The Development of Nursing As a Profession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nursing 1 Nursing

Nursing 1 Nursing For other uses, see Nursing (disambiguation). "Nurse" redirects here. For other uses, see Nurse (disambiguation). Nurse A British nurse caring for a baby in 2006 Occupation Names Nurse Occupation type Healthcare professional Activity sectors Nursing, Health care Description Competencies Caring for general well-being of patients Education required Qualifications in terms of statutory regulations according to national, state, or provincial legislation in each country Nursing is a profession within the health care sector focused on the care of individuals, families, and communities so they may attain, maintain, or recover optimal health and quality of life. Nurses may be differentiated from other health care providers by their approach to patient care, training, and scope of practice. Nurses practice in a wide diversity of practice areas with a different scope of practice and level of prescriber authority in each. Many nurses provide care within the ordering scope of physicians, and this traditional role has come to shape the historic public image of nurses as care providers. However, nurses are permitted by most jurisdictions to practice independently in a variety of settings depending on training level. In the postwar period, nurse education has undergone a process of diversification towards advanced and specialized credentials, and many of the traditional regulations and provider roles are changing. Nurses develop a plan of care, working collaboratively with physicians, therapists, the patient, the patient's family and other team members, that focuses on treating illness to improve quality of life. In the U.S. (and increasingly the United Kingdom), advanced practice nurses, such as clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners, diagnose health problems and prescribe medications and other therapies, depending on individual state regulations. -

Facts About the Shortage of Nurses in Virginia

Facts about the Shortage of Nurses in Virginia By 2020, one in three Virginians will not receive the health care needed because of the shortage of registered nurses. • The demand for full-time equivalent nurses will be 69,600 and the actual number of employed nurses will remain relatively constant at 47,0001. This is a 32% shortfall. Nurses Save Lives • Researchers estimated that, for every 1,000 hospital patients, an increase of one full-time RN per day could save five lives in ICUs, five lives on medical floors and six lives in surgical units. • Furthermore, the researchers determined that staffing one additional RN per day was associated with lower rates of hospital-acquired pneumonia, respiratory failure and cardiac arrest among ICU patients. Such an increase also could reduce hospital length of stay in ICUs and surgical units by as much as 34 percent and 31 percent, respectively." 2 Each year, the Virginia Board of Nursing licenses fewer than 2,000 newly graduated RNs from Virginia Schools of Nursing • Beginning in 2015, it is forecasted the number of retiring RNs will exceed the number of new RN graduates entering the workforce. Statewide, Schools of Nursing report a total enrollment of about 6,000 students educated in public and private colleges and universities and in hospital settings. • Nationally, three qualified applicants are denied admission for every student applicant accepted because of inadequate capacity in the schools. There is every reason to believe Virginia statistics are comparable. Increasing educational capacity requires more academically qualified faculty. • Currently, faculty salaries for nurse educators are not competitive with salaries of nurses in non-academic positions and settings3. -

Nursing's Future Comes to Life in Driscoll Hall

SPRING/ SUMMER 2 0 0 9 A PUBLICATION OF THE VILLANOVA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF NURSING Nursing’s Future Comes to Life in Driscoll Hall College of Nursing Board of Consultors gueras NO la O • H.E. Dr. Ali Al-Moosa A P • Mr. Thomas E. Beeman • Rear Adm. Christine M. Bruzek-Kohler • Dr. Helen R. Connors • Mrs. Tara M. Easter • Rear Adm. (Ret.) James W. Eastwood • Mr. Stephen P. Fera • Mr. Daniel Finnegan • Dr. M. Louise Fitzpatrick, Ex officio • Ms. Margaret M. Hannan • Veronica Hill-Milbourne, Esq. • Mr. Richard J. Kreider • Mr. J. Patrick Lupton • Dr. Thomas F. Monahan • Dr. Mary D. Naylor • Mr. James V. O’Donnell Mrs. Sue Stein, staff Mark your calendar! October 4 Undergraduate Open House November 16 Annual Distinguished Lecture Dr. Mary D. Naylor ’71 B.S.N., Ph.D., R.N., FAAN, the Marian S. Ware In the lobby of Driscoll Hall, the Crucifix, designed and painted in the Byzantine style by Professor in Gerontology and director Edward Ruscil, includes depictions of the Visita- of the Center for Health Transitions, tion and the parable of the Good Samaritan. School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania Villanova Nursing Vol. 28 No. 1 Spring/Summer 2009 Features On the Cover: In May, the Class of 2009 became the first B.S.N. class Driscoll Hall Advances Nursing’s Future ........................2 to graduate from the College of Nursing following the opening of Driscoll Hall last fall. Thank You to the Donors .........................................11 Editorial Board College Launches Campaign Ann Barrow McKenzie ’86 B.S.N., ’91 M.S.N., R.N., Editor Promoting Nursing ....................... -

Strategies to Overcome the Nursing Shortage Edward A

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2017 Strategies to Overcome the Nursing Shortage Edward A. Mehdaova Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Health and Medical Administration Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Edward Mehdaova has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Mohamad Hammoud, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Michael Campo, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Roger Mayer, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2017 Abstract Strategies to Overcome the Nursing Shortage by Edward Mehdaova MBA, Indiana Wesleyan University, 2012 BSBA, Indiana Wesleyan University, 2009 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University December 2017 Abstract Nursing shortage is a growing problem in the healthcare industry as hospital leaders are experiencing difficulties recruiting and retaining nurses. Guided by the PESTEL framework theory, the purpose of this case study was to explore strategies healthcare leaders use to overcome a nursing shortage. -

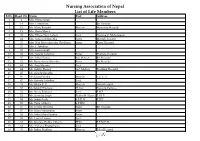

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Who We Are Dean’S Welcome

WHO WE ARE DEAN’S WELCOME Dear friends, This month I took part in my fifth year of graduation and commencement ceremonies at NYU as dean. What an excit- ing time! To see students work so hard and then finally walk across the stage to receive their diplomas, and, for many, enter a new stage in their lives, is the highlight of my year. We have prepared our recent graduates to become leaders at a critical moment in healthcare—a time to reimagine how best to deliver high-quality, affordable care. As nurses, we are uniquely positioned to develop and implement the inno- vation required to tackle this challenge, and more broadly, the world’s most pressing issues like poverty, mental health, climate change, chronic illness, substance abuse, and the effects of an aging population. We know our new graduates—the extraordinary class of 2017—will rise to the challenge. I hope you will join me in saluting them. In the spring issue of NYU Nursing, we are proud to STATEMENT ON DIVERSITY showcase who we are and you will: AND INCLUSION • Explore the US-China relationship and the two countries’ WELCOME. shared healthcare challenges; NEW YORK UNIVERSITY RORY MEYERS COLLEGE • OF NURSING is committed to the inclusion and Meet Assistant Professor Yzette Lanier, a developmental support of individuals and ideas from all who psychologist studying HIV behavioral intervention; comprise our multicultural community. The College embraces the richness of diversity in its • Discover how first-generation college students integrate multiple dimensions that exist within and around into the classroom and campus life; us, including: race, ethnicity, nationality, class, sex, gender identity/expression, ability, faith/belief, • Experience what it’s like for a male nurse midwife, sexual orientation, and age. -

Nursing and Allied Health Shortages: TBR Responds. INSTITUTION Tennessee State Board of Regents, Nashville

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 709 CE 085 492 AUTHOR Berryman, Treva TITLE Nursing and Allied Health Shortages: TBR Responds. INSTITUTION Tennessee State Board of Regents, Nashville. PUB DATE 2002-12-00 NOTE 12p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.tbr.state.tn.us/academic_affairs/ news/nrsah.htm. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Allied Health Occupations; Allied Health Occupations Education; Demand Occupations; Education Work Relationship; Educational Finance; Educational Planning; Employment Patterns; *Labor Needs; Labor Turnover; Nurses; *Nursing; *Nursing Education; *Policy Formation; Postsecondary Education; *Public Policy; Role of Education; Secondary Education; Statewide Planning; Student Financial Aid; *Student Recruitment IDENTIFIERS Health Personnel Shortage; Nursing Shortage; *Tennessee ABSTRACT Staff members of the Tennessee Board of Regents (TBR) and the Tennessee Higher Education Commission worked jointly to establish a task force to investigate and develop recommendations for addressing the workforce shortages in nursing and allied health in Tennessee. The investigation established that Tennessee already has a workforce shortage of health care professionals, especially registered nurses, and that the shortage will become critical over the next 10 to 15 years. The task force recommended that TBR institutions apply for the federal grants available through the Nursing Reinvestment Act. The following are among the eight recommendations addressed -

Lawrlwytho'r Atodiad Gwreiddiol

Operational services structure April 2021 14/04/2021 Operational Leadership Structures Director of Operations Director of Nursing & Quality Medical Director Lee McMenamy Joanne Hiley Dr Tessa Myatt Medical Operations Operations Clinical Director of Operations Deputy Director of Nursing & Deputy Medical Director Hazel Hendriksen Governance Dr Jose Mathew Assistant Clinical Director Assistant Director of Assistant Clinical DWiraerctringor ton & Halton Operations Corporate Corporate Lorna Pink Assistant Assistant Director Julie Chadwick Vacant Clinical Director of Nursing, AHP & Associate Clinical Director Governance & Professional Warrington & Halton Compliance Standards Assistant Director of Operations Assistant Clinical Director Dr Aravind Komuravelli Halton & Warrington Knowsley Lee Bloomfield Claire Hammill Clare Dooley Berni Fay-Dunkley Assistant Director of Operations Knowsley Associate Medical Director Nicky Over Assistant Clinical Director Allied Health Knowsley Assistant Director of Sefton Professional Dr Ashish Kumar AssiOstapenrta Dtiironesc tKnor oofw Oslpeeyr ations Sara Harrison Lead Nicola Over Sefton James Hester Anne Tattersall Assistant Clinical Director Associate Clinical Director Assistant Director of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients St Helens Operations Sefton Debbie Tubey Dr Raj Madgula AssistanAt nDniree Tcatttore ofrs aOllp erations Head of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients Safeguarding Tim McPhee Assistant Clinical Director Sarah Shaw Assistant Director of Associate Medical Director Operations St Helens Mental Health -

The Nursing Shortage

THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT / THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK / ALBANY, NY 12234 TO: The Honorable the Members of the Board of Regents FROM: Johanna Duncan-Poitier COMMITTEE: Full Board TITLE: The Nursing Shortage DATE OF SUBMISSION: April 16, 2001 PROPOSED HANDLING: Discussion RATIONALE FOR ITEM: To inform the Regents about an emerging public protection issue and gain support of recommended actions STRATEGIC GOAL: Goal 3 AUTHORIZATION(S): EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is the eighth in a series of reports to the Board of Regents on emerging issues in professional regulation. The report deals with a potential crisis that may seriously affect all New Yorkers in the next few years – the nursing shortage. Previous reports in this series include corporate practice of the professions, telepractice, cross- jurisdictional professional practice, continuing competence, effective professional regulation and discipline, illegal (unlicensed) practice of the professions, and rising consumer expectations. This report describes a fundamental health care issue that is basic to the Regents public protection mission. The critical shortage of qualified nurses projected within the next five years will have a profound effect on health care for New York’s consumers well into this new century. Failure to successfully address the problem will threaten the quality and safety of the entire health care system in this State, the welfare of consumers who depend on this system for patient care, and the future of the professionals who practice within this system. Research points to a nursing shortage that, if unaddressed, will be more severe and longer in duration than those previously experienced in New York. -

The Nursing Alumni Association at 20 Years Page 2

learning the hbrighamealer’s young university college of nursin artg Fall 2019 The Nursing Alumni Association at 20 Years Page 2 Night of Nursing Expansion Page 8 New Faculty Page 20 Dean’s Message learning the Fall 2019 The Family Connection: It’s All Relative healer’s art I recently read an entry from urban- the college alumni association supports Just as your own family dictionary.com that defined family as activities to enhance student learning, a group of people “who genuinely love, foster employment for graduates, and can provide strength trust, care about, and look out for each create collegial relationships that build other. Real family is a bondage that the individual, the profession, and the . the college alumni cannot be broken by any means.” reputation of Brigham Young University. That got me thinking about the “fami- A sense of belonging supports the mis- association supports lies” we have here at the College of Nursing. sion and goals of the college by rekindling activities to enhance In each of the six nursing semesters, the spirit of the BYU nursing experience, individuals sustain one another as they encouraging financial contributions, pro- student learning, advanced together through the program moting a sense of community, and har- for three years. They learn to value mem- monizing nursing with gospel principles foster employment for 2 8 20 bers for their unique abilities and assets, through knowledge, faith, and healing. rather than as competition; spending This issue features stories of ways to graduates, and create hours as one group establishes our car- connect with the college alumni asso- collegial relationships ing heritage. -

Search Titles and Presenters at Past AAHN Conferences from 1984

American Association for the History of Nursing, Inc. 10200 W. 44th Avenue, Suite 304 Wheat Ridge, CO 80033 Phone: (303) 422-2685 Fax: (303) 422-8894 [email protected] www.aahn.org Titles and Presenters at Past AAHN Conferences 1984 – 2010 Papers remain the intellectual property of the researchers and are not available through the AAHN. 2010 Co-sponsor: Royal Holloway, University of London, England September 14 - 16, 2010 London, England Photo Album Conference Podcasts The following podcasts are available for download by right-clicking on the talk required and selecting "Save target/link as ..." Fiona Ross: Conference Welcome [28Mb-28m31s] Mark Bostridge: A Florence Nightingale for the 21st Century [51Mb-53m29s] Lynn McDonald: The Nightingale system of training and its influence worldwide [13Mb-13m34s] Carol Helmstadter: Nightingale Training in Context [15Mb-16m42s] Judith Godden: The Power of the Ideal: How the Nightingale System shaped modern nursing [17Mb-18m14s] Barbra Mann-Wall: Nuns, Nightingale and Nursing [15Mb-15m36s] Dr Afaf Meleis: Nursing Connections Past and Present: A Global Perspective [58Mb-61m00s] 2009 Co-sponsor: School of Nursing, University of Minnesota September 24 - 27, 2009 Minneapolis, Minnesota Paper Presentations Protecting and Healing the Physical Wound: Control of Wound Infection in the First World War Christine Hallett ―A Silent but Serious Struggle Against the Sisters‖: Working-Class German Men in Nursing, 1903- 1934 Aeleah Soine, PhDc The Ties that Bind: Tale of Urban Health Work in Philadelphia‘s Black Belt, 1912-1922 J. Margo Brooks Carthon, PhD, RN, APN-BC The Cow Question: Solving the TB Problem in Chicago, 1903-1920 Wendy Burgess, PhD, RN ―Pioneers In Preventative Health‖: The Work of The Chicago Mts. -

Nursing Documentation in Clinical Practice

From the Department of Nursing, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Nursing Documentation in Clinical Practice Instrument development and evaluation of a comprehensive intervention programme Catrin Björvell Stockholm 2002 Nursing Documentation in Clinical Practice Instrument development and effects of a comprehensive education programme By: Catrin Björvell Cover layout: Tommy Säflund Printed at: ReproPrint AB, Stockholm ISBN 91-7349-297-3 NURSING DOCUMENTATION IN CLINICAL PRACTICE There is nothing more difficult to carry out, nor more doubtful of success, nor more dangerous to handle than to initiate a new order of thing. Machiavelli, The Prince Nursing documentation in clinical practice Instrument development and evaluation of a comprehensive intervention programme Catrin Björvell, Department of Nursing, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Abstract The purpose of this study was to describe and analyse effects of a two-year comprehensive intervention concerning nursing documentation in patient records when using the VIPS model - a model designed to structure nursing documentation. Registered Nurses (RNs) from three acute care hospital wards participated in a two-year intervention programme, in addition, a fourth ward was used for comparison. The intervention consisted of education about nursing documentation in accordance with the VIPS model and organisational changes. To evaluate effects of the intervention patient records (n=269) were audited on three occasions: before the intervention, immediately after the intervention and three years after the intervention. For this purpose, a patient record audit instrument, the Cat-ch-Ing, was constructed and tested. The instrument aims at measuring both quantitatively and qualitatively to what extent the content of the nursing process is documented in the patient record.