To Open the Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Law Reform with the Hon Jarrod Bleijie

The Great Leap Backward: Criminal Law Reform with the Hon Jarrod Bleijie Andrew Trotter∗ and Harry Hobbs† Abstract On 3 April 2012, the Honourable Member for Kawana, Jarrod Bleijie MP, was sworn in as Attorney-General for Queensland and Minister for Justice. In the period that followed, Queensland’s youngest Attorney-General since Sir Samuel Griffith in 1874 has implemented substantial reforms to the criminal law as part of a campaign to ‘get tough on crime’. Those reforms have been heavily and almost uniformly criticised by the profession, the judiciary and the academy. This article places the reforms in their historical context to illustrate that together they constitute a great leap backward that unravels centuries of gradual reform calculated to improve the state of human rights in criminal justice. I Introduction Human rights in the criminal law were in a fairly dire state in the Middle Ages.1 Offenders were branded with the letters of their crime to announce it to the public, until that practice was replaced in part by the large scarlet letters worn by some criminals by 1364.2 The presumption of innocence, although developed in its earliest forms in Ancient Rome, does not appear to have crystallised into a recognisable form until 1470.3 During the 16th and 17th centuries, it was common to charge the families of a prisoner sentenced to death a fee for their execution, but ∗ BA LLB (Hons) QUT; Solicitor, Doogue O’Brien George. † BA LLB (Hons) ANU; Human Rights Legal and Policy Adviser, ACT Human Rights Commission. The authors thank Professor the Hon William Gummow AC for his helpful comments on earlier drafts and the editors and anonymous reviewers for their assistance in the final stages. -

Ap2 Final 16.2.17

PALASZCZUK’S SECOND YEAR AN OVERVIEW OF 2016 ANN SCOTT HOWARD GUILLE ROGER SCOTT with cartoons by SEAN LEAHY Foreword This publication1 is the fifth in a series of Queensland political chronicles published by the TJRyan Foundation since 2012. The first two focussed on Parliament.2 They were written after the Liberal National Party had won a landslide victory and the Australian Labor Party was left with a tiny minority, led by Annastacia Palaszczuk. The third, Queensland 2014: Political Battleground,3 published in January 2015, was completed shortly before the LNP lost office in January 2015. In it we used military metaphors and the language which typified the final year of the Newman Government. The fourth, Palaszczuk’s First Year: a Political Juggling Act,4 covered the first year of the ALP minority government. The book had a cartoon by Sean Leahy on its cover which used circus metaphors to portray 2015 as a year of political balancing acts. It focussed on a single year, starting with the accession to power of the Palaszczuk Government in mid-February 2015. Given the parochial focus of our books we draw on a limited range of sources. The TJRyan Foundation website provides a repository for online sources including our own Research Reports on a range of Queensland policy areas, and papers catalogued by policy topic, as well as Queensland political history.5 A number of these reports give the historical background to the current study, particularly the anthology of contributions The Newman Years: Rise, Decline and Fall.6 Electronic links have been provided to open online sources, notably the ABC News, Brisbane Times, The Guardian, and The Conversation. -

2015 Statistical Returns

STATE GENERAL ELECTION Held on Saturday 31 January 2015 Evaluation Report and Statistical Return 2015 State General Election Evaluation Report and Statistical Return Electoral Commission of Queensland ABN: 69 195 695 244 ISBN No. 978-0-7242-6868-9 © Electoral Commission of Queensland 2015 Published by the Electoral Commission of Queensland, October 2015. The Electoral Commission of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Copyright enquiries about this publication should be directed to the Electoral Commission of Queensland, by email or in writing: EMAIL [email protected] POST GPO Box 1393, BRISBANE QLD 4001 CONTENTS Page No. Part 1: Foreword ..........................................................................................1 Part 2: Conduct of the Election ....................................................................5 Part 3: Electoral Innovation .......................................................................17 Part 4: Improvement Opportunities............................................................25 Part 5: Statistical Returns ..........................................................................31 Part 6: Ballot Paper Survey .....................................................................483 PART 1 FOREWORD 1 2 PART 1: FOREWORD Foreword The Electoral Commission of Queensland is an independent body charged with responsibility for the impartial -

Louise Rollman Thesis

CURATING THE CITY: UNPACKING CONTEMPORARY ART PRODUCTION AND SPATIAL POLITICS IN BRISBANE Louise Rollman BA (Visual Arts) (Hons), Queensland University of Technology Principal Supervisor: Professor Andrew McNamara Associate Supervisors: Dr Emma Felton External Associate Supervisor: Dr Gretchen Coombs Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Visual Arts, Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords Contemporary art; public art; commissioning for the public realm; curatorial practice; Henri Lefebvre, the right to the city and the right to imagine the city; arts policy infrastructure and institutionalization; cultural history. Curating the City: unpacking contemporary art production and spatial politics in Brisbane i Abstract Contemporary art and exhibition-making is increasingly deployed in the urban development and marketing of cities for political-economic benefit, yet the examination of the aesthetic and cultural aspects of urban life is curiously limited. In probing the unique political conditions of Brisbane, Australia, this thesis contrasts two periods — 1985-1988 and 2012-2015 — in order to more fully understand the critical pressures impacting upon the production of contemporary aesthetic projects. While drawing upon Henri Lefebvre's right to the city, and insisting upon a right to imagine the city, this thesis concludes that a consistent re-articulation of critical pressure, which anticipates oppositional positions, is necessary. Curating the City: unpacking -

The Role of Committees in Rights Protection in Federal and State Parliaments in Australia I Introduction

40 UNSW Law Journal Volume 41(1) 3 THE ROLE OF COMMITTEES IN RIGHTS PROTECTION IN FEDERAL AND STATE PARLIAMENTS IN AUSTRALIA LAURA GRENFELL* AND SARAH MOULDS** This article offers a snapshot of how Australian parliamentary committees scrutinise Bills for their rights-compliance in circumstances where the political stakes are high and the rights impacts strong. It tests the assumption that parliamentary models of rights protection are inherently flawed when it comes to Bills directed at electorally unpopular groups such as bikies and terrorists by analysing how parliamentary committees have scrutinised rights-limiting anti-bikie Bills and counter-terrorism Bills. Through these case studies a more nuanced picture emerges, with evidence that, in the right circumstances, parliamentary scrutiny of ‘law and order’ can have a discernible rights-enhancing impact. The article argues that when parliamentary committees engage external stakeholders they can contribute to the development of an emerging culture of rights-scrutiny. While this emerging culture may not yet work to prevent serious intrusions into individual rights, at the federal level there are signs it may at least be capable of moderating these intrusions. I INTRODUCTION Australia has a parliamentary model of rights protection which means that, outside of the protections provided by the Constitution and the common law, most Parliaments in Australia have almost exclusive responsibility for directly protecting the rights of all members of the community. Only in two Australian Parliaments, those of Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory, is this direct * Dr Laura Grenfell is an Associate Professor at the University of Adelaide Law School where she teaches and researches public law and human rights. -

China an Opportunity for Local Businesses

2/10/2019 China an opportunity for local businesses OPPORTUNITY awaits Hinchinbrook businesses in China if they are willing to put the time and effort in to forging strong trade ties, says Hinchinbrook MP Nick Dametto. Speaking after a week-long visit to Shanghai as part of a parliamentary trade delegation, Mr Dametto said there was an “extraordinary” demand for high quality, premium products from Australia in which local businesses could potentially capitalise on. “Instead of selling out to Chinese investors, there is a real opportunity to produce here and partner with Chinese import/distribution companies to fully capitalise on this growing market,” he said. “But you have to be ready to invest in building relationships with the Chinese. Spend your time carefully picking the right business to partner with, and be willing to invest significantly in marketing and packaging and most of all, be ready to supply your product if it takes off. “Although difficult, it’s not impossible to crack the market and is very rewarding with a middle class of an estimated 400 million people. To throw some figures around this, it is said if your new business or product launch isn’t seeing triple figure growth in the first four to five years, that can be interpreted as a floundering or failing product.” Mr Dametto met with representatives from Austrade, Trade and Investment Queensland (TIQ) and multinational e-commerce business Alibaba during his trip, which marked 30 years of the sister-state relationship between Queensland and Shanghai. “Those discussions made it clear to me that the Chinese do not appreciate foreigners who view them as a modern day cash cow and you will have far more success if you treat them as a friend,” he said. -

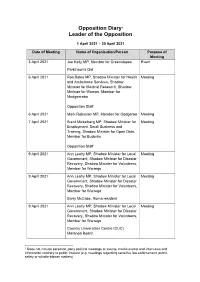

Extracts from the Leader of the Opposition Diary

Opposition Diary1 Leader of the Opposition 1 April 2021 – 30 April 2021 Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting 3 April 2021 Joe Kelly MP, Member for Greenslopes Event Parkinson’s Qld 6 April 2021 Ros Bates MP, Shadow Minister for Health Meeting and Ambulance Services, Shadow Minister for Medical Research, Shadow Minister for Women, Member for Mudgeeraba Opposition Staff 6 April 2021 Mark Robinson MP, Member for Oodgeroo Meeting 7 April 2021 Brent Mickelberg MP, Shadow Minister for Meeting Employment, Small Business and Training, Shadow Minister for Open Data, Member for Buderim Opposition Staff 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow Minister for Disaster Recovery, Shadow Minister for Volunteers, Member for Warrego 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow Minister for Disaster Recovery, Shadow Minister for Volunteers, Member for Warrego Barry McCabe, Roma resident 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow Minister for Disaster Recovery, Shadow Minister for Volunteers, Member for Warrego Country Universities Centre (CUC) Maranoa Board 1 Does not include personal, party political meetings or events, media events and interviews and information contrary to public interest (e.g. meetings regarding sensitive law enforcement, public safety or whistle-blower matters) Date of Meeting Name of Organisation/Person Purpose of Meeting 9 April 2021 Ann Leahy MP, Shadow Minister for Local Meeting Government, Shadow -

Jarrod Bleijiemp

Jarrod BLEIJIEmp Member for Kawana Shadow Minister for Education and Shadow Minister for Industrial Relations Manager of Opposition Business 25 October 2019 Queensland Legislative Assembly Number:_ ■ -k . Hon. Curtis Pitt MP Tabled O' Speaker of the Legislative Assembly By Leave By email: [email protected] Clerk's Signature: Dear Mr Sp I ask you to investigate a discussion using unparliamentary language during consideration in detail of the Summary Offences and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2019. As has been reported in the media, the Chamber Broadcast at 4:15 - 4:17 on Thursday 24 October 2019 records a male voice using unparliamentary language in relation to a woman. Based on the audio the language used was: “She's a f***wit.... I think she’s on something.” The use of such language in reference to a female Member of Parliament is highly disorderly and could amount to a breach of the Ethical Standards of the Parliament and the Standing Orders. On my review of the Chamber audio and visual, I formed the view that It was the Member for Toohey, Mr Peter Russo MP who made the remarks. He can be seen leaning towards the Member for Aspley, Mr Bart Mellish when the comment is made. Immediately following the last comment, the Member for Macalister reaches over, apparently to switch off the live microphone. It has nearly been 24 hours since the comment was made. I note that the Member for Toohey has just uploaded the following apology to his facebook site. *7 apologise to Parliament for my unparliamentary language that was recorded in the House during a division yesterday. -

1 Queensland 57Th Parliament 2020-2024 Information Taken From

1 Queensland 57th Parliament 2020-2024 Information taken from: https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/members/current See also: the Ministerial Charter Letters (MCL) outlining the Government’s priorities, that each Minister (and Assistant Minister) is responsible for delivering over this term of government, were uploaded to the QLD Government website on 1 December 2020. The Ministerial Charter Letters’ also include the election commitments that each Minister (and Assistant Minister) is responsible for delivering. Link: https://cabinet.qld.gov.au/ministers/charter-letters.aspx Ministerial Portfolios Shadow Minister Portfolios Name & Address Email & Phone ALP Name & Address Email & Phone LNP Portfolio Electorate Portfolio Electorate Hon PO Box Phone: 3719 7000 Inala Mr David PO Box Phone: (07) 3838 6767 Broadwater Annastacia 15185, Crisafulli 15057 Palasczuk City East Email: Leader of the CITY EAST Email: Premier & Qld 4002 [email protected] Opposition & QLD 4002 [email protected] Minister for u Shadow Minister for Tourism Trade Mr David Janetzki [email protected] Shadow Minister for Investment and Trade Hon Dr Steven PO Box Phone: (07) 3719 7100 Murrumba Mr David Janetzki PO Box Phone: (07) 5351 6100 Lockyer Miles 15009 Fax: n/a Deputy Leader of 3005 Fax: n/a Deputy CITY EAST Email: the Opposition, TOOWOOM Email: Premier and QLD 4002 deputy.premier@Bleijieministeri Ms Fiona BA QLD [email protected] Minister for al.qld.gov.au Simpson Shadow 4350 State Minister for State Development, Development -

ETHICS COMMITTEE Report No. 121 Matter of Privilege Referred by The

ETHICS COMMITTEE Report No. 121 Matter of privilege referred by the Speaker on 27 October 2011 relating to an alleged deliberate misleading of the House by a minister Introduction and background 1. The Ethics Committee (the committee) is a statutory committee of the Queensland Parliament established under section 102 of the Parliament of Queensland Act 2001 (the POQA or the Act). The current committee was appointed by resolution of the Legislative Assembly on 16 June 2011. 2. The committee’s area of responsibility includes dealing with complaints about the ethical conduct of particular members and dealing with alleged breaches of parliamentary privilege by members of the Assembly and other persons.1 The committee investigates and reports on matters of privilege and possible contempts of parliament referred to it by the Speaker or the House. 3. The matter in this report concerns an allegation by the member for Kawana, Mr Jarrod Bleijie, that the Minister for Education and Industrial Relations, Hon Cameron Dick deliberately misled the House on 2 August 2011. 4. In accordance with Standing Order 269, the member for Kawana wrote to the Speaker on 29 August 2011, asking that the Speaker refer the matter to the committee. 5. Standing Order 269(5) provides that, in relation to the procedures for raising and considering complaints, the Speaker may request information from the member the subject of the complaint. Accordingly, the Speaker sought further information from the minister regarding the member’s complaint. The Speaker subsequently received a submission from the minister on 26 September 2011. 6. On 27 October 2011, after examining the information before him, the Speaker referred the matter to the committee for its consideration. -

Estimates Committee Transcript

9 Dec 2020 Estimates—Education, Industrial Relations and Racing 1 WEDNESDAY, 9 DECEMBER 2020 _______________ ESTIMATES—EDUCATION, EMPLOYMENT AND TRAINING COMMITTEE— EDUCATION, INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS AND RACING EST IMATES—EDUCATION, INDUSTRIAL R EL ATI ONS AN D R ACING Estimate Committee Members Ms KE Richards (Chair) Mr JP Lister Mr MA Boothman Mr N Dametto Mr BL O’Rourke Mr JA Sullivan _______________ Members in Attendance Dr CAC Rowan Dr A MacMahon Ms FS Simpson Mr SSJ Andrew Mr MC Berkman Mr TL Mander Mr JP Bleijie Mr BA Mickelberg _______________ In Attendance Hon. G Grace, Minister for Education, Minister for Industrial Relations and Minister for Racing Ms S Durham, Chief of Staff Department of Education Mr T Cook, Director-General Mr D Anson, Deputy Director, General, Corporate Services Office of Industrial Relations Mr C Allen, Deputy Director-General Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Dr E Woods, Director-General _______________ The committee met at 9.00 am. CHAIR: Good morning. I declare this hearing of estimates for the Education, Employment and Training Committee open. I acknowledge that we are meeting on custodial land of the oldest living civilisation in the world. I pay my respects to both the Jagera people and the Turrbal people and their elders, past, present and emerging. 2 Estimates—Education, Industrial Relations and Racing 9 Dec 2020 I am Kim Richards, the member for Redlands and chair of the committee. Mr James Lister, the member for Southern Downs, is the deputy chair. The other members of the committee are: Mr Mark Boothman, the member for Theodore; Mr Nick Dametto, the member for Hinchinbrook; Mr Barry O’Rourke, the member for Rockhampton; and Mr Jimmy Sullivan, the member for Stafford. -

2012 Statistical Returns

2012 EVALUATION REPORT AND STATISTICAL RETURNS ELECTORAL COMMISSION QUEENSLAND QUEENSLAND ELECTION 24 March SOUTH BRISBANE BY-ELECTION 28 April 2012 State General Election: Evaluation Report and Statistical Returns QUEENSLAND STATE ELECTION 2012 Held on SATURDAY 24 MARCH 2012 EVALUATION REPORT AND STATISTICAL RETURNS ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF QUEENSLAND Electoral Commission of Queensland GPO Box 1393 BRISBANE QLD 4001 Telephone: 1300 881 665 Fax: (07) 3229 7391 Email: [email protected] © Electoral Commission Queensland 1 2012 State General Election: Evaluation Report and Statistical Returns Queensland State General Election 2012 Statistical Returns Electoral Commission of Queensland ABN: 69 195 695 244 ISBN No. 978-0-7242-6868-9 November 2012 2 © Electoral Commission Queensland 2012 State General Election: Evaluation Report and Statistical Returns CONTENTS Page No Letter to the Attorney-General and Minister for Justice ......................................... 5 Part 1: Foreword ...................................................................................................... 9 Part 2: Conduct of the Election ............................................................................... 13 Part 3: Client Feedback ........................................................................................... 21 Part 4: Electoral Innovation ..................................................................................... 29 Part 5: Where Can We Improve? ............................................................................ 33