Multicultural Literature in the United States Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

LIBRARY OPENS CENTER for YOUNG READERS by Kimberly Rieken

September - December 2009 LIBRARY OPENS CENTER FOR YOUNG READERS By Kimberly Rieken The Library of Congress, for the first time in its history, has a space devoted to the reading interests of children and teens in its historic Thomas Jefferson Building. On Oct. 23, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington welcomed a group of young people, parents and others to the new Young Readers Center, in Room LJ G-31, ground floor of the Thomas Jefferson Building. “We want you and other young readers to have a place where you can gain an introduction to the wonders of your nation’s library,” Billington told the children gathered in the center. The Librarian, with the help of Mrs. Billington, introduced the book “Moomin Troll” by Tove Jansson, from which the Billingtons read to the children. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., and her children and Rep. Robert Aderholt, R-Ala., and his son helped open the new center. A mother of three, the congresswoman said she was honored to be at the opening. “There’s nothing like an event in Washington with children,” she said. Stressing the importance of Center for the Book the Library for readers of all ages, she said, “We need to be able to inspire the Newsletter next generation of readers in the greatest library in the world.” Children gathered The Center for the Book’s around and listened intently as the congresswoman and her children read one of networks of state centers their favorite books, “Pinkalicious” by Elizabeth Kann and Victoria Kann. and reading promotion part- M.T. -

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

Listening to Gabriel García Márquez

PODCAST – “LA BIBLIOTECA” An exploration of the Library’s collections that focus on the cultures of Spain, Portugal, Latin America, and the Hispanic community in the US. SEASON 1/Episode 8 Listening to Gabriel García Márquez Catalina: ¡Hola! and welcome to “La biblioteca” An exploration of the Library of Congress’ collections that focus on the cultures of Spain, Portugal, Latin America, and the Hispanic community in the United States. I am Catalina Gómez, a librarian in the Hispanic Reading Room. Talía: And I am Talía Guzmán González, also a librarian in the Hispanic Reading Room. ¡Hola Catalina! CG: ¡Hola Talía! This is the last episode from this, our first season, which focused on some of our material from our Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape, a collection of audio recordings of poets and writers from the Luso-Hispanic world reading from their works which has been curated here at the Library of Congress. We truly hope that you have enjoyed our conversations and that you have become more interested and curious about Luso-Hispanic literature and culture through listening to our episodes. Today, we will be discussing our 1977 recording with Colombian Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez, or Gabo, as some of us like to call him (which is how we Colombians like to call this monumental author). TGG: We all like to call him el Gabo, in Latin America. He’s ours. CG: So García Márquez was born in Aracataca, Colombia in 1928. He is the author of more than ten novels and novellas, including Cien años de soledad, One Hundred Years of Solitud from 1967, El otoño del patriarca, The Autumn of the Patriarch, from 1975, and El amor en los tiempos del cólera, Love in the Time of Cholera from 1985. -

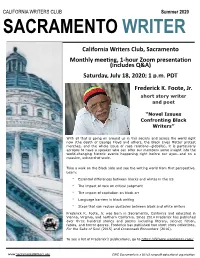

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

OLLI NEWS — May 14, 2021

OLLI NEWS — May 14, 2021 Summer Registration Is Open Books for Summer Classes Summer Zoom Trainings Spring SGL Gifts May 18 Lecture: Marie Arana May 20 Lecture: Daniel Goldman Summer & Fall Music-Theatre Group Virtual Music Event: Mozart & the King Bloomsday Celebration Virtual Tour: Rome, Italy Gandhi Center: Series on Indian Art F. Scott Fitzgerald Festival June Minis (6/7-7/2) June Minis meet once a week for 4 weeks over Zoom. Members can register for 3 courses for $100. We have moved the June Minis Lottery to Friday, May 21. Assignment letters will be e-mailed Friday or the following Monday. Last day for course changes and refunds is Friday, June 11. Requests for refunds must be made in writing (email is fine) by close of business, Friday, June 11. Register before Lottery Day, Friday, May 21. July Shorts (7/12-7/16) Shorts meet over Zoom 3, 4, or 5 times within the one week. Members can register for 3 courses for $75. The July Shorts Lottery will be held on Monday, June 21. Assignment letters will be e-mailed the following day. Last day for course changes and refunds is Friday, July 9. Requests for refunds must be made in writing (email is fine) by close of business, Friday, July 9. Register before Lottery Day, Monday, June 21. As usual, OLLI is working with Politics and Prose for books this summer. To purchase books for classes, members can do any of the following: Order from their website Call 202-364-1919 to order over the phone Visit Politics and Prose in person at 5015 Connecticut Ave NW If purchasing books via their website, mention in the notes field that the book is for an OLLI course. -

Torrey Peters Has Written the Trans Novel Your Book Club Needs to Read Now P.14

Featuring 329 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIX, NO. 1 | 1 JANUARY 2021 REVIEWS Torrey Peters has written the trans novel your book club needs to read now p.14 Also in the issue: Lindsay & Lexie Kite, Jeff Mack, Ilyasah Shabazz & Tiffany D. Jackson from the editor’s desk: New Year’s Reading Resolutions Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas As a new year begins, many people commit to strict diets or exercise regimes # Chief Executive Officer or vow to save more money. Book nerd that I am, I like to formulate a series MEG LABORDE KUEHN of “reading resolutions”—goals to help me refocus and improve my reading [email protected] Editor-in-Chief experience in the months to come. TOM BEER Sometimes I don’t accomplish all that I hoped—I really ought to have [email protected] Vice President of Marketing read more literature in translation last year, though I’m glad to have encoun- SARAH KALINA [email protected] tered Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults (translated by Ann Goldstein) Managing/Nonfiction Editor and Juan Pablo Villalobos’ I Don’t Expect Anyone To Believe Me (translated by ERIC LIEBETRAU Daniel Hahn)—but that isn’t exactly the point. [email protected] Fiction Editor Sometimes, too, new resolutions form over the course of the year. Like LAURIE MUCHNICK many Americans, I sought out more work by Black writers in 2020; as a result, [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor books by Claudia Rankine, Les and Tamara Payne, Raven Leilani, Deesha VICKY SMITH [email protected] Philyaw, and Randall Kenan were among my favorites of the year. -

The Cambridge Companion to Latina/O American Literature

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04492-0 - The Cambridge Companion to Latin A/O American Literature Edited by John Morán González Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Latina/o American Literature The Cambridge Companion to Latina/o American Literature provides a thorough yet accessible overview of a literary phenomenon that has been rapidly globalizing over the past two decades. It takes an innovative approach that underscores the importance of understanding Latina/o literature not merely as an ethnic phenomenon in the United States, but more broadly as a crucial element of a trans-American literary imagination. Leading scholars in the fi eld present critical analyses of key texts, authors, themes, and contexts, from the early nineteenth century to the present. They engage with the dynamics of migration, linguistic and cultural translation, and the uneven distribution of resources across the Americas that characterize the imaginative spaces of Latina/o literature. This Companion is an invaluable resource for understanding the complexities of the fi eld. John Morán González is Associate Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin, where he holds courtesy appointments with the Department of Mexican American and Latino Studies and the Department of American Studies. He is also a Faculty Affi liate of the Center for Mexican American Studies. His publications include The Troubled Union: Expansionist Imperatives in Post-Reconstruction American Novels and Border Renaissance: The Texas Centennial and the Emergence -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Race in the Age of Obama Making America More Competitive

american academy of arts & sciences summer 2011 www.amacad.org Bulletin vol. lxiv, no. 4 Race in the Age of Obama Gerald Early, Jeffrey B. Ferguson, Korina Jocson, and David A. Hollinger Making America More Competitive, Innovative, and Healthy Harvey V. Fineberg, Cherry A. Murray, and Charles M. Vest ALSO: Social Science and the Alternative Energy Future Philanthropy in Public Education Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences Reflections: John Lithgow Breaking the Code Around the Country Upcoming Events Induction Weekend–Cambridge September 30– Welcome Reception for New Members October 1–Induction Ceremony October 2– Symposium: American Institutions and a Civil Society Partial List of Speakers: David Souter (Supreme Court of the United States), Maj. Gen. Gregg Martin (United States Army War College), and David M. Kennedy (Stanford University) OCTOBER NOVEMBER 25th 12th Stated Meeting–Stanford Stated Meeting–Chicago in collaboration with the Chicago Humanities Perspectives on the Future of Nuclear Power Festival after Fukushima WikiLeaks and the First Amendment Introduction: Scott D. Sagan (Stanford Introduction: John A. Katzenellenbogen University) (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) Speakers: Wael Al Assad (League of Arab Speakers: Geoffrey R. Stone (University of States) and Jayantha Dhanapala (Pugwash Chicago Law School), Richard A. Posner (U.S. Conferences on Science and World Affairs) Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit), 27th Judith Miller (formerly of The New York Times), Stated Meeting–Berkeley and Gabriel Schoenfeld (Hudson Institute; Healing the Troubled American Economy Witherspoon Institute) Introduction: Robert J. Birgeneau (Univer- DECEMBER sity of California, Berkeley) 7th Speakers: Christina Romer (University of Stated Meeting–Stanford California, Berkeley) and David H. -

Carmen Tafolla

Dr. Carmen Tafolla Summary Bio: Author of more than twenty books and inducted into the Texas Institute of Letters for outstanding literary achievement, Dr. Carmen Tafolla holds a Ph.D. from the University of Texas Austin and has worked in the fields of Mexican American Studies, bilingual bicultural education, and creativity education for more than thirty- five years. The former Director of the Mexican-American Studies Center at Texas Lutheran (1973-75 and 78-79), she proceeded to pioneer the administration of cultural education projects at Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, KLRN-TV, Northern Arizona University, Scott-Foresman Publishing Company, and to be active in Latino Cultural education and community outreach for the last 35 years. An internationally noted educator, scholar and poet, Dr. Tafolla has been asked to present at colleges and universities throughout the nation, and in England, Spain, Germany, Norway, Ireland, Canada, Mexico, and New Zealand. One of the most highly anthologized of Latina writers, her work has appeared in more than 200 anthologies, magazines, journals, readers, High School American Literature textbooks, kindergarten Big Books, posters, and in the Poetry-in-Motion series installed on city buses. Her children‟s works often celebrate culture and personal empowerment. Among her awards are the Americas Award, the Charlotte Zolotow Award for best children‟s picture book writing, two Tomas Rivera Book Awards, two International Latino Book Awards, an ALA Notable Book, a Junior Library Guild Selection, the Tejas Star Listing, and the Texas 2 by 2 Award. She is the co-author of the first book ever published on Latina Civil Rights leader Emma Tenayuca, That’s Not Fair! Emma Tenayuca’s Struggle for Justice, which Críticas Magazine listed among the Best Children‟s Books of 2008. -

23Rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018 23Rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018

BASEBALL IN LITERATURE & CULTURE CONFERENCE LOGO Option 1 January 25, 2016 23rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018 23rd Annual Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference Friday, April 6, 2018 7:45 a.m. Registration and Breakfast 8:15 a.m. Welcome Andy Hazucha, Conference Coordinator Terry Haines, Ottawa University Provost 8:30 — Morning Keynote Address 9:15 a.m. Morning Keynote Speaker: Gerald Early 9:30 — Concurrent Sessions A 10:30 a.m. Session A1: Baseball in Popular Culture Location: Hasty Conference Room Chair: Shannon Dyer, Ottawa University • Eric Berg, MacMurray College: “When 1858 and 2018 Meet on the Field: Integrating the Modern Game into Vintage Base Ball” • Melissa Booker, Independent Scholar: “Baseball: The Original Social Network” • Nicholas X. Bush, Motlow State Community College: “Seams and Sestets: A Poetic Examination of Baseball Art and Culture” Session A2: Baseball History Location: Goppert Conference Room Chair: Bill Towns, Ottawa University • Mark Eberle, Fort Hays State University: “Dwight Eisenhower’s Baseball Career” • Jan Johnson, Independent Scholar: “Cartooning the Home Team” • Gerald C. Wood, Carson-Newman University: “The 1926-27 Baseball Scandal: What Happened and Why We Should Care” Session A3: From the Topps: Using Baseball Cards as Creative Inspiration (a round table discussion) Location: Zook Conference Room Chair: George Eshnaur, Ottawa University • Andrew Jones, University of Dubuque • Matt Muilenburg, University of Dubuque • Casey Pycior, University of Southern Indiana 10:45 — Concurrent Sessions B 11:45 a.m. Session B: The State of the Game (a conversation about baseball’s present and future) Location: Hasty Conference Room Chair: Greg Echlin, Kansas Public Radio and KCUR-FM • Gerald Early, Morning Keynote Speaker • Bill James, 2016 Morning Keynote Speaker • Dee Jackson, Sports Reporter for KSHB-TV, Kansas City 12:00 — Luncheon and Afternoon Keynote Speaker 1:30 p.m.