nov 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785163916 | English | New York, United States Doctor Strange: Strange Origin PDF Book Home 1 Books 2. He discovers the source of the disturbance to be the Empirikul , a group of science worshipers hell-bent on exterminating all magic throughout the multiverse. And those tricky corners are cut square and sharp with ever so slight blunting permitted. Doctor Strange was created by the writer Stan Lee and artist Steve Ditko and made his first ever appearance in Strange Tales in The miniseries Strange 1- 6 Nov, — April , written by J. Strange circumvented this restriction by communicating to his wife Clea after he was beheaded for treason by King James. Though it agonized him, Strange was left with no choice but to obey his teacher and slay him to prevent the holocaust Shuma-Gorath would have unleashed upon the world. Sanctum Sanctorum Doctor Mordrid. Sell now - Have one to sell? In the direct-to-video film made its debut to gain mixed reviews from different media. Dark Horse released a Doctor Strange statue for their line of vintage-style products. Facebook Twitter. Refer to eBay Return policy for more details. Gamerverse Spider-Man Peter Parker. As Sorcerer Supreme of Earth, the hero traveled to other dimensions and fought unique villains such as Nightmare, Eternity, and the dread Dormammu. Unaware of the Ancient One's awareness of the threat against him, Strange confronts Mordo about his treachery only to be bound by restraining spells to prevent him from warning the Ancient One or physically attacking Mordo. -

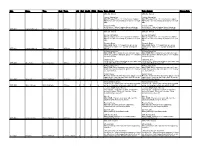

Current Change Date AFF-001 Captain Marvel Main Char

blac Name Type Cost Team Atk Def Health Flight Range Text - Original Text - Current Change Date AKA Ms. Marvel AKA Ms. Marvel Energy Absorption Energy Absorption Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your side. side. Woman of War Woman of War Level Up (4) - When Captain Marvel stuns an Level Up (4) - When Captain Marvel stuns an AFF-001 Captain Marvel Main Character A-Force 2 4 6 x x enemy character in combat, she gains an XP. enemy character in combat, she gains an XP. AKA Ms. Marvel AKA Ms. Marvel Energy Absorption Energy Absorption Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Main [Energy]: Put a +1/+1 counter on Captain Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your Marvel for each other [ranged] character on your side. side. Photonic Blast Photonic Blast Main [Skill]: Put a -1/-1 counter on an enemy Main [Skill]: Put a -1/-1 counter on an enemy character for each +1/+1 counter on Captain character for each +1/+1 counter on Captain AFF-002 Captain Marvel Main Character A-Force 4 6 6 x x Marvel. Marvel. A-Force Assemble! A-Force Assemble! Main [Skill]: When characters on your side team Main [Skill]: When characters on your side team attack the next time this turn, put a +1/+1 counter attack the next time this turn, put a +1/+1 counter on each of them.